Economies prior to the late 20th Century

The Indian Act (1876), literally “An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Laws Respecting Indians” is still in use today, though it is shrinking steadily as sections are repealed. This Act is the default document regulating First Nation reserves.

Because of this Act and other early legislation, “Indian” is a word with legal meaning. Being “Indian” in the sense of the Indian Act means being a person of Indigenous heritage to whom the government has a fiduciary duty, a duty to act in their best interests.

Though Inuit and Métis people are legally “Indian” in this sense, the Indian Act has not been applied to them. First Nations who have negotiated modern treaties do not have it applied to them either. First Nations who have pre-modern treaties are under the Indian Act, but have the option of replacing parts of it with alternative legislation such as the First Nations Land Management Act (1999) and the First Nations Elections Act (2015).

Summary of the Indian Act

There are 3 main things to know about the Indian Act:

- The Indian Act does not outline the government’s obligations to First Nations. Obligations toward First Nations, arising from the Treaties, are not set forth in the Indian Act or anywhere else.

- The Indian Act pertains only to First Nations people who have Registered or Treaty Indian Status. Status Indians are descendants of First Nations who signed Treaties or who became members of reserve communities, if they meet certain criteria related to having married only other Status Indians. We will discuss these criteria in our next chapter. The government keeps the Indian Register, a list of Status Indians.

- In a nutshell, the Indian Act protects the reserve land base (in writing, if not in actuality), and authorizes the federal government to manage any money that might be earned from the reserve or that might otherwise accrue to the Band. Its regulations concern fair distribution of land use revenues among Band members, inheritances of Band members, democratic representation of Status Indians at the Band level, and maintaining good living conditions on reserve. It has also restricted some activities (e.g. legal actions, sales of alcohol) and mandated others (e.g. attendance of children at residential schools).

The bottom line is this:

“In the event of any conflict between any regulation made by the Superintendent General and any rule or regulation made by any band, the regulations made by the Superintendent General shall prevail.” (1914 Ch. 35 s. 6).

What the Indian Act says about reserve lands

The Indian Act protects reserve lands and their minerals, trees and wildlife from trespassing and exploitation. In 1906 a provision was added forbidding anyone from taking totem poles and other art works from a reserve without the written consent of the government.

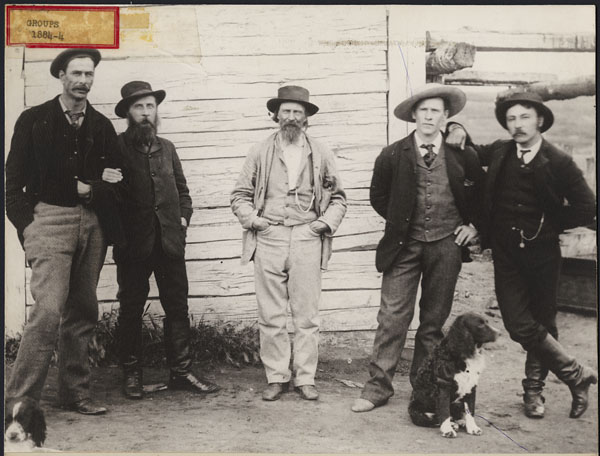

This was critical because many First Nations’ reserves, such as the Mohawks’ in Tyendinaga, had shrunk considerably though unscrupulous contracts made without the oversight of representatives of the Crown. Even after the Indian Act was passed, reserves in mainland British Columbia shrank drastically as settlers encroached.

Between 1911-1951 an amendment to the Indian Act allowed municipal governments to evict First Nations from reserves which were in towns and cities, that is to say, premium locations. Thus Squamish Nation was evicted from their reserve in what is now downtown Vancouver.

Four years before this amendment became law, Peguis First Nation, a signatory of Treaty 1, had been enticed by the government to leave their prime location near present-day Winnipeg for a larger piece of land 190 km north. In 1998 Canada admitted it had violated the Indian Act and agreed to compensate the Peguis $126 million. Peguis has since acquired two reserves in Winnipeg. (See Chapter 25 for more on urban reserves.)

Typically, the Indian Act protected reserves from encroachment by ordinary people, but not from encroachment by government.

The Indian Act specifies ways to grant individual members portions of land for their own use. (More on this in Chapter 24.) It protects reserve lands, and the assets of Status persons living on reserves, from seizure by creditors, and from federal or provincial taxation. It also has clauses to protect the inheritances of widows and orphans.

To avoid conflict of interest, missionaries, educators, and government agents are prohibited from doing business with First Nations unless they have written permission from the government.

In 1886 the Act’s Section 2 declares that the reserve includes all the trees, wood, timber, soil, stone, subsurface minerals, metals and other valuables thereon or therein. However, other legislation has made it clear that no removal of timber (or other resources, presumably) can be done without a license from the government.

In 1938 a revolving loan fund was set up for First Nations individuals, groups, or bands for agriculture, fishing, handicrafts or other ventures. The money comes from federal tax revenues.

What the Indian Act says about money earned using reserve land

In 2017 there are still provisions such as section 61:

61. (1) Indian moneys shall be expended only for the benefit of the Indians or bands for whose use and benefit in common the moneys are received or held, and subject to this Act and to the terms of any treaty or surrender, the Governor in Council may determine whether any purpose for which Indian moneys are used or are to be used is for the use and benefit of the band.

61. (2) Interest on Indian moneys held in the Consolidated Revenue Fund shall be allowed at a rate to be fixed from time to time by the Governor in Council.

What is this Consolidated Revenue Fund?

The Consolidated Revenue Fund, more commonly known as the Indian Moneys Trust Fund, is a federal government bank account into which First Nations’ money has been deposited since 1858. As described in several Yellowhead Institute publications, such as Pasternak (2021), any earnings from reserve land leased or sold, and any earnings from natural resources owned by the Band, are deposited in this fund. Reparations owed to the Band for violations of past treaty promises are also typically deposited into this fund.

As of 2019 the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte in Tyendinaga, Ontario were receiving a yearly payment from Enbridge Inc. for a gas pipeline that runs through land that once belonged to their reserve. This money was going directly to the Indian Moneys Trust Fund. The Band had to request access to the money.

One billion dollars was parked in this fund for about twenty-five years, beginning during the 1980s. It was earning interest at the low rate applicable to ten-year Canadian government bonds.

At times, some of the Trust money has been lent to non-Indigenous people by the federal government, and has never been returned.

In 1918 the government gave itself the right to spend the band’s money on any construction, land, cattle, or machinery deemed to be in the band’s interests, even if the band does not consent. This was eventually repealed.

In 1918 the government gave itself the right to spend the band’s money on any construction, land, cattle, or machinery deemed to be in the band’s interests, even if the band does not consent. This was eventually repealed.

In 1918 the government gave itself the right to lease out unused agricultural land on reserves, or hire people to cultivate those lands, without the consent of the band, and to spend band money on improvements to that land or on inputs used to cultivate that land. By 2002 this was softened to “with the consent of the Band”.

In 1919, section 141 allowed the government to reduce the rent on leased reserve land, or reduce the price charged or interest collected on the sale of lands. Eventually softened to “with the consent of the band”.

What the Indian Act has said about the economic activity of individuals living on reserve

In 1876 Status or non-Status Indians were forbidden to acquire a new homestead on the western frontier.

In 1881, chapter 17 sections 1-3, the Governor in Council was permitted to prohibit or regulate sales of “grain or root crops, or other produce grown upon any Indian Reserve” in Manitoba and beyond. These prohibitions were explicitly applied to Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1906.

(1) The Governor in Council may make such provisions and regulations as may, from time to time, seem advisable for prohibiting or regulating the sale, barter, exchange or gift, by any band or irregular band of Indians, or by any Indian of any band or irregular band, in the North-West Territories, the Province of Manitoba, or the District of Keewatin, of any grain or root crops, or other produce grown upon any Indian Reserve…

(2) Any person who buys or otherwise acquires from any such Indian, or band, or irregular band of Indians, contrary to any provisions or regulation made by the Governor in Council under this Act, is guilty of an offence, and is punishable, upon summary conviction, by fine, not exceeding one hundred dollars, or by imprisonment for a period not exceeding three months, in any place of confinement other than a penitentiary, or by both fine and imprisonment.

Also in 1886, no non-band member was allowed on reserve to trade or barter goods unless licensed by the government. The government could apply provincial hunting regulations to Indians.

In 1930 the agricultural trade prohibitions were still in force and had been expanded to include livestock.

In 1940 Indians, whether Status or not, were prohibited from selling wild animals or parts of wild animals, presumably including meat and hides.

In 1951 the trade restrictions were limited to the Prairie Provinces:

32. (1) A transaction of any kind whereby a band or a member thereof purports to sell, barter, exchange, give or otherwise dispose of cattle or other animals, grain or hay, whether wild or cultivated, or root crops or plants or their products from a reserve in Manitoba, Saskatchewan or Alberta, to a person other than a member of that band, is void unless the superintendent approves the transaction in writing.

32. (2) The Minister may at any time by order exempt a band and the members thereof or any member thereof from the operation of this section and may revoke any such order.

These restrictions were gradually loosened and repealed, but the restriction on agricultural sales was not removed from the Indian Act until 2014.

Other impositions of the Indian Act

In 1881 the Indian Act proclaimed every Indian Commissioner, Assistant Indian Commissioner, Indian Superintendent, Indian Inspector or Indian Agent a Justice of the Peace for the purposes of carrying out the regulations in the Indian Act.

In 1884 the Act specified that any group of three or more First Nations or Métis who make requests or demands to officials in a disorderly or threatening manner be liable to two years imprisonment with or without hard labour.

1884 It gave the government authority to prohibit the sale or gift of ammunition to First Nations.

1884 Indian men became automatically enfranchised upon receiving a university degree, or becoming a minister or lawyer. That means that they lose their Indian Status, whether they want to or not. Wife and minor children also lose their Status. We will discuss enfranchisement more in Chapter 11.

1884 “Any Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the “Potlatch” or in the Indian dance known as the “Tamanawas” is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than six nor less than two months…” This and other cultural laws were removed in 1951.

In 1927 “Any Indian [in the West or Northwest] who participates in any Indian dance outside the bounds of his own reserve, or who participates in any show, exhibition, performance, stampede or pageant in aboriginal costume without the consent of the Superintendent General or his authorized agent…shall on summary conviction be liable to a penalty not exceeding twenty-five dollars, or to imprisonment for one month, or to both penalty and imprisonment.” This rule was still in the Act in 1970.

The 1886 edition removed band membership from any member who leaves Canada for more than five years without the permission of the government.

From 1881 on, Status Indians had the right to sue for debts owed to them, but in 1927 Section 141 of the Indian Act was added, forbidding First Nations to pay or reimburse anyone for postage, travel, research, legal fees, or court costs.[1]

In 1886 the Indian Act permitted the government to compel school attendance at a school of the government’s choice.

138. The Governor in Council may establish an industrial school or a boarding school for Indians, or may declare any existing Indian school to be such industrial school or boarding school for the purposes of this section.

138. (2) The Governor in Council may make regulations, which shall have the force of law, for the committal by justices or Indian agents of children of Indian blood under the age of sixteen years, to such industrial school or boarding school, there to be kept, cared for and educated for a period not extending beyond the time at which such children shall reach the age of eighteen years.

Section 138 also gave the government permission to fund the school with annuity payments or interest on moneys held in trust for the children. Later this money had to be used specifically for maintenance of the children at the school.

Section 137 spoke of fines and imprisonment for parents and guardians who do not cause their children to attend school. Later versions of the Indian Act gave truant officers the right to compel attendance. In 2013 this was still in the Act:

119. (6) A truant officer may take into custody a child whom he believes on reasonable grounds to be absent from school contrary to this Act and may convey the child to school, using as much force as the circumstances require.

Ultimately, the Indian Act was amended in 2014 to end the government’s involvement with religious schools, prevent the government from using a child’s trust money for school fees, allow youth over 16 years of age to drop-out of school, and prevent the government from coercing students into attending school.

The Future of the Indian Act

Recall, from the prelude to this textbook, that the 1969 White Paper of the government of Canada proposed getting rid of the Indian Act and Indian Status. This proposal continues to be resisted by Indigenous people in Canada. In the words of Harold Cardinal,

“We do not want the Indian Act retained because it is a good piece of legislation. It isn’t. It is discriminatory form start to finish. But it is a lever in our hands and an embarrassment to the government, as it should be. No just society and no society with even pretensions to being just can long tolerate such a piece of legislation, but we would rather continue to live in bondage under the inequitable Indian Act than surrender our sacred rights. Any time the government wants to honour its obligations to us we are more than ready to help devise new Indian legislation.”[2].

In 2023 there were more than forty-four Indigenous communities who were free of the Indian Act and operating under a self-government agreement. More than five hundred and fifty communities were still under the Indian Act; however, dozens of these had adopted some kind of legislation to bypass parts of the Indian Act, legislation such as the federal First Nations Land Management Act, or Ontario’s Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement.[3].

Residential Schools:

Residential schools were introduced in the early 1880s. These were to be places run by churches that would teach the English language, the Christian religion, western manners and customs, and trades. As we just learned, the Indian Act gave the federal government permission to compel attendance. Though most First Nations youth did not go to residential schools, of those that did (more than 30% of school aged children in 1944-5)[4], many were whisked away from unwilling parents, usually moving far from home. Students did not know when they would return home, and some never got to visit their families during the summer or at Christmas. In her book, “My Heart Shook like a Drum: What I learned at the Indian Mission Schools, Northwest Territories”, Alice Blondin-Perrin writes of spending six continuous years at residential school, 1952-1959, without ever being able to visit home.

As if this separation from family and culture were not enough, residential schools became known for unsafe construction, inadequate heating, crowding, inadequate food, high mortality rates from illness, zero tolerance by staff of First Nations language and customs, separation of siblings, corporal punishment, and sexual abuse. Justice Murray Sinclair has estimated that as many as 6,000 children may have died at school. About ten years after the last school closed its doors (1997), Canada commissioned a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, led by Justice Sinclair, to fully expose and address this history. Its 2015 report shocked Canadians with accounts of the maltreatment of First Nations children (some Métis and Inuit children included), and of how devastated the children and their communities were when they returned from residential schools emotionally wounded, unable to speak their own language, conditioned to western norms, and having very little experience of good parenting.

Reserves closer to cities often had church-run day schools, not residential schools. Many of these also disregarded Indigenous culture and student welfare.

![Group of female students [7th from left Josephine Gillis (nee Hamilton), 8th from left Eleanor Halcrow (nee Ross)] and a nun (Sister Antoine) in a classroom at Cross Lake Indian Residential School, Cross Lake, Manitoba, February 1940. Credits to: Canada Dept. Indian and Northern Affairs/ Reuters / Library and Archives Canada](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/03/10-1.jpg)

To help understand how this could have happened, we must recall that for centuries, the wealthiest people in Britain and later, in Canada, sent their children to residential schools. It was not considered unkind. It was also not generally known that collections of parentless children are magnets for sadists and child molesters. And schools in remote and isolated areas attract troubled people who cannot be employed anywhere else. Now that we know, let us never forget this.

Residential schools, orphanages, and monasteries full of children continue to exist around the world.

The tragedy of family separation did not end when residential schools closed. While the schools began closing in the 1960s, more and more Indigenous children were placed for adoption by White families, an event now called “The Sixties Scoop”.

There may be some cases when fostering or adoption outside the Indigenous community is the only way to help a neglected or abused Indigenous child. But every time an agency would rather pay non-Indigenous caregivers than assist struggling Indigenous families, we have a continuation of the residential school legacy.

In 2017 there were three hundred per cent more Indigenous children in foster care than there had been in residential school at any one time.[5]. In Alberta, between 1999 and mid-2013, 59% of all children in care were Indigenous, and 78% of children who died in care were Indigenous.[6] According to the 2021 Census, 54% of kids in care in Canada at that time were Indigenous.

Things have been changing for the better. Since 1990, each First Nation has managed its own branch of First Nation Child and Family Services, with funding from government. It was hoped that care would be more culturally sensitive. But hampered by lack of funds, FNCFS branches have not been able to keep all children in the home community. Finally, in February 2018, Indigenous Services Minister Dr. Jane Philpott authorized FNCFS Agencies to spend whatever is necessary to keep children safe in their own communities.

Such a decision answers the first Call to Action in the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. The last call to action is the 94th:

We call upon the Government of Canada to replace the Oath of Citizenship with the following: “I swear (or affirm) that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors, and that I will faithfully observe the laws of Canada including Treaties with Indigenous Peoples, and fulfill my duties as a Canadian citizen.”

- Wilson-Raybould (2022) ↵

- Cardinal (1969) p. 140 ↵

- In Canada, provinces are in charge of Education. ↵

- Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1: Summary, page 62 ↵

- C. Blackstock (2017) ↵

- Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1: Summary, page 141. ↵