Introduction

Origins & Identities:

Before there was Canada, there was Turtle Island – home to the first peoples of North America. Algonquin (al-gon-kwin) and Iroquoian (eer-ah-koy-an) peoples tell the story of a Sky woman falling toward the sea but finding refuge on Turtle, and of a humble creature like Muskrat diving to the bottom of the sea to find the soil needed to build her a home on Turtle’s back.

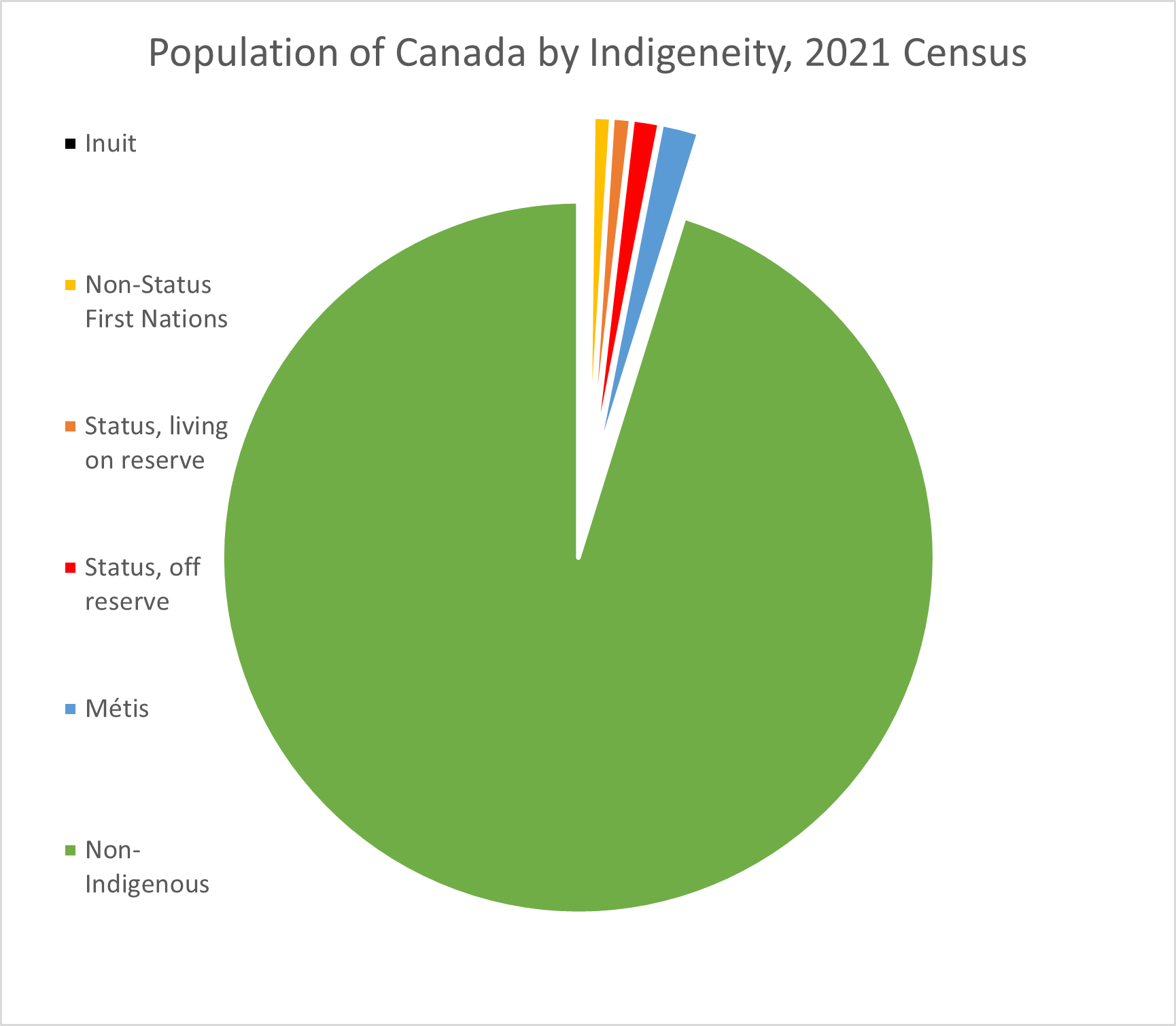

Today we recognize three groups indigenous (in-dih-jen-us) to Canada, descended from the first peoples of Turtle Island: they are the Inuit, the First Nations, and the Métis (May-tee). In 2021 they numbered approximately 1.8 million people, making up 4.9 per cent of the Canadian population.

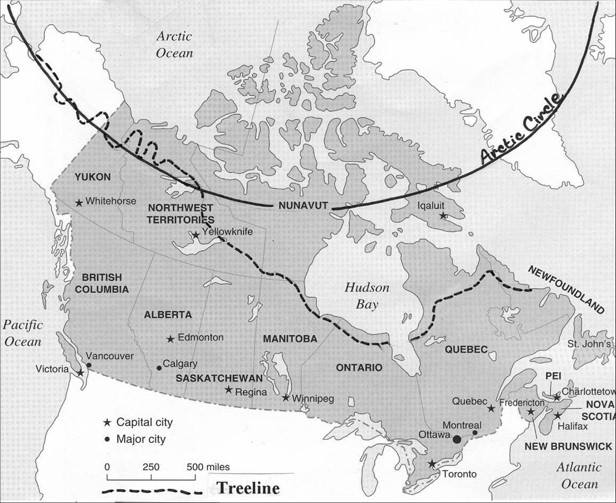

The Inuit are descended from people living north of the tree-line, in the Arctic areas of present-day Canada, prior to European contact. The First Nations are descendants of people living south of the tree-line. The Métis are descendants of multi-generational, intermarrying communities of mixed-race individuals, with Algonquin and French heritages the most pronounced. The dotted line in the Figure below shows the tree-line, above which tree species can only attain the size of shrubs.

Inuit:

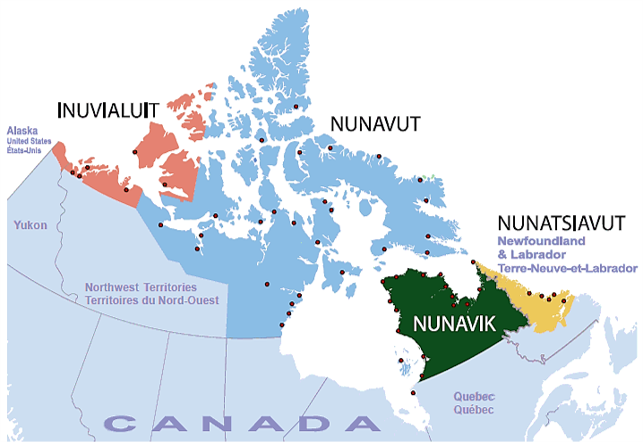

Inuit (in-you-it) Territory or Inuit Nunangat (noo-nan-gat) is divided into four regions: Inuvialuit in the west, Nunavut (noo-na-voot), Nunavik in northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Labrador. Land claim agreements have been signed in all four regions, and Nunavut is politically independent, like other provinces and territories of Canada. In 2021 there were approximately 70,540 Inuit representing 4% of Canada’s Indigenous population. They represent their interests through an organization called Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Although the Inuit had contact with Europeans early on, there was virtually no European settlement on their land, and their lifestyle was not greatly changed by choice or by government until the 1950s. More information on the Inuit and their economies will be presented in Chapters 3, 15, 16, and 29.

First Nations:

The First Nations comprise dozens of cultural groups and 9 language families – from east to west Algonqian, Iroquoian, Siouan (soo-un), Dene (deh-nay), Xaad Kil (Haida), Ktunaxa (Kootenai), Salishan, Tsmishian (shim-shee-un) and Wakashan.

In 2021, people identifying solely as First Nations individuals made up 58% of the self-identifying Indigenous people of Canada. Approximately 72% of them had Registered or Treaty Indian status, meaning that they are officially recognized and recorded as being descended from First Nations people.

While most First Nations people live in cities and towns, there are over 600 recognized Bands – communities of historically-related First Nations families – which have lands allocated them known as “reserves”. It may interest you to know that the amount of land set aside as reserves is only 0.2% of Canada’s land mass [1]. This does not include the larger territories negotiated in modern treaty agreements after 1975. Many First Nations bands do not regard themselves as nations but as part of larger nations sharing a common culture. For example, the six Kanien’kehá:ka (gan-yen-gay-ha-ga) (Mohawk) communities in Ontario and Quebec all consider themselves Kanien’kehá:ka people. The Mohawk nation is itself a member of the Iroquois Confederacy or “Haudenosaunee” (ho-den-oh-show-nee).

Many First Nations bands do not regard themselves as nations but as part of larger nations sharing a common culture. For example, the six Kanien’kehá:ka (gan-yen-gay-ha-ga) (Mohawk) communities in Ontario and Quebec all consider themselves Kanien’kehá:ka people. The Mohawk nation is itself a member of the Iroquois Confederacy or “Haudenosaunee” (ho-den-oh-show-nee).

The composition of communities having First Nations members can vary widely. In large Canadian cities, First Nations individuals are a minority, a minority that may be quite marginalized by the non-Indigenous population. Social segregation is common. In rural and remote areas, community identity may be complicated too.

Consider the case of Moose Factory Island, at the south of James Bay. Moose Factory Island is part of the traditional homeland of the Moose Cree, who gained title to part of the island in Treaty 9. However, the portion of the island where their hospital is located belongs to the federal government of Canada. And another section of the island, which includes the historic Hudson Bay trading post, belongs to the provincial government of Ontario.

The Ililîmowin (Moose Cree) who live at Moose Factory do not all have Registered or Treaty Indian status, a designation of the federal government. It’s possible to lose status, usually after two or three successive generations marrying non-Status partners. We discuss status rights in Chapter 11.

Living alongside the Moose Cree are the MoCreebec. They are Cree who moved to the island from Quebec after Treaty 9 was signed. None of them are covered by Treaty 9. Until the 1990s they were forced to squat on the Ontario portion of the Island in tents and shacks. In 2017 they joined the association of Cree communities on the Quebec side of James Bay, who are covered by the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. This will provide the MoCreebec with administrative support and financial benefits. Also on the Island of Moose Factory are descendants of Moose Cree individuals who intermarried with non-Indigenous, in particular with British Hudson’s Bay Company fur traders. These people were denied status in Treaty 9 because they lived in houses rather than the traditional mikwams (mee-gwams). Meanwhile, across the river from Moose Cree First Nation is the Ontario town called Moosonee. Its population also is mostly Indigenous. In fact, two-thirds of Moosonee residents are Status persons. So what does a First Nations community look like? It’s impossible to generalize!

The Assembly of First Nations represents the interests of Status persons and their Bands to the broader Canadian public. The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples represents Non-Status people of First Nations ancestry, and Métis. In the recent past, the federal government did not recognize any obligation to the Non-Status Indians and Métis; however, the Supreme Court’s Daniels v. Canada decision in 2016 instructed the federal government that these two groups are also “Indians” in the sense of the Canadian Constitution.

Métis:

The Métis represented 35% of Canada’s self-identifying Indigenous people in 2021. Years ago, Métis was the name for children of French fathers and Indigenous mothers. “Country born” was the English expression for children of English fathers and Indigenous mothers. Nowadays, the word Métis has a more precise legal meaning. To be recognized by the government as Métis, you must:

- self-identify as a Métis (of course)

- have an ancestral connection to an historic Métis community

- be recognized as Métis by an established Métis community

Fewer than one-third of people self-identifying as Métis in 2021 would have been able be able to meet those legal criteria, since about thirty-six percent were members of a Métis community or organization, but not all Métis organizations would be recognized in law.

The Métis near present-day Winnipeg were promised land when Manitoba was created in the wake of the Red River Resistance, but the parceling out of land to individuals, often land far from home, served to fragment the community. Only in 1938, and only in Alberta, was land given to Métis communities, many of whom by that time had been reduced to living on the margins of roads and railways. The total amount of land currently assigned to the Métis is comparable to the land mass of Prince Edward Island.

The Métis are represented by the Métis National Council. More on Métis history and culture is presented in Chapters 8 and 9. Besides the Métis National Council, the Assembly of First Nations, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, another important national Indigenous political organization is the Native Women’s Association of Canada, representing Indigenous women.

The pie chart above shows us the distribution of the Canadian population with respect to self-identified Indigeneity, Status, and residence on a reserve. The Inuit are few in number and cannot be visualized on this chart.

624,2200 Canadians identified as Métis in 2021. This includes many individuals who would not be considered Métis according to the current legal definition; however, it likely falls far short of the number of Canadians who have some degree of Indigenous ancestry.

We see that most First Nations, even First Nations with status, do not live on a reserve. In fact, only 41% of First Nations lived on a reserve in 2021, and only 4,238 Métis lived in a Métis settlement.

In a timeless 2013 TED Talk, Gabrielle Scrimshaw has spoken movingly about growing up as a Dene person, and about the untapped potential of Canada’s First Nation youth. In our next chapter we will discuss Indigenous demographics and well-being.

- National summary of the Mineral Resource Potential of Indian Reserve Lands report, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (1991) ↵

A name for North America used by many Indigenous people in Canada and the United States.

Iroquois is a language and cultural group whose members include the Petun, the Neutral, the Wendat (Huron), and the member nations of the Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. The Iroquois practiced agriculture.

Something is indigenous to a place if it has always been there. The Indigenous peoples of Canada lived on Turtle Island before Europeans arrived.

Inuit, meaning "the people" in Inuktitut, the language of the Inuit, lived in the Arctic region of Turtle Island prior to European contact.

Métis are people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry. The legal definition of Métis is more precise, as outlined in Chapter 1.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami is an advocacy organization representing the Inuit of Canada. Its leaders are elected by regional delegates.

A legal status identifying someone as being descended from First Nations who made a treaty or some other agreement with the government of Canada.

A reserve is the land designated for the exclusive use of a First Nation. The community occupying and managing one or more reserves is known as a Band and is made up largely of people sharing common ancestry and having legal Indian Status.

The Mohawk or Kanien’kehá:ka (People of the Flint) are a member nation of the Haudenosaunee. Before 1600 they lived in what is now the United States.

The word federal refers to the government of the nation of Canada.

The Assembly of First Nations is an advocacy organization representing First Nations. Its leaders are elected by First Nations Chiefs.

The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples represents Métis and First Nations people without Registered or Treaty Indian Status. Regional leaders form its Board of Directors while regional delegates vote on who will take on Executive roles.

The founding document of Canada. The first edition, dated 1867, was revised in 1982.

Formerly known as the Red River Rebellion, this event took place in 1870 in present-day Manitoba. It is described in Chapter 9.

The Métis National Council is the advocacy organization for Métis peoples in Canada. The Council is elected by heads of the Métis provincial organizations.