Story Circles

“It brings a sense of community. Because you are in a circle. There’s nobody above or below. We are one. And I think that kind of sets up this catalyst of actions. All the women, ten of us, we were open and a lot of stuff came out when we were doing this. And that evolved into something else.”

— performer-advocate, We Need to Talk!

At its most basic, a story circle is a group of people sitting in a circle sharing stories. Story circles can range from informal gatherings around kitchen tables, living rooms, or campfires, to more formalized and structured events organized with a particular focus in mind. Since most of us have some experience of taking part in either an informal or formal storytelling activity, story circles offer a familiar and convivial entry point into the performance creation workshops.

One common element of formal story circles is that there is no crosstalk. When the storyteller is speaking, everyone else listens. This is often facilitated through the use of an object that the storyteller holds until they are finished with their story. Once they have completed, the teller either passes the object along or sets it down.

TSDC performance creation workshop series usually begin with a story circle. While the facilitator and community worker do not participate in all workshop exercises, as with most Gathering, Checking-in, & Wrapping-up activities, it’s important they always take part fully in the story circles!

Each story circle involves:

- A prompt: a few sentences that invite a specific kind of story that is sent to participants prior to the workshop.

- Objects: we invite participants to bring an object to focus their stories.

- A welcoming space: a low table with a cloth covering and a few chairs allows people to sit on the floor or in a chair, as they wish.

The story circle itself has these key components:

- Each person has a chance to tell their story.

- A response round, where each person has a chance to respond to each other person’s story.

- A collective reflection discussion wraps up the story circle.

A TSDC story circle prompt

The story circle begins prior to the first workshop when participants are sent a prompt. Here’s one that was created for participants who were recruited because of their knowledge of the difficulties of holding on to decent rental accommodations in a rapidly changing Hamilton:

Imagine what Hamilton might be like ten years from now if it were to become a much better City.

What do you imagine life would be like in that much better Hamilton for people with experiences like yours?

Please bring an object that will help you tell a 1 to 3 minute story about something a person with experiences like yours might do in a much better Hamilton 10 years from now. How would life be different for them?

At times, lived experience can be a very individualizing and isolating thing. By inviting participants to consider their personal experience in a collective context (people with experiences like you) the prompt honours participants’ experience while acknowledging them as observers and analysts of the social world. It also recognizes them as being involved in networks of mutual care and support from which they draw knowledge.

![]() The future-oriented aspect of the prompt invites participants to shift their focus from what has or is happening to the kind of world they envision for people with experiences similar to theirs. The prompt’s emphasis on a future vision lets participants know that we are not asking them to report their experience of a particular situation, or their proposed solutions to a particular problem. We are asking about their desires and the kind of world they imagine creating together.

The future-oriented aspect of the prompt invites participants to shift their focus from what has or is happening to the kind of world they envision for people with experiences similar to theirs. The prompt’s emphasis on a future vision lets participants know that we are not asking them to report their experience of a particular situation, or their proposed solutions to a particular problem. We are asking about their desires and the kind of world they imagine creating together.

The story circle provides participants with a performative experience of TSDC’s creative approach and gives them a glimpse into the kind of collective story the process will enable them to co-create and present to a public audience.

The story circle

“It was an amazing feeling to come together around what we dream, and not just around the problems we need to solve. Some people remarked that sharing stories in this way was a deeper emotional process than they had expected. Others felt that the fact of actually handling each other’s objects created a special kind of attention.”

— J. Adam Perry, TSDC research and workshop team member, School of the Arts.

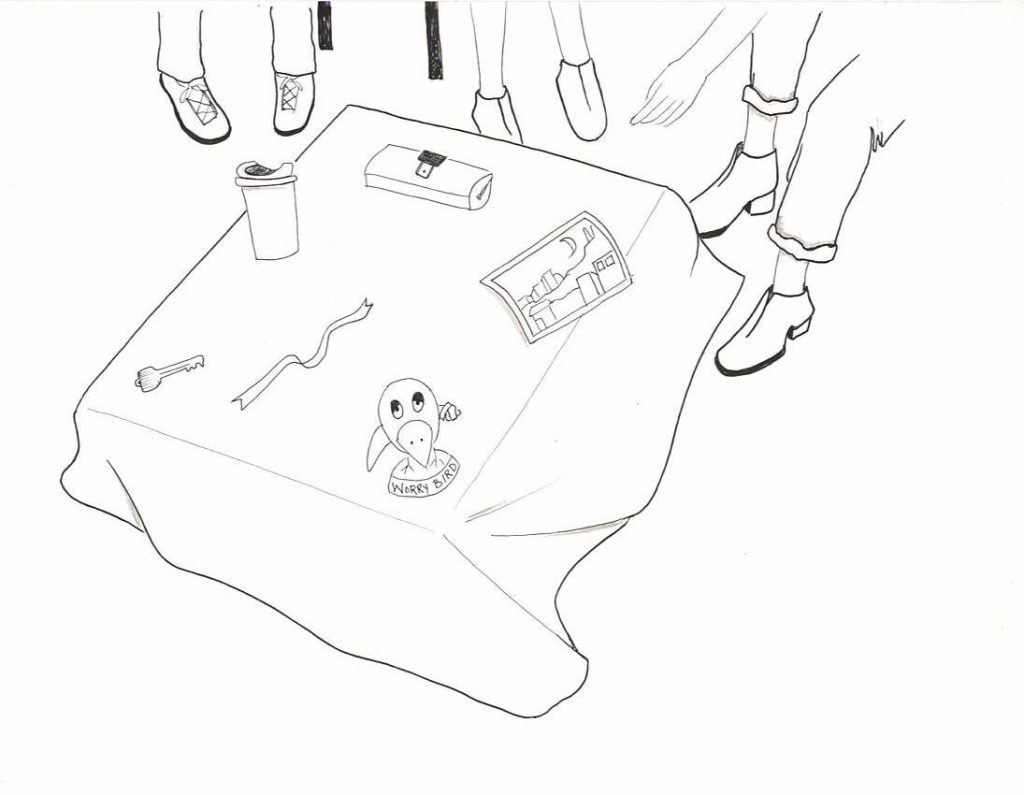

After checking-in and sharing food (something we do at all TSDC workshops), the group sits in a circle. At the centre is a small cloth-covered table for everyone to place their object on. The table acts as an altar, a special place for the story circle objects. A place that says, “These things are important.” “These things, and the stories we tell deserve attention.”

To say that the objects are important doesn’t mean they’re lofty items. They can be anything — a coffee mug, a postcard or photo, a key, a stone, a bus pass. The objects ground us in our material worlds. They communicate that there are things in all of our lives, our worlds, in the stories we tell, that could be the material for building this new world, for building this new vision.

The facilitator briefly explains the storytelling process and then models it by picking up their object and telling a story based on the prompt. Throughout the story circle, only the person holding the object speaks. Everyone else is asked to listen but are also told that they will have an opportunity to respond after the speaker has finished with their story.

The response round

“The very first time we get together in the story circle, everybody gets heard, and everybody gets told that what they said was meaningful, and yet, there is no authoritative meaning imposed. There is no moment of discussion about whether you got it or not, whatever you got is what needs to be gotten from your point of view. It’s one of the things I love about the idea of the circle, we’re all exactly where we should be, seeing exactly what we should see from that position.”

— Catherine Graham, TSDC research team lead and artistic director, School of the Arts.

After each story, the storyteller’s object is passed around the circle until everyone, including the storyteller, who goes last, has a chance to respond to the following questions.

What colour is this story?

What emotion do you associate with this story?

Complete the sentence: “This is the story of a person who…”

These ritualized responses to each story by every listener help shift attention, and thus potential judgment, away from the person telling the story and towards the story itself, along with the social and cultural values it affirms.

We start with the colour question because it makes it clear that there is no ‘correct’ response. Nobody thinks their favorite colour should be everybody’s favorite colour. The neutrality of the colour question lays a foundation for the following question about what emotion the responder associates with the story. Without interrupting the creative flow of the story circle with a lecture about there being no right or wrong answers, the questions are a way to performatively demonstrate that it’s possible to respond to something out of your own feeling about it, and to own, ‘this is my feeling about it.’

It’s not just the content of the stories that are important. It’s the practice of being together, of paying attention, of valuing everyone’s story, and trying to honestly respond. Through the story circle the group enters the collective practice of creating a complex story, or a story with layers of meaning. For example, one person might say, ‘This is the story of a person who is really suffering.’ Someone else might say, ‘This is a person who is really courageous.’ Both things can be true. As we go around the circle, we get a fuller picture of what this story might mean. Other times, as we go around the circle something is re-enforced. If everyone says ‘This is a story of someone who is really courageous,’ we start to understand the story of a single mother who is struggling to raise kids on social assistance as a story of courage, not as the story of failure that it is often portrayed as in the wider world.

Group reflection

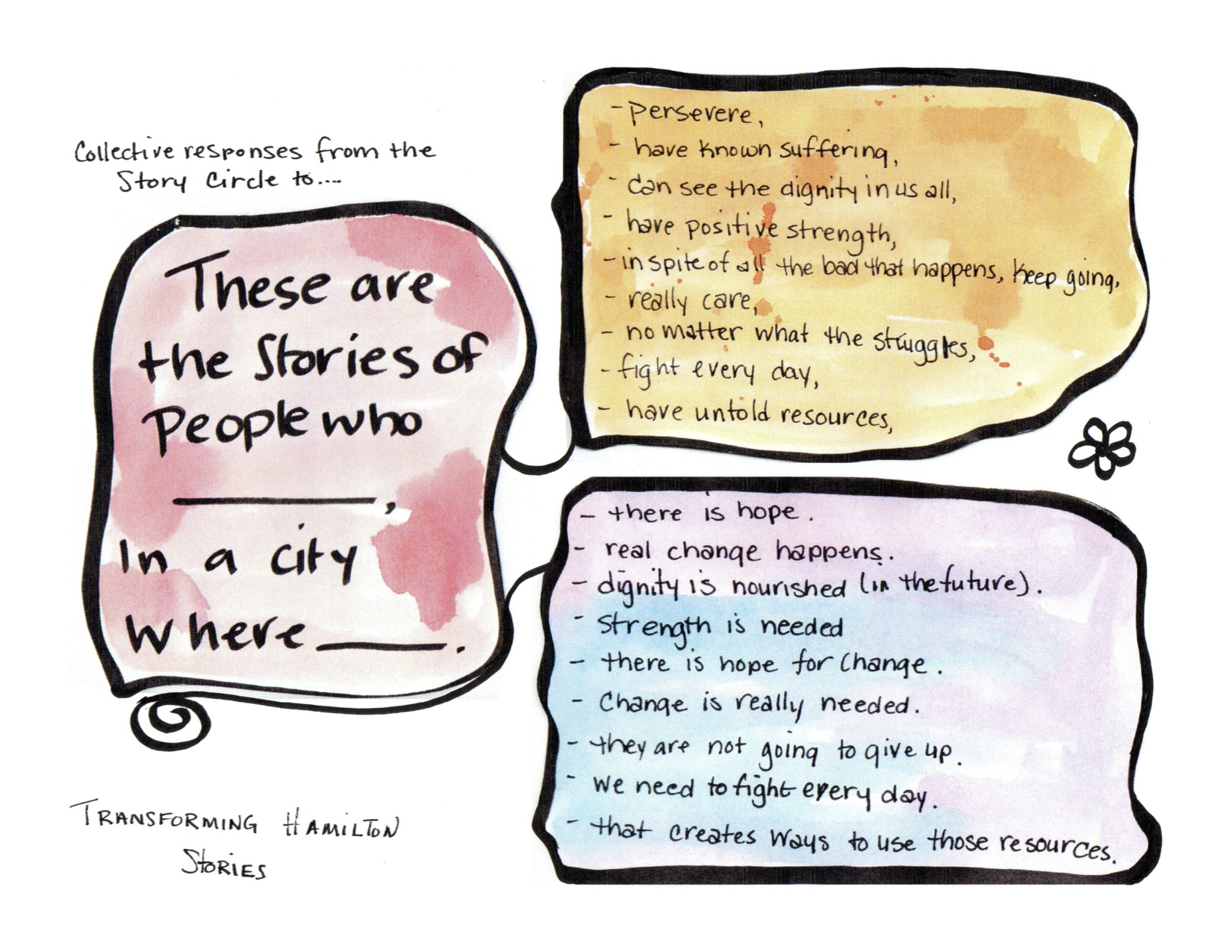

Once each person’s story has been shared and responded to, the group brainstorms responses to the fill-in-the-blank sentence:

These are stories of people who …

in a City where …

The sentence and responses are written on a whiteboard or a large sheet of paper and become the foundation for a post-story circle meaning making discussion exploring the questions: “What do these statements tell us about the kinds of stories we want to tell and the kind of City we want to live in?”

Things to keep in mind:

- Keep the story circles small (usually no more than 6-8 people) to ensure that people don’t feel rushed or overwhelmed. This might mean dividing the group in half with the workshop facilitator and the community worker each facilitating a circle.

- The story circle facilitator introduces the exercise by modeling the different stages of the process.

- Remind participants that only the person holding the object speaks, but that later they will have a chance to respond.

- Be sure to document both the stories and responses as these become sources for identifying themes that emerge.