Choosing a space of public encounter

“All struggles against oppression in the modern world begin by redefining what had previously been considered ‘private,’ non-public and non-political issues as matters of public concern, as issues of justice, as sites of power which need discursive legitimation.”

— Seyla Benhabib. Situating the Self.

Because we work in theatre, after getting a sense of the broader cultural stories that the script will engage, our next step is to choose a physical setting that the story will unfold in. We never set plays in intimate spaces that reflect the characters’ private lives. This is because we don’t want audiences to focus on how individuals might change. Rather, we’re interested in drawing audience attention to how relative strangers are invited (or not invited) to take part in the collective environment of the City. So, we ask ourselves, ‘what kind of public space might the characters that are emerging in the workshop exercises encounter each other in?’

The choice of setting always influences the kinds of interactions that are possible in a performance. Over time, we’ve come to discover that this, in itself, is an important part of the story of how public life is organized. In When My Home is Your Business, for example, it quickly became clear that tenants only really have a right to use the space of their own apartment. Participants told us that landlords often discourage tenants from gathering in shared spaces out of fear of tenant organizing. So, areas that at first glance appear to be shared spaces — lobbies, the mailroom, the area outside the elevators — are, in reality, not intended to be ‘shared.’ They’re designed as temporary spaces for tenants to move through. Through conversations with participants, we saw that the design of the apartment block meant that residents were supposed to remain isolated individuals and were not supported to become neighbours in any real sense. As a result, when characters paused in these spaces to talk, the conversation itself became a kind of challenge to the story the apartment building was designed to tell.

A similar thing happened in the social services offices portrayed in We Need to Talk! The performance space was arranged so that the audience could see multiple characters sitting in an area marked ‘Waiting Room.’ Only one client/character at a time was able to leave the waiting area to approach a case worker. The pattern of movement forced by this spatial arrangement emphasized the limited range of motion available to clients in the face of established bureaucracies.

At the end of the play, the characters moved the chairs so they could sit close together and face the audience. This simple rearrangement of the performance space called attention to how the bureaucratic arrangement of everyday spaces limit possibilities and potential alliances.

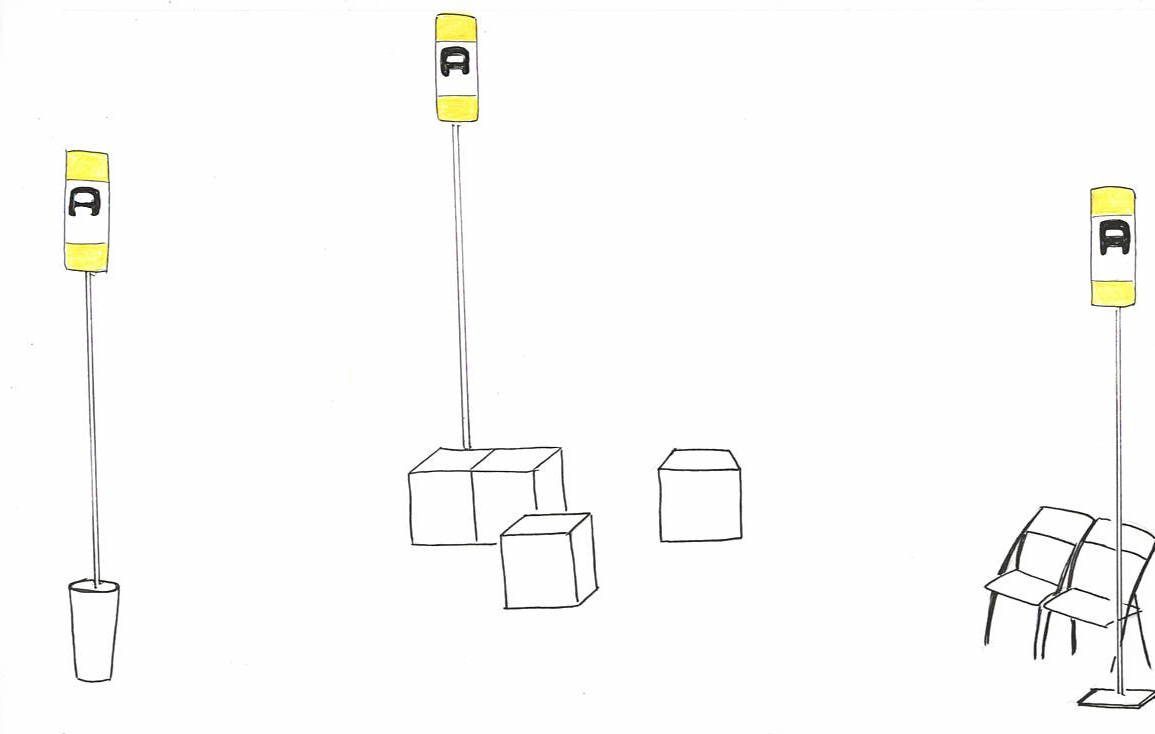

For Choose Your Destination, the performance space was organized around several large wooden boxes that were used to represent seats on a City bus. Three bus stop signs were also placed in different areas of the space. During the workshops, the youth had created scenes that took place in multiple different locations.

The choice of a City bus as a focal point where they might meet helped us address two of the play’s practical storytelling problems:

- The bus provided us with a space where characters who didn’t start off knowing one another could meet and develop relationships.

- The bus stops allowed us to stage action in multiple locations around the City without having to create a set for each location.

The bus also contributed in significant ways to the play’s narrative and meaning. On a tangible level, the bus reflected a reality of everyday life in Cities. Public transit is one place people encounter each other. When people travel the same routes regularly strangers may come to know each other a bit even though they lead very different lives. But importantly, the bus also gave us a way to metaphorically point to the core repeating narrative of the play: the youth were constantly trying to take care of themselves after being let down by adults in their lives. Despite being let down, time after time, they ‘got back on the bus,’ tried again, and helped one another while they continued on their journeys.