Collectively imagining a better future through performance

“I’ve long struggled as a social service provider who has some responsibility around fundraising, with how the voices and stories of the folks we serve are used in very particular ways. I love the idea of groups of folks coming together and sharing their stories and creating something really meaningful, educational, and invigorating without having to personally reveal the most painful pieces of their past.”

— Katherine Kalinowski, Chief Operating Officer, Good Shepherd Centres, Hamilton.

There are many ways of telling stories, many tellers, and many reasons for telling. Stories can build group cohesion. Stories can serve as resources for individual and collective healing. They can educate and advocate. They can be vehicles of personal, cultural, or political testimony. They can generate empathy. They can also expose individuals and groups to harm in the form of negative public scrutiny. They can include. They can exclude. Stories can help us remember. They can bring attention to the conditions of our present. And they can be a way to collectively imagine better futures.

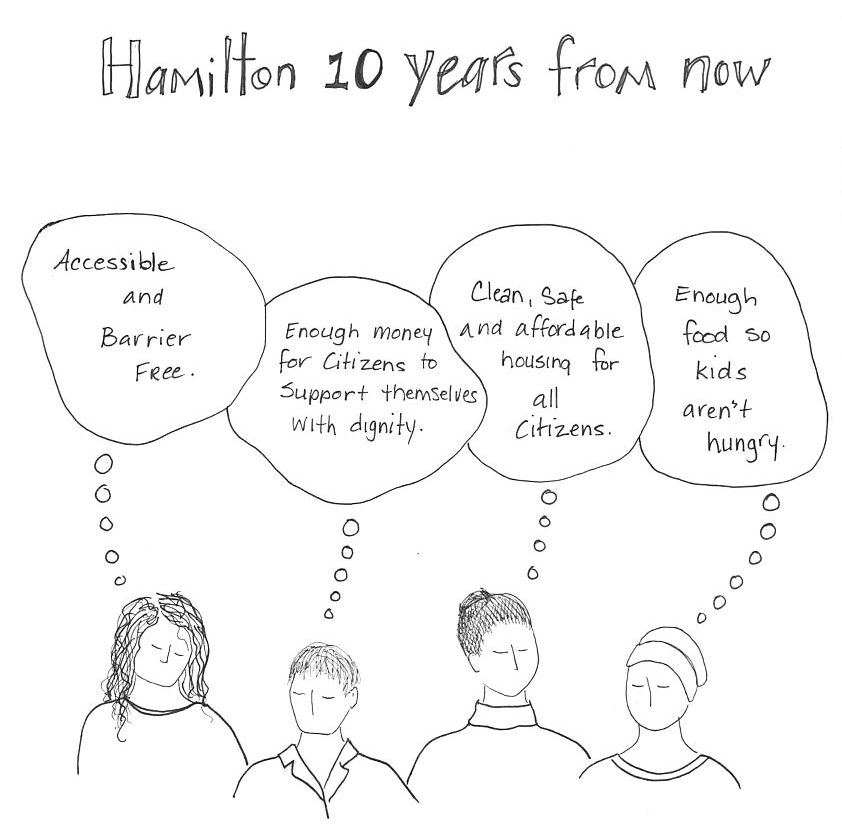

TSDC stories take the form of short plays designed to bring voices that are not currently being heard into public discussions about our collective future. When we began TSDC as a pilot research project in 2014, we wanted to see what would happen if we invited community groups advocating for change to use performance-based storytelling activities to communicate their hopes and priorities for Hamilton, this City we shared. In fact, these questions became the basis of a story prompt that animates our workshops and public events: “Imagine what Hamilton might be like ten years from now if it were to become a much better City. What do you imagine life would be like in that much better Hamilton for people with experiences like yours?” (More on prompts in a bit!)

In the years since that first pilot project, TSDC productions have included performances about living in inhospitable and precarious housing (When My Home is Your Business), dealing with the narrow mandates and inflexibility of social services (All Of Us Together & We Need to Talk!), and working to overcome barriers and negative perceptions as homeless or street involved young people living in Hamilton (Choose Your Destination).

We know that many people have been excluded from conversations about the future of Hamilton. We also know it’s not because they have nothing to say. Rather, we believe it’s because only certain speakers are recognized as legitimate and only certain ways of speaking are heard or recognized as worthy contributions to the conversation. This problem of exclusion isn’t unique to Hamilton. As political theorist Nancy Fraser argues, communication norms produce a kind of “misrecognition”[1] wherein speakers from marginalized communities can become seen as mere illustrations of social problems, rather than heard and heeded as agents of social change.

This is the impetus behind TSDC: The development of a performance creation approach designed to communicate stories that are grounded in knowledge based on lived experiences to a broader public. By framing stories in a public (social) and collective context, TSDC plays evade some of the limitations and difficulties of autobiographical or individual narratives (see table below). Our intention with this workbook is to share what we’ve learned. We dedicate it to all the performer-advocates whose creative risk-taking has inspired its writing.

Personal Stories:[2] Value of, problems with, and TSDC’s approach

| Value of personal stories | Problems with personal stories | TSDC’s creative approach |

|---|---|---|

|

Personal stories activate empathy by making potentially distant experiences more emotionally and conceptually accessible. |

Public sharing of personal stories places individuals in a position of disclosure and vulnerability to public scrutiny. |

Using a fictional approach provides a way for personal stories to be publicly heard, without exposing details about individual participants lives. |

|

Personal stories bring together communities with shared histories, identities, or life experiences. |

Personal stories can risk individualizing or localizing broader public and social problems. |

Audiences do not know what aspects of a collectively devised story are actually ‘true’ for any individual performer. |

|

Personal stories can help repair or build social relationships between groups and individuals in conflict or crisis. |

In many contexts personal stories are easily dismissed or seen as applying only to the individuals and groups directly involved. |

Focusing on publicness bolsters community and self-advocates entitlement to be heard and chances of being heard. |

|

Personal stories can counter dehumanizing discourses and images. |

Personal stories often orient to immediate daily struggles as individual problems that need to be addressed. |

Focusing on future and desire establishes speakers as contributors to wider longer-term conversation about the kind of City they (alongside other residents) wish it to be. |