Identifying core cultural stories

“The title, Choose Your Destination, had many meanings to all of us involved in the project. But among them was the idea that as people navigate the everyday hustle and bustle of the City, they are employing agency. That agency can be constrained by the City and the barriers that it imposes, but it can also shape the City itself, how it is viewed and how it is experienced. For me, Choose Your Destination has a more literal meaning. It is an invitation to think about the kinds of spaces we create and to think carefully about the impact on the young lives forming here. It is an invitation to build spaces centered around comfort and warmth, learning and growth. It is an invitation to build spaces that can turn into meaningful places for everyone.”

— Sarah Adjekum, TSDC research assistant and member of the Choose Your Destination workshop team.

Stories do not, and cannot, operate outside of the larger shared social contexts we reside in (town, City, nation). In every society there are stories that float to the surface and get taken up for different purposes. These core ‘cultural’ stories shape our perspectives and expectations. They create a sense of what’s important to pay attention to and of how to make meaning of situations. They influence the decisions we make about how we construct our shared social world. Often, they take the form of popularized adages.

Here’s a small sampling of dominant stories that shape our expectations about how people should behave:

- People get what they deserve

- Anyone who tries hard will succeed

- We don’t need others: we can (and should) pull ourselves up by our bootstraps

- Sacrifice now, leads to rewards later

- The cream rises to the top (leaders in our City are the smartest, most capable people in the City)

- Don’t rock the boat

Of course, cultural stories change over time. They are also often contradictory and can mask unspoken social and political biases. So, when creating scripts for TSDC performances one of the first things we look for are the broader cultural stories (or dominant discourses) that are being used to make the events that participants describe meaningful to different audiences. We then create a story framework that re-frames these cultural stories by telling it from the point of view of the play’s performer-advocates. To do this, we look for tensions, contrasts, and contradictions between what participants show and tell us about their lived experiences during workshop improvisations and discussions, and what the dominant cultural stories tell us about their lives, situations, and experiences.

In some cases, this means noticing the contradiction between themes that are emerging in the workshop and a dominant story. For example, as we developed We Need to Talk!, the facilitators were struck early on by the overwhelming amount of work and planning participants are required to do to get the most basic resources, and the apparent lack of motivation of many service providers to help them in meaningful ways. One reason this stood out to us is because of how it conflicted with the stories we often hear in broader public discourse that imply that people who live in poverty do nothing all day, are unmotivated to change their situations, or are just lazy.

Other cases, like in When My Home is Your Business workshops, showed two conflicting stories operating in the same physical environment (an apartment building). Tenants tell stories about trying to be good neighbours in buildings where repairs are never done, and everyone is on edge because they live with the constant threat of eviction. Landlords and superintendents of rental buildings tell a very different story. They speak of being efficient and responsible businesspeople by charging the maximum rent possible while minimizing spending on the building. Or, in times of ‘urban renewal,’ they speak about how the positive impacts of ‘redevelopment’ projects justifies the displacement of tenants.

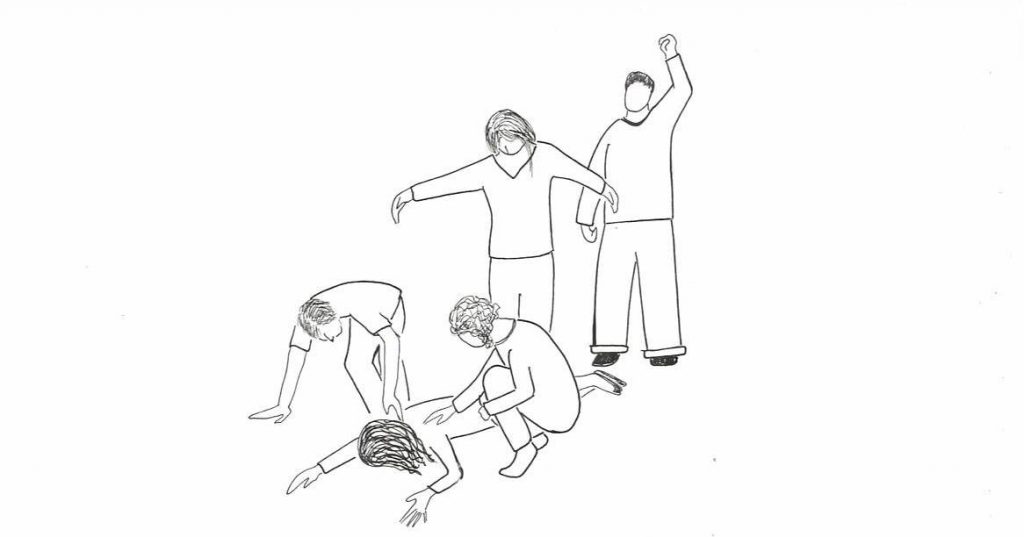

Some conflicting stories or contradictions are immediately visible through the workshop exercises. This was the case in one Image Theatre improvisation we did with participants from All of Us Together. The image began with one workshop participant lying on the floor. As other participants joined the image, they leaned over the person on the ground and gestured as though offering to help. The last workshop participant to join the image stood behind the gathered group and raised her fist in the air.

The collective image poignantly captured the dilemma anti-poverty activists often face: the tension between how much energy we put into helping individuals who are hurting, and how much energy we put into challenging or undoing the system causing hurt. In this case, the tension was less about opposing or contradictory narratives, and more about drawing attention to the different pathways or strategies available to resolve or address social problems.

Keep in mind that, often, neither the facilitators nor the participants are immediately aware of the core and conflicting stories as they emerge in workshop exercises. This is why repetition and documentation are so important! It took us a long time to figure out the core story when we were working with a group of precariously housed youth on the performance, Choose Your Destination. It was only after paying attention through multiple workshops and reviewing the documentation of many Image Theatre improvisations that we began to recognize the core story: the youth who had been let down by the adults in their lives were constantly on guard against threats and disappointments, and yet consistently looked for other solutions and worked to move towards them, often supporting each other.