Infections and Our Bodies

What Is an Infection?

An infection is the successful colonization of a host (individual) by a microorganism. Infections can lead

to disease, which causes signs and symptoms reflective of a deviation from the normal structure or functioning of the susceptible host. Microorganisms that can cause disease are known as pathogens. Multiplication of the pathogen leads to infection.

Depending on the extent of the infection, infections can be described in three ways:

Signs and Symptoms

The signs of infection are objective and measurable, and can be directly observed by a healthcare provider. One sign of infection is vital signs, which are used to measure the body’s basic functions. Changes in vital signs may be indicative of disease. For example, having a fever is a sign of infection because it can be measured.

Other observable conditions that may be considered signs of disease are the presence of antibodies in a client’s serum (the liquid portion of blood that lacks clotting factors), which can be measure through blood tests. However, the presence of antibodies is not always a sign of an active disease. Antibodies can remain in the body long after an infection has been resolved; also, they may develop in response to a pathogen that is in the body but not currently causing disease.

Symptoms of disease are subjective and are felt or experienced by the client. Examples of symptoms include nausea, loss of appetite, and pain. Such symptoms are important to consider when diagnosing disease, but they are subject to memory bias and are difficult to measure precisely.

Healthcare providers must rely on signs and on asking clients about their symptoms, medical history, and recent activities to identify a particular disease and the potential causative agent. Microorganisms can cause similar signs and symptoms in a client. For example, an individual presenting with symptoms of diarrhea may have been infected by one of a wide variety of pathogenic microorganisms. Bacterial pathogens include Clostridium difficile, viral pathogens include norovirus and rotavirus, and parasitic pathogens include Giardia lamblia. All are associated with diarrhea. Likewise, fever is indicative of many types of infection, from the common cold to the deadly Ebola hemorrhagic fever. Looking for other signs like abdominal distension and bloating, and symptoms like flatulence, cramping, and discomfort, can help you make the connection to common traits associated with pathogens.

Some diseases may be asymptomatic, meaning they do not present any noticeable signs or symptoms. For example, most individuals infected with herpes simplex virus remain asymptomatic and are initially unaware that they have been infected until it manifests as a lesion.

Classifications of Diseases

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is used in clinical fields to classify diseases and monitor morbidity (the number of cases of a disease) and mortality (the number of deaths due to a disease).

Acute, Chronic, and Latent Diseases

The duration of the period of illness can vary greatly, depending on the pathogen, effectiveness of the immune response in the host, and any medical treatment received. In an acute disease, the pathologic changes occur over a relatively short time (e.g., hours, days, or a few weeks) and involve a rapid onset of disease conditions. For example, the influenza incubation period is approximately 1–2 days. Infected individuals can spread influenza to others for approximately 5 days after becoming ill. After approximately 1 week, individuals enter the period of decline.

A chronic disease occurs over longer time spans (e.g., months, years, or a lifetime). Hepatitis B virus can cause a chronic infection in some clients who do not eliminate the virus after the acute illness. Chronic hepatitis B virus continues production of the infectious virus for 6 months or longer after the acute infection.

In latent diseases, the causal pathogen goes dormant for extended periods of time with no active replication. Examples include herpes, chickenpox, and mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus). These diseases evade the host immune system by residing in a latent form within cells of the nervous system for long periods of time, and can reactivate to become active infections during times of stress and immunosuppression.

Both latent and chronic diseases can have acute flare-ups that require prompt intervention.

Pathogenicity and Virulence

The ability of a microbial agent to cause disease is called pathogenicity, and the degree to which an organism is pathogenic is called virulence. Virulence is a continuum. On one end of the spectrum are organisms that are avirulent (not harmful) and on the other end are organisms that are highly virulent.

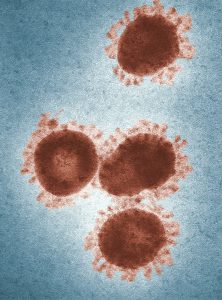

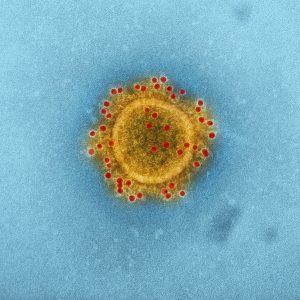

Highly virulent pathogens will almost always lead to a disease state when introduced to the body, and some may even cause multi-organ and body system failure in healthy individuals. For example, COVID-19 is a virulent virus that affects multiple systems (e.g., lungs, heart, kidneys).

Highly virulent pathogens will almost always lead to a disease state when introduced to the body, and some may even cause multi-organ and body system failure in healthy individuals. For example, COVID-19 is a virulent virus that affects multiple systems (e.g., lungs, heart, kidneys).

Less virulent pathogens may cause an initial infection, but may not always cause severe illness. Pathogens with low virulence would more likely result in mild signs and symptoms of disease, such as low-grade fever, headache, or muscle aches. Some individuals might even be asymptomatic. For example, some strains of hand-foot-and-mouth disease can be mild or even asymptomatic.

Body Defence Mechanisms

Despite relatively constant exposure to pathogenic microbes in the environment, humans do not generally suffer from constant infection or disease. Under most circumstances, the body is able to defend itself from the threat of infection thanks to a complex immune system designed to repel, kill, and expel disease-causing invaders.

Physical Defences.

Physical defences provide the body’s most basic form of nonspecific defence. Physical barriers play an important role in preventing microbes from reaching tissues that are susceptible to infection. One of the body’s most important physical barriers is the skin. The mucous membranes lining the nose, mouth, lungs, and urinary and digestive tracts provide another nonspecific barrier against potential pathogens. The epithelial cells lining the urogenital tract, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and certain other tissues is another physical barrier.

Mechanical Defences

Mechanical defences physically remove pathogens from the body, preventing them from taking up residence. Examples include the shedding of skin cells, the expulsion of mucus, the excretion of feces through intestinal peristalsis, and the flushing action of urine and tears. Chemical mediators include sebaceous glands, saliva, mucus, urine, lactate, and tears.

Cellular Defences

Cellular defences are located in the blood, which includes red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells.

Inflammation results from the collective response of chemical mediators and cellular defences to an injury or infection. Acute inflammation is short-lived and localized to the site of injury or infection. Chronic inflammation occurs when the inflammatory response is unsuccessful, and may result in the formation of granulomas (e.g., with tuberculosis) and scarring (e.g., with hepatitis C viral infections).

The five cardinal signs of inflammation are:

- Erythema

- Edema

- Heat

- Pain

- Altered function

These largely result from innate responses that draw increased blood flow to the injured or infected tissue (the body’s natural response and attempt to flush out the pathogen). Fever is a system-wide sign of inflammation that raises the body temperature and stimulates the immune response (in an attempt to kill the pathogen). Both inflammation and fever can be harmful if the inflammatory response is too severe.

Test your Knowledge

Attribution

This page was remixed with our own original content and adapted from:

Microbiology by Nina Parker, Mark Schneegurt, Anh-Hue Thi Tu, Philip Lister, Brian M. Forster is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 Licence.