9 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Introduction

The seven sacred teachings form a framework for this discussion on the Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada (TRC). It takes courage to tell the truth and allow it to be heard and witnessed. Thus, this section on the TRC is called “Courage.”

Defining “Reconciliation”

The Oxford Dictionary defines reconciliation as “the restoration of friendly relations” (“Reconciliation,” n.d.).

Many would argue that a state of “friendly relations” between non-Indigenous people and Indigenous Peoples in Canada has never existed in a meaningful way. Thus, returning to such a state is impossible (TRC, 2015a, p. 3). However, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada adopted a broader perspective:

To the Commission, “reconciliation” is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. For that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.

The TRC sees reconciliation as “coming to terms with events of the past in a manner that overcomes conflict and establishes a respectful and healthy relationship among people going forward.” (TRC, 2015a, p. 3)

The TRC

In June 2009 the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair was appointed chairperson of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Marie Wilson and Chief Wilton Littlechild were appointed as commissioners. These three individuals formed the TRC.

Beginning in 2009, the TRC was charged with a five-year mission: to inform Canadians about what happened in Indian Residential Schools (IRS). “The Commission documented the truth of survivors, families, communities, and anyone personally affected by the IRS experience” (TRC, 2009).

The TRC collected more than 6750 statements from residential school survivors and others impacted by the IRS experience. Most statements were recorded digitally (audio or video), creating a total of 1355 hours of recordings. The majority of statements were gathered at seven national events and numerous regional events and community hearings (TRC, n.d.-d; Schwartz, 2015).

To collect these statements, the TRC travelled across Canada to meet with residential school survivors. As part of the TRC’s official mandate, each event had to be organized and held in a culturally appropriate way that provided a “safe, supportive and sensitive environment for individual statement taking/truth sharing” (TRC, n.d.-d).

A critical element for survivors was the presence of honorary witnesses to hear, validate, and remember the truths they had the courage to share.

Truth: Honorary Witnesses/Witnessing

Speaking to [the TRC] at the Traditional Knowledge Keepers Forum in June 2014, elder Dave Courchene posed a critical question: “When you talk about truth, whose truth are you talking about?”

The Commission’s answer to Courchene’s question is that by truth we mean not only the truth revealed in government and church residential school documents but also the truth of lived experiences as told to us by survivors and others in their statements to this commission. Together, these public testimonies constitute a new oral history record, one based on Indigenous legal traditions and the practice of witnessing. (TRC, 2015a, p. 7)

The term “witnessing” refers to an important Indigenous principle. Its practice somewhat varies between First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, but the principle is common to all: “Generally speaking, witnesses are called to be the keepers of history when an event of historic significance occurs” (TRC, n.d.-c). This occurs partly because of the oral traditions of Indigenous Peoples, but the act of witnessing also recognizes “the importance of building and maintaining relationships face to face” (TRC, n.d.-c).

Through witnessing, an event is validated and legitimized. “Witnesses are asked to store and care for the history they witness and, most importantly, to share it with their own People when they return home” (TRC, n.d.-c).

As the TRC travelled across Canada, honorary witnesses were present at each event: “Their role was to bear official witness to the testimonies of survivors and their families, former school staff and their descendants, government and church officials, and any others whose lives have been affected by the residential schools” (TRC, 2015a, p. 7).

Movie 2.1 TRC honorary witnesses

Michaëlle Jean Welcomes Honorary Witnesses from TRC – CVR on Vimeo.

Message from the Rt. Hon. Michaëlle Jean to TRC honorary witnesses.

The Results of the TRC’s Work

The TRC’s final report was delivered in a ceremony on December 15, 2015. As a result of this work, we now know the following:

- Over 150,000 children from First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities were placed in residential schools from 1883 to 1996.

- Although the TRC confirmed 3201 deaths within the named and unnamed registers of IRS (TRC, 2015b, p. 92), it is estimated that over 6000 children died in residential schools (Fortune, 2018). These deaths were caused by disease (tuberculosis and influenza in particular), neglect, abuse, lack of food, isolation from family and culture, insufficient housing, exposure to the elements, and fires.

- As of 2015 there remained over 80,000 survivors of residential schools still living.

- There have been 37,965 claims made by survivors for compensation for sexual abuse while in residential schools. This number represents 25 percent of the total number of children who were placed in the care of these institutions (Schwartz, 2015).

Most importantly, the TRC made 94 calls to action.

Interactive 2.1 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Click the above link to open and read all 94 calls to action in PDF format.

Love: Calls to Action

As noted by philosophers and theists alike, love without action or sacrifice is just a word. Thus, the section on calls to action is labelled after the sacred teaching of “Love.”

The 94 calls to action are grouped under two broad categories:

- Legacy: to redress the deep, residual cultural and psychological damage of residential schools; and

- Reconciliation: to advance the process of reconciliation in Canada between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Calls to action 58 through 61 call for the Pope, as the representative of the Catholic Church, and other church parties involved in residential schooling, to both apologize and to educate their congregations on “why apologies to former residential school students, their families, and communities were necessary” (TRC, 2015c, p. 6). To achieve this, governments at all levels, the Catholic Church, and other church parties would need to embrace the sacred teaching of “Humility.”

The calls to action in the TRC’s final report are more than mere recommendations. They underpin the sacrifices and actions that are needed to create a foundation for true reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians.

The calls to action will touch, and possibly deeply reform, the operation and communications of the following organizations. Each effort made by these organizations to incorporate the calls to action into their work represents a step forward towards reconciliation.

Calls to Action: Summary

The 94 calls to action are specific and very clear, and are available in full by clicking on the report below. The following is a summary of some of the areas that are addressed in the calls to action. Remember when reading the calls to action that there are two sections: legacy recommendations (to correct historical wrongs) and reconciliation recommendations (which are about ways to improve on current issues and concerns). Some areas of concern are listed in both sections.

Child Welfare

This area focuses on measures to reduce the number of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children in care, by improving supports and education for social service workers. Related calls to action highlight the importance of implementing equity in health care, and of creating national standards for culturally appropriate care.

Education

This substantive area calls for closing the gaps in both opportunities and outcomes that persist between First Nation, Inuit, and Métis students and their non-Indigenous counterparts. The recommendations cover curriculum, funding gaps, and the delivery of culturally appropriate content across Canada.

Health

The health-focused calls to action demand that health-care professionals be better educated about Indigenous Peoples, and, as with the educational recommendations, an important focus is closing the gaps that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in terms of health and well-being. The recommendations cover both on- and off-reserve populations, and highlight the importance of valuing Indigenous health practices and traditional forms of care.

Justice

The recommendations in this area call for culturally appropriate policing and justice, and address specific issues, such as the treatment of people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Related calls to action also speak to the need for culturally relevant education for lawyers, and for increased and adequate funding for supports and services for Indigenous Peoples involved in the justice system.

Interactive 2.2 Rhiannon Johnson, Indigenous journalist

Rhiannon Johnson discusses her work as a journalist and some of the ways that Indigenous peoples are covered by the media in Canada.

Calls to Action: Newcomers to Canada

The calls to action with respect to newcomers to Canada are not actions that newcomers themselves will take; rather, they involve changes to citizenship education and the citizenship test, as well as to the oath (to the Queen) that all new Canadians take to become citizens. Many newcomers to Canada arrive from parts of the world where colonization has also resulted in violence, systemic oppression, racism, and torture. There is common ground between Indigenous Peoples and these newcomers, but the ability to develop dialogue and connection is not well-established in the current government-led process (TRC, 2015a, p. 214). Without education about and awareness of Indigenous Peoples, newcomers cannot become allies.

Discover Canada, a booklet studied by all immigrants to Canada, explains that “to understand what it means to be Canadian, it is important to know about our three founding peoples—Indigenous, French and British.” In describing Canada’s legal system, Discover Canada states:

Canadian law has several sources, including laws passed by parliament and the provincial legislatures, English common law, the civil code of France and the unwritten constitution that we have inherited from Great Britain. Together, these secure for Canadians an 800-year-old tradition of ordered liberty, which dates back to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215 in England. (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2012, p. 8)

Indigenous Peoples have been a vital source of law for Canada, yet Citizenship and Immigration Canada omits this fact from this important orientation resource, which also states that Canada’s Indigenous Peoples “welcomed the European explorers, helped them survive in this climate, guided them throughout the country, and entered into treaties with them to share their land” (TRC, 2015a, p. 216), without also mentioning the conflicts, injustice, or ongoing land claims that are evidence of a much more fraught history.

Call to action 94 proposes updating the citizenship oath to include a solemn promise to respect Indigenous and treaty rights. The current oath reads as follows:

I swear (or affirm) that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors, and that I will faithfully observe the laws of Canada and fulfill my duties as a Canadian citizen.

The proposed new oath would read as follows:

I swear (or affirm) that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors, and that I will faithfully observe the laws of Canada including Treaties with Indigenous Peoples, and fulfill my duties as a Canadian citizen. (TRC, 2015a, p. 217)

Calls to Action: Missing and Buried Children

As noted earlier, death rates for residential school children were substantially higher than those for the rest of the Canadian population (TRC, 2015b). Many families suffered the indignity of not being able to bury these children:

The general Indian Affairs policy was to hold the schools responsible for burial expenses when a student died at school. The school generally determined the location and nature of that burial. Parental requests to have children’s bodies returned home for burial were generally refused as being too costly. […] As late as 1958, Indian Affairs refused to return the body of a boy who had died at a hospital in Edmonton to his home community in the Yukon. (TRC, 2015b, p. 100)

Redress for the deep lack of respect for the corporeal and spiritual lives of these children, and the grief and spiritual suffering of their families, is sought in calls to action 75 and 76.

Humility: Federal Apologies

By the time residential school survivors won a class action lawsuit against the Government of Canada in 2006, the Presbyterian and United Churches, and the RCMP, had already apologized for their roles in the residential school system. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established nine days before the first federal apology in 2008.

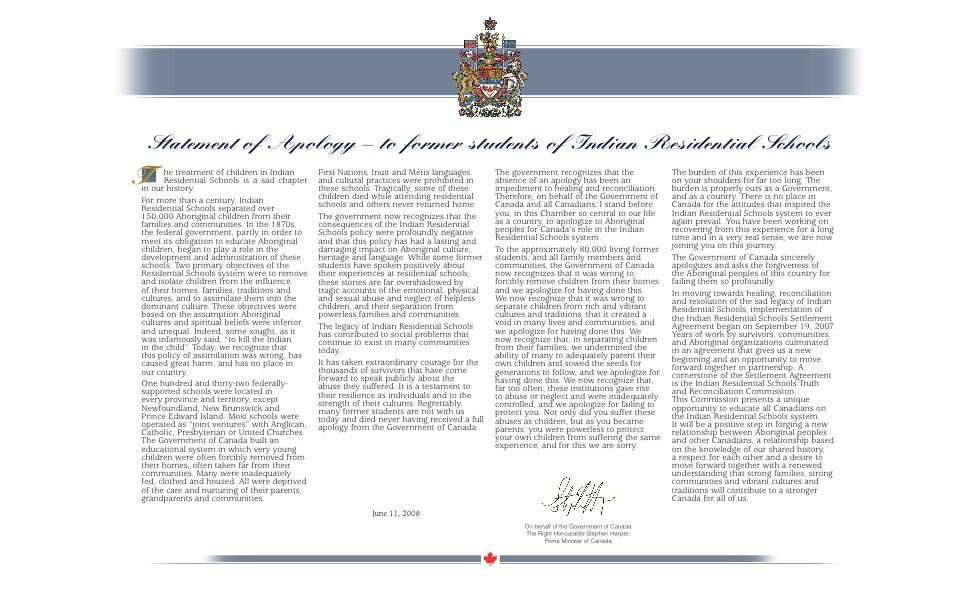

2008 Apology

Prime Minister Stephen Harper read an apology on behalf of the Government of Canada on June 11, 2008. In this apology, the prime minister stated that “the burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. The burden is properly ours as a Government, and as a country. There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential School system to ever prevail again. You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey.”

Prime Minister Stephen Harper read an apology on behalf of the Government of Canada on June 11, 2008. In this apology, the prime minister stated that “the burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. The burden is properly ours as a Government, and as a country. There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential School system to ever prevail again. You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey.”

This apology came with a compensation package for residential school survivors and their descendants; however, this package did not cover survivors of residential schools not overseen by the federal government. The federal government of 2008 argued that it had “no fiduciary obligation to survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador because the province was not part of Canada when the schools began operating” (Brake, 2017).

2017 Apology

Interactive 2.3 2017 apology

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issues an apology to Indigenous Peoples in Newfoundland and Labrador.

In 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau gave an apology to the survivors of several residential schools in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Prior to delivering the apology, a class action lawsuit was settled, awarding previously excluded survivors a $50-million settlement. Residential school survivor Toby Obed, who was one of the main drivers of the class action lawsuit, accepted the prime minister’s apology on behalf of other school survivors: “This apology is an important part of the healing. Today the survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador we can finally feel a part of the community of survivors nation-wide across Canada. We have connected with the rest of Canada – we got our apology” (Canadian Press, 2017).

It is important to note that neither of these apologies addressed the survivors of day schools, who have still not been included in most accounts of residential schools. These survivors are currently pursuing their own class action lawsuit.

Wisdom: The Role of Art in Reconciliation

In its report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission highlighted why the arts are so important to the reconciliation process.

The arts help to restore human dignity and identity in the face of injustice. Properly structured, they can also invite people to explore their own world views, values, beliefs, and attitudes that may be barriers to healing, justice, and reconciliation. (TRC, 2015b, p. 280)

Furthermore cultural and artistic expression is often denied to oppressed peoples to make them lose their identities and be forced to assimilate.

Participation in the arts is a guarantor of other human rights because the first thing that is taken away from vulnerable, unpopular or minority groups is the right to self-expression. (F. H. Paget to Frank Pedley as quoted in TRC, 2015b, p. 280)

Acknowledging its power, the commission sought to incorporate art into its reconciliation work. It held a number of major art exhibits at the same time as its national events. The art exhibited was by both Indigenous artists, some of whom had been in residential schools or were intergenerational survivors, and by non-Indigenous artists. Themes included “denial, complicity, apology, and government policy” (TRC, 2015b, p. 281).

Survivor Statements in Art

Many survivors were able to transcend painful memories and find their voice by creating a poem, a song, a video or audio recording, a photograph, a theatre performance piece, a film, a blanket, a quilt, a carving, or a painting “to depict residential school experiences, to celebrate those who survived them, or to commemorate those who did not” (TRC, 2015b). The role of art in the reconciliation process “rests in its ability to say the unsayable. Art give us a way to access even the most difficult things – those things for which we can’t find the words,” notes Jonathan Dewar, executive director at the First Nations Governance Centre in Ottawa (Dewar as quoted in Sandals, 2013).

TRC-Funded Art Initiatives

The TRC sponsored a number of art initiatives as part of its work. Some of them are described here.

The Living Healing Quilt Project

Gallery 2.1 Quilt series for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The Living Healing Quilt Project was organized by Anishinaabe quilter Alice Williams from Curve Lake First Nation in Ontario. Individual quilt blocks were created by women survivors and intergenerational survivors from across the country. These quilt blocks depicted memories of residential schools and were eventually stitched together into three quilts: Schools of Shame, Child Prisoners, and Crimes Against Humanity (TRC, 2015b).

The Bentwood Box: 7,000 Statements

Coast Salish artist Luke Marston was commissioned by the TRC to design and carve a bentwood box as a symbol of the ceremonial transfer of knowledge that took place at the TRC’s national events. In its final report, the commission described the box and how it was used:

The box was steamed and bent in the traditional way from a single piece of western red cedar. Its intricately carved and beautifully painted wood panels represent First Nations, Inuit, and Métis cultures. […] This ceremonial box travelled with the Commission to every one of its seven National Events, where offerings – public expressions of reconciliation – were made by governments, churches and other faith communities, educational institutions, the business sector, municipalities, youth groups, and various other groups and organizations. (TRC, 2015a, pp. 164-165)

Project of Heart

Ottawa teacher Sylvia Smith created Project of Heart, an art-based education initiative to teach children about the history of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, in 2008 as a response to the lack of knowledge about residential schools in the Ontario education system. It was chosen as a national commemoration project by the TRC in 2012-13. Over that year, schools across the country, as well as other community, church, and government organizations, learned about Indigenous history and created commemorative tiles and works to remember and honour residential school victims and survivors. In total, 55,000 students and 185,000 people across Canada participated in the Project of Heart, and the works they produced were “collected and curated into memorial and commemoration exhibits honouring former students of Indian Residential Schools in every province and territory in Canada” (“Virtual Tour,” 2008).

The TRC recognized the importance of this work in their final report:

By bearing witness, the project enables participants to transform empathy into action and solidarity on social justice issues affecting the lives of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis across the country. (TRC, 2015a, pp. 123-124)

Honesty: Education for Reconciliation

“Educating the heart as well as the mind helps young people to become critical thinkers who are also engaged, compassionate citizens” (TRC, 2015a, pp. 123-124). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission approached education as a key part of reconciliation, noting that non-Indigenous Canadians are largely unaware of how the problems faced by Indigenous communities developed. It believed the failure of the education system to teach this history was a large contributing factor to the current state of affairs (TRC, 2015a, pp. 117-118).

In the Commission’s view, all students—Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal—need to learn that the history of Canada did not begin with the arrival of Jacques Cartier on the banks of the St. Lawrence River… (TRC, 2015a, p. 119)

The commission went on to call upon the education system to make Indigenous history visible and present in its classrooms. To teach students about the “rich linguistic and cultural heritage” of the Indigenous Nations the Europeans encountered. To recognize Indigenous perspectives on that first contact that have been ignored in the history books. To teach the history of treaties so that students know that Indigenous Peoples negotiated “with integrity and in good faith” and can start to understand why Indigenous leaders still fight so hard to defend these agreements (TRC, 2015a, p. 119). The commission believed that such understanding would give Canadians a fresh view on the lack of respect for treaties and agreements shown by European settler governments and contribute to establishing the groundwork for true reconciliation (TRC, 2015a, p. 119)

References

Bouchard, D. (2009). The seven sacred teachings of White Buffalo Calf Woman. Vancouver, BC: More Than Words Publishers.

Brake, J. (2017, November 24). Labrador preparing for long overdue apology. APTN. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2017/11/24/labrador-preparing-for-long-overdue-apology/

Canadian Press. (2017, November 24). Trudeau apologizes to Newfoundland residential school survivors left out of 2008 apology, compensation. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2017/11/24/trudeau-to-apologize-to-newfoundland-residential-school-survivors-left-out-of-2008-apology-compensation.html

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2012). Discover Canada: The rights and responsibilities of citizenship [Study guide]. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/pub/discover.pdf

Fortune, L. (2018, April). Personal communication.

Guide to acknowledging First Peoples and traditional territory. (n.d.). Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT). Retrieved from https://www.caut.ca/content/guide-acknowledging-first-peoples-traditional-territory

Hooks, B. (2000). All about love: New visions. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Kohut, T. (2017, May 29). Pope’s apology for residential schools key step for reconciliation: survivor. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/3486599/pope-residential-school-apology/

Marche. S. (2017, September 7). Canada’s impossible acknowledgement. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/canadas-impossible-acknowledgment

Marie Wilson. (n.d.). Pierre Eliiott Trudeau Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.trudeaufoundation.ca/en/community/marie-wilson

Opening Ceremony. (2017). North American Indigenous Games 2017 (NAIG). Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/culture/opening-ceremony

Parrott, Z. (2014, July 10). Government apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/government-apology-to-former-students-of-indian-residential-schools/

Q&A with TRC Bentwood Box artist Luke Marston. (2017, January 26). UM News. Retrieved from http://news.umanitoba.ca/qa-with-trc-bentwood-box-artist-luke-marston/

Reconciliation. (n.d.). In English Oxford Living Dictionaries. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/reconciliation

Sandals, L. (2013, November 14). Art, residential schools & reconciliation: Important questions. Canadian Art Online. Retrieved from http://canadianart.ca/features/art-and-reconciliation/

Schwartz, D. (2015, June 2). Truth and Reconciliation Commission: By the numbers. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/truth-and-reconciliation-commission-by-the-numbers-1.3096185

Senator Murray Sinclair. (n.d.). Senate of Canada. Retrieved from https://sencanada.ca/en/senators/sinclair-murray/

Toronto District School Board (TDSB). (n.d.). Untitled document on treaty acknowledgements. Retrieved from http://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/Elementary/Treaty%20AcknowledgementFINAL.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.-a). Media room: TRC logo. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=14

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.-b). Meet the commissioners. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=5

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.-c). Reconciliation … towards a new relationship. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/reconciliation/index.php?p=331

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.-d). Share your truth. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=807

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2009, June 10). Appointment of new chairperson and commissioners of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission [News release]. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=40

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015a). Canada’s residential schools: Reconciliation: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Vol. 6). Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015b). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015c). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Retrieved from www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Virtual tour. (2008). Project of Heart. Retrieved from http://projectofheart.ca/

Wilton Littlechild. (n.d.). Speak Truth to Power Canada. Retrieved from http://sttpcanada.ctf-fce.ca/lessons/wilton-littlechild/bio/

Media (in order of appearance)

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (n.d.). [Logo for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission]. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=3

Enberg, S. (Photographer). (n.d.). TRC Banner: Walk for Reconciliation [Digital image].

Commissioners Chief Wilton Littlechild, Justice Murray Sinclair and Marie Wilson [Digital image]. (2013, January 28). Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/residential-school-hearings-start-in-fort-albany-1.1365718

[Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada]. (2011, June 20). Michaëlle Jean Welcomes Honorary Witnesses. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/25349505

Kilpatrick, S. [photographer]. (2015). Residential school survivor Lorna Standingready is comforted by a fellow survivor in the audience during the closing ceremony of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Wednesday, June 3, 2015[Digital image]. Retrieved from https://i.cbc.ca/1.3365371.1464898173!/cpImage/httpImage/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/16x9_780/truth-and-reconciliation.jpg

Centennial College. (2018). Rhiannon Johnson, Indigenous journalist [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/robR4Mb2DoA

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologizes on behalf of the Government of Canada to former students of the Newfoundland and Labrador residential schools [Digital image]. (2017). Retrieved from https://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2017/11/24/remarks-prime-minister-justin-trudeau-apologize-behalf-government-canada-former

Gerry Ambers’ Dzunukwa Dreaming of Summer Holidays, 1992, from the “Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools” exhibition (2009).

Child prisoners quilt [Digital image]. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.pimaatisiwin-quilts.com/uploads/2/4/8/1/24814779/2463595_orig.jpg

Bentwood box [digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://news.umanitoba.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Bentwood-Box_WEB.jpg

Tran, T. (Photographer). (2018). Centennial College student’s Project of Heart Tiles [Digital image].