21 Identity, Status, and Belonging

Status and Identity

A number of different terms are used by the federal government to describe Indigenous Peoples; for example, First Nations, Indigenous, Aboriginal, Métis, Inuit, Status Indian, Registered Indian, and non-status Indian. To learn more about the differences between these terms, please review the terminology section of this etextbook before you read this section on status and identity. Also note that these are not necessarily the terms that people use for themselves.

Indigenous Peoples represent 4.3 percent of Canada’s population: about 1.4 million people (Statistics Canada, 2016). Since 1876 the federal government has had an administrative system for tracking and registering what it calls “Status Indians,” but not all people who self-identify as First Nations or as Indigenous have status. For example, Métis and Inuit do not have status. This may change in the future, however, as recent Supreme Court decisions have ruled that Métis and Inuit are entitled to the same recognition as Status Indians – at the time of writing, the implications of the court decisions are still being debated (see The Canadian Press, 2014; Schertzer, 2016). Membership in a community or larger Indigenous organization (e.g., the Métis Nation of Ontario) is not dependent on whether one has status. About 1.9 percent of Canada’s population has recognized “Indian status”: approximately 638,000 people.

As Métis scholar Chelsea Vowel carefully lays out in her book Indigenous Writes, the government’s definition of who is and who is not an Indian has changed many times. Someone who fits the legal definition of being eligible for status today may not have been eligible if they’d been born in, say, 1950. Vowel (2016) writes that:

Not all status Indians are actually Indigenous (more on that in a bit), and there are many Indigenous peoples who do not have status. Status Indians are not the only Indians (First Nations) that exist. Non-status Indians are those who, through various pieces of legislation, lost their status, or were never eligible for status because their parents or grandparents lost status. Non-status Indians are still Indigenous; lack of status does not change this. (p. 27)

Indian Status

Gallery 5.1 Secure Certificate of Indian Status

The treaties section of this etextbook discusses how the First Nations who were already living in present-day Canada were moved off their traditional lands where they were harvesters and trappers, and onto small reserves. There, they were required to stay because, until the 1950s, the pass system was in effect, which meant that First Nations Peoples in reserve communities were not allowed to leave without a pass from the authorities.

Indian status was created at the same time as the reserve system. The government needed to track Status Indians because it had signed treaties with them and had a legal obligation to uphold the terms of what was signed. At the time of its creation under the Indian Act, Indian status was given to those from the First Nations who had signed treaties and was passed on to their descendants (children). Since then, other ways to acquire Indian status have been introduced, such as through marriage – see the section on Categories of Status for more information.

Many within and outside of Indigenous communities view Indian status as an insidious means of achieving the complete assimilation of First Peoples. The Indian Act of 1876 and the mechanism of status were initiated with the hopes that “Indians” would eventually become “civilized” if they didn’t die first from their susceptibility to Western diseases and lack of proper nourishment. The government also anticipated that the people left would be easily “enfranchised,” stripped of their registered status, and brought into the fold: they would have little or no future as Indigenous Peoples.

There are only a few ways to get status, and the vast majority of people have it because it was passed down from their biological parents. However, for many decades, there were numerous ways that people could lose their status. This used to be called “enfranchisement” because not only did it mean losing treaty rights (NOT free taxes, but the right to live on a reserve, for example), it also meant gaining the full citizenship rights that non-Indigenous Canadians enjoyed. For example, the Indigenous right to vote was not recognized until 1960. Until 1960, if a First Nations person wanted to vote, they had to give up their Indian status and become enfranchised.

Interactive 5.1 Colour Code: A podcast about race in Canada

On the first episode of Colour Code, Denise Balkissoon and Hannah Sung try to figure out Indian status: who gets it, what it means, where it came from, and how it resonates in Canada and Indigenous communities today.

Myths about the Benefits of Indian Status

In 2012 Canadian pop star Justin Bieber angered many within and outside of the Indigenous community when he said that he was “enough percent Indian or Inuit” to get free gas in Canada. He suffered a backlash from the community who quickly pointed out that he couldn’t be more wrong.

The myths circulating in Canada about tax exemptions, free housing, and free money flowing from the government to First Nations are damaging and completely inaccurate. The attention that is paid to this alleged issue continues to be massively disproportionate to the small affected population. The only Indian Act tax exemptions in Canada that are available to Status Indians are income tax and personal property tax ON reserve. As Chelsea Vowel (2016) lays out in her book Indigenous Writes, this applies to less than 300,000 people in Canada, 0.5 percent of the population, and yet the powerful national myth of Indians not paying taxes continues to be widespread. To be clear, the vast majority of Indigenous Peoples pay the same income, property, sales, and other taxes as non-Indigenous Canadians. Even those with Indian status who are eligible for tax exemptions on monies spent on reserve often pay taxes anyway because reserves can enact their own taxation systems and community members must contribute to these.

Categories of Status

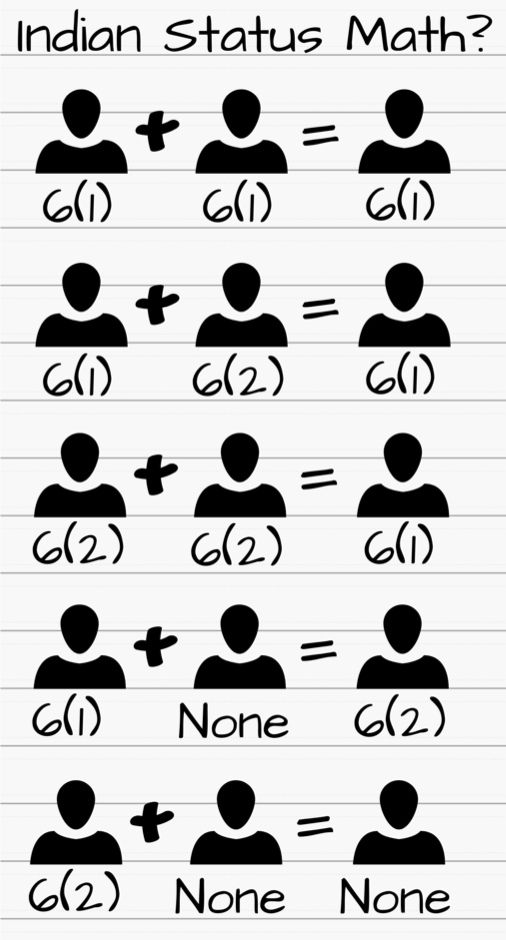

Indian status is based entirely on one’s ability to trace ancestry to First Nations communities that signed treaties. In other words, knowing and proving that one is Indigenous is not enough; Indigenous family members (parents and grandparents) need to have had Indian status, as it can only be acquired if it is passed down. In section 6 of the Indian Act, the government lays out two categories of status: 6(1) and 6(2). These are hierarchical categories, based on a number of criteria. Both categories confer full status (meaning they grant the same rights under treaty); they only differ in one major aspect: the ability to pass that Indian status down to children. See the formulas on the next page to understanding how these function more specifically. It is important to note that Canada does NOT use a blood quantum formula to determine status; this is a myth likely originating as a result of our proximity to the United States, which has different ways (including, in some cases, blood quantum) of determining band membership.

The categories of 6(1) and 6(2) most recently changed in 1985 due to Bill C-31; this amendment to the Indian Act came as a result of Indigenous Peoples arguing that since the repatriated 1982 Constitution included gender equality rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Indian Act needed to comply with these.

For over 100 years the Indian Act stipulated that any woman with Indian status who married a non-status man lost her status, and her children lost their ability to be registered for status. However, men who were Status Indians could marry whomever they chose (status or non-status women), and their wives and children were considered Status Indians. The amendment made the equation for status the same for men and women. As the accompanying chart shows, it only takes two generations of marrying out of the status system to completely lose the right to Indian status in Canada.

Identity

Identity and identity formation are complex processes for everyone, and our identities shift and change over the course of our lifetimes. For Indigenous Peoples, Indian status (or lack thereof) is only one part of identity. Indigenous identities are as complex and varied as the many Nations, cultures, languages, stories, and life experiences of the people. It is important to note that while Indigenous Peoples are diverse, they also share a common history in this country, shaped by the oppressive assimilationist policies of the past. Please refer to other sections of this etextbook, such as those on language, culture, traditions, and communities, to gain a better understanding of the many aspects that contribute to Indigenous identities.

Interactive 5.2 Derek Kenny, Anishinaabe artist

Derek Kenny discusses his identity and growing up in Anishinaabe communities.

References

Eells, J. (2012, August 2). Justin Bieber: Mannish boy. Rolling Stone. Retrieved from https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/justin-bieber-mannish-boy-the-2012-cover-story-20120802

Indian status. (n.d.). In Indigenous Foundations. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia. Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_status/

Joseph, B. (2012, November 2). Aboriginal veterans: Equals on the battlefields, but not at home. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Retrieved from https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/aboriginal-veterans

Justin Bieber chided by aboriginal group for free gas comment. (2012, August 3). CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/justin-bieber-chided-by-aboriginal-group-for-free-gas-comment-1.1193233

Romaniuc, A. (2000). Aboriginal Population in Canada: Growth dynamic under conditions of encounter of civilisations. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, XX(1), 95-137.

Schertzer, R. (2016, April 19). Schertzer: Here’s what the Supreme Court’s Métis ruling means [Opinion]. Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved from http://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/schertzer-heres-what-the-supreme-courts-metis-ruling-means

Statistics Canada. (2016, September 15). Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.cfm

The Canadian Press. (2014, April 18). Court of Appeal upholds landmark ruling on rights of Métis. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/court-of-appeal-upholds-landmark-ruling-on-rights-of-métis-1.2613834

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous writes: A guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit issues in Canada. Winnipeg, MB: HighWater Press.

Media (in order of appearance)

Topham, R. [photographer]. (n.d.). An Indian Shooting the Indian Act. [photograph]. Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, B.C. Retrieved from https://bombmagazine.org/articles/lawrence-paul-yuxweluptun/

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. (n.d.) Certificate of Indian Status Card [digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032424/1100100032428

Globe and Mail (producer). (n.d.). Colour Code: Race Card [podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/colour-code-podcast-race-in-canada/article31494658/

Centennial College. (2018). Derek Kenny, Anishnaabe artist [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/DL7WAvlXCrM