4 MMIWG

Introduction

At the time of writing this section of the etextbook, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (NIIMMIWG) is ongoing, and only the Interim Report has been published. The Inquiry has been plagued by many setbacks and challenges, both existential and logistical, which have significantly affected the speed and accuracy with which the commissioners have been able to examine the many truths and experiences at the heart of the Inquiry’s mandate. In light of these challenges, in March of 2018, the commissioners asked the federal government to extend the Inquiry for another two years with an additional $50 million in funding. This extension is intended to provide time for the Inquiry to hold more institutional and expert hearings as well as hear from vulnerable populations such as sex workers and the homeless. Commissioners believe this additional time will allow the Inquiry to more effectively meet the needs of the people it’s intended to serve. For our readers, this means that this is a living text that will grow and change as new information comes to light, until the many truths and outcomes of the Inquiry are woven into a clear dialogue which we can then share with you.

Roots of Violence Against Indigenous Women, Girls, LGBTQ, and Two-Spirit People

Indigenous women and Two-Spirit people on Turtle Island are sacred as they embody the roles of caregivers, creators, and knowledge keepers within their communities, both historically and in contemporary times. During and after colonization, these roles were directly undermined and dismissed by colonial and patriarchal authorities. The imposition of the Indian Act, the residential school system, and the Sixties Scoop contributed to the loss of identity and ways of knowing within Indigenous communities across Canada. These events generated profound and lasting intergenerational trauma, extensive experiences of violence, and the loss of self-worth experienced among Indigenous youth today. Dismissive attitudes towards this reality by colonial governments and settler populations have been magnified in the case of Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit people. The implications of this are far-reaching; in February 2016 activists for the Walk 4 Justice initiative listed the names of over 4000 women and girls who were missing or murdered; 60 to 70 percent of them were Indigenous (Tasker, 2016). The number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls continues to climb.

Defining Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls, and the LGBTQ2S Community

Violence against Indigenous women, girls, and the LGBTQ2S (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, queer, Two-Spirit) community has reached epidemic proportions in Canada today. Indigenous women report rates of violence 3.5 times higher than non-Indigenous women and girls, and incidence of death from violence occurs at rates five times higher (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (WHO, 2018, para. 1). This definition includes self-directed violence, interpersonal violence, and collective violence. The National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (2018b) expanded this definition to include cultural, colonial, and institutionalized violence, and reported that between 1997 and 2000 the rate of homicide for Indigenous women was seven times higher than the homicide rate of non-Indigenous women. Indigenous women and girls have been experiencing violence at rates unheard of for other demographics in Canada, and Indigenous communities have been demanding an inquiry into the loss of their women and girls for more than 20 years.

Interactive 1.13 Full story: The missing and the murdered

16×9 explores the troubling trend of violence against Indigenous women and hears from the families of the missing and murdered women and girls.

Interactive 1.14 CBC podcasts: Missing and murdered: Who killed Alberta Williams?

http://www.cbc.ca/missingandmurdered/podcast/ch1

In 1989, 24-year-old Alberta Williams was found dead along the Highway of Tears near Prince Rupert, BC. Police never caught her killer. Twenty-seven years later, her unsolved murder continues to haunt her family — and the retired cop who says he knows who did it.

Click the link image for the first podcast episode and slideshow produced by CBC News.

Estimates of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

No one knows for sure the exact number of women, girls, and LGBTQ2S people who have gone missing or been murdered in Canada (NIIMMIWG, 2018a). The RCMP national overview estimated the number to be 1200 in 2014, which is vastly different from the Walk 4 Justice initiative’s number of 4232 (RCMP, 2017; Tasker, 2016). The significant gap between these and other estimates is of concern. Commissioners of the Inquiry, as well as activists and Indigenous community members, point to the different methodologies used by police services in Canada to define/identify a murdered or missing Indigenous individual as the source of this discrepancy (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). This lack of consistency leads to challenges with statistics, identification, data, and reporting of incidences of violence. Many believe the number who have been murdered or disappeared is far higher than suspected (Kirkup, 2017; NIIMMIWG, 2018b). In Canada today, Indigenous women account for 4 percent of the female population and 24 percent of female homicides (Statistics Canada, 2015). This is hardly new: Indigenous women and girls have been going missing and being murdered since first contact with Europeans, although the epidemic only started to receive attention from non-Indigenous Canadians in the last 60 years, starting with some well-known cases in the 1950s (Red Power Media, 2016).

In June of 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its 94 calls to action. Call to action 41 requested a public inquiry into the cause of the disproportionate number of missing and murdered women and girls. This call to action also acknowledged the need for remedies that would not only address the increasing number of missing and murdered but help bring an end to the victimization of Indigenous women and girls in Canada (TRC, 2015).

Interactive 1.15 The REDress Project

http://www.theredressproject.org/

Jamie Black addresses the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women through installations of red dresses that act as visual reminders of the alarming number of women and girls who have gone missing or been murdered.

Click the link above to visit the website and learn more about the project.

National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls

On December 8, 2015, after many years of advocacy and pressure by Indigenous women, families, communities, grassroots organizations, and concerned public, the Canadian government announced an independent national inquiry into the increasing number of murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit people in Canada. The Inquiry, now in its second phase, is a long-awaited response to targeted activism by Indigenous Peoples who are tired of losing their loved ones, their sacred women and girls, and have demanded that their cries for support be heard.

The vision of the National Inquiry is to “build a foundation that allows Indigenous women and girls to reclaim their power and place” and to shed light on the epidemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls, and LGBTQ2S individuals (NIIMMIWG, 2018b, p. 4). The mission is threefold: “to find the truth,” to “honour the truth,” and to “give life to the truth” (NIIMMIWG, 2018b, p. 5-7).

On August 3, 2016, five commissioners were appointed to lead the Inquiry: Chief Commissioner Marion Buller; Commissioner Michelle Audette; Commissioner Brian Eyolfson; Commissioner Qajaq Robinson; and Commissioner Marilyn Poitras (NIIMMIWG, 2018c).

The Inquiry, though well-intentioned in its goals and mandate, quickly became plagued with setbacks related to its guiding framework and philosophy. In July of 2017 Marilyn Poitras resigned, citing concerns with the “current structure” of the National Inquiry (CBC News, 2017). Designed around a western legal framework, the Inquiry uses a commission model, which depends on hearings to find the truth rather than a community-based process (CBC News, 2017; NIIMMIWG, 2018b). Poitras believed that while this would ensure stories would be heard, it would not help the Inquiry get to the root of the problems driving the disproportionate number of MMIWG (CBC News, 2017).

Kinds of Violence Against Indigenous Women, Girls, and LGBTQ2S Communities

The National Inquiry’s Interim Report was unique in that it reviewed some critical pieces of literature and research that had previously attempted to understand the rates and experiences of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada. These reports included:

- The 1991 Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba

- The 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

- The 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Final Report

Collectively these reports served as a foundation for understanding the impacts of colonial violence on Indigenous communities in Canada. The National Inquiry aims to expand on this knowledge base and in the process contribute to a deeper understanding of violence against Indigenous women and girls and its roots in colonization (NIIMMIWG, 2018b).

The report also expressed that a review of previous reports as well as consultation with Indigenous communities affirmed that the end to this violence must be led by Indigenous Peoples, their communities, and their Nations (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). The National Inquiry recognized that this will require a profound and substantial change in the relationship between Canada and Indigenous Peoples. It further recognized that this violence is a direct result of colonization and that in order for violence against Indigenous women, girls, and LGBTQ2S to end, the colonial suppression fueling it also must end (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). To accomplish this goal, the National Inquiry confirmed it will apply an Indigenous lens to its work and consider the violence and the impacts of that violence from the perspectives of Inuit, Métis, and First Nations women, including girls, trans women, urban women, and rural women across Canada (NIIMMIWG, 2018b).

Scope, Power, Challenges, and Limitations of the National Inquiry

The National Inquiry, established under the Federal Inquiries Act, has conducted its investigation independently of the federal government (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). This gives the Inquiry the power to request documents, testimony, and items the commissioners feel are relevant to the Inquiry’s mandate. Each province and territory has its own public inquiry jurisdiction. This means that 13 independent inquiries are going on at the provincial and territorial levels at the same time as the National Inquiry in Canada (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). The presence of 14 legal inquiries allows for investigations on complicated issues that cross jurisdictional lines. This structure also enables the inquiries to be facilitated by one administrative body, which holds hearings and writes reports for all.

This model is not without its challenges. Before launching the Inquiry, the federal government invited people to provide their input into the process; it received responses from over 2000 people and more than 4000 online surveys, among other forms of data collection (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). This data, compiled in a report by the federal government, identified four key areas for focus: “Child and Family Services, law enforcement, criminal justice system and systemic issues and legacies” (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). However, the Inquiry, hoping to work independently of the federal government wherever possible, has not had an opportunity to conduct an independent analysis on this data due to challenges with accessing the computer software needed to complete the task efficiently. In the absence of this data, the commissioners have instead reviewed the pre-Inquiry community meeting data and used this material to help guide their overall research strategy (NIIMMIWG, 2018b).

During pre-Inquiry community meetings, Indigenous Peoples identified the impact of systemic racism, stereotypes, stigma, and racially motivated violence on their communities. They identified addictions issues, child welfare, poverty, family violence, gang involvement, human trafficking, organized crime, and lack of trauma supports for victims of MMIWG as areas in need of immediate attention (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). In addition, they cited “lack of trust in the justice system”; the role of police in perpetrating violence against Indigenous women and girls; fear of “retribution and bullying when reporting” crimes in their communities; and “the way the media depicts Indigenous women and victims of violence” as negative and stereotypical as other contributing factors to the violence experienced by Indigenous women and girls (NIIMMIWG, 2018b, p. 30). This data suggests the issues are far more extensive and complex than the federal government presented in its summary of four key areas of focus.

Beyond this, many practical challenges plague the administration of the Inquiry’s day-to-day operations (Macdonald & Campbell, 2017).

While the pre-Inquiry process is still being scrutinized, investigators, commissioners, the public, victims, survivors, and their families believe that the violence against Indigenous women and girls can only be understood when framed within the larger context of colonialism in Canada.

Interactive 1.16 Muskrat Magazine: Interview with Christi Belcourt

Rebeka Tabobondung interviews Christi Belcourt for MUSKRAT Magazine about the Walking with Our Sisters exhibition/memorial hosted by G’zaagin Art Gallery at the Parry Sound Museum. The exhibition ran from January 10 to 26, 2014.

Ending Violence; and Hopes for the Final Report

The Interim Report of the National Inquiry into MMIWG outlined recommendations taken from the three reports previously discussed, the pre-Inquiry community meeting process, and the federal data compilation. These were presented as preliminary recommendations meant to outline broader systemic factors that must be addressed to end violence against Indigenous women and girls.

To improve matters, the Inquiry commissioners were adamant that political jurisdictions in Canada (provincial, federal, and territorial governments) must learn to work together more cohesively, and in collaboration and coordination with Indigenous governments. This inter-jurisdictional cooperation is essential to a productive outcome for the Inquiry and to fully implement the preliminary recommendations identified as action steps to combat violence against Indigenous women and girls. Over the next two years, the Inquiry will attempt to implement this jurisdictional cooperation while participating in community hearings (with Indigenous communities), institutional hearings (with Indigenous organizations), and expert hearings on the systemic causes of violence against Indigenous women (NIIMMIWG, 2018b). The hope is that this research and truth gathering will lead to the publication of a final report that will outline the systemic causes of the MMIWG, as well as lead to the establishment of policy and practices aimed at reducing violence and increasing safety. The final report will also make recommendations for actions to address systemic causes of violence, while providing ways to honour and commemorate missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada (NIIMMIWG, 2018b, p. 79).

Interactive 1.17 APTN Investigates: After the stories are told

As the first phase of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) winds down, its future is still uncertain.

References

Aiello, R. (2017, November 1). A police task force, and more funding: Highlights of the national inquiry interim report. CTV News. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/a-police-task-force-and-more-funding-highlights-of-the-national-inquiry-interim-report-1.3659086

APTN News. (2018, January 11). Executive director of MMIWG inquiry stepping down. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2018/01/11/executive-director-mmiwg-inquiry-stepping/

Assembly of First Nations. (n.d.). Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and ending violence. Retrieved from http://www.afn.ca/policy-sectors/mmiwg-end-violence/

Butts, E. (2016). Robert Pickton case. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/robert-pickton-case/

CBC News. (2017, July 16). Q & A with Marilyn Poitras on why she resigned as MMIWG commissioner and her hopes for change. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/marilyn-poitras-mmiwg-commissioner-resign-q-a-1.4207199

CBC/Radio-Canada. (2016). Missing & murdered: The unsolved cases of Indigenous women and girls [Website]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/missingandmurdered/

Galloway, G. (2018, March 6). National Indigenous women’s inquiry seeks additional time to complete its work. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/missing-and-murdered-inquiry-asks-for-two-more-years-to-do-its-work/article38218143/

Kirkup, K. (2017, November 1). Missing, murdered inquiry calls for creation of national police task force. CTV News. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/missing-murdered-inquiry-calls-for-creation-of-national-police-task-force-1.3658376

Macdonald, N., & Campbell, M. (2017, September 13). Lost and broken. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/lost-and-broken/

MacLean, C. (2018, February 22). Jury finds Raymond Cormier not guilty in death of Tina Fontaine. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/raymond-cormier-trial-verdict-tina-fontaine-1.4542319

Martens, K. (2018, March 7). MMIWG inquiry asks for a two-year extension and $50M more. APTN News. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2018/03/07/90860/

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2018a). Home page. Retrieved from http://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2018b). National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Interim Report [PDF]. pp. 1-113. Retrieved from http://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/en/interim-report/

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2018c). Meet the commissioners. Retrieved from http://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/meet-the-commissioners/

Native Women’s Association of Canada. (2017). National Inquiry into MMIWG: Understanding MMIWG. Retrieved from https://www.nwac.ca/national-inquiry-mmiwg/understanding-mmiwg/

Pember, M. A. (2017, August 2). Canada MMIW Inquiry struggles as staff flee. Indian Country Media. Retrieved from https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/first-nations/canada-mmiw-inquiry-struggles/

Red Power Media. (2016, July 18). Drag the Red sets out on new boat to search fast-moving waters. Retrieved from https://redpowermedia.wordpress.com/tag/drag-the-red/

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. (2017). Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Retrieved from http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/aboriginal-autochtone/mmaw-fada-eng.htm

Sabo, D. (2016). Highway of Tears. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/highway-of-tears/

Smiley, M. (Director). (2015). Highway of Tears [Documentary]. Retrieved from https://highwayoftearsfilm.com/watch

Tasker, J. P. (2016, February 16). Confusion reigns over number of missing murdered Indigenous women. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/mmiw-4000-hajdu-1.3450237

The Canadian Press. (2018). Native Women’s Association ‘outraged’ by upheaval at MMIW inquiry. CTV News. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/native-women-s-association-outraged-by-upheaval-at-mmiw-inquiry-1.3757120

The Canadian Press. (2014, May 12). ‘Women are still going missing’: Despite assurances, no progress on B.C.’s infamous Highway of Tears. National Post. Retrieved from http://nationalpost.com/news/canada/women-are-still-going-missing-despite-assurances-no-progress-on-b-c-s-infamous-highway-of-tears

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). 94 calls to action [PDF]. Retrieved from www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

World Health Organization. (2018). Definition and typology of violence. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition/en/

Media (in order of appearance)

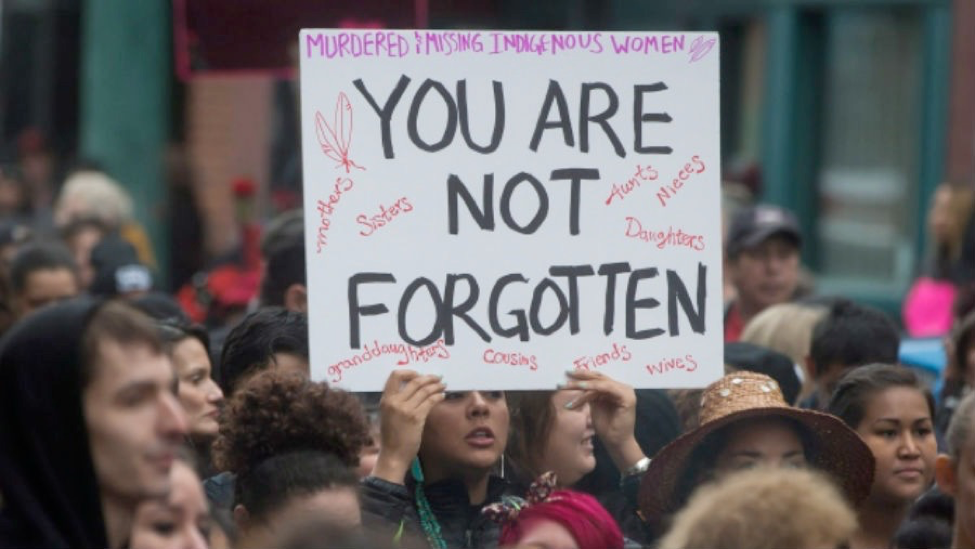

Woman Holds Up “You Are Not Forgotten” sign [photograph]. (2015, February 14). Retrieved from https://www.nationalobserver.com/2015/12/08/opinion/former-detective-applauds-inquiry-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women

[Global News]. (2015, March 7). Full Story: The missing and the murdered. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YcKKJ2kkvuc

CBC (producer). (2016) Who Killed Alberta Williams?. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/missingandmurdered/podcast

Winterstein, S. (Photographer). (n.d.). Centennial College student participation in Faceless Dolls Project [Digital image].

[Muskrat Magazine]. (2014, March 14). MM interview with Metis artist Christi Belcourt on Walking with our Sisters WWOS. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehyOa05ecNA

[APTN News]. (2018, May 7). After the Stories Are Told | APTN Investigates. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tyM3g_SYtA