2 Lost Generations

Introduction

The phrases “Sixties Scoop” and “Millennial Scoop” are used to describe two periods of time during which Indigenous children were brought into the child welfare system en masse and in disproportionate numbers to other ethnicities in Canada.

From the late 1950s to the early 1980s, a large number of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children were removed from their

families and communities and adopted into non-Indigenous homes. This has come to be known as the Sixties Scoop, and the children who were taken are often referred to as the Stolen or Lost Generations. The Millennial Scoop was coined to describe the alarming rate at which Indigenous children continue to be brought into the child welfare system and spans the early 1980s to today.

Interactive 1.7 The Sixties Scoop explained

CBC The National summary of the Sixties Scoop (2016).

Sixties Scoop: Setting the Stage

After World War II the federal government began to assume control of the residential schools from churches, which had previously been contracted to run them (Mackenzie, Varcoe, Browne, & Day, 2016, p. 2). The Indian Residential Schools rarely (if ever) provided curriculum to Indigenous youth on par with that provided in other education systems in the country; the goal of residential schools was not to provide academic skills, but rather to ensure assimilation into the dominant Euro-Western Christian culture (Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 4). It was often assumed that Indigenous students were incapable of understanding academically rigorous programming, and curriculum tended to focus on religious teachings and manual labour skills. As residential schools transitioned from Christian-run institutions to federal agencies, many of them became de facto child protection centres (Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 4).

As this transition was taking place, social services were growing across Canada. The Canadian Welfare Council and the Canadian Association of Social Workers submitted a proposal to amend the Indian Act to extend power to the provinces to deliver health care, welfare, and education services to on-reserve communities (Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 6). In 1951 this amendment – Section 88 of the Indian Act – was accepted with little consideration for how it would impact Indigenous families living on reserves (Sinha & Kozlowski, 2013, p. 3; Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 6). The transfer of responsibility from federal to provincial governments was formalized with the transfer of federal funding for child protection services to the provinces in the Canada Assistance Plan in 1966 (Sinclair, 2016, p. 9).

In the years that followed the amendment, each province and territory established its own structure for providing child welfare services to on-reserve communities. The lack of a formal national policy or structure meant that each province was tasked with designing its own policies and processes without federal or community input. It was a recipe for disaster. In British Columbia, the children’s aid societies established an informal agreement to provide child protection and foster care services to Indigenous communities in the province; however, there was no provincial agreement to provide preventative services, such as daycare, often crucial to ensuring families remained united (Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 6). As a result, within a span of 10 years, Indigenous children went from being basically unrepresented in foster care to making up one-third of the foster-care population in British Columbia; other provinces experienced a similar shift (Vowel, 2016, p. 181).

Scooping the Children

By the early 1960s there was a significant uptick in the number of child welfare cases involving Indigenous children that resulted in adoption. Many of the children involved were adopted without the knowledge of their families or bands (Sinclair, 2007, p. 66). During this time most adoptions were transracial, meaning a child of one ethnic group is adopted by a family of another ethnic group. For Indigenous children this meant that the majority were adopted into middle-class white Christian families. In this way the child welfare system continued the work of the residential school system, and many have come to see these adoptions as a further example of ethnic cleansing in Canada (Sinclair, 2007, p. 69).

The number of Indigenous children apprehended and adopted during this time was far higher than the national average for other ethnic groups (Sinclair, 2007, p. 66). Many of these children were transracially adopted within Canada; others were sold to the United States and overseas (Mackenzie et al., 2016, p. 7). It is estimated that 11,132 children with Indian status were placed in the child protection system; the number including non-status and Métis children was roughly 20,000 (Vowel, 2016, p. 182). Reports estimate that nearly one-third of all Indigenous children in Canada were separated from their families by adoption during this time period (Sinclair, 2007, p. 66). Of those adopted, 70 to 90 percent were placed with non-Indigenous families (Vowel, 2016, p. 182).

Interactive 1.8 Rob Lackie on the Sixties Scoop

Rob Lackie shares his personal story about the Sixties Scoop and the impacts on his family.

Resistance and Changes in the Child Welfare System

The 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of resistance movements like the National Indian Brotherhood (NIB) that raised concerns and advocated to change the systems that affected Indigenous communities. NIB, while advocating for control of First Nations education, also took aim at the child welfare system and argued for the need for change and for Nations to have an increased voice in the system (Sinclair, 2007, p. 68).

That was slowly happening in Canada. In the early 1980s child welfare agencies operated by First Nations communities began to emerge and quickly flourished. In 1981 there were four; by 1986 there were 30 (Sinha & Kozlowski, 2013, p. 4). However, a federal moratorium on recognizing new agencies, along with strict funding controls, soon impeded the creation of new agencies (Sinha & Kozlowski, 2013, p. 4).

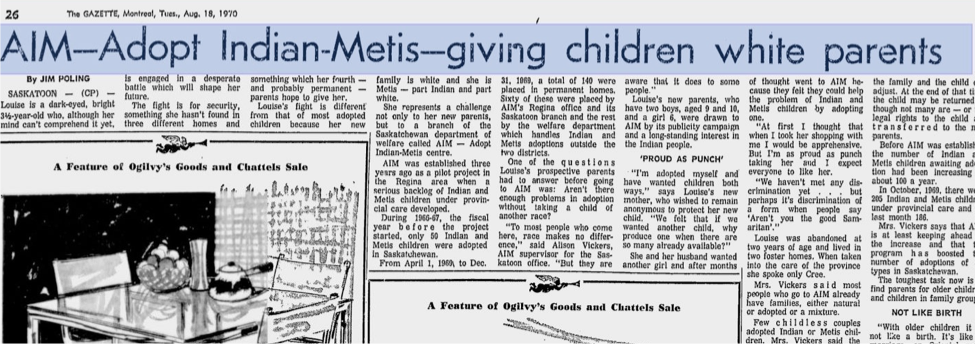

Gallery 1.9 Adopt Indian and Métis (AIM) newspaper ads

The United States, which had also implemented segregated school systems, reservations, and transracial adoption policies, passed the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978. This legislation prevented transracial adoptions of Native American children without the consent of their band (Sinclair, 2007, p. 68).

Canada’s response to the activist work of the NIB and the new US polices included commissioning Patrick Johnston’s 1983 report Aboriginal Children and the Child Welfare System, where the term “Sixties Scoop” first appeared in academic literature (Sinclair, 2007, p. 69). Justice Edwin Kimelman led a judicial review of Aboriginal adoption in the province of Manitoba; his report The Quiet Place, more commonly known as the Kimelman Report among child protection agencies, placed a moratorium on Indigenous transracial adoptions in Canada (Sinclair, 2007, p. 68). This decision, while responding to serious concerns about the child welfare system, did not reduce the number of Indigenous children taken into care. It simply reduced the number of children eligible for adoption, resulting in the majority of Indigenous children being placed in long-term fostering programs (Sinclair, 2007, p. 68).

Interactive 1.9 Councillor Laura Colwell on the Sixties Scoop

Councillor Laura Colwell talks about her personal story and being part of the Sixties Scoop.

Interactive 1.10 Missing & Murdered: Finding Cleo

www.cbc.ca/i/caffeine/syndicate/?mediaId=1177983043687

Where is Cleo? Taken by child welfare workers in the 1970s and adopted in the US, the young Cree girl’s family says she was stolen, raped, and murdered while trying to hitchhike back home to Saskatchewan. Host Connie Walker joins their search.

Millennial Scoop: Best Interest of the Child

After the Kimelman Report was published in Manitoba, other provinces followed suit and began to seek the consent of families and bands when processing First Nations adoptions (Sinclair, 2016, p. 10). Provincial, not federal, acts govern the child and family services agencies in Canada; in 1985 both Manitoba and Ontario amended their Child and Family Services Acts to formally include a clause about the “best interest of the child.” This refers to the idea that all child welfare work should be guided by doing what is best for the child involved. This amendment included the requirement of agencies and courts to take into consideration the cultural, linguistic, racial, and religious backgrounds of children when providing services and placing them in foster or adoptive homes (Sinclair, 2016, p. 11).

Children in Care

Despite some of these changes to the child welfare system, Indigenous children continued to be brought into care in numbers disproportionate to non-Indigenous children. By 2002 an estimated 22,500 Indigenous children were in the foster-care system – more than the number of children adopted during the Sixties Scoop and more than the number in residential schools at their height of enrollment (Vowel, 2016, p. 182). For a variety of reasons, Indigenous children are six to eight times more likely to end up involved with the child welfare system.

Neglect is the most common reason for the apprehension of Indigenous children. This risk factor is linked to poverty, inadequate housing, domestic violence, and substance misuse (Sinha & Kozlowski, 2013, p. 3; Vowel, 2016, p. 185). Intergenerational trauma, resulting from prior government policies such as residential schools and the Indian Act, is certainly a factor in how many Indigenous children suffer neglect and child welfare intervention.

The current child welfare system continues to face the struggles that contributed to the Sixties Scoop. Agencies working to provide services to First Nations communities are underfunded, receiving roughly 78 cents for services on-reserve for each dollar spent on services off-reserve (Vowel, 2016, p. 184). Often this financial barrier prevents agencies from providing services that may prevent apprehension or ensure reunification of families.

In 2007 the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society (FNCFCS) with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) filed a human rights complaint against the Government of Canada in the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) for their continued discrimination against First Nations demonstrated through the persistent underfunding of their child welfare services. Initially the CHRT dismissed the case; however, under judicial review, the Federal Court of Canada ordered it to hear the matter. After 72 days of hearings between 2013 and 2014, the CHRT substantiated all claims made by FNCFCS and ordered Canada to immediately stop the discriminatory behaviour (FNCFCS, 2016). In February 2018, after nearly two years of inaction on the part of the government, the CHRT again ordered the Government of Canada to comply with its 2016 decision, something Indigenous Service Minister Jane Philpot has committed to – with retroactive payments to the date of the decision.

Adoption

In 1994 the United States implemented the Multi-Ethnic Placement Act (MEPA) and in 1996 the Removal of Barriers to Interethnic Adoption (IEP). This policy and amendment operate on the notion that transracial adoption is better than long-term foster care. Canada does not have legislation that parallels MEPA-IEP; however, in a 2005 Saskatchewan court decision, Justice Jacelyn Ryan-Froslie ruled that denying an adoption based on race was unconstitutional (Sinclair, 2007, p. 69).

Increasingly, adoption cases involving Indigenous children who are placed into non-Indigenous family homes have relied on a single case: Racine v. Woods (1983). In this case Justice Berth Wilson ruled the bond between a child and their foster/prospective adoptive parent supersedes their cultural needs when considering the best interest of a child (Sinclair, 2016, p. 11). While this argument is unproven, the Canadian courts continue to show deference to foster/prospective adoptive parents over the cultural needs of Indigenous children. Many point to this pattern of non-Indigenous families adopting Indigenous children to be further demonstration of ethnic cleansing through the child welfare system.

Interactive 1.11 CBC Radio One: The Current

www.cbc.ca/i/caffeine/syndicate/?mediaId=1145734211958

www.cbc.ca/i/caffeine/syndicate/?mediaId=1145720899595

www.cbc.ca/i/caffeine/syndicate/?mediaId=1145732163693

The Millennium Scoop: Indigenous youth say care system repeats horrors of the past. Click to visit the CBC Radio One website and listen to three youth share their stories.

Apology and Class Action Lawsuit

Apology

In June 2015 Greg Selinger, premier of Manitoba, was the first government official to apologize for the Sixties Scoop, saying, “It was a practice that has left intergenerational scars and cultural loss. With these words of apology and regret, I hope all Canadians will join me in recognizing this historic injustice. I hope they will join me in acknowledging the pain and suffering of the thousands of children who were taken from their homes” (as cited in Hoye, 2015, para. 3). The apology was groundbreaking, and for some, it seemed to signal a shift in how Canadians would understand the experience of so many Indigenous adoptees. For others, it was not enough as it did not address or seek to change a system that continues to disproportionately remove Indigenous children from their communities.

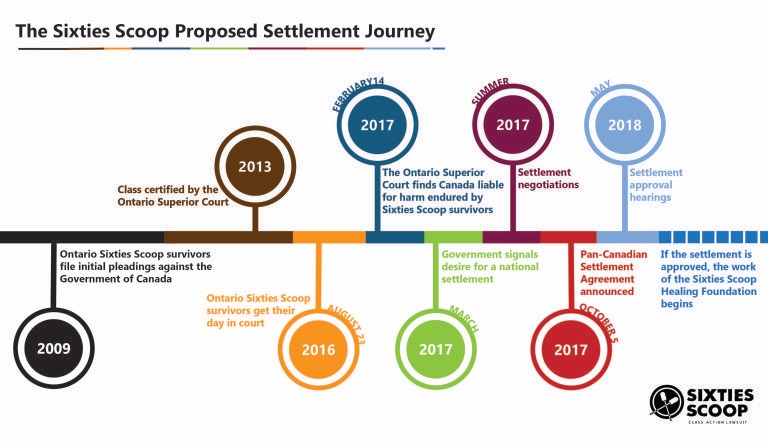

Class Action Lawsuit

The survivors of the Sixties Scoop have sought justice and recognition over the past few decades, most notably with the recently settled class action lawsuit that aimed to provide some measure of restitution to those who were removed from their families between 1951 and 1991, and as a result, lost their cultural identities and ties to their communities of origin. It is anticipated that individual claimants will receive at least $25,000 as part of the settlement, and an additional $50 million that has been earmarked to create a healing fund.

Interactive 1.12 Ontario Sixties Scoop: Q&A about the Sixties Scoop settlement

Kenn Richard, executive director, Native Child and Family Services of Toronto, sat down with Raven Sinclair, a Sixties Scoop adoptee, and Jeffrey Wilson, lead counsel on the Ontario Sixties Scoop class action lawsuit, for an open and honest conversation regarding the Sixties Scoop settlement.

References

First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. (2016). Canadian Human Rights Tribunal Decisions on First Nations Child Welfare and Jordan’s Principle (Case Reference CHRT 1340/7008). Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Info%20sheet%20Oct%2031.pdf

Hanson, E. (2009). Sixties Scoop. In Indigenous Foundations. University of British Columbia. Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/sixties-scoop.html

Hoye, B. (2015, June 17). Manitoba Premier Greg Selinger apologizes for Sixties Scoop. CBC. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/manitoba-premier-greg-selinger-apologizes-for-sixties-scoop-1.3118049

Leung, C. (2014, October 12). “Sixties Scoop”. Retrieved June 14, 2018, from http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/timeline/543a2904d2e5248e40000014

McKenzie, H. A., Varcoe, C., Browne, A. J., & Day, L. (2016). Disrupting the continuities among residential schools, the sixties scoop, and child welfare: An analysis of colonial and neocolonial discourses. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(2). Retrieved from http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=?url=https://search-proquest-com.eztest.ocls.ca/docview/1858127786?accountid=39331

Sinclair, R. (2007). Identity lost and found: Lessons from the sixties scoop. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(1), 66-82. Retrieved from http://journals.sfu.ca/fpcfr/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/25

— (2016). The Indigenous child removal system in Canada: An examination of legal decision-making and racial bias. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 11(2), 9-18. Retrieved from http://journals.sfu.ca/fpcfr/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/310

Sinha, V., & Kozlowski, A. (2013). The structure of aboriginal child welfare in Canada. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 4(2). Retrieved from http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=?url=https://search-proquest-com.eztest.ocls.ca/docview/1400220610?accountid=39331

Sixties Scoop Class Action Lawsuit. (2018, May 14). About the Ontario Sixties Scoop Claim + The National Settlement. Retrieved from https://sixtiesscoopclaim.com/about-the-ontario-sixties-scoop-claim-registration-as-a-class-member/

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous writes: A guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. Winnipeg, Manitoba: HighWater Press.

Media (in order of appearance)

Adopt Indian and Metis Project. (n.d.) [Adopt Indian and Metis Project print advertisements]. Retrieved from http://activehistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/12.png

[CBC News]. (2016, September 29). The Sixties Scoop Explained. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PvnAroiZuk

Aim Centre. (1972, November 14). [Advertisement for Arthur]. Regina Leader-Post. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/creator-of-sixties-scoop-adoption-program-says-it-wasn-t-meant-to-place-kids-with-white-families-1.4584342

Adopt Indian and Metis Project. (n.d.) [Adopt Indian and Metis Project print advertisements]. Retrieved from http://activehistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/12.png

Centennial College. (2018). Rob Lackie on the 60s scoop [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/IeKwv-fHvf4

Aim Centre. (1972, October 31). [Advertisement for Gwen]. Regina Leader-Post. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/creator-of-sixties-scoop-adoption-program-says-it-wasn-t-meant-to-place-kids-with-white-families-1.4584342

Centennial College. (2018). Councillor Laura Colwell on the 60s scoop [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/2K9rZbXvl04

CBC (producer). (n.d.) Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/radio/podcasts/missing-murdered-who-killed-alberta-williams/

CBC: The Current (producer). (2018, January 25) The Millennium Scoop: Indigenous youth say care system repeats horrors of the past [radio broadcast]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/a-special-edition-of-the-current-for-january-25-2018-1.4503172/the-millennium-scoop-indigenous-youth-say-care-system-repeats-horrors-of-the-past-1.4503179

[Ontario60sScoop]. (2018, April 14). Q&A About the Sixties Scoop Settlement. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqtTt1V0CeA

Sixties Scoop Proposed Settlement Jouney [digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://sixtiesscoopclaim.com/