33 Land Claims, Title, and Ownership

Land Is Central to Indigenous Peoples

For Indigenous Peoples, land is central to every aspect of life. Indigenous Peoples’ lives and cultures are derived from the land they live on – this influences their diet, cultural practices, ceremonies, spiritual beliefs, housing structures, patterns of land usage, and relationships with the animals and plants sharing that land. While Indigenous Peoples have diverse cultures, they all share a foundational connection to the land. The private ownership of land (as part of a larger system of wealth accumulation) is not an Indigenous concept; in other words, the idea that land can be owned, monetized, bought, and sold is an idea that arrived with the settlers of Turtle Island. Indigenous Peoples understand that without a balanced relationship with their environment, their very existence is at risk. In the pre-contact period, land on Turtle Island was shared. Geographical boundaries, like the Rocky Mountains, the Great Plains, and the Great Lakes, acted as border zones between Indigenous Nations. For example, before the arrival of Europeans, the Anishinabek (or Ojibwe) Nation lived north of the Great Lakes, and the Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois) Nation lived on the south side of the Great Lakes. People thought of themselves as caretakers or stewards of the land, rather than private owners of clearly defined areas.

Gallery 6.26 Archeological findings demonstrating long history of Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island

Hakai area, Calvert Island, British Columbia (central coast)

The Hakai region of coastal BC is made up of many islands, and First Nations, especially the Hieltsuk Nation (a.k.a. Bella Bella), have lived in this area for millennia. The Hakai Institute has found evidence of human activity in the area that goes back over 10,000 years, which confirms the oral history of the Hieltsuk community. This community was devastated by disease after contact with Europeans, and the community’s numbers dropped dramatically in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but it remains present in its original territories today.

The Bluefish Caves, Yukon

“This horse mandible, found in Yukon’s Bluefish Caves, appears to be marked by traces of stone tools. It might prove that humans came to North America 10,000 years earlier than previously believed” (Lauriane Bourgeon, quoted in Pringle, 2017).

In the 1970s French-Canadian archaeologist Jacques Cinq-Mars found 24,000-year-old remains of wooly mammoths and extinct horse breeds at this site. The bones showed evidence of butchering and toolmaking, but this ran against the thinking of the time, which was that people had first arrived in North America around 13,000 years ago. Cinq-Mars was laughed at when he first presented his findings at academic conferences, but they are widely accepted today.

Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, Southeastern Alberta

This provincial park and national historic site in Blackfoot territory contains many petroglyphs (carvings done with bone or metal tools) and pictographs (drawings) that are up to 700 years old. Evidence of human activity in the area dates back over 3000 years. In Blackfoot, this place is called Áísínai’pi, which means “it is pictured.” There are more than 80 archaeological sites in the park, and researchers have found evidence of tipi rings, buffalo jumps, and campsites.

Wanuskewin, Northern Saskatchewan

One of the longest running archaeological sites in Canada, in the territories of the Northern Plains Nations. Evidence points to human occupation going back 6000 years. The site also includes a medicine wheel that is 1700 years old, evidence of the longevity of the culture of Northern Plains communities.

Sourisford Linear Burial Mounds, Manitoba

A national historic site consisting of some of the best preserved burial mounds in Canada, which date human activity in the area to 10,000 years ago.

Mnijikamind Fish Weirs, Ontario (near Orillia)

A place in the river used by Indigenous Peoples to catch fish using a trap made out of wooden poles strung with netting made from plants/vines.

Route 8 campsite, New Brunswick

Discovered next to a highway near Fredericton, on what would have been a beach along a former glacial lake, this extremely rare archaeological find is of a camping site, complete with a fire pit and ancient charcoal. More than 600 objects were recovered from the site, some dating to 12,700 years ago, including arrow- and spearheads, and stone tool fragments. Some of the tools are hewn from stone that originated as far away as Maine, demonstrating extensive trade and travel among groups along the East Coast.

Debert Paleo-Indian National Historic Site, Nova Scotia

Described as “the oldest known and best-recorded Palaeo-Indian site in Atlantic Canada”(Canadian History Museum, n.d.), it provides evidence of human occupation dating to at least 10,500-11,000 years ago. Artifacts recovered at the site reveal a people who hunted migrating caribou herds and quarried colourful, volcanic rock, prized for its sharp edges for making tools, sometimes from sites as far as 50 km away.

Jones site, St. Peter’s Bay, Prince Edward Island

Located on the northeast coast of the island, this archaeological site has revealed evidence of continuous human occupation for over 10,000 years. The strategic fishing location provided a bounty from rivers and the sea, and in addition to fishing and hunting land game, the inhabitants also hunted harbour and grey seals, and possibly walrus.

Pinware Hill, Strait of Belle Isle, Newfoundland

Up until 10,000-11,000 years ago, Newfoundland and Labrador were still covered in glacial ice, making them some of the last places in the hemisphere to be populated. Radiocarbon testing at this site, located on the Labrador Straits, has dated artifacts to almost 9000 years ago. Tools such as small spears, dart points, knives, and scrapers were made using the same methods used by other Maritime peoples, showing travel and trade among groups. Evidence has been found here of both land and sea mammal use.

Understanding the Legal Framework of Land in Canada

Differing conceptions about land has proved a major problem between settlers and Indigenous Peoples. For settlers, land is a commodity that can be owned and used to generate wealth (money). For Indigenous Peoples, land is necessary for survival and for thriving communities; by taking care of the land, resources, animals, plants, and water, they ensure their own long-term well-being.

Gaining a clear understanding how the kings and queens of Europe, and later, the nation state of Canada, came to call all of the land theirs is not easy. One problem is that while many legal agreements were made (in the form of treaties), the Government of Canada has often not honoured their terms and conditions. There are two categories of land claims in Canada: specific and comprehensive. Specific land claims deal with land for which a treaty was signed, meaning that the basis of the land claim is that the Canadian government did not fulfill some of the obligations laid out in the particular treaty. There are a number of court cases ongoing today that are trying to resolve conflicts over specific land claims. Comprehensive land claims involve land for which no treaties have been signed, but which have been part of traditional territories since time immemorial.

This section will look at the legal basis for Indigenous Peoples’ claim to land, which is often referred to as Aboriginal title. It will also describe how various treaties, court cases, and other policies have redefined how land is controlled in Canada.

The Legal Basis for Canada

How did Canada come to be recognized by the rest of the world as a nation, and how did it gain control of the land of Indigenous Peoples?

Canada’s creation came about in part due to power struggles going on in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. European nations established colonies all over the world in order to generate wealth and power; colonies were much like corporations – in fact, large swaths of North America (up to 15 percent of its total acreage) were held exclusively by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). At one time the largest private landowner in the world, it held a monopoly on using the land and resources for more than 200 years (Defalco & Dunn, 1972).In Europe, the idea of private property wasn’t always as ubiquitous (or common) as it is to us today. Before the seventeenth century, most land was for common usage, meaning it was shared for activities like farming. This changed with the enclosure movement, which saw these lands divided up and usage restricted to the owner.

Interactive 6.13 Chief Duke Peltier discusses unceded territory

Chief Duke Peltier, of Wikwemikong (Unceded) First Nation, discusses the meaning of unceded territory in his community.

Land Acquisition in Canada

There were two main ways that land went from being under Indigenous control to being claimed by the Canadian state (and then reallocated for private ownership or government use, i.e., municipal lands, Crown land, etc.). First, some land was simply taken without regard to law or existing rights – this land is considered unceded (see the section on Treaties). Second, land was turned over to the control of European colonizers through the signing of treaties between Indigenous Nations and the monarchies of Europe (especially Britain and France). Treaties are legal agreements upheld by international law, so these allowed Canada to claim the right to exist as a legal entity upon these lands. Some question, however, whether these treaties were valid given that their terms were often not upheld by the colonizing governments.

Lands Claims in Canada

The nation state of Canada uses a legal framework that records “ownership” of the land (which is to say legal control that can be backed up by the force of the national police or army if necessary). As far as the Government of Canada is concerned, all land inside the boundaries of the state is owned and under the control of either the Crown, private citizens, or corporations. Though Aboriginal title was recognized as early as 1763 (the Royal Proclamation) and re-affirmed in the 1982 Constitution, Indigenous rights to their lands were subordinate to those of the Crown (see St. Catherines Milling v. The Queen, 1888). The Crown considered Indigenous lands to be usufruct. This means that Indigenous lands could be occupied and used by the Crown (or whomever the Crown handed control to) as long as they were not altered or damaged. Although Indigenous Peoples had rights to the land under common law, they were limited and lesser than the rights owned by the monarch.

Sovereignty

Sovereignty means that within the borders of a place, the landowner controls what happens, and any wealth derived from the place is theirs. Sovereignty supports the establishment of an international order where countries respect each other’s claims to territory and confirm this in “common law” (a legal system they all agree to participate in). When Europeans “discovered” new lands overseas, they did not believe the concept of sovereignty applied to the people who already lived there. They only recognized the sovereignty of other Christian, European, and patriarchal nations. Instead they used concepts like the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius to support their conquests and justify claiming non-Christian lands at will.

Doctrine of Discovery

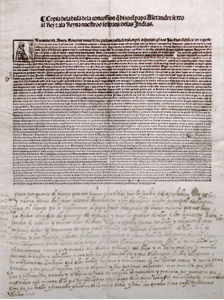

Under the decree of Pope Alexander VI, Spanish explorers were granted the authority to “discover” any lands that were not European and Christian. This gave Christopher Columbus free rein to colonize and indoctrinate the Indigenous Peoples of North America.

Based on the fifteenth-century concept of the Law of Christendom, the Doctrine of Discovery said that Christian explorers had the right to conquer and lay claim to territories unpopulated by other Christians. This meant that any and all lands and peoples “discovered” in Asia, Africa, and the Americas could be rightfully (justly) conquered and made subordinate to the European (Christian) nation. In a 2010 report on the topic, the UN found that the “legal construct known as the Doctrine of Discovery … has served as the foundation of the violation of their [Indigenous Peoples’] human rights” all over the world (Special Rapporteur, 2010).

Terra Nullius

Terra nullius is Latin for “nobody’s land” and the term was used to describe land where no Christians lived. This land was thought to be empty and could be seized by the Crown and reallocated as the Crown saw fit. No effort needed to be made to compensate or even acknowledge the existence or rights of the non-Christian people currently living on these lands.

The Western version of the history of Canada often refers to the land being conquered, ceded, sold, or given up by Indigenous Peoples, but many Indigenous Peoples assert a very different story about the loss of land. For example, they point out that treaty-signing processes were often deeply flawed because they took place under conditions that were coercive and unfair. This historical context is explained in more detail in the treaty section of this etextbook. While many Canadians believe strongly in the legal underpinnings of land ownership, it is important to acknowledge that the current state and division of land ownership in Canada today reflects some disturbing and antiquated ideas – like the idea that Christians are superior to other people and that lands of non-Christian peoples were free for the taking.

To reclaim their rights over their land, Indigenous Peoples rely on the notion of Aboriginal title. A lot of land was unceded (not covered by a treaty, and therefore never legally relinquished by the Indigenous Nations who were there before Canada was formed), and so Aboriginal title is key to (re)gaining legal recognition and control of the land.

Legal Categories of Land in Canada

Aboriginal Title

At the most basic level, all land was Indigenous land until it was ceded or taken. Aboriginal title is the legal category that confirms that Indigenous Peoples were here before Europeans and that they had ownership of the land until they relinquished it through treaties. The legal basis of Aboriginal title has been strengthened over time through a series of important court cases and legislation. These court cases and major legislation are briefly reviewed in this timeline.

Crown Land

Most of the land within Canada’s borders is not privately owned, nor held by Indigenous Peoples. The majority of land, about 90 percent, is either federal or provincial Crown land. The “Crown” refers to the King or Queen, but when Canada stopped being a British colony and became an independent country, the Crown’s control passed to the elected government. The Canadian government owns so much Crown land, most of it in the northern territories, that it is one of the largest landowners in the world. Overall in Canada, 11 percent of land is privately owned.

Fee Simple

Fee simple is the most common form of private property ownership in Canada. The average person who owns their home in Canada is a fee simple owner. This means that their ownership is recognized at the highest level in real estate law, although certain conditions apply; for example, they must comply with tax law and allow police jurisdiction over/on their property.

Reserve Land

The Indian Act of 1873 laid out plans to create a new form of landholding in Canada; reserve lands were defined in the Act as “a tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, which has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band.” Reserve lands are not owned by First Nations; the land remains the property of the Crown, on loan, so to speak, to Indigenous Peoples. Only the First Nations can live there, and people on the reserve cannot sell, mortgage, or let non-band members use it. Any land transactions that happen on a reserve must be approved by the government.

Interactive 6.14 Whose Land website

Click the link above to visit the Whose Land website, to learn more about whose traditional lands you are on and why land acknowledgements are so important, and to watch videos of some different land acknowledgements.

References

Defalco, M., & Dunn, W. (1972). The other side of the ledger. Canada: National Film Board. Retrieved from https://www.nfb.ca/film/other_side_of_the_ledger/

Special Rapporteur. (2010). Preliminary study of the impact on Indigenous Peoples of the international legal construct known as the Doctrine of Discovery (pp. 1-22, Working paper No. 10-23102 (E) 020310). United Nations Economic and Social Council.

Media (in order of appearance)

Winterstein, S. (Photographer). (2017). Saugeen First Nation Amphitheatre & Gardens [Digital image].

Archeological Conservatory. (n.d.) Hakai ares, Calvert Island, B.C. Central Coast [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.archaeologicalconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Fall-2016-mag_Page_13_Image_0002.jpg

Bourgeon, L. (2017). Bluefish Cave Horse Mandible [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/humans-may-have-arrived-north-america-10000-years-earlier-we-thought-180961957/

Snape, C. (2014). A petroglyph believed to symbolize the circle of life [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/writing-stone-provincial-park-takes-visitors-back-time

Tourism Saskatchewan. (2018). Wanuskewin, Northern Saskatchewan [digital image]. Retrieved from https://wanuskewin.com/visit/

Brandon Sun. (n.d.) Sourisford Linear Burial Mounds [digital image]. Retrieved from http://vantagepoints.ca/stories/sourisford-linear-burial-mounds/

Washington State Archives (n.d.) Mnijikamind Fish Weirs [digital image]. Retrieved from http://muskratmagazine.com/the-secrets-of-the-mnjikaning-fish-weirs/

Drost, P. [photographer]. (2017, April 13). Image of ancient tool [photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/artifacts-new-brunswick-1.4068145

Canadian Museum of History. (n.d.) Scraper, made of chert, Eastern Clovis/Palaeo-Indian, Debert, Nova Scotia, circa 11,000 B.P. [online image]. Retrieved from https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/ethno/et0352be.shtml

Canadian Museum of History. (n.d.) Jones Site, St. Peter’s Bay, Prince Edward Island. [online image]. Retrieved from https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/lifelines/images/licro09b.jpg

Naulleau, D. (2009, July 29). Pinware Hill, Strait of Belle Isle, Newfoundland [digital image] Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinware#/media/File:Pinware,_Labrador_(NL),_Canada.JPG

Centennial College. (2018). Chief Duke Peltier discusses unceded territory [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/bEjDndEvzfk

Papal Bull Inter Caetera [digital image]. (1493). Retrieved from http://www.nmai.si.edu/exhibitions/indivisible/stolen_people.html