17 Indigenous Sports

Introduction

Indigenous involvement in sport has been and remains a vehicle through which Indigenous Peoples assert and celebrate their cultural identity. Across Turtle Island, Indigenous participation in sport is emerging as an essential lens to better understand issues around community, health, colonialism, culture, gender, and self-determination among Indigenous Peoples in Canada (Forsyth & Giles, 2013).

The Creator’s Game

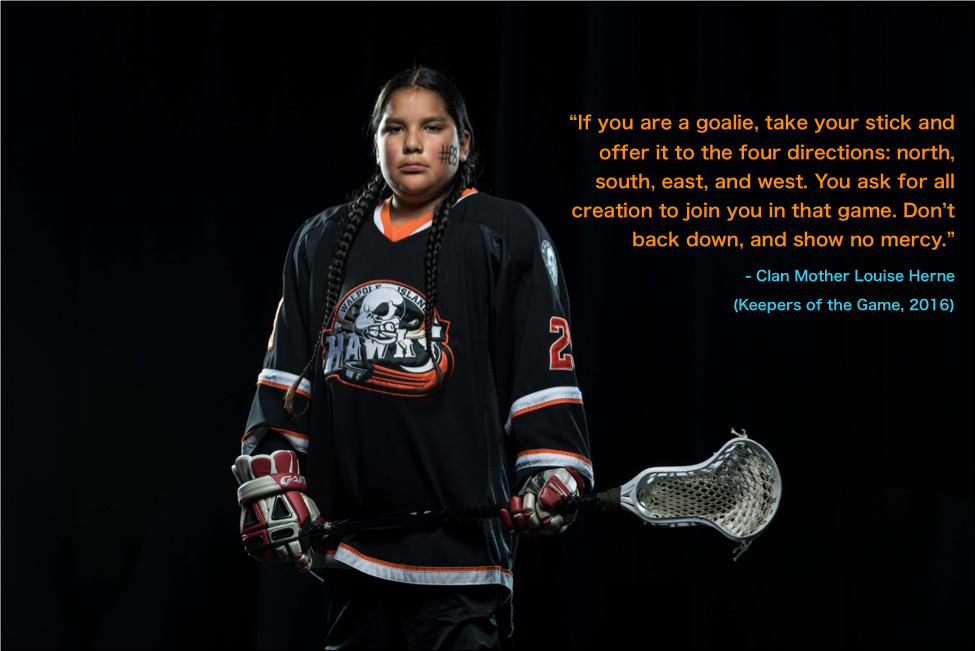

Indigenous Peoples have participated in sport since time immemorial. Early European accounts of sport on Turtle Island describe a game known today as lacrosse. Indigenous Peoples of North America referred to this game in their language as the Creator’s Game. It is one of the oldest known organized sports in North America. Before its identity as a sport, it was understood by First Peoples to be gifted by their creator for his entertainment and was traditionally played by men (Calder & Marshall, 2017; Oneida Indian Nation, 2015).

The earliest versions of the Creator’s Game involved players passing, catching, and carrying a rubber ball in a netted pouch on the end of a stick (Adamski, 2013). Oral tradition speaks of games lasting from sun-up to sundown, some stretching to more than two consecutive days. Some games were believed to have involved hundreds of warriors participating at various points over the duration of a match (Calder & Marshall, 2017).

By the mid-1700s French immigrants had renamed the Creator’s Game lacrosse and changed it to what they believed to be a “gentleman’s game,” a less violent version of the sport played on a clearly outlined field (Calder & Marshall, 2017). By the late nineteenth century, lacrosse looked reasonably different from the Creator’s Game, and Indigenous athletes were banned or excluded from playing the sport. Lacrosse in its new form was adopted by colleges and universities in the mid-twentieth century. Athletes on North American teams were predominantly white; however, Indigenous Peoples never relinquished their love and dedication to the sport (Campbell, 2017). Indigenous athletes fought to participate, and over time, adapted to and mastered the new version of the sport (Calder & Marshall, 2017).

Gallery 4.1 Ball players

The Creator’s Game has been played by Indigenous Peoples in North America since time immemorial. It is known as baggataway among the Algonquin, kabocha-toli by the Choctaw, tewaarathon by the Mohawk, and ká:lahse by the Oneida (Adamski, 2013; Calder & Marshall, 2017; Oneida Indian Nation, 2015).

The game was understood as a form of spiritual celebration and medicine for Indigenous Peoples. Warriors who participated sometimes fasted before to honour the Creator, and the game was used to solve disputes or heal members of the community (Calder & Marshall, 2017; Oneida Indian Nation, 2015; Waterman, 1999).

Traditionally the stick was made from hickory and strung with deerskin or groundhog leather. The balls were heavy and carved from wood or made of tightly bound deerskin (Calder & Marshall, 2017).

Residential Schools and Sport

When Indigenous youth were forced into residential schools, they started playing Euro-Canadian sports (Forsyth, 2007). Today many residential school survivors speak openly about the trauma of their experiences, but for some, involvement in sport offered a respite (Forsyth, 2013). Indigenous Peoples have always been, and continue to be, resilient contributors to sport.

Gallery 4.2 Residential schools and sport

Boys playing hockey at the McIntosh, Ontario, school. Many students said that they would not have survived their residential school years were it not for sports. St. Boniface Historical Society, Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Manitoba Province Fonds, SHSB 29362.

The hockey team of the residential school of Maliotenam, Quebec. [Back row, left to right: Père Laurent, Thaddeus André, Omer Rock, Jules Bacon, Donald St-Onge (Onges?), Mathias Malec (?), unidentified boy (third from right), unidentified boy (second from right), Frère Trudel. Front row, left to right: Valentin Jourdain, Louis Georges Prépeau, unidentified boy (centre), Charles St-Onge (Onges?), Sylvester Rock]

By 1951 the Department of Indian Affairs was providing funding in the form of grants to residential schools with successful physical education programs and to teams who successfully competed against other Indigenous and non-Indigenous teams in their region. However, this funding did not cover equipment or space for non-competitive activities.

Many schools lacked fitness equipment and playground infrastructure such as swings and teeter-totters, and gym classes often occurred inside modified classrooms. The absence of attention to these needs speaks to the federal focus, which was on creating a nationalistic narrative through sport and supporting players who could draw public attention, not the overall well-being of students (Forsyth, 2013).

Despite these limitations and wariness around government efforts to assimilate Indigenous youth through sport, many Indigenous communities are proud of the barriers their athletes have overcome. Today Indigenous athletes play sport at the highest level, and Indigenous communities find themselves in a position to claim proud ownership of their athletes, celebrating their triumphs and rebuilding what it means to be Indigenous in competitive sports on their own terms.

Indigenous Involvement in Canadian Sport Today

The image here is the opening face-off between the Peterborough Lakers and the Six Nations Chiefs of game 7 of the Major Series Lacrosse semi-finals at the Peterborough Memorial Centre, August 15, 2011.

To fully understand Indigenous presence in contemporary Canadian sport, it’s necessary to explore how sport is governed, supported, and managed in Canada. Sports Canada is a branch of the federal department of Culture, History, and Sport, which ensures access to sport for Canadians as part of a healthy lifestyle (Forsyth & Giles, 2013; “Sport,” 2017).

This governmental body has a partnership with the Aboriginal Sport Circle (ASC), an organization that acts as the national voice and representative body for Indigenous sport in Canada (ASC, 2017; “Sport,” 2017). The ASC was developed in 1995 in response to the demand for equitable and accessible recreation and sports opportunities for Indigenous Peoples. The ASC collaborates with popular sports organizations to overcome barriers to opportunity in sport, and ensures athletic and coaching expertise is available to Indigenous communities.

Indigenous Athletes

Today, across Turtle Island, it is evident that the federal government failed to assimilate Indigenous Peoples through sport. Instead many Indigenous Peoples recognize sport and physical activity as a form of medicine. For Indigenous communities, sports have value, and spiritual and healing potential when understood in the context of Indigenous culture and practice (Lavallee & Levesque, 2013). Under this framework Canada is experiencing a resurgence of Indigenous identity and involvement in sport.

Métis and Sport

Métis in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not have significant leisure time; they were focused on hunting and trading fur to ensure their survival. Nevertheless, communities developed many sports and games to practice and hone their hunting and trapping skills that also provided an opportunity to gather as a community and socialize (Canadian Heritage Information Network [CHIN], 2009b). These included shooting, hunting, running, canoeing, and horse-racing games (CHIN, 2009a; CHIN, 2009b). These types of sports activities allowed them to practice defending their communities while enhancing their competencies related to the fur trade (CHIN, 2009b). But competitions were not just useful, they were fun. The Métis embraced a range of sporting activities including boxing and wrestling (CHIN, 2009a, para. 1). They even transformed the Red River jig into a dance competition that coincided with a fiddling contest (CHIN, 2009a, para. 5).

Horses were particularly valued by the Métis, as they were essential for success during the bison hunt (CHIN, 2009a, para. 2). A strong bond between horse and rider could be the difference between life and death for a Métis hunter or warrior. Competitions were developed to help riders hone their skills, like picking objects off the ground on horseback at full speed and using a lasso (traditionally called “cabresser”) to throw a rope around a moving or still target (CHIN, 2009a, para. 2).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Métis life dramatically shifted with the decline of the buffalo. At the same time, Canada experienced a rapid socio-economic shift towards mechanized transportation, and urban and industrial development. The Métis, like many other Indigenous communities across Canada, turned to new sports in their communities, mainly hockey and baseball (CHIN, 2009c). The Métis of St. Boniface in Winnipeg have been credited with building some of the earliest hockey rinks in Western Canada. One of their own, Antoine Gingras, was the top scorer for the Winnipeg Victorias in the early twentieth century and later went on to become a scout for the Montreal Canadiens; he is now considered one of Canada’s greatest Métis hockey players (CHIN, 2009c, para. 4).

The Métis Nation’s celebration of sport extends well beyond hockey and baseball. Today it hosts the Métis Voyageur Games during its Annual General Assemblies. This competition is an opportunity for Métis athletes to compete at a series of athletic sporting events and skills competitions that were common during the fur trade (Métis Nation of Ontario, 2018a).

North American Indigenous Games

The North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) is a sporting event for young Indigenous athletes from across Turtle Island. The first event was staged in 1990 in Edmonton, Alberta (NAIG, 2017b). A total of nine NAIG events have been held at different locations and various intervals, with as little as two years and as many as six years between competitions (NAIG, 2017a; 2017b).

Indigenous youth between the ages of 13 and 19 participate in NAIG (NAIG, 2017a). They come from all over Canada, as well as from 13 US states (NAIG, 2017a). Fourteen competitions occur at the games. The following is a list of the competitions from the most recent NAIG event, the 2017 games in Toronto, which were held July 16-23: 3-D archery, athletics, badminton, baseball, basketball, canoe/kayak, golf, lacrosse, rifle shooting, soccer, softball, swimming, wrestling, and volleyball (NAIG, 2017a).

Today NAIG is the most significant sporting and cultural event for Indigenous Peoples in North America (NAIG, 2017a).

Gallery 4.3 NAIG 88 Days Out celebration in Toronto

Call to Action #88: We call upon all levels of government to take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel.

North American Indigenous Games Mascot

For the 2017 games, NAIG held a mascot contest for youth in Ontario (NAIG, 2017c). From over 100 entries from Indigenous youth across Ontario, an image of a turtle named Debwe was selected as the official mascot design for the 2017 games (NAIG, 2017c).

The name Debwe (pronounced phonetically DAY-BH-WAY) is from the Anishinaabe language and means “the one who speaks the truth” (NAIG, 2017c, para. 2). Debwe was the artistic creation of Anton, a 14-year-old from Deer Lake First Nation in north-western Ontario. Deer Lake is a small, fly-in community, with a little over 1000 residents. Anton wanted to create a mascot that would represent the hope and opportunity that sports bring to Indigenous youth all over North America (NAIG, 2017c), and he drafted the mascot with the seven grandfather teachings in mind (NAIG, 2017c, para. 4). Anton’s design was chosen by the Host Society in Toronto for representing and celebrating the valuable life lessons that are experienced through participating in sport and engaging with Indigenous cultural traditions (NAIG, 2017c). The turtle is at the heart of creation stories for many Indigenous Nations in Central and Eastern Canada.

References

Aboriginal Sport and Recreation Circle. (2008, October). Tom Longboat Award. Retrieved from: http://www.asrcnl.ca/home/7

Aboriginal Sport Circle. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.aboriginalsportcircle.ca/en/about-us/history.html

Adamski, B. K. (2013). Lacrosse. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lacrosse/

Black, M. J. (2007). Algonquin. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/algonquin/

Calder, J., & Marshall, T. (2017). Lacrosse: From Creator’s Game to modern sport. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lacrosse-from-creators-game-to-modern-sport/

Campbell, M. (2017, July 22). How Indigenous people in Canada are reclaiming lacrosse. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/society/how-indigenous-canadians-are-reclaiming-lacrosse/

Canadian Heritage Information Network. (2009a). Métis games for entertainment. Retrieved from http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do?method=preview&lang=EN&id=11582

Canadian Heritage Information Network. (2009b). Métis games of character. Retrieved from http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do?method=preview&lang=EN&id=11562

Canadian Heritage Information Network. (2009c). Métis games, the evolution of hockey. Retrieved from http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do?method=preview&lang=EN&id=11597

Casole-Gouveia, T. (2016). NHL’s Carey Price is just one of Canada’s notable Aboriginal athletes. CBC Sports. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/sports/national-aboriginal-day-athletes-sports-1.3645546

Commito, M. (2016, June 15). Reggie Leach. In Historica Canada. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/reggie-leach/

Coubrough, J. (2015, April 24). Canada’s 1st indigenous Olympic gold medallist not recognized, family says. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/canada-s-1st-indigenous-olympic-gold-medallist-not-recognized-family-says-1.3046786

Delsahut, F., & Terret, T. (2014). First Nations women, games, and sport in pre- and post-colonial North America. Women’s History Review, 23(6), 976-995. doi:10.1080/09612025.2014.945801

Ehrlich, J. (Director). (2016). Keepers of the game [Documentary]. Retrieved from https://www.netflix.com/ca/title/80105881

Forsyth, J. (2007). The Indian Act and the (re)shaping of Canadian Aboriginal sport practices. International Journal of Canadian Studies, (35), 95-111. doi:10.7202/040765a

Forsyth, J. (2013). Bodies of meaning: Sports and games at Canadian residential schools. In J. Forsyth, & A.R. Giles (Eds.), Aboriginal Peoples & sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 15-34). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Forsyth, J., & Giles, A. (Eds.). (2013). Aboriginal Peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 1-254). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Hockey Hall of Fame. (2018). Legends of hockey: George Armstrong. Retrieved from http://www.legendsofhockey.net/LegendsOfHockey/jsp/LegendsMember.jsp?mem=p197501&page=bio

Hockey Hall of Fame. (2018). Legends of hockey: Reggie Joseph Leach. Retrieved from http://www.hhof.com/LegendsOfHockey/jsp/SearchPlayer.jsp?player=10916

Laskaris, S. (2014, November 1). 9 Native NHL players to watch this season. Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved from https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/sports/9-native-nhl-players-to-watch-this-season/

Lavallee, L., & Levesque, L. (2013). Two eyed seeing: Physical activity, sport, and recreation promotion in Indigenous communities. In J. Forsyth, & A.R. Giles (Eds.), Aboriginal Peoples & sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 206-228). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

McCue, D. (2014, March 26). How hockey offered salvation at Indian residential schools. CBC News: Indigenous. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/how-hockey-offered-salvation-at-indian-residential-schools-1.2583531

Métis Nation of Ontario. (2018a). Métis Voyageur Games to be featured on APTN program. Retrieved from http://www.metisnation.org/news-media/news/m%C3%A9tis-voyageur-games-to-be-featured-on-aptn-program/

Métis Nation of Ontario. (2018b). Who are the Métis. Retrieved from http://www.metisnation.org/culture-heritage/who-are-the-m%c3%a9tis/

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne. (2018). The Creator’s Game: A history of lacrosse. Retrieved from http://www.akwesasne.ca/node/275

North American Indigenous Games. (2017a). About. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/about/

North American Indigenous Games. (2017b). FAQ. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/about/faqs/

North American Indigenous Games. (2017c). Toronto 2017 NAIG mascot. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/about/toronto-2017-naig-mascot/

Oneida Indian Nation. (2015). Ká:lahsé: A Haudenosaunee tradition. Shako:wi Cultural Center. Retrieved from https://www.oneidanationlacrosse.com

Paraschak, V. (2008). Reasonable amusements: Connecting the strands of physical culture in Native lives. Sport History Review, 28(1), 121-131.

Paraschak, V. (2013). Aboriginal Peoples and the construction of Canadian sport policy. In J. Forsyth & A. R. Giles, (Eds.), Aboriginal Peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. pp. 95-123.

Rosenbaum, C. (2016). ‘Keepers of the game’ showcases evolving Mohawk lacrosse culture. Indian Country Today. Retrieved from https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/arts-entertainment/keepers-of-the-game-showcases-evolving-mohawk-lacrosse-culture/

Sport. (2017). Department of Culture, History, and Sport. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/services/culture/sport.html

Underwood, K. (2015, December 23). Ms. Chatelaine: Champion boxer Mary Spencer. Chatelaine. Retrieved from http://www.chatelaine.com/living/ms-chatelaine/boxer-mary-spencer/

Waterman, D., & Waterman, P. (1999). The story of lacrosse. Iroquois Nationals. Retrieved from http://iroquoisnationals.org/the-iroquois/the-story-of-lacrosse/

Media (in order of appearance)

North American Indigenous Games 2017 (2017). Team #88 Players [digital image]. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/team-88/about-88/

Caitlin, G. [artist]. (n.d.). Ball-play Dance [painting]. Renwick Gallery, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ball_play_dance.jpg

Caitlin, G. [artist]. (n.d.). Ball Players [lithograph]. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ball_players.jpg

Miniature Lacross Stick [lacrosse stick]. (c. 19th C). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/319049

Caitlin, G. [artist]. (1846-50). Ball-play of the Choctaw–Ball Up [painting]. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/ball-play-choctaw-ball-3886

McIntosh, Ontario [photograph]. (n.d.). Fond 0096, Ref. SHSB 29362. Centre du patrimoine, La Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Saint-Boniface, MB. Retrieved from http://archivesshsb.mb.ca/en/permalink/archives79786

The hockey team of the residential school of Maliotenam, Quebec [photograph]. (c. 1950). MIKAN 3601416 . Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2018-06-12T16%3A11%3A11Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=3601416&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng

Group of students playing field hockey or lacrosse on a field, Cariboo Indian Residential School, William’s Lake, British Columbia, 1949 [photograph]. (1949). MIKAN 4674076. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2018-06-07T19%3A22%3A53Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=4674076&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng

Norway House. Residential school, interior. Girls’ gym class 1962 [photograph] (1962). United Church Archives, Winnipeg, MB. Retrieved from http://uccarchiveswinnipeg.ca/tag/campbell-fonds-photos/?mctmCatId=162&mctmTag=campbell-fonds-photos

Copperknob39 [photographer]. (2011, August 15). Native American Lacrosse Stick (field) [digital image]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lakers_vs_Six_Nations_(Game_7_MSL_Semi-Finals,_15-AUG-2011).jpg

North American Indigenous Games 2017 (2017). [North American Indigenous Games 2017 logo]. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/

North American Indigenous Games 2017 (2017). Team 88 [digital image]. Retrieved from http://naig2017.to/en/media/gallery/