22 Indigenous French-English Relations

Prior to the Nation State of Canada

Many of the discussions we have in Canada about the relationship between the nation state and Indigenous Nations make two assumptions: First, we forget that before 1867, the Government of Canada did not exist; power rested with the (unelected) monarchies (kings and queens) of England and France. These ruling powers in Europe negotiated a number of deals (treaties) with Indigenous groups, so when Canada became a new independent nation, these pre-existing treaties had to be dealt with. In some cases (such as in the Royal Proclamation) they were absorbed into the British North America Act (1867). In other cases, there remain disagreements between First Nations and Canada about how these agreements have been incorporated into Canada’s legal frameworks.

The second assumption we often make, especially in English-speaking Canada, is that events of the recent and historical past happened in English. As the dominant of the two official languages in most of Canada, English is often taken for granted. The historical relationship between French and English Canada, the presence of Indigenous francophone communities, and the experiences of Indigenous Peoples living in francophone-dominant cultures are often forgotten in our stories and classroom discussions. In a similar vein, we often neglect to consider the role that language differences, language barriers, and other communication challenges played for First Nations who were trying to negotiate fair and sustainable deals that would ensure their peoples’ survival and well-being.

History of French Relations with Indigenous Peoples

Historically, the French have had both positive and negative relationships with different Indigenous groups. Positive relationships were sometimes forged in business, particularly during the fur trade. There was also a long history of negative relationships; for example, the famous explorer Jacques Cartier kidnapped two men and brought them to France as proof of the so-called New World. These young men were sons of Chief Donnacona, whose settlement called Stadacona was located where Quebec City is today. It is from these men that Cartier learned about Hochelaga (Montreal), which he would explore on subsequent trips to the region.

The Acadians

Beginning in the early 1600s, French farmers began to arrive in what is now Eastern Canada, and over time, they developed their own culture and traditions, with influences from French, Catholic, and Mi’kmaq cultures. These people and their culture came to be known as “Acadian.” It was a difficult time to be living in this region of Turtle Island, which was beset with conflicts as the French and English fought over control of the land, and official rule passed from one to the other many times. Finally in 1713 the British gained control of the area; once established, they sought to make allies with the Acadians, but the Acadians refused. Instead, they signed a neutrality agreement, stating they would be neutral so long as they did not have to fight against the Mi’kmaq or the French.

To learn more about this period of history, read about the Seven Years War in which New France was lost to the British.

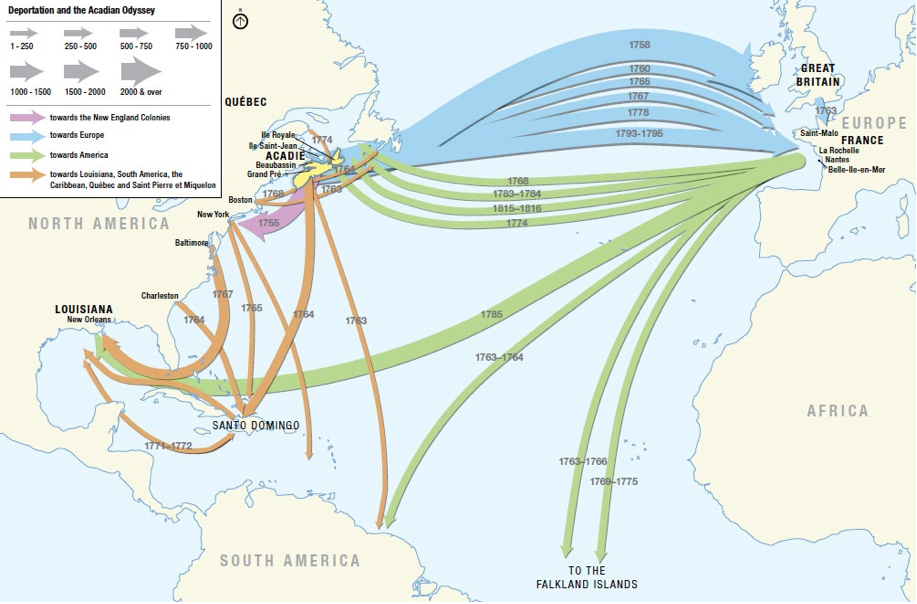

For the Acadians, who were French-speaking, Catholic, and closely tied to the Mi’kmaq, living under British control was difficult, and the British came to see the Acadians as a threat to their settlement and control of the rich farmlands. In the mid-1700s the British began forcibly removing Acadians from the land, and about 10,000 Acadians were sent away. Some ended up forming communities in Louisiana and other parts of the US (today these people are known as the Cajuns), some were deported back to France, and others went as far as Guyana and present-day Haiti to build new lives.

References

Cartier, J., Biggar, H. P., & Cook, R. (1993). The voyages of Jacques Cartier. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Faragher, J. M. (2006). A great and noble scheme: The tragic story of the expulsion of the French Acadians from their American homeland. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

Gross, K. (1990). Coureurs-de-bois, voyageurs and trappers: The fur trade and the emergence of an ignored Canadian literary tradition. Canadian Literature, 127, 76-91.

Hodson, C. (2012). The Acadian diaspora: An eighteenth-century history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maison Saint-Gabriel Museum and Historic Site. (n.d.). Chronicles – Running through the woods: The coureurs des bois. Retrieved from http://www.maisonsaint-gabriel.qc.ca/en/musee/chr-08.php

Marsh, J. (2013). The deportation of the Acadians. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-deportation-of-the-acadians-feature/

Podruchny, C. (2006). Making the voyageur world: Travelers and traders in the North American fur trade. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Seixa, P., & Morton, T. (2013). The big six historical thinking concepts. Toronto, ON: Nelson Education Ltd.

Was the Acadian expulsion justified? [Blog post] (2017, February 25). All about Canadian History. Retrieved from https://cdnhistorybits.wordpress.com/2016/12/13/was-the-acadian-expulsion-justified/

Media (in order of appearance)

Remington, F. (1891). The Courier du Bois and the Savage [painting]. Sid Richardson Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. Retrieved from https://www.sidrichardsonmuseum.org/gallery.php/art/courrier-du-bois

Destinations and movements of the deportees during the Acadian Odyssey [Digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.landscapeofgrandpre.ca/deportation-and-new-settlement-1755ndash1810.html