8 Human Rights

United Nations Declaration on the Rights for Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an international declaration adopted by the United Nations to enshrine the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of the world” (UNDRIP, n.d.). UNDRIP seeks to protect “collective rights that may not be addressed in other human rights charters that emphasize individual rights, and it also safeguards the individual rights of Indigenous people” (UNDRIP, n.d.).

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an international declaration adopted by the United Nations to enshrine the rights that “constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of the world” (UNDRIP, n.d.). UNDRIP seeks to protect “collective rights that may not be addressed in other human rights charters that emphasize individual rights, and it also safeguards the individual rights of Indigenous people” (UNDRIP, n.d.).

This declaration took over 20 years of negotiation to achieve. UN member states, UN agencies, and Indigenous Peoples from across the globe participated in creating the document. It is the only human rights declaration in the world created with the participation of the rights holders themselves, and it specifically recognizes that Indigenous Peoples’ rights are both individual and collective.

On September 13, 2007, the day of the UN General Assembly vote to adopt the declaration, the majority of member states (144) voted in favour. Four member states voted against: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. Canada changed its position on UNDRIP in 2016.

UNDRIP Strengths

A minimum international standard: This declaration articulates the floor (the minimum), not the ceiling (the maximum), of rights that governments everywhere are expected to grant and support for Indigenous Peoples.

An expectation of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC): The declaration states that Indigenous Peoples must have free, prior, and informed consent with regard to decision-making that impacts their lives and communities. The practical application of this concept is challenging to settler institutions and governments. Nonetheless, this idea could be the most powerful aspect of UNDRIP in the long term.

Interactive 1.24 UNDRIP

http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Click the above link to open and read the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

UNDRIP Weaknesses

Not binding: Unlike a treaty or a contract, a declaration of this nature is non-binding for member states. A declaration “represents the dynamic development of international legal norms and reflects the commitment of states to move in certain directions, abiding by certain principles” (United Nations, 2007). This means there are no legal consequences or enforcement policies that come into effect if a member state does not meet the minimum human rights standards set out in UNDRIP.

Too broad and open to interpretation: In December 2017, the Canadian House of Commons debated a private member’s bill (Bill C-262) that would require the federal government to “take all measures necessary to ensure that the laws of Canada are consistent” with UNDRIP. Bill C-262 also requires the federal government to develop a national action plan to implement UNDRIP in “consultation and cooperation” with Indigenous Peoples. As of this writing, the bill has passed the second reading in the House of Commons.

The interpretation and understanding of UNDRIP remains strongly contested.

The federal Liberals have contradicted themselves on multiple occasions about what UNDRIP means while some Indigenous scholars have an altogether different take on what the declaration truly means for Indigenous sovereignty and nationhood. (Wilt, 2017)

In article in DeSmog Canada, Russ Diabo, “a Kahnawake Mohawk policy advisor,” was quoted as saying, “When they say they’re going to support Bill C-262, I just view it as a PR stunt” (Diabo, cited in Wilt, 2017). According to the article, “the federal government isn’t prepared to fully face the implications of UNDRIP, Diabo said, and how it could challenge Canada’s current legal frameworks” (Wilt, 2017).

Not meaningfully enforceable

Article 46: Article 46 is the last section of UNDRIP. It states that “nothing in UNDRIP may be interpreted as authorizing or encouraging any ‘action which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent States’” (Wilt, 2017). Canada is, of course, a sovereign and independent state. Many elements of UNDRIP could be viewed as threatening Canada’s status as a nation, meaning Article 46 significantly weakens the degree to which UNDRIP can be implemented (Wilt, 2017).

Altered wording: Dr. Sheryl Lightfoot, author of Global Indigenous Politics: A Subtle Revolution, notes that some last-minute wording changes to UNDRIP significantly impacted its meaning and interpretation. The final draft of the declaration was written by states alone without input from Indigenous communities (“A Subtle Revolution,” 2017).

In the last few months, Indigenous Peoples were no longer in the room and no longer a part of the process. As a result, the final text includes some highly objectionable provisions. These are provisions that Indigenous Peoples never agreed to, particularly Article 46 which provides extra protections, as if they needed more, for states sovereignty and territorial integrity. It removes completely Indigenous Peoples’ right to form their own states. (Dr. Sheryl Lightfoot in “A Subtle Revolution,” 2017)

Government of Canada’s Response to UNDRIP

September 2007: UNDRIP was formally adopted by the United Nations. Canada was one of four countries to cast an opposing vote.

2010: The Canadian government under Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper “endorsed” UNDRIP but called it an “aspirational document” (“Canada endorses Indigenous rights legislation,” 2010). The Canadian government did not remove its permanent objector status.

October 2015: One of the Liberal Party’s promises during the federal election campaign was that it would “enact the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, starting with the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” (Liberal Party of Canada, n.d.). The Liberal Party won in a landslide vote and Justin Trudeau became prime minister.

May 2016: Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations for the Canadian government, officially removed Canada’s permanent objector status to UNDRIP, paving the way for implementation in Canada.

July 2016: Jody Wilson-Raybould, Minister of Justice, made the following statement to the 37th General Assembly of First Nations:

Simplistic approaches such as adopting the United Nations declaration as being Canadian law are unworkable and, respectfully, a political distraction to undertaking the hard work actually required to implement it back home in communities. (APTN National News, 2016)

Wilson-Raybould is herself a former regional chief of the BC Assembly of First Nations and a descendant of the Musgamagw Tsawataineuk and Laich-Kwil-Tach Peoples, who are part of the Kwakwaka’wakw and also known as the Kwak’wala speaking peoples (PMO, 2015).

September 2017: September 13, 2017, marked the tenth anniversary of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Canada has finally endorsed UNDRIP and the Trudeau government has committed to implementing it. However, many questions remain: “What does implementation mean and what is required of federal, provincial and local government, political and social institutions, and civil society to make the UN Declaration a reality in Canada?” (“A Subtle Revolution,” 2017).

Interactive 1.25 CBC The National: Canada removes objector status to UNDRIP

In the spring of 2016, Canada removed its “permanent objector status” to the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

A Selection of Voices 10 Years After UNDRIP

Littlechild and Palmater

Chief Wilton Littlechild, one of the authors of UNDRIP and a commissioner for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, approves of Canada’s progress so far.

As I have travelled across the country to many places, I have witnessed and am very encouraged by governments at all levels, private industry, educational institutions, sports events, the medical and legal communities, faith groups and importantly Indigenous Peoples’ communities all engaged at different levels, in different ways on implementation. We still, of course, have a long way to go, but I think we are on a good path of reconciliation. (Littlechild as quoted in Morin, 2017b)

Mi’kmaq lawyer, professor, and activist Pam Palmater, on the other hand, does not believe that Canada is actually doing what is necessary to implement the declaration. As cited in Morin (2017b), “She said the government spends more time boasting about getting the work done than actually doing anything.” Furthermore, she believes:

Canada is fooling people when it says it unconditionally supports UNDRIP. All they have done is talk about it and set up processes to engage in more talk about it, but they have not started the legal process of implementation. The biggest challenge is always political will. Governments can literally talk about good ideas, plans and commitments for years and never take any real concrete action. This Liberal government has, for the most part, been more talk and less action. They are skilled in delaying action under the guise of consultation. (Palmater as quoted in Morin, 2017b).

Interactive 1.26 APTN News: Roy-Henriksen discusses UNDRIP a decade after its adoption

Nearly a decade after the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, many of those rights remain unrealized, according to a statement of the UN permanent forum on Indigenous issues.APTN National News speaks with Chandra Roy-Henriksen, who is with the forum.

Lightfoot and Phillip

In September 2017, Dr. Sheryl Lightfoot, author of Global Indigenous Politics: A Subtle Revolution, spoke at a Simon Fraser event called A Subtle Revolution: What Lies Ahead for Indigenous Rights? which marked the tenth anniversary of the passing of the UN Declaration in 2007. Lightfoot is Anishinaabe, a citizen of the Lake Superior band of Ojibwe, enrolled at the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community in Baraga, Michigan, and an associate professor in First Nations and Indigenous Studies and the Department of Political Science at UBC. She made the following remarks:

The Indigenous world remains under what we could call severe stress. From Brazil to Botswana, from Australia to Ecuador, from Myanmar to Standing Rock, Indigenous Peoples are on the front lines, fighting for their cultural survival, their languages, their ways of life, their political and legal institutions, their territories including both lands and waters, and their lives. In fact, the UN reports that 2016 had the highest number of deaths of human rights defenders than any other year in recorded history. (“A Subtle Revolution,” 2017).

Speaking at that same event, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, made the following remarks:

We had pretty much a decade being in the trenches fighting the Harper government. It may shock you that sometimes I would much prefer to fight with an individual like Mr. Harper who is absolutely racist. (He) was a terrible prime minister, and now we have Mr. Selfie, Justin Trudeau, the charmer, who believes that somehow he can achieve reconciliation between the Federal Crown and Indigenous Peoples through selfies. The eloquent statements that he makes publicly about the need to move forward on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the 94 Calls to Action with the TRC. I remember October the 20th, the day after the election, when we couldn’t believe that Mr. Harper was gone. There was a sense of hope, that there would be space and opportunity to move our issues forward. We were engaged in a very vigorous campaign against the Site C Dam, against Lelu Island, the massive LNG facility that was being promoted by the former BC Liberal government in Petronas, (against) the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline. We were hugely disappointed after the election when Mr. Trudeau and his government approved the permits for Site C, approved Lelu Island, I believe they did it late Friday, very sneaky, before a long weekend, and of course greenlighting the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline knowing full well that there was enormous Indigenous opposition to those projects. The violation of Treaty 8’s rights flies in the face of Mr. Trudeau’s eloquent, warm, fuzzy statements about “nothing is more important to this government than a nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples of this country.” (“A Subtle Revolution,” 2017)

Snapshots: The Reality of Indigenous Rights in Canada Since 2007

Given the passage of UNDRIP and Canada’s stated commitment to abide by the provisions within it, it would be reasonable to expect that the quality-of-life issues such as housing, water, education, and health care would have become areas of focus for improvement. The following examples illustrate the reality of these issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada as of February 2018. These examples are intended to be representative of life as lived by Indigenous communities in Canada rather than a comprehensive or exhaustive study of these issues.

Water

In June 2016 a report was issued by Human Rights Watch (HRW), an international rights group, that accused the Canadian government of violating its human rights obligations towards Indigenous Peoples by failing to adequately address the water crisis on reserves. From July 2015 to April 2016 researchers with the international rights group investigated how the lack of clean running water affects hundreds of people living on five First Nations reserves:Batchewana, Grassy Narrows, Shoal Lake #40, Neskantaga, and Six Nations of the Grand River. HRW’s additional water and sanitation survey, covering 99 households with 352 people, found rampant health problems among those living without sanitary water for drinking and bathing. “Many households surveyed by Human Rights Watch reported problems related to skin infections, eczema, psoriasis, or other skin problems, which they believed were associated with water conditions in their homes,” states the 92-page report entitled Make It Safe: Canada’s Obligation to End the First Nations Water Crisis (Browne, 2016).

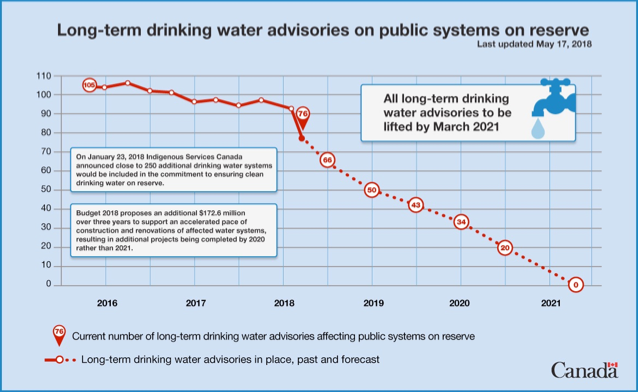

The Government of Canada has made a public commitment to end all water advisories on First Nations reserves by 2021. However, the accuracy of the Government of Canada’s reporting has been called into question.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC, now split into two distinct ministries) claimed progress had been made and produced “a list of 15 water advisories on 11 reserves it says have been resolved. Of the 11 reserves on the agency’s list, six are still considered by Health Canada to have undrinkable water” (Beaumont, 2016).

Interactive 1.27 Human Rights Watch: Canada’s water crisis: Indigenous families at risk

Canada has abundant water, yet water in many Indigenous communities in Ontario is not safe to drink, according to Human Rights Watch. The water on which many of Canada’s First Nations communities on lands known as reserves depend, is contaminated, hard to access, or at risk due to faulty treatment systems. The federal and provincial governments need to take urgent steps to address their role in this crisis.

What follows are some examples of the issues faced by Indigenous communities in securing fresh drinking water.

Water: Potlotek

Potlotek is a small First Nation in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Headlines abounded in September 2016 when members of the community reported filthy black water flowing from their taps. Although Potlotek has a water treatment plant, they don’t use the water from it. Band manager Lindsay Marshall said, “It’s only good for firefighting and toilets. Dogs won’t even drink it” (Marshall as quoted in Beaumont, 2016).

According to Indigenous Affairs, design work for a new water treatment plant that would filter out iron and manganese is supposed to begin soon. However, the new plant is slated to be built next to the old one and will draw water from the same lake. That lake is only 55 feet from the reserve’s sewage lagoon, and the lagoon spills over into the lake during storms (Beaumont, 2016). “Marshall said the band is drilling wells to find a new source of water, and Indigenous Affairs is providing bottled water as an interim solution” (Beaumont, 2016).

Water: Nazko

On November 20, 2015, INAC stated that a 16-year boil water advisory in Nazko, a reserve in northern British Columbia, had ended. After testing the reserve’s water herself, Lena Hjorth does not believe the government’s claim: “I don’t trust it either myself,” she said. “I don’t drink it. Because there’s still arsenic in there” (Hjorth as quoted in Beaumont, 2016). This community’s situation is frustrating given that there is a new treatment plant in the middle of the reserve. Nazko’s water treatment plant became operational in 2013, at a cost of $3.6 million. It has experienced one breakdown after another, including:

- An airlock in the chlorine injection line

- A problem with the manganese and arsenic filters that caused them to stop working

- A faulty backflow check valve that needed replacing

- A breakdown of the backup generator (McCue, 2015)

Jerry Laurent, the plant operator, described the situation: “I phone people to come out and fix it. But they phone up the band office. They have to OK it first. They say there’s no funding in place for it. So, the band office has to phone down to Vancouver to AANDC…” (Laurent as quoted in McCue, 2015). Nazko Chief Stuart Alec described how demoralizing the situation has become: “It’s very upsetting. We live in Canada but on reserve it feels like Third World conditions. Drinking, bathing – it’s pretty appalling these conditions exist in this country” (Alec as quoted in McCue, 2015).

Interactive 1.28 CBC The National: Water advisories chronic reality in many First Nations communities

Two-thirds of all First Nation communities in Canada have been under at least one drinking water advisory at some time in the last decade.

Water: Shoal Lake #40

Shoal Lake #40, an Ontario Ojibwe reserve, has had to boil its water for the last 20 years. Ironically, Shoal Lake #40 is surrounded by water and on an original canoe trade route that has existed for centuries. However, in 1915, the City of Winnipeg was allowed to relocate the community to allow the City to draw its water from a clean and accessible source. To facilitate this, the Government of Canada expropriated over 33,000 acres of land from the Shoal Lake #40 community, without consent or negotiation. The people of Shoal Lake #40 were deposited on a man-made island  that has no road access and, as of about 20 years ago, no access to its own clean water. The canal that surrounds the island was constructed to divert dirty, unusable water away from the clean water source used by the City of Winnipeg, 200 kilometres to the west. The lack of road access means all supplies, including potable water, must be delivered by barge. This has made it impossible for the Shoal Lake #40 community to construct a water treatment facility as the materials for such construction cannot be effectively delivered by barge.

that has no road access and, as of about 20 years ago, no access to its own clean water. The canal that surrounds the island was constructed to divert dirty, unusable water away from the clean water source used by the City of Winnipeg, 200 kilometres to the west. The lack of road access means all supplies, including potable water, must be delivered by barge. This has made it impossible for the Shoal Lake #40 community to construct a water treatment facility as the materials for such construction cannot be effectively delivered by barge.

There are additional impacts to the lack of road access. These include:

- Substandard housing, as construction materials are difficult to transport

- Waste management issues, as garbage needs to be shipped off the island by barge and it often piles up on the limited amount of land granted to the Shoal Lake #40 band

- Sewage leakage into the existing water supply due to insufficient sewage treatment.

Gallery 1.12 Shoal Lake #40

After much lobbying and negotiation, funding has been provided by the Government of Canada, the Province of Manitoba, and the City of Winnipeg to construct a 24-kilometre access road to connect the Shoal Lake #40 to the local road system. Construction began in June 2017 and the road should be complete by fall 2018. The road, dubbed Freedom Road, will mean that supplies, including drinking water, can be transported at less cost and with greater reliability.

Interactive 1.29 Vice News: Canada’s waterless communities: Shoal Lake 40

https://youtube.com/watch?v=KHOJ0c2izbo

VICE goes to Shoal Lake 40, a reserve only a few hours from Winnipeg that sits on a manmade island. The lake the reserve sits on supplies Winnipeg’s drinking water, but Shoal Lake 40 has been under a boil water advisory for 17 years.

Water: Pikangikum Working Group

The Pikangikum Working Group (PWG) is a collection of Ontario professionals who donate their time and money to assist Pikangikum, one of the province’s most impoverished First Nations. Pikangikum is located in northwest Ontario, about a 22-hour drive from Toronto. It is a settlement of about 2800 people who live in 450 homes. Until recently, most homes had no running water or indoor toilets. The PWG consults closely with the community and designs its assistance based on identified needs and achievable outcomes (Hough, 2015).

One of the first projects addressed was the provision of running water to as many homes as possible, beginning with the homes most in need (Steeves, 2017). The cost for the first 10 homes was approximately $250,000 with the bulk of the money originating from the Anglican Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund. Additional funds were raised through St. Paul’s Anglican Church and Timothy Eaton United Church in Toronto. Private donations provided the balance. The federal government provided approximately $40,000 to train Pikangikum workers in electrical and plumbing trades to assist with installation and ongoing maintenance of the systems (Hough, 2015).

Housing

In March 2017 Kevin Hart, a regional chief with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) in Manitoba, estimated that approximately 175,000 houses are needed for Indigenous Peoples across Canada. The Government of Canada estimated the need to be around 21,000. Hart noted that this discrepancy meant that “we’re being set up for failure right off the bat” (Hart as quoted in APTN National News, 2017).

In 2007 the Harper government established a First Nations housing program with the objective of building 25,000 new Indigenous-owned homes within 10 years. Nine years later, after the government transitioned to the Trudeau administration, fewer than 200 had been built (“Editorial: Indigenous housing crisis takes a terrible toll,” 2016). More than $8 billion was allotted in Trudeau’s 2016 budget for Indigenous Peoples; just over $500 million of that was to be spent on housing across the country. The money was to be spread out over two years. Each year, the federal government expected to build 300 homes with that investment as well as provide 340 lots with sewer hookups and renovate an additional 1400 homes (APTN National News, 2017).

Based on the government’s estimate of 21,000 new homes required for Indigenous communities, building 600 new homes within a two-year period would address about three percent of the identified need. The funding barely makes a dent in the housing crisis if one considers the AFN estimate that 175,000 homes are needed (APTN National News, 2017).

In February 2018 a new federal budget was announced and it included nearly $5 billion in new funding for drinking water, housing, and health (APTN National News, 2018).

Charlie Angus, Member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay, has requested statistics on the number of houses built on every reserve in 2016-2017. The government has not provided them. An access to information request in 2016 came back almost completely blacked out. Angus wonders at this lack of transparency: “Canadians have to ask themselves what exactly the Department of Indian Affairs is doing when a simple request about the state of housing and housing plans is considered a state secret” (Angus as quoted in APTN National News, 2017).

What follows are some examples of the housing issues facing Indigenous communities.

Interactive 1.30 APTN News: Housing crisis deconstructed

Reporter Melissa Ridgen looks into the billions of dollars in federal funds spent fighting the ballooning housing crisis on Canada’s First Nations.

Housing: Garden Hill

In Garden Hill First Nation in Manitoba, 3500 residents share 500 homes. In some cases, three or four families share a single residence. Sharon Beardy shares a three-bedroom home with 12 people: “My grandkids all sleep on the floor here as you can see. One mother with two little ones and my four grandkids just sleep anywhere. Anywhere possible on the floor” (Beardy as quoted in APTN National News, 2017). A typical home has been repaired multiple times with foam insulation spray and has an external layer of plastic sheeting to help keep wind and moisture out of the inadequately sided structure (APTN InFocus, 2017). Another two-bedroom home in Garden Hill houses 15 people in total. Unlike the Beardy home, this home does not have running water (APTN InFocus, 2017).

Housing: Kitcisakik and Attawapiskat

Kitcisakik, an Anicinape First Nation that is a five-hour drive north of Montreal, is known for its extremely poor living conditions. Four hundred people live without electricity, running water, or a sewage system. Community spokesperson Charlie Papatie describes the situation: “A shower and toilet is what’s missing. That’s what the people in our community are always talking about it. They tell me they would like all those basic needs for their children” (Papatie as quoted in APTN National News, 2017).

Attawapiskat, Ontario, is one of most widely discussed reserves in need of housing solutions. This community has about 340 homes for 2100 residents, with an average of seven people living in each home. Some house as many as 13 people. Attawapiskat sits on muskeg – soft, marshy wetland – in a region where temperatures can plunge into the minus-50s. Thus, home construction poses special challenges. About 75 percent of the houses were built between 1960 and the 1990s, and were poorly designed for the freezing/thawing land below them. The spring thaw always brings shifting structures, cracked walls, flooding, leaks, and mould (Perkel, 2016).

Teresa Kataquapit’s three-bedroom home has broken, loose, and stained ceiling tiles, heaving and cracked linoleum floors, and plastic-covered, boarded-up windows. “It’s very cold […] You can feel the drafts all over the place, the windows, the doors, everywhere. There’s mould in this house” (Kataquapit as quoted in Perkel, 2016). As is the case for almost 25 percent of the homes on this reserve, it has been condemned as unfit for human habitation. Kataquapit continues to reside in this structure along with five others. It is heated by a single wood stove. She has nowhere else to live (Perkel, 2016).

Education

It does not take much imagination to conclude that communities struggling with housing and water issues are also in dire need of support with regard to education. The same construction challenges that plague water treatment, sewage treatment, and housing also apply to the construction of safe and suitable school buildings. Qualified teachers and other resources are difficult to secure and retain in many remote communities. Many such communities are so small, and have such extreme distances between them, that a school board or system, as envisioned by European settler communities, faces little chance of succeeding.

Interactive 1.31 16×9: Failing Canada’s First Nations children

Canadian kids from isolated communities are forced to move away from their families – just to go to school.

Travelling for Post-Secondary

This is the choice faced by the majority of Indigenous youth in remote reservations in Canada. Indigenous teens know a high school diploma is essential to reaching their long-term goals; however, there are almost no opportunities to advance beyond Grade 8 in most remote locations. Their departure from their home communities and traditions at a formative stage in life is painful and extremely difficult. There are risks inherent in living alone in a settler urban culture, without the support of family groups.

For northern Ontario communities, Thunder Bay is often the destination for young Indigenous people looking to complete their education. Between 2000 and 2011 seven Indigenous youth who had travelled to Thunder Bay for high school died. When interviewed by the CBC on this subject, Indigenous author Tanya Talaga said:

All the students, all seven of them, had left their northern homes, 500 to 600 kilometres away, to come by themselves to Thunder Bay to go to school. Five of them died in the waters surrounding Thunder Bay. Two died in their boarding homes.

They all didn’t have a proper high school for them to go to and I just couldn’t believe that in this day and age, we were still sending kids out of their communities, away from their languages and away from their parents to go live by themselves in boarding houses with people who are paid to look after them. It was just, it was stunning to me. How come in a country like Canada we don’t have schools, high schools for kids to go to? (Talaga, 2017).

Interactive 1.32 CBC The National: First Nations families weigh children’s education vs. safety

CBC The National meets with two First Nations’ families having to decide about sending their children away for secondary school education.

Completion Rates

In 2011 post-secondary completion rates for First Nations youth were 35.2 percent compared to 78 percent for non-Indigenous youth (Morin, 2017a). Andrew Parkin, author of a 2015 study on Canada’s education system, identified the widening success gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners: “It’s one of Canada’s biggest failures in education, which in part dates back to the country’s history of colonialism” (Parkin as quoted in Sachgau, 2015).

Parkin referred to the effects of the residential schools on Indigenous communities: “You’ve got generations of grandparents and parents who were scarred by their experience in education. They’re hardly going to trust that system when it comes to educating their children” (Parkin as quoted in Sachgau, 2015).

Professor Nicholas Ng-A-Fook of the University of Ottawa said that in addition to poor funding for schools, limited access to basic services also creates barriers to achieving a university education: “A kid not having electricity … not having water that they can drink, having to pay two, three or four times more for food, nutritional food, it makes a huge difference” (Ng-A-Fook as quoted in Sachgau, 2015).

Funding and Commitment

The February 2018 federal budget promised a substantial increase in funding for Indigenous communities and it may well be that some of this funding will raise the standard of education for Indigenous children and youth. In the previous federal budget of 2016, the Trudeau government pledged $2.6 billion over five years towards Indigenous education funding. This was an effort “to close the education gap: the difference between INAC funding for on-reserve schools and the funding that occurs through the provincially run public school system” (Morin, 2017a).

Education and child welfare advocate Cindy Blackstock said the federal government is not following through with this commitment.

In 2016, the Parliamentary Budget Officer found significant shortfalls in First Nations education funding even after taking into account the new investments in Budget 2016. Budget 2016 falls far short of what is needed to ensure First Nations students receive an education on par with others. (Cindy Blackstock as quoted in Morin, 2017a)

Many First Nations schools are in such disrepair that they are hazardous to the students, Blackstock added (Morin, 2017a).

Interactive 1.33 Julia Candlish on First Nations education.

Julia Candlish discusses her role at the Chiefs of Ontario, and the advocacy in the area of education, on behalf of the 133 First Nations that the Chiefs of Ontario represents.

Funding Shortfalls

In August 2017 AFN Regional Chief Bobby Cameron noted the following:

In First Nations country we’ve been waiting two, three decades for a K-12 funding increase on reserve and also post-secondary. We’ve been waiting a long time. The governments of the day have played a major role in terms of the delay, in terms of where we are now … at least now we have a government that’s willing and investing.

Teachers are leaving on-reserve schools to teach in the public school system, which offers a more competitive salary. Educational resources like up-to-date text books, libraries, and technology, commonplace items in mainstream schools, are lacking.

Many First Nations children live in poverty and are coming to school hungry. I’m advocating for nutrition programs to be set up, so kids aren’t learning on an empty stomach.

I say we need $20 or $50 billion [for education]. To be honest.

The consequences [if we don’t have the funding] are astronomical because we don’t have students succeeding if they don’t feel good about coming to school, if they’re hungry; lack of self-esteem, lack of pride, self-confidence, falling through the cracks to a negative lifestyle, gangs, alcohol/drugs and the majority of them end up in jail and people taking their own lives. (AFN Chief Bobby Cameron as quoted in Morin, 2017a)

Unsafe Education in Attawapiskat

“I wish I had my whole life to do over just so I could be in a school like this.” – Shannen Koostachin upon visiting a school in Ottawa (Angus, 2015, p. 146)

In Attawapiskat in 2000, J. R. Nakogee Elementary School was forced to close due to contamination from a diesel fuel line that ruptured below the school in 1979 (CBC, 2014a). Throughout the 1980s and 1990s teachers and students at the school had reported on numerous occasions the smell of diesel fuel accompanied by bouts of nausea and headaches (Goyette, 2010). INAC was made aware of the complaints and sent engineers to investigate. In 1984 the fuel leak was confirmed. In 1995 the property was identified as a potentially hazardous site by environmental consultants, and in 1996 Bovar Environmental recommended the removal of the contaminated soil (Goyette, 2010). INAC supported a partial cleanup the following year.

Gallery 1.13 Shannen Koostachin

While this was all taking place, INAC transferred control over curriculum and hiring to Attawapiskat First Nation, but it retained control over funding and capital expenses. No money was provided to move or rebuild the school. Attawapiskat First Nation did not have enough community funding to build a new school itself. Over twenty years Attawapiskat First Nation and INAC spent large sums of money attempting to manage the problem, but never solving it (Goyette, 2010). Finally, in January 2000, Anebeaaki Environmental Inc. deemed the school unsafe for humans due to the contamination. The firm identified five species of mould in the building along with “benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, xylenes and TPH (total petroleum hydrocarbons from gas and diesel) above acceptable levels for human health” in the soil and groundwater (Goyette, 2010). With the support of parents and the community, the chief and council of Attawapiskat First Nation ordered the school closed permanently. Eventually, the school was torn down, and the contaminated grounds fenced off (Goyette, 2010).

The Portable Era in Attawapiskat

In 2000 eleven portable buildings were placed on a dismal and rough strip of land between the contaminated site and the community’s airstrip to serve as a school while families and youth waited for INAC to confirm funding for a new building (Goyette, 2010). For the next 14 years, despite community leaders and youth putting pressure on the federal government to acknowledge their need and rebuild the school, students would attend classes in those portables (Angus, 2012).

Conditions in the portables were drafty and cramped. Students complained about inadequate heating in the winter. In the summer they had no access to outdoor recreational equipment, a playground, soccer field, or baseball diamond (Goyette, 2010). They had to walk to the local community centre to use the gym and between portables to access resources and computers, even in the frigid winter months (Angus, 2012). There was no cafeteria, art space, library, or music facility (Goyette, 2010). Students spoke of black mould and rodent infestations in the portables (Angus, 2012; First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, 2016; Goyette, 2010). Youth who remembered what it was like to go to a “normal” school became disengaged from their education, and the school experienced high absenteeism (Angus, 2012; Goyette, 2010).

After 2000 three successive INAC ministers promised a new school for Attawapiskat, but on April 1, 2008, the Attawapiskat First Nation Education Authority was informed that Ottawa and INAC would not fund the building of a new school (Goyette, 2010). A frustrated community appealed to their Member of Parliament, Charlie Angus, and to southern Canadians to support them in their efforts to demand INAC and the federal government fulfill their obligation to provide safe and comfortable schools for all youth in Canada (Goyette, 2010). Tired of mould, unsafe education, insufficient resources, and watching her community’s youth grow up without the same access to education that other Canadians enjoyed, Shannen Koostachin, a youth from Attawapiskat who had attended school in the portables, joined the fight, and Shannen’s Dream was born.

Shannen’s Dream

Shannen’s Dream is a youth-led campaign focused on advocating for First Nations education and the right to have adequate schools, funding, and other resources in reserve communities. Shannen Koostachin was a smart, passionate, strong, and confident leader who came into her role because she believed that all children in Canada have the right to “safe and comfy” schools. Born and raised in the Attawapiskat community, Shannen turned to activism in grade 8 when the government revealed it would not be funding a new school. She was part of a contingent of elders and community members that met with then Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Chuck Strahl to demand that a decent, healthy elementary school be built for the children of Attawapiskat and other communities like it. At the meeting, Strahl bluntly told the group that building a school was not a priority and ended the meeting. Many of the elders were in tears, but Shannen, determined not to cry, shook his hand and let him know that they were not giving up.

Later that day, Cindy Blackstock, whose organiztion, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, helped create the “Shannen’s Dream” foundation, saw Shannen for the first time and remarked, “I am not religious, but I am very spiritual. I saw Shannen on Victoria Island [in Ottawa], and her power stood out. I didn’t know then that she was going to speak at the rally, but there was something about her. I then saw her on Parliament Hill, and when I heard her speak I was convinced that there was something powerful and spiritual about this young woman. She was a leader” (Angus, 2015, p. 129).

In the months following the 2008 meeting with Strahl, Blackstock became interested in how her organization could help Shannen and her peers. Shannen was tireless in her efforts, and her speech in Ottawa had caught the attention of more than just Blackstock; Canadians, especially teachers and students, began joining the campaign, writing letters, holding their own “Shannen’s Dream” events, and garnering more media attention. The campaign, under the umbrella of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, drew national attention, in large part because Shannen was such a dynamic leader and advocate for Indigenous children’s rights. Tragically, Shannen’s life was ended in a car accident; though she succeeded in pushing for a new elementary school to be built in her community, there was still no high school in Attawapiskat, and she was fatally killed in a collision near Thunder Bay, where she had been living to attend school.

In 2012 the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Attawapiskat First Nation announced that a new school in Attawapiskat would be built at the cost of $31 million (CBC, 2014a). The school, which opened in September 2014, was built to support roughly 540 youth from kindergarten to grade 8 and was named Kattawapiskak Elementary School, for the Cree word for community which translates to “people of the parting rocks” (CBC, 2014a; 2014b). The new school is equipped with computer labs; a cafeteria; science labs; a tech room; a music room; soccer, baseball, hockey, and track fields; a gym; a stadium; and a weight room (Kattawapiskak Elementary School, n.d.). In early January of 2017, classes were cancelled for six weeks after flooding caused significant damage to the flooring (CBC, 2017). More information on current events at Kattawapiskak Elementary School and the Shannen’s Dream campaign can be found on the Kattawapiskak Elementary School website.

References

16×9 on Global. (2015, November). As long as the waters flow. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aDqDKo5nSK8

16×9 on Global. (2016, March 5). Failing Canada’s First Nations children. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhEh-D7IRQc&t=775s

Anaya, S. J. (2009a). International human rights and Indigenous Peoples: The move towards the multicultural state. Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 21.

Anaya, S. J. (2009b). The right of Indigenous Peoples to self-determination in the post-declaration era. In C. Charters, & R. Stavenhagen (Eds.), Making the declaration work (pp. 184-199). Copenhagen: IWGIA.

APTN InFocus. (2017, March). How the housing crisis is causing sickness but also driving solutions. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=91SfDdAuxF4

APTN National News. (2017, March 31). A roof overhead: First Nation housing on the brink of an ‘epidemic’ unless Trudeau gets serious about money. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2017/03/31/a-roof-overhead-first-nation-housing-on-brink-of-epidemic-unless-trudeau-gets-serious-about-money/

APTN National News. (2016, July 12). Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould says adopting UNDRIP into Canadian law ‘unworkable’. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2016/07/12/justice-minister-jody-wilson-raybould-says-adopting-undrip-into-canadian-law-unworkable/

APTN National News. (2018, February 27). Trudeau government announces $1.4B in new funding for First Nation Child Welfare. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2018/02/27/trudeau-government-announces-1-4b-new-funding-first-nation-child-welfare/

A subtle revolution: What lies ahead for Indigenous rights? (2017, September 13). Simon Fraser University VanCity Office of Community Engagement and UBC First Nations and Indigenous Studies Program. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S0su8xD7tfk&t=5407s

Beaumont, H. (2016, October 25). Despite Trudeau’s promise, Liberals haven’t made a dent in the First Nations water crisis. Vice.com. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/kwk59w/despite-trudeaus-promise-liberals-havent-made-a-dent-in-the-first-nations-water-crisis

Blackstock, C. (2017, December 27-31). 15 tips for governments to decolonize [modified with permission]. Via Twitter. @cblackst: #Year151decolonizingtips4government

Browne, R. (2016, June 7). Human Rights Watch slams Canada for water crisis on Indigenous reserves. Vice.com. Retrieved from https://cutoff.vice.com/updates/human-rights-watch-slams-canada-for-water-crisis-on-Indigenous-reserves

Canada endorses Indigenous rights legislation. (2010, November 12). CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canada-endorses-indigenous-rights-declaration-1.964779

Carmen, A. (2010). The right to free, prior, and informed consent: A framework for harmonious relations and new processes for redress. In J. Hartley, P. Joffe, & J. Preston (Eds.), Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Triumph, hope and action. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Ltd.

Cobo, J. R. M. (1981-1983). Study of the problem of discrimination against Indigenous populations (Vol. V). United Nations: Division for Social Policy and Development Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/Indigenouspeoples/publications/2014/09/martinez-cobo-study/

Cut-Off [Documentary]. (2016, June). VICELAND. Retrieved from https://video.vice.com/en_ca/video/cut-off/573e2384e9b4e338637c3678

Deer, K. (2010). Reflections on the development, adoption, and implementation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In J. Hartley, P. Joffe, & J. Preston (Eds.), Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Triumph, hope and action. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Ltd.

Editorial: Indigenous housing crisis takes a terrible toll [Editorial]. (2016, December 19). The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/opinion/editorials/2016/12/19/Indigenous-housing-crisis-takes-a-terrible-toll-editorial.html

Harper, T. (2011, May 30). Afghan mission a ‘great success,’ Harper tells troops in Kandahar. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2011/05/30/afghan_mission_a_great_success_harper_tells_troops_in_kandahar.html

Hartley, J., Joffe, P., & Preston, J. (2010). From development to implementation: An ongoing journey. In J. Hartley, P. Joffe, & J. Preston (Eds.), Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Triumph, hope and action. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Ltd.

Hough, J. (2015, January 1). Ontario professionals volunteer time, money to help remote Ontario First Nation. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/life/2015/01/01/ontario_professionals_volunteer_time_money_to_help_remote_ontario_first_nation.html

Human Rights Commission. (2005). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of Indigenous people, Rodolfo Stavenhagen [UN doc]. E/CN.4/2005/88

Human Rights Council. (2010a). Progress report on the study on Indigenous peoples and the right to participate in decision-making. Report of the expert mechanism on the rights of Indigenous Peoples [UN doc]. A/HRC/15/35

Human Rights Council. (2010b, May). Report of the United Nations seminar on treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements between States and Indigenous peoples [UN doc]. A/HRC/EMRIP/2010/5

International Law Association (ILA). (2010). Rights of Indigenous Peoples committee interim report for the Hague Conference. Retrieved from https://ila.vettoreweb.com/Storage/Download.aspx?DbStorageId=1244&StorageFileGuid=07e8e371-4ea0-445e-bca0-9af38fcc7d6e

Liberal Party of Canada. (n.d.). Truth and reconciliation. Retrieved from https://www.liberal.ca/realchange/truth-and-reconciliation-2/

Littlechild, Chief W. (2010). Consistent advocacy: Treaty rights and the UN Declaration. In J. Hartley, P. Joffe, & J. Preston (Eds.), Realizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Triumph, hope and action. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Ltd.

McCue, D. (2015, October 14). Nazko First Nation asks: why can’t we drink our water? CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-first-nation-drinking-water-1.3271766

Morin, B. (2017a, August 31). First Nations students face continued funding shortfalls, advocate says. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/Indigenous/first-nations-students-face-continued-funding-shortfalls-1.4267540

Morin, B. (2017b, September 13). Where does Canada sit 10 years after the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples? CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/Indigenous/where-does-canada-sit-10-years-after-undrip-1.4288480

Commission on Human Rights, Indigenous Issues. (2004). Note by the Secretariat [UN doc]. E/CN.4/2004/III

Perkel, C. (2016, April 21). Attawapiskat shacks put First Nations housing crisis into perspective. The Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/04/21/attawapiskat-shacks-put-first-nations-housing-crisis-into-perspective.html

Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). (2015, November 12). Jody Wilson-Raybould, official bio. Retrieved from https://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister/honourable-jody-wilson-raybould

Sachgau, O. (2015, September 7). Canada’s education system failing aboriginal students: report. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canadas-education-system-failing-aboriginal-students-report/article26246592/

Steeves, D. (2017, May 7). Pikangium Working Group Presentation. Herriot Visual Communications. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRVpC_T5UcE

Talaga, T. (2017, November 18). “Deaths of 7 Indigenous students in Thunder Bay the responsibility of all Canadians: author.” CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/tanya-talaga-author-seven-fallen-feathers-1.4408984

The Indigenous Bar Association. (2011). Understanding and implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: An introductory handbook. Winnipeg: The Indigenous Bar Association and the University of Manitoba Faculty of Law. Retrieved from http://www.indigenousbar.ca/pdf/undrip_handbook.pdf

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (n.d.). In Indigenous Foundations. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia. Retrieved from http://Indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/un_declaration_on_the_rights_of_Indigenous_peoples/

United Nations. (2007). Frequently asked questions: Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/faq_drips_en.pdf

United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women and the Secretariat of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (2010, February). Gender and Indigenous Peoples, briefing note 1. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/BriefingNote1_GREY.pdf

UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (n.d.). Indigenous languages: Fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/Factsheet_languages_FINAL.pdf

UNESCO. (2001, November 2). UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13179&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

Wilt, J. (2017, December 12). Implementing UNDRIP is a big deal for Canada. Here’s what you need to know. Desmog.ca. Retrieved from https://www.desmog.ca/2017/12/12/implementing-undrip-big-deal-canada-here-s-what-you-need-know

Media (in order of appearance)

United Nations. (n.d.). Chief Wilton Littlechild [Digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2015/09/Wilton-Littlechild.jpg

Soufi, B.D. [photographer]. (2011, April 23). United Nations General Assembly [photograph]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:United_Nations_General_Assembly_Hall_(3).jpg

Cover page of United Nations Declaration Rights of Indigenous Peoples [Digital image]. (2008). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2015/06/undrips-en.png

[CBC News: The National]. (2016, May 9). Canada removing objector status to UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FblRkAFWzgY

[APTN News]. (2017, August 10). Roy-Henriksen Discusses UNDRIP a Decade After Its Adoption | APTN News. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I74XiRGwODU

[HumanRightsWatch]. (2016, June 7). Canada’s Water Crisis: Indigenous Families at Risk. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Arnqpnm70Ng

Indigenous Services Canada. (2018). Long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserve [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ-IH/STAGING/images-images/inf-water-graph_1506515726917_eng.jpg

[CBC News: The National]. (2015, October 14). Water advisories chronic reality in many First Nations communities. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rw5L_rZw3X0

Churches for Freedom Road. (2015). Freedom Road Sign [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://churchesforfreedomroad.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Freedom-Road-sign.jpg

Council of Canadians (n.d.). Image of Shoal Lake No. 40 map [Digital image]. Retrieved from https://canadians.org/sites/default/files/image_0.jpeg

Vice. (2017). Image of Stuart Redsky and Justin Trudeau accompanying Off Trackarticle [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://news2-images.vice.com/uploads/2017/02/shoalloake2.png?crop=1xw:1xh;center,center%20

Hauling water across Shoal Lake in winter [digital image]. (2010, January 8). Retrieved from https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/so-near-so-far-113126539.html

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Amnesty International supports Shoal Lake #40 [digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.ca/sites/amnesty/files/shoallake_facebook2.jpg

[VICE]. (2015, October 8). Canada’s Waterless Communities: Shoal Lake 40. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KHOJ0c2izbo

[APTN News]. (2017, April 3). Housing Crisis Deconstructed | APTN Investigates. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wWYolDlD-x4

[Global News]. (2016, March 5). Full Story: Failing Canada’s First Nations Children. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhEh-D7IRQc

[CBC News: The National]. (2017, November 13). First Nations Families weigh children’s education vs. safety. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9iTBSPSE3U

Centennial College. (2018). Julia Candlish on First Nations education. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/iAV7Zsuv30Y

Unsafe Education in Attawapiskat References

Angus, C. (2012, October 16). Shannen and Serena Koostachin Nov. 2009 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQNvOp6sZDg#action=share

Angus, C. (2015). Children of the broken treaty: Canada’s lost promise and one girl’s dream. Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press.

Media (in order of appearance)

Charlie Angus and Shannen Koostachin [photograph]. (2008). Courtesy of Charlie Angus. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/mp-s-new-book-tells-story-of-girl-who-stood-up-to-ottawa-on-first-nations-education-1.2528292

Koostachin, R. (n.d.). Children in Attawapiskat [Digital image]. Retrieved from http://www.ottawalife.com/admin/cms/images/large/The-children-of-Attawapiskats-call-for-a-new-school_2.jpg

Fauvelle, T. (photographer). (2015). Statue of Shannon Koostachin [photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/shannen-koostachin-honoured-with-statue-in-new-liskeard-ontario-1.3291119

CBCIndigenous. (2014, September 8). “#Attawapiskat school open to students today.1st proper school building in 14 yrs @cbcasithappens Photo:S PaulMartin” [Twitter Post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/CBCIndigenous/status/509148334230347776