7 Environment and Natural Resources

These quotes illustrate two truths. The first eloquently outlines the reality of the deep connection between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional lands. The second reveals the stark despair felt when Indigenous Peoples feel that connection slipping away into the control of forces that do not honour their sacred connection to traditional lands.

There are two other truths that are part of this discussion. One truth is that the natural resources on traditional lands could mean very positive changes to First Nations communities. Many Indigenous leaders agree that their communities’ struggles with employment, health care, safe drinking water, housing, and mental health could benefit from an improvement in their economic circumstances. Many leaders are anxious, if not desperate, to make this happen. Nonetheless, these same leaders are painfully aware that the sacred bond between their peoples and their traditional lands has been broken many times over by governments, mining and forestry companies, and other for-profit organizations that have sought to exploit the natural resources on those traditional lands.

These two truths, then, are opportunity and risk: the opportunity for economic benefits weighed against the risk of damage and destruction to lands, food and water sources, and the very ecosystems that Indigenous Peoples feel part of.

Key Players in Disputes over Traditional Lands and Natural Resources

Indigenous Peoples

The Indigenous Peoples who are the traditional land users are central to any negotiation about land use.

Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Governments

Federal, provincial, and territorial governments may all have a role to play in negotiations and consultation.

While some argue that the Canadian federal government has been reasonably progressive in recognizing Indigenous land and resource rights, such recognition has often come only after lengthy court battles and relentless pressure by Indigenous communities (Anderson, Schneider, & Kayseas, 2008). Unfortunately, when governments must be forced by the courts to honour Indigenous land rights, one cannot expect these same governments to intervene fairly when private sector organizations wish to profit from resources on traditional lands.

Private Sector Industries

When natural resources such as lumber, minerals, or fossil fuels become a focus for industry, companies that stand to gain economically from the development of such resources are key participants in negotiations.

In November 2014, First Peoples Worldwide released its report on the tension between “extractive industries” and Indigenous land rights. The Indigenous Rights Risk Report studied 52 oil, gas, and mining companies undertaking 330 projects worldwide. The study found that 92 percent of the companies (48 out of 52) “do not address community relations or human rights at the board level in any formal capacity” (Adamson, 2014).

Interactive 1.23 Short documentary about the Ring of Fire:

This documentary features a nurse practitioner who works with community members who face challenges in becoming effective negotiators and decisions makers in the Ring of Fire.

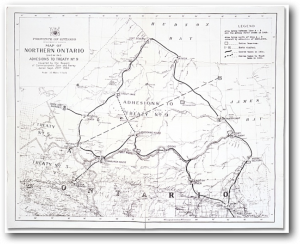

The Ring of Fire

Students are encouraged to explore examples of how Indigenous Peoples have advocated – with a wide range of outcomes – for full consultation, economic benefit–sharing, and protection of traditional lands through the summaries in the sidebars.

One story, the Ring of Fire, is examined here in more detail. The outcome is not yet known as events are ongoing at the time of writing.

The Ring of Fire is the common reference for a section of Northern Ontario, roughly 240 kilometres west of Attawapiskat, covering almost 10,000 square kilometres and containing some 5300 mining claims as of mid-2016. Over 24,000 Indigenous Peoples call these their traditional lands. These communities “depend on wild fish and animals for food and have inherent [treaty] rights to the land. This wilderness of trees, wetlands, lakes and rivers is part of the planet’s largest intact forest. It supports hundreds of plant, mammal and fish species, most in decline elsewhere, and is the continent’s main nesting area for nearly 200 migratory birds” (Wildlands League, n.d.).

Matawa First Nations Management

The First Nations of these traditional lands are largely, but not exclusively, represented by Matawa First Nations Management (MFNM), also known as the Matawa Tribal Council. MFNM was established in 1988 as a tribal council with nine member Ojibway and Cree Nations. While each of these nine First Nations retain the right to negotiate with industry and governments independently, they also understand the power of solidarity in negotiations with the Ontario government (Freeman, 2013b). The nine member Nations are: Aroland First Nation, Constance Lake First Nation, Eabametoong First Nation, Ginoogaming First Nation, Long Lake #58 First Nation, Marten Falls First Nation, Neskantaga First Nation, Nibinamik First Nation, Webequie First Nation.

Complex Negotiations

The Matawa Tribal Council has been involved in high-stakes negotiations regarding the development of this region since approximately 2010. These “First Nations are under pressure from mining companies and the province to consent to complex agreements to move the project forward” (Freeman, 2013b).

Three of these First Nations – Webequie, Marten Falls, and Neskantaga (also known as Lansdowne House) – have overlapping claims to land they each consider their traditional territory. Knowledge keepers tell tales of how the area has been an ancient meeting ground for members of neighbouring bands. For the first time in generational memory, there is a need to define borders around “traditional territory that was once seen as shared land” (Freeman, 2013b).

Indigenous representatives are well aware of the disastrous history of for-profit organizations attempting to strike it rich by exploiting natural resources on traditional lands. The damage to lands, food sources, community health, and communities in general has been extreme. (See sidebars.)

Sidebar 1: The Grassy Narrows Tragedy

From 1962 to 1970 the Dryden pulp and paper mill dumped 10 tons of mercury into the Wabigoon-English River system, poisoning the ecosystem and the residents of Grassy Narrows. The river and lake systems were contaminated for at least 250 km downstream (Bruser, 2016).

[Mercury] does not break down in the environment and can build up in living things, […] “inflicting increasing levels of harm on higher order species,” according to Environment and Climate Change Canada. Bacteria […] turn mercury into its most toxic form, methylmercury. The methylmercury migrates up the food chain to fish and then to the locals who eat the fish. Absorbed through the digestive tract, methylmercury “readily enters the brain” where it can remain for a long time, according to Health Canada. In a pregnant woman, it can build in the fetal brain and other tissues. (Bruser, 2016)

In the 1960s residents started to notice dead fish floating to the surface. Turkey vultures began to fly as if they were drunk. Fish-eating mammals, such as the otter and mink, disappeared. The locals were told to stop eating the fish (Bruser, 2016). The robust fishing tourism industry, especially at famous Ball Lake Lodge, was decimated. Commercial fishermen and guides went on welfare (Bruser, 2016). “You can’t see the mercury, but we know it’s in there,” said Judy Da Silva in an interview in 2016. “Being a land-based people and a river people historically, it has been devastating through time” (Draaisma, 2016). Her whole life, DaSilva has been dealing with the fallout of the mercury contamination. “I have mercury poisoning. It affects me physically. I was in my mother’s womb when the poison was being poured into the river.” The poisoning has robbed the community of its way of life, she said. People have to live on welfare to survive (Draaisma, 2016).

Sidebar 2: Lac La Ronge Indian Band and Kitsaki Management

Located in Northern Saskatchewan, the Lac La Ronge Indian Band (LLRIB) is the largest First Nation in Saskatchewan and one of the 10 largest in Canada. In 1981 the LLRIB formed the Kitsaki Development Corporation, which later evolved into the Kitsaki Management Limited Partnership (KMLP), to manage for-profit economic development on traditional lands. The KMLP’s approach to improving the socio-economic circumstances of the people of the LLRIB has been to form “sound, secure partnerships with other Aboriginal groups and successful world-class businesses in order to generate revenue for Kitsaki and employment for Band members” (McKay, 2002, p. 3). Employment rates and overall quality of life for band members has increased substantially while traditional lands have been protected.

Sidebar 3: The Tar Sands of Northern Alberta

In the late 1950s and early 1960s the Alberta government assured impoverished First Nations’ band councils that the development of their treaty reserve lands, which included the tar sands, would create economic development and jobs for their communities. This assurance led to the first experiments with tar sands operations in the 1960s and 1970s on lands inhabited mostly by Dene, Cree, and Métis. Exxon, Shell, Syncrude Canada, BP/Husky, CNRL, and Suncor Energy used explicit public relations campaigns targeting First Nations communities to advocate for how tar sand expansion would be good for Indigenous Peoples (“What Are the Tar Sands,” n.d.).

In 2015-2016 a review of the Lower Athabasca Regional Plan (LARP) revealed that the Alberta government failed to protect Indigenous rights, lands, and health from industrial development in the tar sands region (Weber, 2016). “What Alberta said it would do and what it actually did are very different things,” says the review panel report. The inquiry report agreed with the Athabasca Chipewyan, the Mikisew Cree, the Onion Lake Cree, the Chipewyan Prairie Dene, and the Cold Lake First Nations that business was given priority over Indigenous constitutional rights (Weber, 2016).

On their webpage “What Are the Tar Sands,” the Indigenous Environmental Network notes the following:

- Loss of fresh water: Tar sands operations are licensed to divert 652 million cubic metres of fresh water each year, 80 percent from the Athabasca River. In comparison, this amounts to approximately seven times the annual water needs of the city of Edmonton.

- Loss of fish and animal habitat: About 1.8 million cubic metres of this water becomes highly contaminated with toxic tailings waste each day.

- Cancers and other health issues: In 2006 unexpectedly high rates of rare cancers were reported in the community of Fort Chipewyan. In 2008 Alberta Health confirmed a 30-percent rise in the number of cancers between 1995-2006. However, the study lacks appropriate data and is considered a conservative estimate by many residents.

- Loss of caribou and other traditional food sources: Caribou populations have been severely impacted by tar sands extraction. The Beaver Lake Cree First Nation has experienced a 74-percent decline of the Cold Lake herd since 1998 and a 71-percent decline of the Athabasca River herd since 1996. By 2025 the total population is expected to be less than 50 and locally extinct by 2040.

(“What Are the Tar Sands,” n.d.)

References

Adamson, R., & Pelosi, N. (2014). Indigenous Rights Risk Report. First Peoples Worldwide, Inc.

Anderson, R., Schneider, B., and Kayseas, B. (2008). Indigenous Peoples’ land and resource rights. Unpublished research paper submitted to the National Centre for First Nations Governance.

APTN National News. (2011, March 8). Ring of Fire battle lines lit. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2011/03/08/ring-of-fire-battle-lines-lit/

APTN National News. (2014, April 24). Special ceremony marks beginning of Ring of Fire framework. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2014/04/24/special-ceremony-marks-beginning-ring-fire-framework

Assembly of First Nations. (2012). Assembly of First Nations reiterates support for Matawa Chiefs while attending Back to Our Roots Gathering III; Free prior and informed consent required. Retrieved from http://www.afn.ca/2012/11/06/assembly-of-first-nations-reiterates-support-for-matawa-chiefs-while-a/

Barrera, J. (2017, August 25). Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne cut “backroom” Ring of Fire deals: Chief. APTN National News. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2017/08/25/ontario-premier-wynne-cut-backroom-ring-of-fire-deals-chief/

Bruser, D. (2016, July 24). Star Investigation: A poisoned people. Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/07/24/disability-board-approves-mercury-poisoning-claims-from-grassy-narrows-first-nation.html

CBC News – Thunder Bay. (2013, May 10). Bob Rae to lead First Nations in Ring of Fire negotiations. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/bob-rae-to-lead-first-nations-in-ring-of-fire-negotiations-1.1311892

Curry, B. (2016, August 26). Road to Ring of Fire could cost up to $550 million. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/road-to-ring-of-fire-could-cost-up-to-550-million/article31585443/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

Deibert, D. (2017, June 13). Two children doused in gasoline, set on fire on Lac La Ronge First Nation: EMS. Saskatoon StarPhoenix. Retrieved from http://thestarphoenix.com/news/local-news/two-children-hospitalized-one-in-la-ronge-one-in-saskatoon-after-altercation-with-third-child

Draaisma, M. (2016, June 2). Time to clean up river in Grassy Narrows First Nation, grandmother says. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/grassy-narrows-river-mercury-poisoning-cleanup-1.3612553

Environmental Commissioner of Ontario. (2013). Danger ahead for the Ring of Fire. Retrieved from https://media.assets.eco.on.ca/archive/2015/03/2012-13-AR-Ring-of-Fire.pdf

Echum, C. (2013). Chief of the Ginoogaming First Nation, speaking at the Matawa First Nations Gathering, Thunder Bay. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPbl0IpULHk&t=39s

Freeman, S. (2013a). Canada, Aboriginal tension erupting over resource development, study suggests. Huffington Post Canada. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/10/30/canada-aboriginals-resource-development_n_4178464.html

Freeman, S. (2015). Ontario’s Ring of Fire, formerly ‘The Next Oilsands’, sold for peanuts. Huffington Post Canada. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/03/23/ring-of-fire-ontario-noront-cliffs_n_6923110.html

Freeman, S. (2013b). Ring of Fire negotiations: Bob Rae must turn legacy of failure into hope for future. Huffington Post Canada. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/10/07/staking-claim-3_n_4045078.html?utm_hp_ref=ca-first-nations-ring-of-fire

Groves, T. (2012). First Nations oppose the Ring of Fire mining projects. Toronto Media Co-Op. Retrieved from http://toronto.mediacoop.ca/story/first-nations-oppose-ring-fire-mining-projects/11622

Jones, A. (2017, August 21). Ontario to move ahead with road access into chromite-rich Ring of Fire region. The Canadian Press. Retrieved from http://www.680news.com/2017/08/21/ontario-to-move-ahead-with-road-access-into-chromite-rich-ring-of-fire-region/

Lac La Ronge (All Saints) Indian Residential School. (n.d.). Shattering the silence: The hidden history of Indian Residential Schools in Saskatchewan [eBook]. Retrieved from http://www2.uregina.ca/education/saskindianresidentialschools/lac-la-ronge-all-saints-indian-residential-school/

MacKay, F. (2004). Indigenous Peoples’ right to free, prior, and informed consent and the World Bank’s extractive industries review. Sustainable Development Law & Policy (Vol. IV, Issue 2).

Martell, C. (2016, October 17). Deaths in Lac La Ronge Indian Band have community searching for solutions. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/youth-suicides-in-lac-la-ronge-indian-band-has-community-reeling-1.3808254

Matawa First Nations Management (MFNM). (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from http://www.matawa.on.ca/aboutus/

Matawa First Nations. (2011). The Ring of Fire. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZod1E3a548

Matawa First Nations Gathering. (2013). The power of unity and the dignity of difference. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPbl0IpULHk&t=24s

Morin, B. (2016). Alberta violates Aboriginal and Treaty rights in tar sands region: report. APTN. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2016/02/17/alberta-violates-aboriginal-and-treaty-rights-in-tar-sands-region-report

Mulligan, C. (2015, December 3). Province dinged on ‘Ring of Fire.’ The Sudbury Star. Retrieved from http://www.thesudburystar.com/2015/12/03/province-dinged-on-the-ring-of-fire

Nursall, K. (2013). War in the Woods mass arrests 20 years ago prompted lasting change. The Canadian Press. Retrieved from http://bc.ctvnews.ca/war-in-the-woods-mass-arrests-20-years-ago-prompted-lasting-change-1.1406602

Office of the Premier of Ontario. (2015). First Nations, Ontario sign political accord. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2015/08/first-nations-ontario-sign-political-accord.html

Ortiga, R. R. (2004). Models for recognizing Indigenous land rights in Latin America. The World Bank. Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

“Parents on edge after northern Saskatchewan suicides.” (2016, November 2). CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/community-response-northern-saskatchewan-suicides-1.3831863

Porter, J. (2014, October 15). Three big ‘whoppers’ told about the Ring of Fire. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/three-big-whoppers-told-about-the-ring-of-fire-1.2795449

Scales, M. (2017). Noront’s road to the Ring of Fire. Canadian Mining Journal. Retrieved from http://www.canadianminingjournal.com/features/noronts-road-ring-fire/

Tencer, D. (2013). Clement: Ontario ‘Ring of Fire’ will be Canada’s next oil sands. Huffington Post Canada. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/04/26/ring-of-fire-ontario-tony-clement_n_3159644.html

Weber, B. (2016). Alberta failing Aboriginal people in the oilsands area: report. The Canadian Press. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/alberta-failing-aboriginal-people-in-the-oilsands-area-report-1.3430762

“What are the tar sands.” (n.d.). Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN). Retrieved from http://www.ienearth.org/what-are-the-tar-sands/

Wildlands League. (n.d.). Ring of Fire. Retrieved from http://wildlandsleague.org/project/ring-of-fire/

Windigo, D. (2013, October 11). ‘It’s bad for the environment, if we are not careful, it’s bad for First Nations’. APTN National News. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2013/10/11/its-bad-for-the-environment-if-we-are-not-careful-its-bad-for-first-nations/

Windigo, D. (2014, October 1). Ring of Fire chiefs demand Ontario walk the partnership talk. APTN National News. Retrieved from http://aptnnews.ca/2014/10/01/ring-fire-chiefs-demand-ontario-walk-partnership-talk/

Younglai, R. (2013, November 20). Cliffs Natural Resources calls off Ring of Fire mining project. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/cliffs-natural-resources-to-halt-ring-of-fire-development/article15539036/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&