4.3 Hazard Recognition

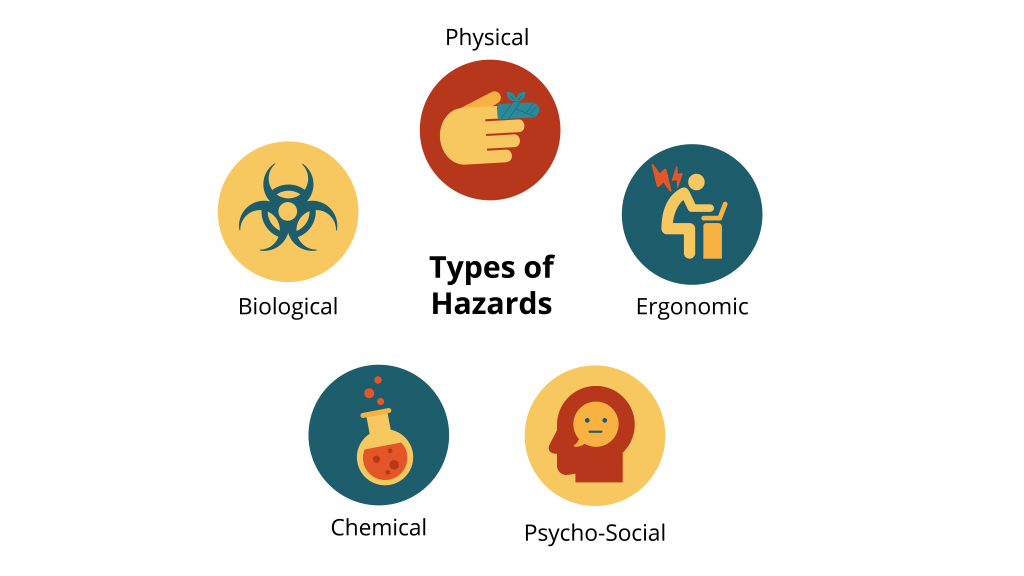

The HRAC process starts with comprehensively identifying all the hazards in a workplace. The five categories of hazards include physical, ergonomic, chemical, biological and psycho-social. Let’s review each one in detail.

- Physical hazards typically entail a transfer of energy from an object, such as a box falling off a shelf, which results in an injury. These are the most widely recognized hazards and include contact with equipment or other objects, working at heights, and slipping. This category also includes noise, vibration, temperature, electricity, atmospheric conditions, and radiation. All of these hazards can create harm in certain contexts.

- Ergonomic hazards occur as a result of the interaction of work design and the human body, such as work-station design, tool shape, repetitive work, requirements to sit/stand for long periods, and manual handling of materials. Ergonomic hazards are often viewed as a subset of physical hazards. For the purposes of hazard assessment, it is useful to consider them separately because they are often overshadowed by more obvious physical hazards.

- Chemical hazards cause harm to human tissue or interfere with normal physiological functioning. The short-term effects of chemical hazards can include burns and disorientation. Longer-term effects of chemical hazards include cancer and lead poisoning. While some chemical substances are inherently harmful, ordinarily safe substances can be rendered hazardous by specific conditions. For example, oxygen is essential to human life, but in high doses can be harmful.

- Biological hazards are organisms—such as bacteria, molds, funguses—or the products of organisms (e.g., tissue, blood, feces) that harm human health.

- Psycho-social hazards are social, environmental, and psychological factors that can affect human health and safety. These hazards include harassment and violence but also incorporate issues of stress, mental fatigue, and mental illness.

Recognizing each type of hazard requires different methods and approaches. Analyzing each category of hazard separately allows us to consider the specific issues associated with the category. There are many ways to identify hazards in a workplace. There are many companies and consultants offering commercial hazard assessment packages to employers for a fee. The pre-prepared packages can help establish a framework upon which to build. There are also free resources available from reliable organizations, such as the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety which allow the hazard assessment process to be tailored to specific workplaces. A common feature of robust hazard recognition systems is that they examine the workplace from multiple perspectives to ensure that all hazards are identified.

It is useful to start the hazard assessment process by considering the nature of the work and workplace. The context of work affects the type of hazards in the workplace. For example, recognizing that work takes place at a remote workplace—such as a tree-planting operation or oil-field drilling site—raises issues of emergency response times, travel hazards, and working alone. Similarly, if workers are hired on a part-time or temporary basis, this may affect communication and training. Vulnerable workers—such as newcomers to Canada or youths—may be reluctant to identify hazards for fear of losing their jobs. These examples demonstrate that hazards do not merely reside in the task of working but also in the wider context of the employment relationship. One of the common omissions in hazard recognition is ignoring the underlying factors that lead to the creation of hazards. A narrower scope of recognition fits the employer’s interests in limiting safety to proximate causes but it can undermine the effectiveness of the HRAC process.

Hazard Identification Techniques

There are a variety of hazard-identification techniques, and these are often used in combination to create a fuller picture of a workplace’s hazards:

- Inspecting the workplace: Physically observing the workplace and how work is performed within it is a powerful step in identifying hazards. The inspection should not be limited to considering physical objects, such as machines, tools, equipment, and structures, but should also include observing processes, systems, and work procedures.

- Talking with workers: Passive observation can miss many important aspects of how work is performed. Getting the perspective of the people conducting the work will reveal other insights. This can be done informally through discussions or through more formal means such as surveys or interviews.

- Job inventory: Acquiring job descriptions and specifications can also reveal hazards. Mapping out the flow of work to create a task analysis allows for a systematic examination of how a job is supposed to be conducted. It is important to compare this data with worker interviews to identify instances where work practices differ from formal procedures.

- Records and data: Reviewing records of previous workplace incidents, safety reports, and other documentation can yield useful information about the hazards in a workplace.

- Measuring and testing: Sometimes, to discover if something is a hazard, you will need to measure or test it. This is particularly true for noise, chemical hazards, and biological hazards.

- Research: Knowing something is present in the workplace may be insufficient to determine if it is a hazard. You may need to conduct research on a substance, material, design, or environment to assess its potential for harm.

The hazard identification process must be carefully documented. Hazard identification forms should break the identified hazards into their main types as well as by work area, job, or process performed. There are many generic forms available online. It will be necessary to adapt these to reflect the nature of the work and the workforce.

“Hazard Recognition, Assessment, and Control” in Health and Safety in Canadian Workplaces by Jason Foster and Bob Barneston, published by AU Press is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, unless otherwise noted.