28 7.2 – History of FMT & Methods of Treatment

History of Fecal Microbiota Transplant

It has been suggested that Fecal Microbiota transplants were first used in veterinary medicine by the Italian anatomist Fabricius Aquapendente in the 17th century. However, it has been found that the treatment appeared first in the Chinese handbook of emergency medicine, “Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang” (or “Handy Therapy for Emergencies”) (Brandt et al.).

In the 16th century, Li Shizhen wrote about possible treatments in similar medicine handbook. The prescribed treatment entailed using “fermented fecal solution, fresh fecal suspension, dry feces, or infant feces for effective treatment of abdominal diseases with severe diarrhea, fever, pain, vomiting, and constipation”. Amusingly, this treatment was labelled “yellow soup” (F. Zhang et al.).

Modern medicine, however, uses enemas, nasogastric intubation, enteric intubation, colonoscopes, and gastroscopes for fecal administration (Brandt et al.).

For the last 50 years FMT has begun to be used in modern medicine. Epidemics like Clostridium difficile infection have resulted in an increase use of FMT. This treatment has been shown to be highly effective in treating C. Difficile infection and its symptoms (Borody and Khoruts). The success of FMT treatment has not as of yet been shared by Chron’s disease.

Methods of Treatment

The goal of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in treating Chron’s Disease is to alter the fecal microbiome of the patient by reducing the dysbiosis of the bacterium that may be inducing pro-inflammation (Suskind et al.).

Differences to patient microbiota have been observed between healthy patients and those with Crohn’s disease. It is not yet certain whether the symptoms observed in a Chron’s disease patient are due to the disease or due to the patient’s microbiota being in a state dysbiosis.

Perhaps due to the severity of the Crohn’s Disease, many studies are looking to study the disease and its relationship with FMT through small clinical trials where the controls for the study are limited.

Such a study was conducted by Zhang and colleagues to try to use FMT to induce and retain clinical remission of Chron’s Disease (He et al.).

Patients were recruited into the study if they to be between 18 to 70 years old with moderate to severe cases of Chron’s Disease. This was established by the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI). MRIs were used prior to the FMT to identify the intra-abdominal inflamed masses.

There were several exclusion criteria:

- If patients had other serious diseases (for instance, a C. Difficile infection or cancers)

- Patients with refractory obstruction symptoms

- Patients who have received biological therapies and had unclear clinical responses three months prior to FMT.

The stool for the transplantation was collected and screened from healthy donors aged 10-25 years old. The donors were screened to ensure no antibiotics, laxative or diet pills were consumed in the last three months and that the donors had no history of serious illness and no recent gastrointestinal diseases. Specifically, any disease with the potential to alter the gut microbiome. The stools were then tested for C difficile bacteria, ova and parasites.

Once the donor stools were acquired, the FMT treatment was able occur. One week prior to treatment, all conventional anti-inflammatory treatment (antibiotics, steroids etc) of Chron’s disease was ceased and patients were given 3.0g of Mesalazine for daily intake. This was taken daily for three months and then reduced to 1.5g. While Mesalazine usually has a limited benefit in such severe cases of Chron’s disease, but it was administered here to provide an anti-inflammatory effect for patients after the FMT procedure, if they can achieve remission.

Prior to the treatment, baseline data was collected such as how long the patients had the disease for, the location, the behaviour of the disease, prior treatments and surgical history. Stool and blood samples were also collected along with measuring the patient’s Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI).

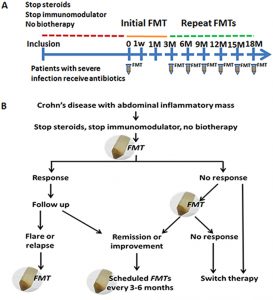

Once the transplant was ready to occur, the initial fresh FMT was put into the patient’s midgut while they were under anesthesia. Patients then performed clinical assessments every one week, three weeks and then every three months after the initial FMT (Figure 1). The study was considered finished when a patient achieved sustained clinical remission for 12 months. However, a secondary endpoint was considered if there was a decrease in the size of the abscess in the prior location.

If patients showed a positive response to the first FMT, they were scheduled to receive further FMT treatments with the regularity of 3 months. If a patient did not respond to the first treatment, they were encouraged to conduct a secondary transplant within 7 days. If there was a flare up or remission of Chron’s disease, inflammation markers and the patient’s HBI score were monitored. For those who failed to achieve remission could switch over to another more traditional therapy.

In the next chapter, we shall examine this study in further detail.

Question:

What was the role of Mesalazine in FMT treatment? Why was it administered a week prior?