4.4 – Using iMSCs to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Disease

In this section, a recent paper exploring the possibility of using induced mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs) to treat Inflammatory Bowel Disease will be highlighted along with implications of these results. The paper is titled:

“Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC) Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSC) Equivalent to Adipose‐Derived MSC in Promoting Intestinal Healing and Microbiome Normalization in Mouse Inflammatory Bowel Disease Model” (Soontararak et al., 2018)

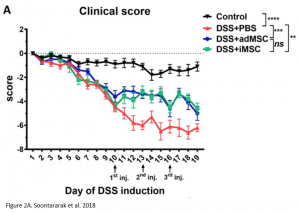

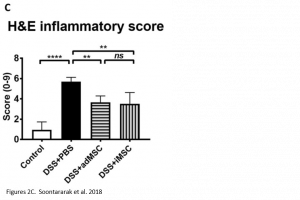

In this paper, the use of induced mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs) as a potential treatment for IBD was evaluated in comparison with treatment using adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells (adMSCs). To study the effects of both intervention, mice with induced colitis were used as a model. This involved a 19-day long experiment in which mice were induced with colitis on day 1 of the experiment and received treatments on day 10, 13, and 16. The treatment groups include: mice with colitis + no treatment (DSS + PBS), mice with colitis + iMSC treatment (DSS +iMSCs), mice with colitis + adMSC treatment (DSS+adMSC), and healthy controls. Clinical signs of colitis and gut microbiome composition were compared between the groups.

Researchers found that treatment with iMSCs resulted in improved clinical scores, indicating that symptoms of colitis had declined over the period of treatment. Furthermore, when looking at histological samples of the colon, a decrease in inflammation was observed in iMSC treated mice. The improvements observed were comparable with treatment using adMSCs.

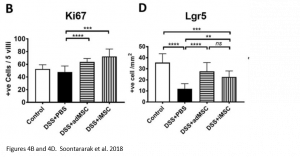

At the molecular level, it was noted that iMSC treatment was associated with an increase in proliferation of cells (indicated by Ki67 marker) as well as an increase in intestinal stem cells (indicated by Lrg5 marker). These markers indicate that changes leading to improved colitis were happening at a molecular level as well.

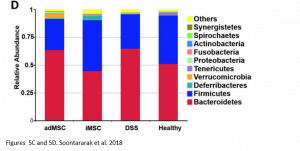

Remarkably, when comparing the gut microbiome of healthy mice, mice with colitis, and iMSC treated mice with colitis, the authors also saw that iMSCs was best able to restore the gut microbiome composition to that of the healthy controls. In this case, iMSCs were better than adMSCs at restoring the microbiome composition. However, this observed benefit is only a correlation and no causal relationship can be established yet.

Since improvements were seen at the phenotypic and molecular level, it was expected that majority of the injected iMSCs localized to the colon. However, this was not the case for both the adMSC and iMSCs. When the MSCs were fluorescently tagged and tracked for 72 hours, it was observed that only a small population localized to the colon – the rest dispersed between the lung, liver, and spleen. This suggests that the improved outcomes in the mice are not due to MSCs alone but are also influenced by possible paracrine factors that MSCs secrete. This is in line with existing literature, which suggests that MSCs secrete exosomes carrying microRNAs (miRNAs) and other transcription factors and cytokines that have immunomodulatory effects (Crevelli et al.). Further investigations would be required to confirm this hypothesis.

EXOSOMES

- are microvesicles secreted from the extracellular matrix of many cells

- circulate in biofluids (i.e. blood) and contain various proteins and factors involved in cell to cell communication

microRNAS

- are short non-coding regions of the genome that can modulate gene expression post-transcriptionally through blocking and degrading mRNAs

- are responsible for the regulation of many cellular functions

- abnormal levels of miRNAs have been associated with various diseases

Overall, results from this paper suggest that the use of iMSCs as a treatment is not only comparable to MSCs derived from adipose, but also in a sense better. Not only do iMSCs provide a more stable source of cells (as mentioned in the previous chapters), but they may also beneficially alter the gut microbiome. While the results are promising, this is only the tip of the iceberg. Many questions still remain about the mechanism of action of the iMSCs as well as its long-term efficacy.

- What are specific mechanisms of action for the MSC treatment? Does it act in a solely paracrine fashion?

- What is the correlation between iMSCs and the microbiome composition? Are improved microbiome composition a result or iMSC treatment or is the treatment effective due to an improved microbiome composition?

- Are the therapeutic effects of iMSC in IBD durable?

Moving forward, research towards answering these questions must be completed before iMSCs can be used as a treatment in clinical settings.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- iMSCs are just as effective as adMSCs in treating colitis in mice

- In mice with colitis, treatment with iMSCs led to improved clinical score, decrease inflammation, increased intestinal stem cell population, and restored gut microbiome composition

- iMSCs did not localize to the colon, thus they may act in a paracrine fashion

- MSCs secrete exosomes containing miRNAs that may regulate inflammation and improve symptoms of colitis

TEST YOURSELF

Critical Analysis Question:

What is a possible experiment that can be conducted to determine the mechanism of action of iMSCs in inflammatory bowel disease? (For possible solution, see here)