4.1 – Overview of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the chronic inflammation of the digestive tract. It has a global prevalence of 1 in 350 people, with increased prevalence in northern regions (Molodecky et al.; Ng et al.). For example, 1 in every 150 Canadians is afflicted with IBD. As a point of comparison, IBD is twice as common as Multiple Sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease, and approximately as prevalent as Type 1 diabetes or epilepsy (What Are Crohn’s and Colitis? – Crohn’s and Colitis Canada). Since IBD is a chronic condition, its recurring symptoms can interfere with an individual’s daily life and impact families in unexpected circumstances.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Both forms of IBD also exhibit a set of trademark overlapping symptoms. This includes stomach pain, change in bowel habits or consistency (more urgent movements and diarrhea), weight loss, decreased appetite, fever, and fatigue (Ungaro et al.). As a key characteristic of a chronic condition, symptoms of IBD can come and go. People who are afflicted can undergo flare ups—in which high symptom presentation and pain result—as well as remission, in which no symptoms are presented. Less common symptoms also include inflammation in the eyes, skin, liver and joints (Isaacs). The assessment of these symptoms are paired with measurements of blood samples and stool samples for the diagnosis of IBD. Furthermore, X-rays along with endoscopy or colonoscopy, are used to survey the interior of the bowel to help determine the extent and type of IBD as well. Diagnosis usually occurs in the earlier years of life, between 15 and 25 years of age (Johnston and Logan). Moreover, the risk of diagnosis can be slightly higher for those who have family members afflicted with IBD (Torres et al.; Ungaro et al.).

The two types of IBD: Ulcerative Colitis and Chron’s Disease

There are two forms of IBD—ulcerative colitis (UC) and Chron’s disease (CD)—which differ based on their biological presentation. Ulcerative colitis is the continuous inflammation in the mucosa, the innermost layer of the colon. Given that the inflammation occurs specifically in the mucosal layer, mucus and blood may come in direct contact with bowel movements (Podolsky and Isselbacher). Thus, mucous and blood in the stool are a common symptom. While surgery to treat ulcerative colitis is sometimes inevitable, it is often avoidable through early treatment of UC.

Alternatively, Chron’s disease involves sporadic inflammation, where there are groups of small ulcers. These ulcers are larger and deeper based on severity. Contrary to ulcerative colitis, which only affects the mucosal layer of the colon, Chron’s disease affects all layers of the intestinal wall throughout the gastrointestinal tract (Torres et al.). This inflammation thickens the lining of the gut, causing blockage and difficulty in moving digested food. Thus, blood in the stool may be presented as a symptom, but is often also accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Sometimes, the deep ulcers will break through the lining of the intestine, which causes infection outside the bowel. This is called an abscess, which can spread to the skin or another nearby part of the body, forming a fistula (as described in the video below). Given these complications, 3 out of 4 patients with Crohn’s will require surgery to remove an inflamed section, as a result of blockage, of the digestive system (What Are Crohn’s and Colitis? – Crohn’s and Colitis Canada; DocMikeEvans).

(NationwideChildrens)

Causes of IBD

Although the causes behind IBD are not entirely known, studies show that the root of the disease is generally due to the immune system malfunctioning to attack its own healthy tissue inside the digestive system, resulting in inflammation. Studies show that IBD can from multiple mechanisms, including changes in innate immunity and intestinal barrier defects.

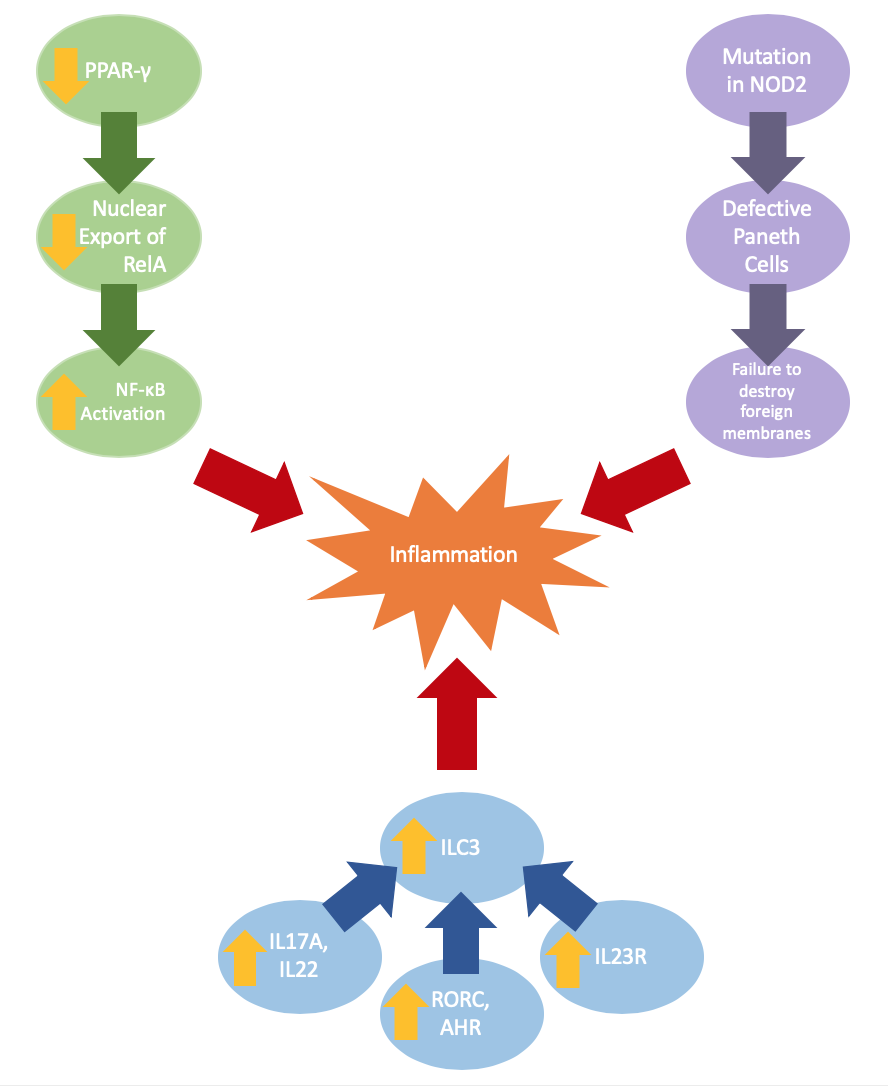

Intestinal barrier defects can be a result of changes in gene expression or gene mutation. Ulcerative colitis may be caused by reduced expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), which negatively regulates NF-κB-dependent inflammation. The lowered expression of PPAR-γ yields a decrease in nuclear export of RelA, which increases coding transcription factors activating NF-κB, a complex that can increase inflammation (Jiang et al.).

Crohn’s disease is often paired with a mutation in the NOD2 gene, which results in defective Paneth cells that do not produce adequate α-defensins, which are antimicrobial peptides; the reduction of these α-defensins impairs innate abilities to breakdown foreign membranes (Wehkamp et al.). Current studies also indicate changes in innate immunity through the increased expression of cytokines (IL17A, IL22), transcription factors (RORC, AHR), cytokine receptor IL23R (Geremia et al.). These expressions result in an increase of ILC3, a major mediator of chronic intestinal inflammation.

Furthermore, changes in microbiome are common for IBD as well. While more significant for Chron’s disease than ulcerative colitis, both present lower proportions of Firmicutes as well as higher proportions of Gammaproteobacteria and Enterbacteriaceae (Frank et al.). It is unclear whether these microbiome alterations are the cause or the result of IBD.

Current treatment options

Unpredictable flare-ups can severely affect physical, emotional, and social factors in a variety of settings both within and outside of one’s home (Kemp et al.). Given that there is not yet sufficient research into a cure for IBD, current treatment options are centered around reducing flare-ups and increasing the duration of remission. This may involve anti-inflammatory drugs as well as immune-suppressants. However, given the varying symptoms between individuals and the uncertainty of the exact mechanisms causing these variations, the use of these treatment options may not always produce outcomes through the expected pathways of immunity (Scribano). Thus, further research focuses on an alternative treatment that may be able to reduce these side effects and better target the healing of the intestinal wall layers, the trademark among symptoms in every IBD patient.

An emerging treatment is cellular therapy, which involves transferring healthy human cells in an effort to address damaged tissues and cells. Forms of cellular therapy, particularly with the use of stem cells, has shown promise in other diseases (Ranganath et al.). As discussed and explained further in the rest of this chapter, the key research question to be asked is whether cellular therapy of any form can be used as a sustainable therapy for IBD.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) has many symptoms, including fever, weight loss, and changes in bowel habits

- IBD can take the form of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease

- While both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease share trademark symptoms of IBD, they also have more specified characteristics

- The causes of IBD have not been fully elucidated, but many mechanisms indicate changes in innate immunity and barrier defects

- An emerging treatment of IBD is cellular therapy