9.5 Humanitarian Logistics

Learning Objective

4. Introduce the concept of Humanitarian Supply Chain Management.

Humanitarian Supply Chain Management

Disasters occurring across the world pose a severe threat to human society. Disasters may be natural (heavy rainfall, avalanches, earthquakes) or human made (industrial accidents, chemical leakages, building collapses) in nature (Maqbool & Khan, 2020). During and after the disaster, the provision of relief and recovery materials lowers victims’ suffering. In such a situation, the supply chain network plays a crucial role.

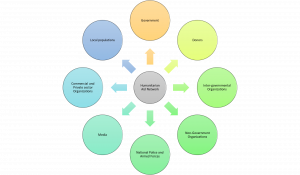

Providing the “right materials” in the “right quantity” to the “right people” at the “right time” is the intention of typical supply chain management (SCM) (Sharma & Luthra, 2020). It is applicable for both commercial and humanitarian SCM (HSCM). In comparison with commercial supply chain management, the number of challenges in HSCM is greater (Barcik, Beamon, Krejci, Muramatsu & Ramirez, 2010). This is because HSCM is carried out under damaged infrastructure, such as limited energy resources and limited transport connectivity, working in coalition with multiple stakeholders (shown in Figure 9.6) involved in the relief activities, governmental interventions, and the final beneficiaries. From this, it may be well understood that HSCM operates in a more complex and challenging environment (Behl & Dutta, 2018). Furthermore, it is important that HSCM activities meet the triple bottom line (TBL) concept which is related to sustainability, i.e., addressing economic, environmental, and social concerns.

Actors in Humanitarian Logistics

Note. From Paciarotti, et al., 2021, p. 556. CC BY 4.0.. [Image description].

These humanitarian actors have distinct characteristics. They could have different geographical coverage. Furthermore, these actors can also be broadly different in nature, size, approach, mission, specialization, rules and regulations and scope of operations. Moreover, a humanitarian system is composed of a number of individualistic actors with self-sufficient perspectives which have a potential to become competitors (Maon, Lindgreen & Vanhamme, 2009). The presence of such a high number of differentiated and individualistic stakeholders raises the issue of better coordination of the relief chains and highlights the need for standards able to provide a shared language and shared understanding of procedures and processes.

The need for coordination will grow in the coming years also as a consequence of the increasing attention to localization in the humanitarian sector since the 2016 Global Humanitarian Summit (WHS, 2016). Localizing humanitarian response is “a process of recognizing, respecting and strengthening the leadership by local authorities and the capacity of local civil society in humanitarian action, in order to better address the needs of affected populations and to prepare national actors for future humanitarian responses.” (OECD, 2017). In practical terms this implies a greater and greater involvement of a plethora of different actors such as national authorities in aid recipient countries, national Societies of the Red Cross /Crescent, national/subnational/local non-governmental organizations (NGOs)/civil society organizations (CSOs), local and national private sector organizations (OECD, 2017). The resulting increasing complexity and necessity to cooperate adopting a shared “language” increasingly emphasizes the importance of widespread and shared standards. Usage of standardized processes, procedures, common templates, etc. increases interoperability between organizations, allowing coordination of the efforts between international and local partners.

The importance of coordination of humanitarian actors strongly emerged after the response to the Rwanda humanitarian crisis that began in 1994. In 1996, the problems and inefficiencies faced during this crisis determined the decision to launch the Sphere project, with the first set of minimum standards published and applied in 1998 (O’Donnell, Bacos & Bennish, 2002). In January 2000, the Sphere project published the first handbook identifying a set of a minimum standard in key lifesaving sectors to be achieved by emergency relief programs in order to improve the quality and accountability of NGOs for their actions in humanitarian responses.

Minimum standards are set in four key response sectors:

(1) water supply;

(2) sanitation and hygiene promotion (WASH);

(3) food security and nutrition;

(4) shelter, settlement and health.

In the following years, other standards have been developed adopting a similar approach, that is, via inclusive consultation processes with a wide group of practitioners. Currently, the Sphere, in coalition with other six standards initiatives:

(1) minimum standards for child protection in humanitarian action,

(2) livestock emergency guidelines and standards,

(3) minimum economic recovery standards,

(4) minimum standards for education,

(5) minimum standard for market analysis and

(6) humanitarian inclusion standards for older people and people with disabilities, constitutes the humanitarian standards partnership.

Despite that many areas of humanitarian operations are covered by this group of approved and widespread initiatives, the humanitarian logistics and supply chain are not yet deeply involved in this standardization process.

Syria Humanitarian Response

Syria represents one of the most complex Humanitarian Crisis in the world. With a total population of 21.7 million, 14.5 million people in Syria need humanitarian assistance. Out of which 11.8 million are already targeted by OHCA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (summarized from Humanitarian Insight, 2022).

Syria Crisis

Note. Syria Crisis From Freedom House, 2014. CC BY 2.0. Cropped.

Note. Syria Crisis From Freedom House, 2014. CC BY 2.0. Cropped.

The strategic objectives of Syria Humanitarian Response Plan 2022 -2023 are:

- Provide life-saving and life-sustaining humanitarian assistance to the most vulnerable people with an emphasis on those in areas with high severity of needs.

- Enhance the prevention and mitigation of protection risks and respond to protection needs through supporting the protective environment in Syria, by promoting international law, International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and though quality, principled assistance.

- Increase the resilience of affected communities by improving access to livelihood opportunities and basic services, especially among the most vulnerable households and communities.

There are 12 sectors in which help is provided to Syrian people under this plan:

- Coordination and Common Services

- Camp Coordination and Camp Management

- Protection

- Early Recovery and Livelihoods

- Education

- Food Security and Agriculture

- Health

- Nutrition

- Shelter and Non-Food Items

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

- Logistics

- Emergency Telecommunications

To learn more about what has been done in these sectors as Humanitarian Response, please visit Syria Humanitarian Response Plan 2022 – 2023.

Sustainable Humanitarian Supply Chain Management and Response to COVID-19

It is important that Humanitarian SCM activities meet the triple bottom line (TBL) concept, i.e., addressing economic, environmental, and social concerns. The TBL concept is aligned with the sustainability. Hence, it is necessary to carry out sustainable HSCM (SHSCM) activities. The organizations involved in relief activities are predominantly classified under three sections, namely bodies working under the United Nations (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland), international organizations (International Committee of Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland), and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (Doctors Without Borders, Geneva, Switzerland).

Disaster management is a set of operational activities and administrative decisions related to various disasters at all levels (Lu, Gao & Zhao, 2020). HSCM plays an integral role in disaster management. HSCM needs to be sustainable economically, environmentally, and socially; only then will HSCM meet the intended purpose of delivering medical essentials on time. Hence, SHSCM is critical in disaster management. Furthermore, SHSCM helps in meeting several sustainable development goals (SDGs), such as SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing) and SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals). SDGs are a set of goals proposed by the UN for the prosperity of people and the planet by the inclusive actions of global nations.

Did You Know? Challenges Faced by SHSCM

The role of SHSCM in COVID-19 is completely different and remains challenging compared to other more common disasters such as earthquakes, droughts, or floods. As a result, the organizations involved in SHSCM have no earlier experience (Lu, Gao & Zhao, 2020). Earlier studies have identified and discussed various challenges in SHSCM during a disaster situation. For instance, the study by Sabri et al. (2019) indicated a lack of coordination among the agencies involved in the relief activities as the fundamental challenge in SHSCM. This challenge results in a lack of communication, poor technological infrastructure, lack of administrative personnel, lack of clear policies, ineffective distributing relief material, and stagnation of relief activities (Vega, 2018).

Difficulty in fundraising is another challenge. With limited funds, only interim solutions are possible. For longer-term solutions, sufficient funds must be raised. Ozdemir et al. (2020) investigated the blockchain’s efficiency in minimizing SHSCM challenges and embarked on introducing new technologies. Another study by Dubey et al. (2019) on the role of big data in organizational assistance revealed that the usage of big data paved the way for swift trust and collaborative performance. A similar study on the adoption of big data by Prasad et al. (2018) emphasized raising awareness among the government and NGOs about how the latest technology mutually benefits each party in SHSCM.

Adopting the latest cutting-edge technology greatly helps the functions of SHSCM activities, but such adoption by emerging countries remains a challenge (Queiroz, Wamba, De Bourmont & Telles, 2020). With limited technological advancement, limited capital support, and limited awareness of technological advancement, developing countries cannot be expected to competently address SHSCM challenges without the intervention of reliable technologies.

Video: Supply Chain in the Humanitarian Context (8:04)

Let’s watch this video to know more about Supply Chain in Humanitarian Context.

Media 9.4. Supply Chain in the Humanitarian Context [Video]. HELP Logistics.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered above. You can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Check Your Understanding: Humanitarian Logistics

Media Attributions and References

Freedom House. (2014, February 6). [Syria Crisis] [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/syriafreedom/12340805415. CC BY 2.0.

HELP Logistics. (n.d.). Supply Chain in the humanitarian context [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/CKNeGGmNuCE.

Paciarotti, C., Piotrowicz, W.D. & Fenton, G. (2021). Humanitarian logistics and supply chain standards. Literature review and view from practice. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 11(3), 550-573. 10.1108/JHLSCM-11-2020-0101. CC BY 4.0.

participants

Some actors act at regional and local levels, others operate at national and some at a global level.