7.2 Value Chain Vulnerability and Current Challenges

Learning Objective

1. Explain the concept of value chain vulnerability by reviewing current challenges.

What is vulnerability? According to the Cambridge University Press (2022),

“Vulnerability is the quality of being vulnerable (able to be easily hurt, influenced, or attacked), or something that is vulnerable” (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Risks have always existed everywhere; however, globalization has increased the risk significantly internally and externally. Challenges within the global value chain could be lack of visibility within companies, chaos, inaccurate research or forecast, human mistakes, mother nature, political situation and so forth. The global value chain is a complex model with simultaneous flow of information and products . The right quantity of products must be effectively delivered to the right place and the right customer. Globalization has made the global value chain model more sophisticated and more vulnerable for all parties, with many interruptions and disruptions on the supply chain network. Nataliya Smorodinskaya, Daniel Katukov & Viacheslav Malygin (2021) presented a typical global value chain organizational model that can help you understand various value chain activities, which each of them can be at risk and have challenges.

Consider This: Global Value Chain Vulnerability

The following material is adapted from Global Value Chains in the Age of Uncertainty: Advantages, Vulnerabilities, and Ways for Enhancing Resilience by Smorodinskaya, Katukov & Malygin (2021) under Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0.

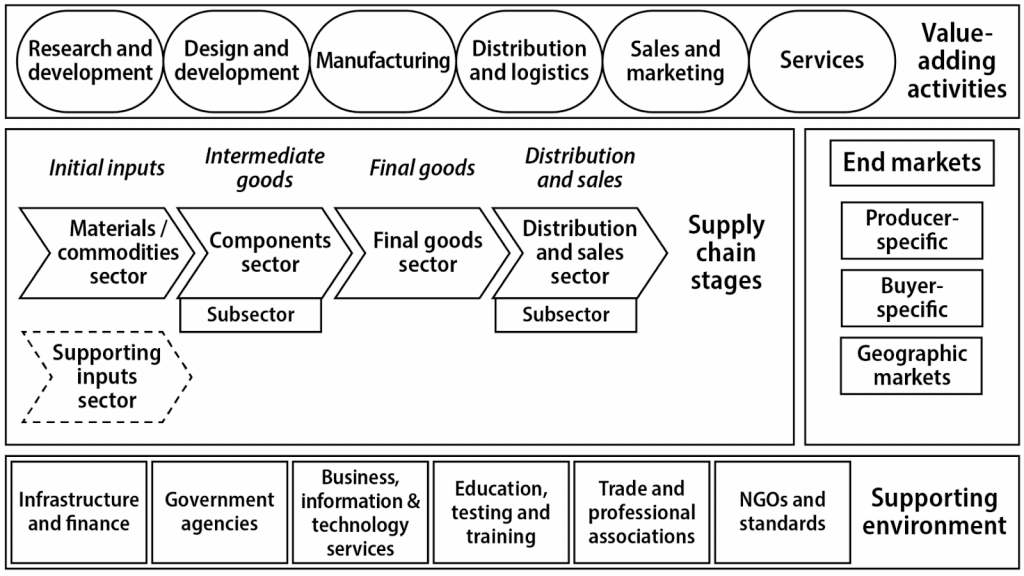

The concept of Global Value Chain relies on the value chain organizational model used for mapping particular firms, activities, and geographic locations involved in the co-creation of a final product, be it a physical good, a service or an enabling technology. This model is multi-structural, containing four key elements.

Figure 7.1

A typical Global Value Chain organizational model (industry-neutral)

Note. From Smorodinskaya, Katukov & Malygin, 2021. CC BY-4.0

They are:

- six main value-adding activities representing basic operational functions that Global Value Chains firms are engaged in to bring a product from an idea to the end use.

- four main supply chain stages (often termed in literature as ‘supply chains’ or ‘global supply chains’) illustrating the input–output structure of a product or the downstream flow of inter-firm interactions for its creation. Each stage represents supplier firms from a certain sector that can be further disaggregated into subsectors or intermediates delivered by second- or third-tier suppliers.

- end markets for final goods (basically, an extension of the supply chain), classified into several categories within a given industry, such as producer specific markets (e.g., for consumer electronics or automotive electronics in the electronics chains), buyer-specific markets (e.g., for retail consumers or industrial buyers in the apparel industry chains), and geographic markets.

- supporting environment uniting multiple local or global actors who do not directly produce and trade products but provide various supporting and regulative facilities enabling the chain’s smooth functioning (from utility providers and financial institutions to governments and international organisations)

For 30 years of evolution, the distributed production system has fundamentally enhanced functional interdependences among suppliers, their industry domains and their countries of origin, thus making the world economy much more interconnected through transnational flows of trade, foreign direct investment [FDI] and labour force. This interconnectedness not only brings mutual benefits but also risks to Value Chain Partners.

In economic and business literature, uncertainty is viewed as the probability of risk occurrence, when unexpected events cause certain kinds of damage to systems’ economic performance, with the scale of this damage being neither predicted nor insured against. Indeed, participation in Global Value Chain’s [GVC] allow companies and economies to co-create increasingly complex products that they would never manufacture on their own. But at the same time, the involvement in value-added production and trade puts interdependent Global Value Chain partners at risk of rolling disruptions in their performance in case of a sudden idiosyncratic shock happening at the level of a certain supplier firm (Smorodinskaya, Katukov & Malygin, 2021).

GVCs Under the Pandemic Shock

Since the start of the digital age, GVCs and their supplier ecosystems have been facing increasingly frequent and severe systemic shocks of various origins, causing supply disruptions and imposing damage on international business and national economies. So, the propagation of shocks through supply chains and its macroeconomic implications have been widely studied even before the COVID-19 pandemic, both in economic and management literature, both theoretically and empirically. According to McKinsey Global Institute, over the past decade, at least one-month-long disruptions in supplier networks occurred on average every 3.7 years, with one major disruption capable to stop production in a GVC for 100 days, thus depriving firms in a number of industries of annual revenues. In the year of 2019 alone, the supply disruptions caused only by natural disasters had imposed damage on the world economy up to USD 40 billion. However, the 2020 pandemic crisis has brought the worst shock to the distributed production system for its entire 30-years evolvement. The crisis has demonstrated that increased interconnectedness of economies as GVCs’ partners can put them at enormous destabilizing risks in case of a sudden fall in deliveries from just a single country, particularly from China. It has become clear that with all its advantages the modern system of production and trade is yet not tailored to safely meet powerful unpredictable shocks and should be seen fundamentally vulnerable to impacts of rising uncertainty. Among the biggest disruption risks that had fully realized at the start of the crisis was a combination of two factors — the involvement of GVCs’ country partners in the just-in-time delivery practices that had critically increased their interdependences and the revealed dependence of a significant share of these countries on intermediary imports from China, that had been steadily growing through over the past decade.

(Smorodinskaya et al., 2021) CC-BY-4.0

This is an excellent example of a current challenge that our world and global value chain have now faced and are dealing with it.

Check Your Understanding

Explain the concept of value chain vulnerability by reviewing current challenges.

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered above. You can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Interactive activity unavailable in this format

Text-based alternative to interactive activity available in Chapter 7.6.

Overall Activity Feedback

Globalization has made the global value chain model more sophisticated and more vulnerable for all parties, with many interruptions and disruptions on the supply chain network. The global value chain is a complex model with simultaneous flow of information and products . Also, it is essential to know activities of the concept of Global Value Chain which relies on the value chain organizational model. The model used for mapping particular firms, activities, and geographic locations involved in the co-creation of a final product, be it a physical good, a service or an enabling technology. This model is multi-structural, containing four key elements.

Media Attributions and References

Smorodinskaya, N., Katukov, D., & Malygin, V. (2021). Global value chains in the age of uncertainty: advantages, vulnerabilities, and ways for enhancing resilience. Baltic Region (13), 78-107. https://journals.kantiana.ru/eng/baltic_region/4953/31214/