5.3: Proofreading for Punctuation

Learning Objectives

1. Identify and correct punctuation errors involving commas, apostrophes, colons and semicolons, parentheses and brackets, quotation marks, hyphens and dashes, question and exclamation marks, and periods.

1. Identify and correct punctuation errors involving commas, apostrophes, colons and semicolons, parentheses and brackets, quotation marks, hyphens and dashes, question and exclamation marks, and periods.

2. ENL1813 Course Learning Requirement 1: Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

-

- Apply proper use of sentence structure, grammar, and punctuation (ENL1813 CLR B1.5)

- Use a systematic approach to edit, revise, and proofread (ENL1813 CLR R5.3)

- Spell, punctuate, and use vocabulary correctly (ENL1813A CLR 1.2)

- Edit and proofread documents to eliminate errors (ENL1813 CLRs H1.5, I1.5, M1.6, S1.6, T1.5)

- Revise documents to improve clarity, correctness, and coherence (ENL1813 CLRs G1.5, P1.4, R7.4)

As the little marks added between words, punctuation is like a system of traffic signs: it guides the reader towards the intended meaning of the words just as road signs guide drivers to their destination. They tell the reader when to go, when to pause, when to stop, when to go again, when to pay close attention, and when to turn (Truss, 2003, p. 7). They’re also crucial for avoiding accidents. A paragraph without punctuation—no periods, commas, apostrophes, etc.—quickly spins out into utter nonsense and kills the reader’s understanding of the writer’s meaning.

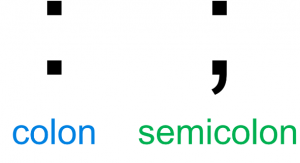

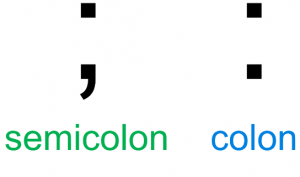

Punctuation that’s merely missing or unnecessary here and there can confuse a reader and even lead to expensive lawsuits if they plague contentious documents like contracts. To anyone who knows how to use them, seeing punctuation mistakes in someone else’s writing makes that other person look sloppy and amateurish. Punctuation errors by adult native English speakers look especially bad because they reflect poorly on their education and attention to detail, especially if they’re habitual mistakes. The critical reader looks down on anyone who hasn’t figured out how to use their own language in their 20+ years of immersion in it. Not knowing the difference between a colon and semicolon, for instance, is like not knowing the difference between a cucumber and a zucchini; sure they look alike from a distance, but they’re completely different species and serve different culinary functions. If you don’t know these differences by the time you’re an adult, however, it doesn’t take much to learn.

In this section, we focus on how to spot and correct common punctuation errors, starting with commas because most problems with people’s writing in general are related to missing and misused commas. The goal is to help you avoid making mistakes that can potentially embarrass you in the eyes of people who should be taking you seriously.

Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

- 5.3.1: Commas ( , )

- 5.3.2: Apostrophes ( ’ )

- 5.3.3: Colons ( : )

- 5.3.4: Semicolons ( ; )

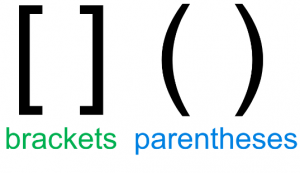

- 5.3.5: Parentheses ( )

- 5.3.6: Brackets [ ]

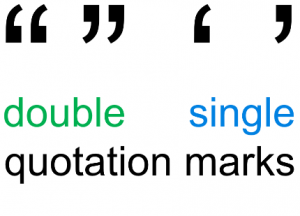

- 5.3.7: Quotation Marks ( “ ” )

- 5.3.8: Hyphens ( – )

- 5.3.9: Long Dashes ( — )

- 5.3.10: Question Marks ( ? )

- 5.3.11: Exclamation Marks ( ! )

- 5.3.12: Periods ( . )

5.3.1: Commas

Most punctuation problems are comma-related because of the important role commas play in providing readers with guidance on how a sentence is organized and is to be read to understand the writer’s intended meaning. As we saw in §4.3.2, commas signal to the reader where one clause ends and another begins in compound and complex sentences, but they serve several other roles as well. We use commas in four general ways, each with several variations and special cases. To these we can add rules about where not to add commas, since many writers confuse their readers by putting commas where they shouldn’t go. Most style guides advocate for using as few commas as possible, though you certainly must use them wherever needed to avoid ambiguities that lead readers astray. Closely follow the sixteen rules below to guide your reader towards your intended meaning and avoid confusing them with comma misplacement.

Quick Rules: Commas

Click on the rules below to see further explanations, examples, advice on what to look for when proofreading, and demonstrations of how to correct common comma errors associated with each one.

| Comma Rule 1.1 | Put a comma before coordinating conjunctions in compound sentences. The installers came to do their work at 8am, and the regulators came to inspect the installation by the end of the day. |

|---|---|

| Comma Rule 1.2 | Don’t put a comma between independent clauses in a compound sentence if not followed by a coordinating conjunction. Our main concern is patient safety; we don’t want any therapeutic intervention to cause harm. (semicolon rather than a comma after “safety”) |

| Comma Rule 2.1 | Put a comma after introductory subordinate clauses, phrases, or words preceding main clauses. If we can’t secure investor funding and launch the site by April, the clients will likely go elsewhere. |

| Comma Rule 2.2 | Don’t put a comma after main clauses followed by subordinate clauses or phrases unless the latter strikes a contrast with the former. They’re paying us a visit because they haven’t seen us in a while. (no comma before “because”) |

| Comma Rule 3.1 | Put commas around parenthetical words, phrases, or clauses. See my portfolio, which includes my best work, on ArtStation. |

| Comma Rule 3.2 | Put a comma before contrasting coordinate elements, end-of-sentence shifts, and omitted repetitions. He said, “go to Customer Service, not the checkout,” didn’t he? |

| Comma Rule 3.3 | Put a comma before sentence-ending free-modifier phrases that describe elements at the beginning or middle of sentences. We are putting in long hours on the report, writing frantically. |

| Comma Rule 3.4 | Put commas around higher levels of organization in dates, places, addresses, names, and numbers. Send your ticket to Gina Kew, RN, in Ottawa, Ontario, by Tuesday, October 9, 2018, for your chance to win the $5,000,000 prize. |

| Comma Rule 3.5 | Put a comma between a signal phrase and a quotation. The reporter replied, “Yes, this is strictly off the record.” |

| Comma Rule 3.6 | Don’t put commas around restrictive relative clauses (before that). The purchased item that we agreed to return is now completely lost. (no comma before “that” and after “return”) |

| Comma Rule 3.7 | Don’t put commas between subjects and their predicates. The just reward for the difficult and dangerous job that Kyle performed for his clientele was the knowledge that they were safe. (no comma before “was”) |

| Comma Rule 4.1 | Put commas between each item in a series, including the last two items. You must be kind, conscientious, and caring in this line of work. |

| Comma Rule 4.2 | Put commas between two or more coordinate adjectives. It was a cool, crisp, bright autumn morning. |

| Comma Rule 4.3 | Don’t put a comma after the final coordinate adjective. The team devised a daring, ambitious plan. (no comma after “ambitious”) |

| Comma Rule 4.4 | Don’t put a comma between non-coordinate adjectives. David played his Candy Apple Red ’57 reissue Fender Stratocaster electric guitar like he was flying a Saturn V rocket to the moon. (no comma between the non-coordinate adjectives throughout) |

| Comma Rule 4.5 | Don’t put commas between two coordinate nouns or verbs. Tesla and Edison invented and patented a complete circuit of electricity distribution systems and consumption devices. (no commas before any “and” here) |

Extended Explanations

Comma Rule 1.1: Put a comma before coordinating conjunctions in compound sentences.

Put a comma before the coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, so; Darling, 2014a) that joins two independent clauses in a compound sentence. A compound sentence contains two or more clauses that can stand on their own as sentences (see Table 4.3.2b for more on compounds sentences) with a different subject in each clause.

Correct:

We were having the time of our lives, and our lucky streak was far from over.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “and” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “We” and another beginning with the subject “our lucky streak.”

Correct:

The first round of layoffs was welcomed by all, but the second devastated morale.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “but” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “The first round” and another beginning with the subject “the second.”

Correct:

The management blamed external factors, yet none of the company’s blunders would have happened under good leadership.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “yet” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “The management” and another beginning with the subject “none.”

Correct:

You can take advantage of this golden opportunity, or a thousand other investors will take advantage of it instead as soon as they know about it.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “or” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “You” and another beginning with the subject “a thousand.”

Correct:

He didn’t see the necessity of lean principles, nor would they have made sense in a business model based on inefficiency.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “nor” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “He” and another beginning with the subject “they.”

Correct:

Market forces left them behind, for the law of supply and demand isn’t necessarily a force for social justice.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “for” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “Market forces” and another beginning with the subject “the law.”

Correct:

The competition started to heat up, so we did everything we could to protect our assets.

Why it’s correct: A comma precedes the coordinating conjunction “so” joining the independent clause beginning with the subject “The competition” and another beginning with the subject “we.”

Exception:

If the two independent clauses are short (five words or fewer), the comma may be unnecessary.

Correct:

You bring the wine and we’ll make dinner.

Why it’s correct: A comma is unnecessary before the coordinating conjunction “and” joining the two short, four-word independent clauses beginning with the subjects “You” and “we.”

How This Helps the Reader

The comma tells the reader to pause a little after one independent clause ends and before the coordinating conjunction signals that another (with a new subject) is joining it to make a compound sentence. In each of the examples sentences above, the independent clause on either side of the comma-conjunction combination could stand on its own as a sentence (see §4.3.1–§4.3.2 for more on sentence structure and independent clauses). In the first example above, for instance, we could replace the comma and conjunction with a period, then capitalize the o in “our,” and both would be grammatically correct sentences. We combine them with a comma and the conjunction and, however, to clarify the relationship between the two ideas. The comma signals that these are coordinated clauses rather than noun or verb phrases.

If the subject were the same in both clauses, however, both the comma and subject of the second clause would be unnecessary. In that case, the sentence would just be a one-subject clause with a compound predicate—that is, two coordinated verbs (see Comma Rule 4.4 below). Consider the following examples:

Correct:

We were having the time of our lives and would continue to enjoy that lucky streak.

Why it’s correct: The subject “we” is the same in the independent clauses “We were having the time of our lives” and “we would continue to enjoy that lucky streak,” so the comma and second “we” are omitted to make a compound predicate joining the verbs “were having” and “would continue” with the coordinating conjunction “and.”

Correct:

They won the battle but lost the war.

Why it’s correct: The subject “They” is the same in the independent clauses “They won the battle” and “they lost the war,” so the comma and second “they” are omitted to make compound predicate joining the verbs “won” and “lost” with the coordinating conjunction “but.”

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for run-on sentences (see §5.2.1.2 above), which are sentences that omit a comma before the coordinating conjunction joining two independent clauses. Keep an eye out for the seven coordinating conjunctions for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so (see Table 4.3.2a and use the mnemonic acronym fanboys to remember them). Simply add a comma before the conjunction if the independent clause on either side of the conjunction could stand on its own as a sentence because it has a subject and predicate (see §4.3.1 for more on sentence structure).

Incorrect:

We were losing money with each acquisition but our long-term plan was total market dominance.

Incorrect:

We were losing money with each acquisition but, our long-term plan was total market dominance.

The fix:

We were losing money with each acquisition, but our long-term plan was total market dominance.

In the example above, the coordinating conjunction “but” joins the two independent clauses beginning with the subjects “We” and “Our long-term plan.” Omitting the comma in the first example makes the sentence a run-on. Misplacing the comma after the conjunction in the second miscues the reader to pause after, rather than before, the conjunction. The easy fix is just to add the comma or move it so it goes before the conjunction.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 1.2: Don’t put a comma between independent clauses in a compound sentence if not followed by a coordinating conjunction.

Don’t put a comma between two independent clauses if it’s not followed by a coordinating conjunction because this is a comma splice sentence error (see §5.2.1.1 above). We have two distinct ways of forming a compound sentence (see §4.3.2 above) and a comma splice confuses the two. One way of making a compound sentence is to join independent clauses by placing a comma and one of the seven “fanboys” coordinating conjunctions between them (see Table 4.3.2a for the coordinating conjunctions). Simply omitting the coordinating conjunction after the comma makes a comma splice. The other way of making a compound sentence is to end the first clause with a semicolon when it doesn’t make sense to use any of the coordinating conjunctions to establish a certain relationship between the clauses (see Table §4.3.2b on sentence varieties for more on compound sentences and Semicolon Rule 1 below). Using a comma instead of a semicolon in such compound sentences makes a comma splice.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for commas separating two independent clauses (clauses that can stand on their own as sentences because they each have a subject and predicate) without any of the seven coordinating conjunctions (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, or so) following the comma.

Incorrect:

The first proposal was from the Davidson group, the second came from a company we hadn’t seen before.

The fix:

The first proposal was from the Davidson group; the second came from a company we hadn’t seen before.

The fix:

The first proposal was from the Davidson group; but the second came from a company we hadn’t seen before.

The fix:

Though the first proposal was from the Davidson group, the second came from a company we hadn’t seen before.

In the incorrect example above, the comma separates two independent clauses that can stand on their own as sentences if you replaced the comma with a period and capitalized the t in “the second.” You have three options for fixing the comma splice corresponding to the three examples above:

- Replace the comma with a semicolon to make a compound sentence.

- Add a coordinating conjunction, such as but, to make a compound sentence that clarifies the relationship between the clauses.

- Add a subordinating conjunction, such as Though, at the beginning of the first clause to make it a dependent (a.k.a. a subordinate) clause. This makes the sentence a complex one (see §4.3.2 above for more on subordinating conjunctions and complex sentences).

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 2.1: Put a comma after introductory subordinate clauses, phrases, or words preceding main clauses.

Put a comma before the main clause (a.k.a. independent clause) when it is preceded by an introductory word, phrase (e.g., a prepositional or participial phrase), or subordinate clause (a.k.a. dependent clause) in a complex sentence.

Correct:

If we follow our project plan’s critical path down to the minute, we will finish on time and on budget.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the subordinate clause beginning with the subordinating conjunction “If” from the main clause (beginning with the subject “we”) that follows it.

Correct:

When my ship comes in, I’ll be repaying every favour anyone ever did for me.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “When,” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “I.”

Correct:

To make ourselves better understood, we’ve left post-it notes all around the room.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory infinitive phrase, beginning with the infinitive verb “To make,” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “we.”

Correct:

After the flood, the Poulins took out some expensive disaster insurance.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory prepositional phrase, beginning with the preposition “after,” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “the Poulins.”

Correct:

Greeting me at the door, she said that I was a half hour early and would have to wait to see the director.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory participial phrase, beginning with the present participle (Simmons, 2001a) “Greeting,” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “she.”

Correct:

The downturn of 2008 now forgotten, the investors threw other people’s money around like it was 2007 again.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory absolute phrase, ending with the past participle (Simmons, 2001a) “forgotten,” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “the investors.”

Correct:

Delighted, she accepted their offer even with the conditions.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the single-word introductory past-participle appositive (Simmons, 2001b) “Delighted” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “she.”

Correct:

Therefore, you are encouraged to submit your timesheet the Friday before payday.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory conjunctive adverb (Simmons, 2007b) “Therefore” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “you.”

Correct:

However, there’s not much we can do if the patient refuses our help.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the introductory conjunctive adverb “However” from the main clause that follows it, beginning with the subject “you.”

Correct:

Yes, please go ahead and submit your payment.

Why it’s correct: The comma separates the single-word introductory interjection “Yes” from the main clause imperative clause that follows it, the core of which is the verb “go.”

Correct:

Hello, Claude:

Why it’s correct: The comma marks the pause between the greeting word and name address in a respectful, semiformal salutation opening email.

Exception: The comma is unnecessary if the introductory dependent clause or prepositional phrase is short (fewer than four words) and its omission doesn’t cause confusion.

Correct:

At this point we’re not accepting any applications.

Why it’s correct: Omitting the comma after the short, three-word prepositional phrase doesn’t cause confusion.

How This Helps the Reader

The comma tells the reader to pause a little prior to the main clause as if to say, “Okay, here’s where the sentence really begins with the main-clause subject and predicate.” The main clause is the main point, whereas the subordinate clause that precedes it is relatively minor, providing context.

Recall from the lesson on sentence varieties (§4.3.2) that a complex sentence is one where a subordinating conjunction (Darling, 2014a) begins an independent or subordinate clause, which cannot stand on its own as a sentence. A subordinate clause (a.k.a. dependent clause) becomes part of a proper sentence only when it joins a main (a.k.a. independent) clause. When that subordinate clause precedes the main clause, a comma separates them. The same is true when that main clause is preceded by a phrase (e.g., prepositional, infinitive, participial, gerund, etc.; Darling, 2014b) or even just a word such as an appositive participle (as in the “Delighted” example above) or conjunctive adverb (Darling, 2014c), as in the “Therefore” example above.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for words, phrases, or clauses preceding the main clause without a comma separating them. For this, you must know how to spot the main clause when it comes later in the sentence; in other words, you need to be able to spot the main grammatical subject (the doer of the action) and predicate (the action itself; review §4.3.1’s introduction to sentence structure). If the main subject is preceded by words, phrases, or clauses but not a comma, then you need to add one before the main clause.

Incorrect:

Because first impressions are lasting ones you must always come out swinging at the beginning of your presentation.

The fix:

Because first impressions are lasting ones, you must always come out swinging at the beginning of your presentation.

In the example above, “you” is the main grammatical subject that begins the main clause, whose main verb is “come.” The subordinate clause begins with the subordinating conjunction “Because” and ends at “ones,” so the comma must follow “ones” to separate it from the beginning of the main clause.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 2.2: Don’t put a comma after main clauses followed by subordinate clauses or phrases unless the latter strikes a contrast with the former.

Don’t put a comma after a main clause (a.k.a. independent clause) if it is followed by a subordinate (a.k.a. dependent) clause or phrase in a complex sentence. If the subordinate clause begins with a contrasting subordinating conjunction such as “although,” a comma must separate the two clauses.

Correct:

You can’t apply for permits from the city because you haven’t even secured funding yet.

Why it’s correct: A comma is unnecessary because the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “because,” follows the main clause rather than precedes it, so you can read it without a pause.

Correct:

We will finish on time and on budget if we follow the critical path of our plan to the minute.

Why it’s correct: A comma is unnecessary because the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “if,” follows the main clause rather than precedes it, so you can read it without a pause.

Correct:

I’ll be repaying every favour anyone ever did for me when my ship comes in.

Why it’s correct: A comma is unnecessary because the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “when,” follows the main clause rather than precedes it, so you can read it without a pause.

Correct:

The Poulins took out some expensive disaster insurance after the flood.

Why it’s correct: A comma is unnecessary because the prepositional phrase, beginning with the preposition “after,” follows the main clause rather than precedes it, so you can read it without a pause.

Correct:

We’re not accepting any applications at this time, though we might make an exception for a truly remarkable applicant.

Why it’s correct: A comma is necessary because the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “though,” strikes a contrast with the main clause that precedes it, making a pause appropriate.

Correct:

We could easily hire a new full-time assistant in the fourth quarter, unless our profit margin drops below 5% in the third.

Why it’s correct: A comma is necessary because the subordinate clause, beginning with the subordinating conjunction “unless,” strikes a contrast with the main clause that precedes it, making a pause appropriate.

How This Helps the Reader

The absence of the comma tells the reader to keep reading smoothly without pause between the main and subordinate clauses. In the case of the contrasting subordinate clause, however, the comma signals a pause as if to say that the subordinate clause is a kind of afterthought or qualification added to the main clause.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for commas unnecessarily added before subordinating conjunctions (see Table 4.3.2a for a list of subordinating conjunctions) in complex sentences where the subordinate clause follows the main clause and doesn’t strike a contrast with it.

Incorrect:

The technician is switching to plan B, because the manifold blew a gasket.

The fix:

The technician is switching to plan B because the manifold blew a gasket.

Incorrect:

The Goliath Games label was founded in 2003, to create the most innovative and progressive interactive entertainment.

The fix:

The Goliath Games label was founded in 2003 to create the most innovative and progressive interactive entertainment.

In the examples above, the comma is simply unnecessary and should be deleted. It would be necessary, however, if the first sentence began with the subordinate clause beginning with “Because . . . ” or after the infinitive phrase if the second sentence began with “To create . . . .” In those cases, the comma would follow “gasket” and “2003” respectively and you would change the first letter in the main clauses to lowercase.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.1: Put commas around parenthetical words, phrases, or clauses.

Put commas before and after parenthetical or non-essential words, phrases, or clauses that would leave the sentence grammatically correct if you omitted them. Placed in the middle of a sentence between the subject and predicate or at the end of the sentence, however, those elements lend further detail to the words or phrases that come just before them. Commas in this way function as a lighter form of parentheses (see §5.3.5 below).

Correct:

The promotion went to Mr. Speck, who neither wanted nor deserved it, to make it look like something was being done about the glass ceiling.

Why it’s correct: Like parentheses, the commas mark off the relative clause beginning with the relative pronoun “who” in the middle of the sentence, lending more information on the word coming just before (“Mr. Speck”).

Correct:

Global Solutions went on a hiring spree, which was well-timed given the change in telecoms legislation that was about to come down.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks the switch to a restrictive relative clause beginning with the relative pronoun “which” after the main clause, lending more information to its final word, “hiring spree.” The restrictive relative clause is non-essential in the sense that the main clause still means the same thing if the restrictive clause were omitted.

Correct:

We’ll get back to you as soon as possible, needless to say.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks the switch to an interjection tacked onto the end of the sentence.

Correct:

The second customer, on the other hand, absolutely loved the new colour.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off a parenthetical prepositional phrase separating the subject from the predicate in the middle of the sentence.

Correct:

The time for expressing interest in the buy-out option, however, had long since passed.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the conjunctive adverb “however” interjected between the subject and the predicate in the middle of the sentence.

Correct:

We’ve heard that, in fact, the delegation won’t be coming after all.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off a parenthetical prepositional phrase interjected between the subject and the predicate in the middle of the sentence.

Correct:

Always treat the customer with respect, unless of course certain behaviours, such as belligerent drunkenness, compel you to take a firm stand against them.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off a parenthetical phrase offering an example interjected between the subject and the predicate in the middle of the dependent clause.

Correct:

The nicest thing about you, Josh, is that you get the best work out of your employees by only praising achievements rather than criticizing mistakes.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off a parenthetical appositive address clarifying who “you” is between the subject and the predicate in the middle of the sentence.

Correct:

I sent the application to Grace Garrison, the departmental secretary, last Tuesday.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off a parenthetical appositive noun phrase identifying the role of the person named.

Exceptions: When the appositive is so close to the noun it modifies that the sentence wouldn’t make sense without it, omit the commas. Also omit commas:

- Before such as when exemplifying non-parenthetically

- Around restrictive relative clauses (i.e., those beginning with that; see Comma Rule 3.6)

- If too many commas would clutter the sentence, in which case you would drop any comma that wouldn’t cause confusion if omitted

Correct:

Departmental secretary Grace Garrison received the application Tuesday.

Why it’s correct: You can omit commas around the appositive following “Departmental secretary” because “Departmental secretary received the application” wouldn’t make sense unless “The” preceded it.

Correct:

They offer competitive fringe benefits such as health and dental coverage, three weeks’ paid vacation per year, and sick leave.

Why it’s correct: A comma would be excessive before the “such as” phrase introducing the list of examples unless it appeared as a parenthetical aside in the middle of the sentence.

Correct:

We don’t have to go, and of course they don’t have to take us.

Why it’s correct: Adding commas around “of course,” though technically correct, would be excessive and look cluttered, so the parenthetical commas drop in priority to the comma separating compounded independent clauses.

How This Helps the Reader

As light alternatives to parentheses, these parenthetical commas tell the reader to pause a little when a non-essential (a.k.a. parenthetical) point is interjected or tacked on to explain the word or phrase preceding it. Common parenthetical phrases include:

| all things considered as a matter of fact as a result as a rule at the same time consequently for example furthermore |

however in addition incidentally in fact in my opinion in the first place in the meantime moreover |

needless to say nevertheless no doubt of course on the contrary on the other hand therefore under the circumstances |

Interestingly, this rule also helped the Atlantic Canada telephone company Bell Aliant cancel a contract with Rogers Communications over the use of telephone poles prior to Rogers’s intended five-year term, costing Rogers a million dollars and resulting in a bitter court battle in 2006. The dispute concerned the following sentence in the middle of the 14-page contract:

This agreement shall be effective from the date it is made and shall continue in force for a period of five (5) years from the date it is made, and thereafter for successive five (5) year terms, unless and until terminated by one year prior notice in writing by either party.

Without the comma after “terms,” you could read the contract as Rogers intended, which was to say that it could be terminated with a year’s notice any time after the first five years. By adding the second comma to make the “and thereafter” phrase parenthetical and therefore non-essential, however, Rogers in effect made the “unless . . .” clause apply to the first five-year term as well as to any subsequent term. That one misplaced comma thus gave Bell Aliant the right to cancel at any time.

Citing this parenthetical comma rule, the Canadian Radio-Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) ruled in favour of Bell Aliant at Rogers’s expense (Austen, 2006). The CRTC later reversed its ruling when Rogers invoked the less ambiguous French version of the contract to force Aliant to return to its contractual obligations. Still, Rogers ultimately paid heavily for un-recouped losses during the contract’s cancellation and in legal fees throughout the contract dispute, which dragged out till 2009 (Bowal & Layton, 2014). You can bet Rogers pays people to ensure its contracts are punctuated unambiguously now.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for words, phrases, or clauses that could be deleted from a sentence without making it grammatically incomplete. Add commas if none mark off the parenthetical word, phrase, or clause, or if the first is there but not the second (or vice versa) in the case of parenthetical elements ending a sentence.

Incorrect:

Emphasizing your spoken points with gesticulation which may sound like a dirty word can certainly help your audience understand them better.

The fix:

Emphasizing your spoken points with gesticulation, which may sound like a dirty word, can certainly help your audience understand them better.

Here, the non-essential parenthetical relative clause beginning with the non-restrictive relative pronoun which (see Table 4.4.2a, #7, for relative pronouns) and ending with “word,” could be deleted from the sentence and leave it grammatically complete. However, as an interjection, it clarifies the word that precedes it (“gesticulation”), and therefore has a place in the sentence, albeit one set apart from the rest.

Incorrect:

Let’s start cooking Grandpa!

The fix:

Let’s start cooking, Grandpa!

Here, the comma is crucial in signalling that Grandpa is being addressed. Without the comma, the sentence recommends preparing Grandpa to be cooked and presumably eaten, which is hopefully not the intended meaning.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.2: Put a comma before contrasting coordinate elements, end-of-sentence shifts, and omitted repetitions.

Put commas before end-of-sentence:

- Questions that seek confirmation of the main-clause point by asking the opposite

- Phrases that begin with not and state what the main-clause point seeks to correct

- Coordinate elements that contrast or further extend the main-clause point

Correct:

This presentation seems like it’s gone on for days, doesn’t it?

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off the question added to the end of the sentence to ask whether the opposite of the main-clause point is true as a way of seeking agreement with it.

Correct:

Please send the document to Accounts Receivable, not Payable.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off the contrasting element added to the end, abbreviating the clause “do not send the document to Accounts Payable,” which has the exact structure of the main clause, but shows only the words that differ from the main-clause wording rather than repeating most of it to make a compound sentence.

Correct:

The potential we envision for AI is that it will at best bring a world of convenience and leisure, at worst total annihilation.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off the clause that states the complementary contrast to the first statement by omitting the repeated relative clause root “it will . . . bring.”

Correct:

The president’s statement to the media seemed incoherent, even demented.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off the clause that extends the main clause statement assuming the same root structure.

How This Helps the Reader

The comma cues the reader to pause before the sentence shifts to contrasting elements, as well as to indicate that some phrasing from the first part of the sentence is being assumed rather than repeated in the second.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for run-on-like gaps where no punctuation separates the main clause from questions or contrasting phrases tacked on to the end of a sentence, and add the comma.

Incorrect:

This is a great time to be alive isn’t it?

The fix:

This is a great time to be alive, isn’t it?

Here, the main clause ends with “alive,” and the follow-up recasting of the statement as an interrogative sentence (“isn’t this the best time to be alive?”) abbreviated as “isn’t it?” forms a run-on without any punctuation separating it from the main clause. The comma added between the clauses represents the words that were omitted to avoid repetition.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.3: Put a comma before sentence-ending free-modifier phrases that describe elements at the beginning or middle of sentences.

Put commas before phrases that appear at the end of a sentence but modify (describe) actions or things at the sentence’s beginning or middle. As long as such phrases don’t cause confusion with their ambiguity, they are free to either follow the noun they modify or appear at the end.

Correct:

The MC desperately cued for applause, clapping aggressively.

Why it’s correct: The comma marks off the sentence-ending participial phrase starting with the present participle “clapping” describes the action “cued” in the middle of the sentence.

How This Helps the Reader

The comma signals to the reader that the phrase ending the sentence refers to something that came earlier in the sentence. Without a comma, the phrase would describe what came immediately before it.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for phrases (especially participial phrases—words ending -ing) at the end of sentences without commas preceding them but not making sense. If they indeed have commas preceding them but the participle could refer to more than one thing in the main clause, resolve the ambiguity by moving the phrase closer to the thing it modifies.

Incorrect:

The bellhop held out his hand for a gratuity smiling obsequiously.

The fix:

The bellhop held out his hand for a gratuity, smiling obsequiously.

Here, the omitted comma makes it seem like the gratuity is smiling obsequiously, which doesn’t make sense. Adding the comma before “smiling” makes it clear that the bellhop mentioned earlier in the sentence is the one smiling.

Incorrect:

The MC invited the plenary speaker to the stage, bowing graciously.

The fix:

Bowing graciously, the MC invited the plenary speaker to the stage.

The participial phrase is ambiguous when placed at the end of the sentence because it’s unclear whether the MC or plenary speaker is bowing graciously. Moving the participial phrase to the beginning so that it is in appositive relation to the noun it modifies clarifies the sentence to say that the MC is bowing.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.4: Put commas around higher levels of organization in dates, places, addresses, names, and numbers.

Put commas around the:

- Year when preceded by a month and date

- Date when preceded by a day of the week

- Larger geographical region (e.g., province, state, country, etc.) when preceded by smaller one (e.g., city or town) in a sentence or long address line

- Title or credential (e.g., ND, MD, PhD) following a name

- Groups of thousands in large numbers

Correct:

The release date of April 14, 2019, will be honoured if there are no delays.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the year as parenthetical in the three-part date to ensure that there is no ambiguity about which April 14 (2018? 2020?) is intended.

Correct:

We agreed to continue our meeting on Thursday, January 28, to cover the agenda items we didn’t get to on Monday.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the calendar date as parenthetical after the day of the week to ensure that there is no ambiguity about which Thursday is intended.

Correct:

Gord Downie was born in Amherstview, Ontario, to a traveling salesman father and stay-at-home mother.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the province as parenthetical after the smaller town to ensure that there is no ambiguity about which town is intended, assuming other towns in other provinces may share the same name.

Correct:

Bowie was born David Robert Jones in London, England, on 8 January 1947.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the country as parenthetical after the city within it to ensure that there is no ambiguity about which city is intended (i.e., not the one in Ontario, Canada).

Correct:

Send your inquiries to 1385 Woodroffe Avenue, Ottawa, ON K26 1V8.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the larger geographical region in which the street is situated.

Correct:

Please welcome Daria Rimini, RN, to the department.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the person’s credentials as non-essential to her name rather than initials in her name.

Correct:

Send your inquiries to Albert Irwin, Jr., at the email address below.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the generational tag following the name.

Correct:

You can always trust old George Wilson, Professor of English, to make a mountain of a molehill.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off the individual’s professional title following their name.

Correct:

The awards for damages ranged anywhere from a token $4,882 to a whopping $13,945,718.

Why it’s correct: The commas mark off every group of thousand (three digits) to help the reader quickly recognize the magnitude of the number without counting the number of digits.

Exceptions:

Don’t surround a year with commas if it follows only a month; use them only around years following a month and date. Also, drop the second comma if the larger geographical region is possessive in form.

Correct:

Recording began in November 2005 and continued to February 2006.

Why it’s correct: Commas are unnecessary in general two-part dates.

Correct:

The charm of London, Ontario’s street buskers almost rivals that of its UK namesake.

Why it’s correct: A comma following the possessive form of the larger geographical region would look even more awkward than this. Of course, the sentence could be reworded as “The street buskers’ charm in London, Ontario, almost . . . .”

How This Helps the Reader

The commas tell the reader to pause a little within a detailed series of time, geographical, or name designations when adding a higher order of organization just as commas were used as light alternatives to parentheses in Comma Rule 3.1.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for years added to three-part dates, larger geographical regions added after cities and towns, or credentials added after names with either no comma added on either side of that year, region, or credential, or added only before it but not after. Add both or the second comma. If the date only has the month and year, but a comma or two surrounds the date, delete commas.

Incorrect:

We can probably fit you in for the procedure on Tuesday December 12.

The fix:

We can probably fit you in for the procedure on Tuesday, December 12.

Here, the month and date follow the day of the week without a comma. Just add one between them.

Incorrect:

They moved the release date to March 14, 2020 to allow enough time for post-production.

The fix:

They moved the release date to March 14, 2020, to allow enough time for post-production.

Here, the year gets the first of its two parenthetical commas but not the second, so just add one after the year.

Incorrect:

The company was founded in July, 1978, to address an urgent need.

The fix:

The company was founded in July 1978 to address an urgent need.

The commas around the year are unnecessary because it’s only a two-part date. Just delete them.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.5: Put a comma between a signal phrase and a quotation.

Put commas between signal phrases and the quotations they introduce when the signal phrases end with a verb that gives rise to the quoted words or thoughts.

Correct:

The chair of the meeting shouted, “We cannot proceed unless we have order.”

Why it’s correct: A comma separates the signal phrase ending with a verb from the quotation it introduces.

Correct:

“Stay the course,” the supervisor advised, “and you shall soon find success.”

Why it’s correct: The parenthetical commas mark off the signal phrase interjected between quoted clauses.

Correct:

You could tell she was thinking, “Is this guy for real?”

Why it’s correct: A comma separates the signal phrase ending with a verb from the quotation it introduces even if the quotation is merely thought rather than said.

Exception:

A comma is unnecessary if the signal phrase ends with the restrictive relative pronoun that or the quotation is a phrase incorporated into the sentence rather than a sentence or clause on its own.

Correct:

The customer service rep said that “The offer expired on August 23, not the 24th” and they have a “no exceptions” policy due to the perishable nature of the product.

Why it’s correct: The signal phrase ends with the restrictive relative pronoun that, which a comma doesn’t follow but could replace, and “no exceptions is a phrase rather than a clause or sentence.

Correct:

The customer service representative confirmed “August 23, not the 24” was the expiration date.

Why it’s correct: No comma follows the signal phrase because the quotation is just a phrase excerpt rather than a clause or sentence.

How This Helps the Reader

The comma cues the reader to pause as it abbreviates the relative pronoun that, which makes the comma unnecessary if it’s included.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for missing commas around quotations and add them between the signal phrase ending with a verb and the quotation, or look for unnecessary commas that split a sentence unnaturally, such as going before or after the that that precedes a quotation if present), and delete them.

Incorrect:

The authorization said “Go for it.”

The fix:

The authorization said, “Go for it.”

Here, the signal phrase omits a comma between the main verb and the quotation, so adding one corrects the error.

Incorrect:

The current contract says clearly that, “overtime is time and a half.”

The fix:

The current contract says clearly that “overtime is time and a half.”

Here, a comma unnecessarily follows the relative pronoun that perhaps because the writer thought that a comma should always precede the quotation. You could either delete the comma or “that,” but not both.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.6: Don’t put commas around restrictive relative clauses (before that).

Don’t put a comma before a restrictive relative clause (e.g., beginning with the relative pronoun who or that) following a main clause.

Correct:

The stocks that we all thought were going to offer the best returns are doing the worst.

Why it’s correct: No commas surround the restrictive clause from “that” to “returns,” which is somewhat parenthetical in that the sentence could grammatically function without it (“The stocks are doing the worst”). However, this would be misleading because it implies that all the stocks are failing expectations, whereas the sentence focuses on only a subset. The vagueness resulting from omitting the restrictive clause proves that it is essential to the sentence’s clarity.

Correct:

The students who presented first set the bar high for those who followed.

Why it’s correct: No commas surround the restrictive clause from “who” to “first.” The clause is restrictive because it specifies a small group of students. Adding commas around the clause would make it non-restrictive (see Comma Rule 3.1 above) and would change the meaning of the sentence: it would mean that all the students presented first.

Correct:

She didn’t say that we couldn’t work together.

Why it’s correct: No comma precedes the restrictive clause beginning with “that.”

How This Helps the Reader

The absence of the comma tells the reader that the relative clause starting with the relative pronoun that or who is essential to the meaning of the sentence and should be read smoothly without pauses around it. For more on restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses, see Introduction and General Usage in Defining Clauses (Keck & Angeli, 2018) and Clauses (Darling, 2014d).

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for commas preceding that or who and determine whether the meaning of the sentence would be significantly changed if you deleted the restrictive relative clause. If it would be, delete the commas.

Incorrect:

You don’t have to cite common-knowledge facts, that every source you can find agrees on.

The fix:

You don’t have to cite common-knowledge facts that every source you can find agrees on.

Here, the restrictive relative clause beginning with that is essential to the meaning because it clarifies what kind of facts are common knowledge. It is not interchangeable with the non-restrictive relative clause beginning with which, which requires a comma before it because it is non-essential (see Comma Rule 3.1 above). In the UK, writers often use “which” instead of “that” even in non-restrictive relative clauses without the comma preceding them. In North America, however, we distinguish the relative clause types by using a comma and which for non-restrictive clauses and that without a comma for restrictive clauses.

Incorrect:

The students, who were caught plagiarizing, were each given a zero, whereas the rest did quite well.

The fix:

The students who were caught plagiarizing were each given a zero, whereas the rest did quite well.

Here, the commas in the incorrect sentence say that all students were caught plagiarizing. Deleting the commas to make “who were caught plagiarizing” a restrictive relative clause brings the sentence back to the intended meaning, which is that a subset of students were caught plagiarizing and the rest did well.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 3.7: Don’t put commas between subjects and their predicates.

Don’t put a comma between a clause’s subject (even if it’s a long one) and predicate (the main verb action) if there are no parenthetical elements between them.

Correct:

Participants who quit smoking because of the new treatment option were twice as likely to remain smoke-free as those who quit cold turkey.

Why it’s correct: No comma separates the subject “Participants who . . . option” from the predicate “were . . . turkey” even though the subject is quite long at ten words.

Exception:

Adding a pair of commas between the subject and predicate is acceptable when they are divided by an interjection. See the fourth and fifth correct examples illustrating Comma Rule 3.1).

How This Helps the Reader

The absence of the comma tells the reader to read smoothly across the subject and predicate because they are the integral parts of a unified clause even if the subject is long.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for commas that separate the subject from the predicate when there are no parenthetical words or phrases, or non-restrictive clauses, separating them. For this, you must know how to spot the main-clause subject and predicate (review §4.3.1 on sentence structure) and delete any stray commas that come between them.

Incorrect:

All the businesses that benefitted from the new regulatory environment following the passing of Bill 134, have given back to their community.

The fix:

All the business that benefitted from the new regulatory environment following the passing of Bill 134 have given back to their community.

The subject of the above sentence is a long one because, following the core noun “businesses,” it contains a restrictive relative clause beginning with that, which contains prepositional phrases (“from the new . . .” and “of Bill 134”) and a participial phrase (“following . . .”). None of these length-extending units change the fact that there is no legitimate parenthetical interjection requiring commas between the subject and the predicate that begins with “have given.” The easy fix is just to delete the comma.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 4.1: Put commas between each item in a series, including the last two items.

Put commas between each item in a series, including before the and or or that separates the second-to-last (a.k.a. penultimate) and last items, whether those items be words, phrases, or even clauses in a series.

Correct:

NASA sent the space shuttles Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour on 135 orbital missions from 1982 to 2011.

Why it’s correct: A comma follows each noun in a series up to the penultimate one before the and joining the last two.

Correct:

I gave them the option of either researching the content, preparing the PowerPoint, or doing the actual presentation.

Why it’s correct: A comma follows each participial phrase in a series up to the penultimate one before the or joining the last two.

Correct:

The presenters rehearsed before Week 5, during Reading Week, and again after Week 7.

Why it’s correct: A comma follows each prepositional phrase in a series up to the penultimate one before the and joining the last two.

Correct:

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards set the stage for other singer-guitarist power duos like Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, Freddie Mercury and Brian May, Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, Axl Rose and Slash, and Anthony Kiedis and John Frusciante.

Why it’s correct: A comma follows each compound noun phrase in a series up to the penultimate one before the and joining the last two pairs.

Correct:

I can’t stand comma splices, you have no patience for run-ons, and she won’t tolerate sentence fragments.

Why it’s correct: In a compound sentence containing three independent clauses, a comma follows each clause up to the penultimate one before the and joining the last two.

How This Helps the Reader

The serial commas help separate each item in the series, and the one that comes before the coordinating conjunction and that joins the last two items (a.k.a. the “Oxford comma”), helps resolve various ambiguities that may arise without it (see some below). The question of whether to use the Oxford comma has been a long-running debate. Some style guides, such as the Canadian Press, Associated Press, and even institutions like Algonquin College, recommend omitting it because they advocate for as few commas as possible. However, they say nothing about situations where omitting the Oxford comma creates unavoidable ambiguity—that is, two interpretations that mean two very different things. The anti-Oxford comma side even has an anthem in the Grammy-winning indie band Vampire Weekend’s 2008 debut-album single “Oxford Comma,” which opens with the lyric “Who gives a f**k about the Oxford comma?”.

However, grammarians, readers, and writers who care about clarity in writing, and even the plaintiffs awarded $5 million in a US civil suit (as well as the defendants paying the price) certainly care about the Oxford comma. The significant confusion and even conflict that results from its absence in clutch situations justifies its inclusion in all. For instance:

- In a 2017-2018 civil case that went nearly as far as the US Supreme Court, Oakhurst Dairy of Portland, Maine, was ordered to pay its delivery drivers $5 million due to the ambiguity caused by an omitted Oxford comma in state law. The law was soon amended to separate the last two items in a list of overtime pay exemptions to resolve the ambiguity (Victor, 2018).

- The inclusion or omission of the Oxford comma leads to two entirely different interpretations when names are listed. If you were to say, for instance, that you and two others must go to court, you would say, “Beth, Ian, and I must go to court.” Without the Oxford comma, however, you would be addressing Beth (who now isn’t going to court) to tell her that just you and Ian are going: “Beth, Ian and I must go to court,” which is not what you originally meant.

- Appositive relations between items in a series also create ambiguities when omitting the Oxford comma. If an actor winning a big award in front of a national audience were to say, “I would like to thank my parents, God and Buffy Sainte-Marie,” the absence of an Oxford comma makes “God and Buffy Sainte-Marie” appear to be an appositive noun phrase modifying “parents”—that is, she would imply that her parents are God and Buffy Sainte-Marie. By using the Oxford comma, she avoids this absurdity by thanking three entities: her parents, God, and Buffy Sainte-Marie—as intended.

- Omitting the Oxford comma is especially confusing if the items listed are a combination of paired and single items. If the list of pairs in the fourth correct example above omitted the Oxford comma, it would end with the absurdity of having the last four items appearing as singles with “and” awkwardly separating each: “. . . Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, Axl Rose and Slash and Anthony Kiedis and John Frusciante.” Knowing the context of these pairings would help resolve the ambiguity, but if you were reading a list of unknown mixed single and paired items, you wouldn’t know which was a single and which was a pair near the end without the Oxford comma. A list such as “A, B and C, D, E and F, G, H, I, J and K and L” would be ambiguous because you wouldn’t know if the last three items paired J with K (and L is single) or K with L (and J is single).

If the Oxford comma is necessary to avoid ambiguity in such cases, it should be used as a rule in all cases. Writers shouldn’t have to make a subjective judgment call about whether the reader would find it ambiguous with or without the Oxford comma because some readers are more astute than others. Except perhaps in titles where brevity is highly valued and no ambiguities of the kind listed above can confuse the reader, the Oxford comma should always be used.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for list of three or more words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence. If you don’t see a comma before the and that separates the last two items, add one there.

Incorrect:

Our group is full of non-contributors, my friend and me.

The fix:

Our group is full of non-contributors, my friend, and me.

Omitting the Oxford comma in the incorrect example above suggests that you and your friend are non-contributors because “my friend and me” are in appositive relation to “non-contributors.” Though you did not mean to say this, you are in effect offering yourself and your friend as particular examples of non-contributors. By adding the Oxford comma, however, you now say that the group is comprised of you, your friend, and some non-contributors. With the Oxford comma, you and your friend are productive members rather than non-contributors despite being grouped with them.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 4.2: Put commas between two or more coordinate adjectives.

Put commas between two or more coordinate adjectives that refer to the same noun. Coordinate adjectives are those stacked in front of a noun in no particular order to describe the noun in multiple ways. You can tell that they’re coordinate adjectives if you can (1) change their order and (2) add and between each without changing the meaning either way.

Correct:

The new hires turned out to be dedicated, ambitious employees.

Why it’s correct: Both adjectives, “dedicated” and “ambitious,” describe the noun “employees” in no particular order, and you can replace the comma with an and to make “. . . dedicated and ambitious employees.”

Correct:

Would you like a nice, new, clean, dry diaper?

Why it’s correct: All four coordinate adjectives describe the noun “diaper” in no particular order.

Correct:

The incessant, thunderous drum beat changed the rhythm of their hearts.

Why it’s correct: The comma goes between “incessant” and “thunderous” because they are coordinate. The comma doesn’t go between “thunderous” and “drum” because they are non-coordinate in that you can’t change their order and add and between them without changing the meaning.

Correct:

Use SMS for brief, fast text message exchanges.

Why it’s correct: The comma goes between “brief” and “fast” because they are coordinate. The comma doesn’t go after “fast,” “text,” or “message” because they are non-coordinate in that you can’t change their order and add and between them without changing the meaning.

How This Helps the Reader

The commas distinguish coordinate from non-coordinate adjectives, and therefore what adjectives are incidental and which are intrinsic qualities of the noun they describe. For more, see Commas: Coordinate Adjectives (Write, 2012) and Comma Tip 6: Use Commas Correctly with a Series of Adjectives (Simmons, 2018a).

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for a series of two or more adjectives preceding a noun without commas between them. If you can put and between them and change their order without changing the meaning of the sentence, they’re coordinate adjectives that need commas between them.

Incorrect:

The day started off with a vicious unrelenting freezing rain.

The fix:

The day started off with a vicious, unrelenting freezing rain.

The only adjectives that could be swapped around and have and added between them are “vicious” and “unrelenting.” The adjective “freezing” is locked in its position before the noun “rain” to mean the type of rain that makes the outside one huge ice rink. Therefore, you need to add a comma between “vicious” and “unrelenting,” but not between “unrelenting” and “freezing.”

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 4.3: Don’t put a comma after the final coordinate adjective.

Don’t put a comma after the second of two (or third of three, etc.) coordinate adjectives—i.e., between the final coordinate adjective and the noun it describes. See Comma Rule 4.2 above for a further explanation of coordinate vs. non-coordinate adjectives.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for coordinate adjectives preceding a noun with commas between them. If you can put and between them and change their order without changing the meaning of the sentence, they’re coordinate adjectives that need commas between them.

Incorrect:

Select and use common, basic, information technology tools to support communication.

The fix:

Select and use common, basic information technology tools to support communication.

The only adjectives that could be swapped around and have and added between them are “common” and “basic.” In this case, “information technology” (a.k.a. “IT”) is a noun phrase that modifies the noun “tools,” so their order is locked in, making them non-coordinate.

- Return to Quick Rules: Commas

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Comma Rule 4.4: Don’t put a comma between non-coordinate adjectives.

Don’t put commas between non-coordinate adjectives—that is, between adjectives that are in a fixed order before the noun they modify and cannot have and added between them without changing the meaning of the sentence. See Comma Rule 4.2 above for a further explanation of coordinate vs. non-coordinate adjectives.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for coordinate adjectives preceding a noun with commas between them. If you can’t put and between them and change their order without changing the meaning of the sentence, they’re non-coordinate adjectives. Any commas between them must be deleted.

Incorrect:

Send the black, Pearl, drum kit to the heavy, metal drummer.

The fix:

Send the black Pearl drum kit to the heavy metal drummer.

The order is important in the first set of non-coordinate adjectives describing the noun “kit” because the type of kit we’re dealing with is a drum kit, so “drum” must come immediately before “kit.” The brand of drum kit is Pearl (capitalized because it is a proper noun), so “Pearl” precedes “drum kit.” The only adjective preceding these non-coordinate adjectives is “black,” but it is unaccompanied by another to make it a coordinate adjective, so there are no commas. Likewise, inserting a comma between “heavy” and “metal” splits the musical genre “heavy metal” serving as a non-coordinate adjective to “drummer,” so it misleadingly implies that the drummer is a 400kg led statue.

Comma Rule 4.5: Don’t put commas between two coordinate nouns or verbs.

Don’t put commas between two nouns (or noun phrases) or verbs (or verb phrases) joined by the coordinating conjunction and in a compound subject, predicate, or object.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for commas appearing before or after the coordinating conjunction and when it comes between nouns (or noun phrases) or verbs (or verb phrases), then delete them.

Incorrect:

The communications director from your company, and the same from our company met to discuss a common strategy.

The Fix:

The communications director from your company, and the same from our company met to discuss a common strategy.

This above sentence features a compound subject, meaning that two subjects (the two communications directors) perform the main action (“met”). Though each is followed by a prepositional phrase (“from . . .”), the comma between them must be deleted in the incorrect sentence to avoid impeding the reader.

Incorrect:

They applied for an extension, and worked all weekend on the report.

The fix:

They applied for an extension and worked all weekend on the report.

The sentence above has a compound predicate, meaning that the one subject (“They”) performed two actions (“applied” and “worked”). Again, the comma is unnecessary between them and must be deleted from the incorrect sentence. The comma would be necessary if the second verb had a different subject performing the action, in which case they would be two independent clauses in a compound sentence (see Table 4.3.2b and Comma Rule 1.1).

Incorrect:

They can’t expect us to write both the report and memo, and not pay us.

The fix:

They can’t expect us to write both the report and memo but not pay us.

The above sentence also has a compound predicate (“can’t expect” and “not pay”). Adding a comma makes this out to be a compound sentence, which it isn’t because the subject “They” is common to both actions. To avoid an “X and Y and Z” structure caused by having a compound object (“report and memo”) appearing just before the conjunction coordinating the second verb, the “and” joining the two verb phrases can simply be changed to “but.”

Incorrect:

The teacher gave us a new deadline based on the revised schedule, and a slightly revised end-of-semester timeline.

The fix:

The teacher gave us a new deadline based on the revised schedule and a slightly revised end-of-semester timeline.

The above sentences have a compound object, meaning that two objects (“deadline” and “timeline”) are acted upon by the verb “gave.” The objects here are in somewhat long noun phrases, but to add a comma between them (after ”schedule”) would mislead the reader into thinking that this is a compound sentence with a new independent clause following “and.” Deleting the comma would ensure that the reader understands the sentence instead as a simple sentence with a compound object.

For more on commas, see the following resources:

- The Guide to Grammar and Writing’s Commas page, which includes a Comma Usage PowerPoint presentation and a Commas exercise (click on the image to the right; Darling, 2014e)

- Purdue OWL’s Extended Rules for Using Commas (Driscoll & Brizee, 2018) along with its Punctuation Exercises: Commas (Purdue OWL, 2010).

- The Punctuation Guide’s Comma page (Penn, 2011a)

- The Grammar Book’s Commas page and its Commas Quiz 1 and Commas Quiz 2 (Straus, 2018a)

Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

5.3.2: Apostrophes

Apostrophes are mainly used to indicate possession and contraction but are probably the most misplaced punctuation mark after commas. They can embarrass the writer who misuses them, show a lack of attention to detail, and confuse readers about whether a noun is singular or plural, possessive, a contraction, or just a misspelling. Used properly, apostrophes at the end of a noun cue readers that the noun following is possessed by what the noun preceding refers to. For instance, in “Uncle Tom’s cabin,” the apostrophe indicates that the cabin (noun) is owned by Uncle Tom. Placement of apostrophes before or after the s ending a word determines if the noun is plural or singular. They’re also used for contractions in informal writing such as you see at the beginning of this sentence. You have four main rules to follow when using apostrophes, as well as several special cases.

Quick Rules: Apostrophes

Click on the rules below to see further explanations, examples, advice on what to look for when proofreading, and demonstrations of how to correct common apostrophe errors associated with each one.

| Apostrophe Rule 1.1 | Put an apostrophe before the s ending a singular possessive noun.

Jenna’s goal is to find a money manager who can diversify her portfolio. |

| Apostrophe Rule 1.2 | Don’t put an apostrophe at the end of a simple plural noun.

Corben put on his glasses to see the looks on their faces. (no apostrophe at the end of “glasses,” “looks,” or “faces”). |

| Apostrophe Rule 2.1 | Put an apostrophe after the s ending a plural possessive noun.

All three companies’ bids for the contract were rejected. |

| Apostrophe Rule 2.2 | Don’t put an apostrophe before the s ending a non-possessive plural decade.

The corporation was in the black back in the 1940s. (no apostrophe between the 0 and s in “1940s”) |

| Apostrophe Rule 3 | Put an apostrophe where letters are omitted in contractions.

You’re saying that it’s not a mistake if they’re doing it twice? |

| Apostrophe Rule 4 | Put an apostrophe before a plural s following single letters

Mind your p’s and q’s, son. |

Extended Explanations

Apostrophe Rule 1.1: Put an apostrophe before the s ending a singular possessive noun.

Put an apostrophe before the s added to the end of a singular noun when the noun or noun phrase following belongs to the noun preceding it. In the case of joint ownership in compound nouns (when two or more nouns have joint possession of the noun following), the apostrophe-s goes only at the end of the second or final noun.

Correct:

Have you heard the story of Albert Einstein’s brain?

Why it’s correct: The brain belongs to Einstein (singular), so the apostrophe and s indicate possession.

Correct:

Grace Jones’s formidable presence in 1985’s A View to a Kill electrified audiences.

Why it’s correct: The “formidable presence” belongs to Grace Jones. Though her name ends with an s, she is grammatically singular and therefore receives an apostrophe and s just like any other singular noun. The apostrophe and s are also added to the end of years to indicate that the noun following (in this case a James Bond film) occurred in that year.

Correct:

I’ve always heeded my brother-in-law’s financial advice.

Why it’s correct: The apostrophe and s are added to the end of a compound noun.

Correct:

Reznor and Ross’s first soundtrack won a 2010 Oscar for Best Original Score.

Why it’s correct: The apostrophe and s are added to the end of the final noun in cases of joint possession. Saying “Reznor’s and Ross’s first soundtrack” would refer to solo soundtracks by each.

How This Helps the Reader

The apostrophe before the s signals to the reader that the preceding singular noun is in possession of the noun or noun phrase following. To test whether you are dealing with a case of possession, you can flip the order and insert “of the” between the nouns or noun phrases. In the first example above where the brain belongs to Einstein, for instance, “the brain of Einstein” is a wordier equivalent of “Einstein’s brain” but confirms possession.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for s added to the end of words when your intention is to show possession, but you’ve omitted the apostrophe, making the word look like a simple plural. Add the apostrophe. Also, in cases where an apostrophe is added to the very end of a singular noun that ends in s to show possession (see the second correct example above), add another s rather than imply that the singular noun is plural.

Incorrect:

Mr. Davis’ companies proposals request is for a 33% funding increase.

The fix:

Mr. Davis’s company’s proposal’s request is for a 33% funding increase.

The incorrect sentence above contains three apostrophe errors:

- The company belongs to Mr. Davis, who is just one person and is therefore grammatically singular despite having a name ending in s. Perhaps the writer heard that you can’t have an “s’s” due to pronunciation concerns, but usually we pronounce this Day-viss-ez to indicate possession. Thrown by this and confusing the singular and plural possessive forms, the writer who omits the s and may cause the same confusion can avoid doing so by adding it.

- The proposal belongs to the company, but the apostrophe is omitted and the plural form of company (“companies”) is given instead of “company’s.” The error is likely due to the fact that the plural noun and singular possessive noun forms are homophones—they sound exactly alike but are spelled differently and mean different things (see homophone.com for several examples of such homophones). Correcting this is a simple matter of replacing “ies” with “y’s” at the end of the word.

- Finally, the request is in the proposal and thus belongs to it. Omitting the apostrophe makes the plural noun “proposals,” and fixing it is just a matter of adding the apostrophe before the final s.

- Return to Quick Rules: Apostrophes

- Return to the Complete List of Punctuation Covered in This Chapter Section

Apostrophe Rule 2.1: Put an apostrophe after the s ending a plural possessive noun.

Put an apostrophe after the s at the end of a plural noun (a noun of two or more people, places, or things) when the noun or noun phrase following belongs to it.

Correct:

The two companies’ merger was finalized last month.

Why it’s correct: The apostrophe goes at the end of the plural noun “companies” to indicate that the noun following (“merger”) belonged to both.

Correct:

The Joneses’ family tradition includes rescuing ancient artifacts from dastardly villains.

Why it’s correct: The apostrophe is added to the end of “Joneses,” the plural of the surname “Jones,” meaning each individual Jones family member is in joint possession of the noun phrase following (“family tradition”).

Correct:

I listed having had three years’ experience in C++ coding on my résumé.

Why it’s correct: The apostrophe comes at the end of the plural “years” to indicate that the noun following happened in those years. This is a more concise alternative to saying “three years of experience.”

Exception:

When the plural form of the noun is irregular in that it doesn’t end in s (e.g., “feet,” “children,” “men,” “mice,” “teeth”), use the singular possessive apostrophe-s.

Correct:

Can you please point me to the men’s room?

Why it’s correct: The singular possessive apostrophe-s form is added to the end of an irregular plural noun that doesn’t end in s to indicate possession.

How This Helps the Reader