4.1: Choosing an Organizational Pattern

Learning Objectives

1. ENL1813 Course Learning Requirement 4: Use effective reading strategies to collect and reframe information from a variety of written materials accurately.

1. ENL1813 Course Learning Requirement 4: Use effective reading strategies to collect and reframe information from a variety of written materials accurately.

i. Identify the organizational structure of a variety of written messages (ENL1813BGPST CLR 4.1)

ii. Separate main ideas from subordinate ideas in written materials (ENL1813BHMST CLR 4.1)

3. ENL1813 Course Learning Requirement 1: Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

i. Apply standard patterns of organization (ENL1813GP CLR 1.3)

ii. Recognize and use basic patterns of standard English (ENL1813HIMST CLR 1.3)

The shape of your message depends on the purpose you set out to achieve, which is why we said in §2.1 above that a clearly formulated purpose must be kept in mind throughout the writing process. Whether your purpose is to inform, instruct, persuade, or entertain, structuring your message according to set patterns associated with each purpose helps achieve those goals. Without those familiar structures guiding your reader toward the intended effect, your reader can get lost and confused, perhaps reflecting the confusion in your own mind if your thoughts aren’t clearly focused and organized enough themselves. Or perhaps your message is crystal clear in your own mind, but you articulate it in an unstructured way that assumes your reader sees what you think is an obvious main point. Either way, miscommunication results because your point gets lost in the noise. Lucky for us, we have standard patterns of organization to structure our thoughts and messages to make them understandable to our audiences.

From paragraphs to essays to long reports, most messages follow a three-part structure that accommodates the three-part division of our attention spans and memory:

- Attention-grabbing opening

- The job of the opening is to hook the reader in to keep reading, capturing their attention with a major personal takeaway (answering the reader’s question “What’s in it for me?”) or the main point (thesis) of the message. In longer messages, the opening includes an introduction that establishes the frame in which the reader can understand everything that follows.

- This accommodates the primacy effect in psychology, which is that first impressions tend to stick in our long-term memory more than what follows (Baddeley, 2000, p. 79), whether those impressions are of the people we meet or the things we read. You probably remember what a recently made friend at college looked like and said the first time you met them, for instance, despite that happening weeks or even months ago. Likewise, you will recall the first few items you read in a list of words (like those in Table 2.2.3 above) better than those in the middle. This effect makes the first sentence you write in a paragraph or the first paragraph you write in a longer message crucial because it will be what your reader remembers most and the anchor for their understanding of the rest. Because of the way our minds work, your first sentence and paragraph must represent the overall message clearly.

- Detail-packed body

- The message body supports the opening with further detail supporting the main point. Depending on the type of message and organizational structure that suits it best, the body may involve:

- Evidence in support of a thesis

- Background for better understanding

- Detailed explanations and instructions

- Convincing rationale in a persuasive message

- Plot and character development in an entertaining story

This information is crucial to the audience’s understanding of and commitment to the message, so it cannot be neglected despite the primacy and recency effects.

- Our memory typically blurs these details, however, so having them written down for future reference is important. You don’t recall the specifics of every interaction with your closest friend in the days, months, and years between the strong first impression they made on you and your most recent memory of them, but those interactions were all important for keeping that relationship going, and certainly some highlight memories from throughout that intervening time come to mind. Likewise, the message body is a collection of important subpoints in support of the main point, as well as transitional elements that keep the message coherent and plot a course towards its completion.

- Wrap-up and transitional closing

- The closing completes the coverage of the topic and may also point to what’s next, either by bridging to the next message unit (e.g., the concluding sentence of a paragraph establishes a connection to the topic of the next paragraph) or offering cues to what action should follow the message (e.g., what the reader is supposed to do in response to a letter, such as reply by a certain date).

- Depending on the size, type, and organizational structure of the message, the closing may also offer a concluding summary of the major subpoints made in the body to ensure that the purpose of the message has been achieved. In a persuasive message, for instance, this summary helps prove the opening thesis by confirming that the body of evidence and argument supported it convincingly.

- The closing appeals to what psychologists call the recency effect, which is that, after first impressions, last impressions stick out because, after the message concludes, we carry them in our short-term memory more clearly than what came before (Baddeley, 2000, p. 79). Just as you probably remember your most recent interaction with your best friend—what they were wearing, saying, feeling, etc.—so you remember well how a message ends.

The effective writer therefore loads the message with important points both at the opening and closing because the reader will focus on and remember what they read there best, as well as organizes the body in a manner that is engaging and easy to follow. In the next section, we will explore some of the possibilities for different message patterns while bearing in mind that they all follow this general three-part structure. Learning these patterns is valuable beyond merely being able to write better. Though a confused and scattered mind produces confusing and disorganized messages, anyone can become a more clear and coherent thinker by learning to organize messages consistently according to well-established patterns.

4.1.1: Direct Messages

Because we’re all going to die and life is short, most messages do their reader a solid favour by taking the direct approach or frontloading the main point, which means getting right to the point and not wasting precious time. In college and in professional situations, no one wants to read or write more than they have to when figuring out a message’s meaning, so everybody wins when you open with the main point or thesis and follow with details in the message body. If it takes you a while before you find your own point in the process of writing, leaving it at the end where you finally discovered what your point was, or burying it somewhere in the middle, will frustrate your reader by forcing them to go looking for it. If you don’t move that main point by copying, cutting, and pasting it at the very beginning, you risk annoying your busy reader because it’s uncomfortable for them to start off in the weeds and linger in a state of confusion until they finally find that main point later. Leaving out the main point because it’s obvious to you—though it isn’t at all to the reader coming to the topic for the first time—is another common writing error. The writer who frontloads their message, on the other hand, finds themselves in their readers’ good graces right away for making their meaning clear upfront, freeing up readers to move quickly through the rest and on to other important tasks in their busy lives.

Whether or not you take the direct approach depends on the effect your message will have on the reader. If you anticipate your reader being interested in the message or their attitude to it being anywhere from neutral to positive, the direct approach is the only appropriate organizational pattern. Except in rare cases where your message delivers bad news, is on a sensitive topic, or when your goal is to be persuasive (see §4.1.2 below), all messages should take the direct approach. Since most business messages have a positive or neutral effect, all writers should frontload their messages as a matter of habit unless they have good reason to do otherwise. The three-part message organization outlined in the §4.1 introduction above helps explain the psychological reasons why frontloading is necessary: it accommodates the reader’s highly tuned capacity for remembering what they see first, as well as respects their time in achieving the goal of communication, which is understanding the writer’s point.

Let’s say, for instance, that you send an email to a client with e-transfer payment instructions so that you can be paid for work you did for them. Because you send this same message so often, the objective and context of this procedure is so well understood by you that you may fall into the trap of thinking that it goes without saying, so your version of “getting to the point” is just to open with the payment instructions. Perhaps you may have even said in a previous email that you’d be sending payment instructions in a later email, so you think that the reader knows what it’s about, or you may get around to saying that this is about paying for the job you did at the end of the email, effectively burying it under a pile of details. Either way, to the reader who opens the email to see a list of instructions for a procedure they’ve never done before with no explanation as to why they need to do this and what it’s all for exactly, confusion abounds. At best the client will email you back asking for clarification; at worst they will just ignore it, thinking that it was sent in error and was supposed to go to someone who would know what to do with it. You’ll have to follow up either way, but you have better things to do. If you properly anticipated your audience’s reaction and level of knowledge as discussed in Step 1.2 of the writing process (see §2.2.4 above), however, you would

know that opening with a main point like the following would put your client in the proper frame of mind for following the instructions and paying you on time:

Please follow the instructions below for how to send an e-transfer payment for the installation work completed at your residence on July 22.

In the above case, the opening’s main point or central idea is a polite request to follow instructions, but in other messages it may be a thesis statement, which is a summary of the whole argument; in others it may be a question or request for action. The main point of any message, no matter what type or how long, should be an idea that you can state clearly and concisely in one complete sentence if someone came up to you and asked you what it’s all about in a nutshell. Some people don’t know what their point is exactly when they start writing, in which case writing is an exploratory exercise through the evidence assembled in the research stage. As they move toward such a statement in their conclusion, however, it’s crucial that they copy, cut, and paste that main point so that it is among the first—if not the first—sentence the reader sees at the top of the document, despite being among the last written.

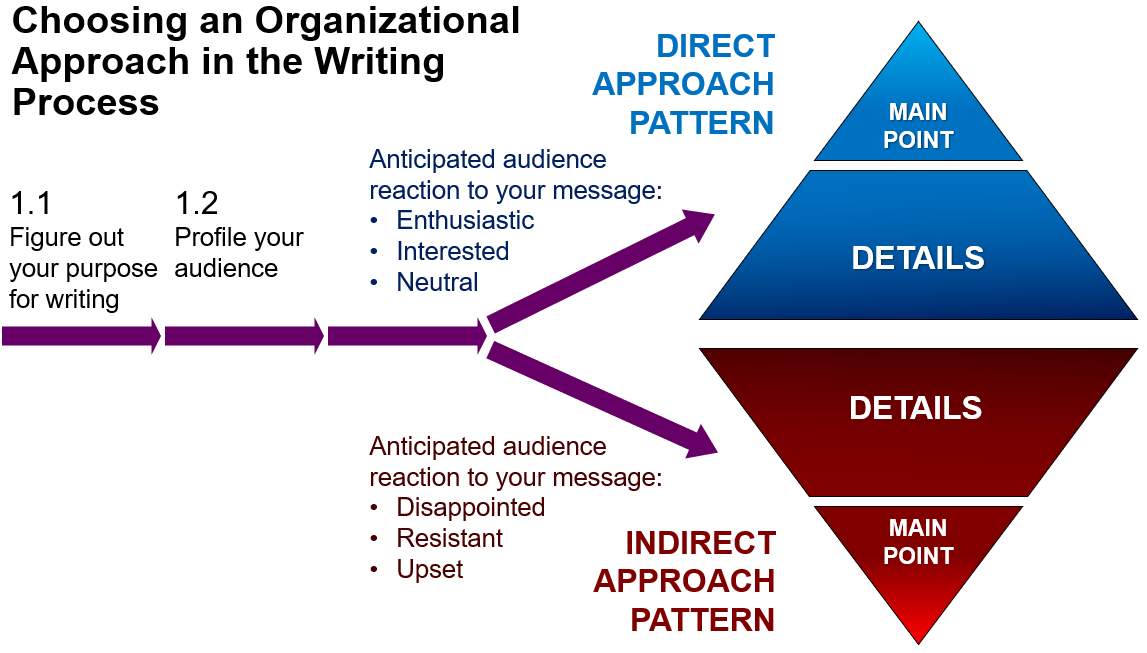

Figure 4.1.1: Choosing an organizational approach in the writing process

- 1.1: Figure out your purpose for writing

- 1.2: Profile your audience

- Direct Approach Pattern: Anticipated audience reaction to your message is enthusiastic, interested or neutral

- Main Point

- Details

- Indirect Approach Pattern: Anticipated audience reaction to your message is disappointed, resistant or upset

- Details

- Main Point

4.1.2: Indirect Messages

While the direct approach leads with the main point, the indirect approach strategically buries it deeper in the message when you expect that your reader will be resistant to it, displeased with it, upset or shocked by it, or even hostile towards it. In such cases, the direct approach would come off as overly blunt, tactless, and even cruel by hitting the reader over the head with it in the opening. The goal of indirect messages is not to deceive the reader nor make a game of finding the main point, but instead to use the opening and some of the message body to ease the reader towards an unwanted or upsetting message by framing it in such a way that the reader becomes interested enough to read the whole message and is in the proper mindset for following through on it. This organizational pattern is ideal for two main types of messages: those delivering bad news or addressing a sensitive subject, and those requiring persuasion such as marketing messages pitching a product, service, or even an idea. Both types are the focus of the two final sections of Chapter 9 respectively (see §9.4 and §9.5).

For now, however, all we need to know is that the organization of a persuasive message follows the so-called AIDA approach, which divides the message body in the traditional three-part organization into two parts, making for a four-part structure:

- Attention-grabbing opener

- Interest-generating follow-up

- Desire-building details

- Action cue

Nearly every commercial you’ve ever seen follows this general structure, which is designed to keep you interested while enticing you towards a certain action such as buying a product or service. If a commercial took the direct approach, it would say upfront “Give us $19.99 and we’ll give you this turkey,” but you never see that. Instead you see all manner of techniques used to grab your attention in the opening, keep you tuned in through the follow-up, pique your desire in the third part, and get you to act on it with purchasing information at the end. Marketing relies on this structure because it effectively accommodates our attention spans’ need to be hooked in with a strong first impression and told what to do at the end so that we remember those details best, while working on our desires—even subconsciously—in the two-part middle body.

Likewise, a bad-news message divides the message body into two parts with the main point buried in the second of them (the third part overall), with the opening used as a hook that delays delivery of the main point and the closing giving action instructions as in persuasive AIDA messages. The typical organization of a bad-news message is:

- Buffer offering some good news, positives, or any other reason to keep reading

- Reasons for the bad news about to come

- Bad news buried and quickly deflected towards further positives or alternatives

- Action cue

Delaying the bad news till the third part of the message manages to soften the blow by surrounding it with positive or agreeable information that keeps the audience reading so that they miss neither the bad news nor the rest of the information they need to understand it. If a doctor opened by saying “You’ve got cancer and probably have six months to live,” the patient would probably be reeling so much in hopelessness from the death-sentence blow that they wouldn’t be in the proper frame of mind to hear important follow-up information about life-extending treatment options. If an explanation of those options preceded the bad news, however, the patient would probably walk away with a more hopeful feeling of being able to beat the cancer and survive. Framing is everything when delivering bad news.

Consider these two concise statements of the same information taking both the direct and indirect approach:

Table 4.1.2: Comparison of Direct and Indirect Messages

| Direct Message | Indirect Message |

|---|---|

| Global Media is cutting costs in its print division by shutting down several local newspapers. | Global Media is seeking to improve its profitability across its various divisions. To this end, it is streamlining its local newspaper holdings by strengthening those in robust markets while redirecting resources away from those that have suffered in the economic downturn and trend towards fully online content. |

Here we can see at first glance that the indirect message is longer because it takes more care to frame and justify the bad news, starting with an opening that attempts to win over the reader’s agreement by appealing to their sense of reason. In the direct approach, the bad news is delivered concisely in blunt words such as “cutting” and “shutting,” which get the point across economically but suggest cruel aggression with violent imagery. The indirect approach, however, makes the bad news sound quite good—at least to shareholders—with positive words like “improve,” “streamlining,” and “strengthening.” The good news that frames the bad news makes the action sound more like an angelic act of mercy than an aggressive attack. The combination of careful word choices and the order in which the message unfolds determines how well it is received, understood, and remembered as we shall see when we consider further examples of persuasive and bad-news messages later in §9.4 and §9.5.

4.1.3: Organizing Principles

Several message patterns are available to suit your purposes for writing in both direct and indirect-approach message bodies, so choosing one before writing is essential for staying on track. Their formulaic structures make the job of writing as easy and routine as filling out a form—just so long as you know which form to grab and have familiarized yourself with what they look like when they’re filled out. Examples you can follow are your best friends through this process. By using such organizing principles as chronology (a linear narrative from past to present to future), comparison-contrast, or problem-solution, you arrange your content in a logical order that makes it easy for the reader to follow your message and buy what you’re selling.

If you undertake a large marketing project like a website for a small business, it’s likely that you’ll need to write pieces based on many of the available organizing principles identified, explained, and exemplified in Table 4.1.3 below. For instance, you might:

- Introduce the product or service with a problem-solution argument on the homepage

- Include a history of the company told using the chronological form as well as the journalistic 5W+H (who, what, where, when, why, and how) breakdown on the About page; you may also include short biographies of key staff

- Use technical descriptions and a comparison-contrast structure for product or service explanations that distinguish what you offer from your competitors

- Provide short research articles or essays on newsworthy topics related to your business in the general-to-specific pattern on the Blog page

- Provide point-pattern questions and answers on the FAQ page, such as the pros and cons of getting a snow-removal service in answer to the question of whether to pay someone to do it for you

- Provide instructions for setting up service on the Contact page

Checking out a variety of websites to see how they use these principles effectively will provide a helpful guide for how to write them yourself. So long as you don’t plagiarize their actual wording (see §3.5.1 above for why you mustn’t do this and §3.4.2 for how to avoid it), copying their basic structure so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel means that you can provide readers with a recognizable form that will enable them to find the information they need.

Table 4.1.3: Ten Common Organizing Principles

| Organizing Principle | Structure & Use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Chronology & 5W+H |

|

Wolfe Landscaping & Snowblowing began when founder Robert Wolfe realized in 1993 that there was a huge demand for reliable summer lawncare and winter snow removal when it seemed that the few other available services were letting their customers down. Wolfe began operations with three snow-blowing vehicles in the Bridlewood community of Kanata and expanded to include the rest of Kanata and Stittsville throughout the 1990s.

WLS continued its eastward expansion throughout the 2000s and now covers the entire capital region as far east as Orleans, plus Barrhaven in the south, with 64 snow-blowing vehicles out on the road at any one time. WLS recently added real-time GPS tracking to its app service and plans to continue expanding its service area to the rural west, south, and east of Ottawa throughout the 2020s. |

| 2. Comparison & Contrast |

|

Wolfe Snowblowing goes above and beyond what its competitors offer. While all snowblowing services will send a loader-mount snow blower (LMSB) to your house to clear your driveway after a big snowfall, Wolfe’s LMSBs closely follow the city plow to clear your driveway and the snow bank made by the city plow in front of it, as well as the curbside area in front of your house so you still have street parking.

If you go with the “Don’t Lift a Finger This Winter” deluxe package, Wolfe will additionally clear and salt your walkway, stairs, and doorstep. With base service pricing 10% cheaper than other companies, going with Wolfe for your snow-removal needs is a no-brainer. |

| 3. Pros & Cons |

|

Why would you want a snow-removal service?

Advantages include:

The disadvantages of other snow-removal services include:

As you can see, the advantages of WLS outweigh the disadvantages for any busy household. |

| 4. Problem & Solution |

|

Are you fed up with getting all geared up in -40 degree weather at 6am to shovel your driveway before leaving for work? Fed up with finishing shoveling the driveway in a hurry, late for work in the morning, and then the city plow comes by and snow-banks you in just as you’re about to leave? Fed up with coming home after a long, hard day at work only to find that the city plow snow-banked you out?

Well worry no more! Wolfe Landscaping & Snowblowing has got you covered with its 24-hour snow removal service that follows the city plow to ensure that you always have driveway access throughout the winter months. |

| 5. Cause & Effect |

|

As soon as snow appears in the weather forecast, Wolfe Landscaping & Snowblowing reserves its crew of dedicated snow blowers for 24-hour snow removal. When accumulation reaches 5cm in your area, our fleet deploys to remove snow from the driveways of all registered customers before the city plows get there. Once the city plow clears your street, a WLS snow blower returns shortly after to clear the snow bank formed by the city plow at the end of your driveway. |

| 6. Process & Procedure |

|

Ordering our snow removal service is as easy as 1 2 3:

|

| 7. General to Specific |

|

Wolfe Landscaping & Snowblowing provides a reliable snow-removal service throughout the winter. We got you covered for any snowfall of 5cm or more between November 1st and April 15th. Once accumulation reaches 5cm at any time day or night, weekday or weekend, holiday or not, we send out our fleet of snow blowers to cover neighbourhood routes, going house-by-house to service registered customers. At each house, a loader-mount snow blower scrapes your driveway and redistributes the snow evenly across your front yard in less than five minutes. |

| 8. Definition & Example |

|

A loader-mount snow blower (LMSB) is a heavy-equipment vehicle that removes snow from a surface by pulling it into a front-mounted impeller with an auger and propelling it out of a top-mounted discharge chute. Our fleet consists of green John Deere SB21 Series and red M-B HD-SNB LMSBs. |

| 9. Point Pattern |

|

Wolfe Landscaping & Snowblowing’s “Don’t Lift a Finger This Winter” deluxe package ensures that you will always find your walkway and driveway clear when you exit your home after a snowfall this winter! It includes:

|

| 10. Testimonial |

|

According to Linda Sinclair in the Katimavik neighbourhood, “Wolfe did a great job clearing our snow this past winter. We didn’t see them much because they were always there and gone in a flash, but the laneway was always scraped clear by the time we left for work in the morning if it snowed in the night. We never had a problem when we got home either, unlike when we used Sherman Snowblowing the year before and we always had to stop, park on the street, and shovel the snow bank made by the city plow whenever it snowed while we were at work. Wolfe was the better service by far.” |

Though shorter documents may contain only one such organizing principle, longer ones typically involve a mix of different organizational patterns used as necessary to support the document’s overall purpose.

Key Takeaways

Before beginning to draft a document, let your purpose for writing and anticipated audience reaction determine whether to take a direct or indirect approach, and choose an appropriate organizing principle to help structure your message.

Before beginning to draft a document, let your purpose for writing and anticipated audience reaction determine whether to take a direct or indirect approach, and choose an appropriate organizing principle to help structure your message.

Exercises

1. Consider some good news you’ve received recently (or would like to receive if you haven’t). Assuming the role of the one who delivered it (or who you would like to deliver it), write a three-part direct-approach message explaining it to yourself in as much detail as necessary.

1. Consider some good news you’ve received recently (or would like to receive if you haven’t). Assuming the role of the one who delivered it (or who you would like to deliver it), write a three-part direct-approach message explaining it to yourself in as much detail as necessary.

2. Consider some bad news you’ve received recently (or fear receiving if you haven’t). Write a four-part indirect-approach message explaining it to yourself as if you were the one delivering it.

3. Draft a three-paragraph email to your boss (actual or imagined) where you recommend purchasing a new piece of equipment or tool. Use the following organizational structure:

i. Frontload your message by stating your purpose for writing directly in the first sentence or two.

ii. Describe the problem that the tool is meant to address in the follow-up paragraph.

iii. Provide a detailed solution describing the equipment/tool and its action in the third paragraph.

4. Picture yourself a few years from now as a professional in your chosen field. You’ve been employed and are getting to know how things work in this industry when an opportunity to branch out on your own presents itself. To minimize start-up costs, you do as much of the work as you can manage yourself, including the marketing and promotion. To this end, you figure out how to put together a website and write the content yourself. For this exercise, write a piece for each of the ten organizing principles explained and exemplified in Table 4.1.3 above and about the same length as each, but tailored to suit the products and/or services you will be offering in your chosen profession.

References

Baddeley, A. (2000). Short-term and working memory. In E. Tulving & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Memory (pp. 77-92). New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?id=DOYJCAAAQBAJ