9.2 Theories of Substance Use / Addiction

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Explore various theories of substance use

- Compare and contrast theories

- Discuss how theories impact service provision and prevention initiatives

There are many theories that hope to explain why individuals use and abuse substances. Theories can also help with interventions, treatment, prevention, relapse and recovery.

We will be exploring substance use disorders as a biopsychosocial phenomenon and unpack biological, psychological and social theories of substance abuse. You may choose to explore other theories, there are links to multiple theories of substance use disorders in additional resources.

We will start by an overview on theories below. Watch Orientation to Theories of Substance Misuse

Orientation to Theories of Substance Misuse. By Council on Social Work Education. Orientation to Theories of Substance Misuse was developed and recorded by Dr. Audrey Begun, MSW, PhD, The Ohio State University, in February 2021(1).

Transcript

The concept of substance use disorders has evolved. While a moral model is still prevalent in much of the population, there has been a shift in the medicalization of addressing substance use disorders. The moral model is based on the belief that using substances is a moral failing, related only to individual issue “using any drug is unacceptable, wrong, and even sinful.(2) Other theories include a biological theory, which suggests it may be the chemistry in our brain or our genetics that makes us susceptible to substance use. There is no one theory that can explain substance use for every person with a substance use disorder: “not everything that counts can be counted, and the healing that involves the making whole of a life involves not seeing different things but seeing everything differently”.(3) When we understand these theories and use them together, this is called a biopsychosocial approach and western treatment models generally “implicates numerous biological, psychological and social factors as playing a part in the development of addiction. Consequently, it is considered that all three domains must be considered in treatment”.(4)

Understanding theories is important as you will be exploring treatment, prevention and recovery, as well as harm reduction. A theory can help explain a phenomenon like substance use. You do not need to be an expert on theories; however, it is important to understand the theories and begin to explore your own beliefs about substance use and process addiction. Exploring theories will help broaden your understanding, and through exploring theories you will have an opportunity to determine what connects for you. This means the services you provide may rely on one theory or multiple theories. For example, Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous use a spiritual model, which sees substance use and substance use disorders as a spiritual deficit(5) and focus on bringing a spiritual component to treatment; “there is a power greater than us as individuals”.(6)

While there are many theories about substance use, this chapter should help you to understand why some people misuse substances. We will start with watching the video below which provides an exploration of some of the more prevalent theories of substance use.(7)

Theories of Addiction. By Doc Snipes. Dr. Dawn-Elise Snipes is a Licensed Professional Counselor and Qualified Clinical Supervisor. This video speaks about Theories of Addiction

Transcript

ACTIVITIES

- Review the various theories of addiction identified by ALLCEU Counselling (2012). What, if anything, is missing?

- Compare and contrast two theories.

- Pick the theories you most closely align with.

- Can any theory stand alone on its own? Why? Why not?

All these theories separately create a narrower view of substance use and influence how we treat substance use disorders. As our understanding of substance use and substance use disorders continues to evolve, using a perspective which includes an intersectional approach may help us to address some of the societal inequities that put people and communities at risk of substance use disorders. We must be cautious to acknowledge there is no panacea, nor any magic bullet. Substance use is a reality; and Wright(8) suggests “if addiction is ‘always already’ part of the metaphysics of western culture, it can be hard to be analytical about specific effects at specific times”.(9) This means that substance use is engrained in much of Canadian culture from celebrations to daily life and using one lens in one moment to explore substance use is not effective. Theories are one piece of a complicated puzzle.

Moral theory

Where does a moral approach to substance use come from? Wright(10) suggests our current moral judgments of addiction begin with a Victorian politic, when “modern man begins to worry that any weakness of moral fiber in the exercise of self-restraint could lead him rapidly away from industry and towards indolence and even idiocy, by way of the bottle, the pipe or the syringe”.(11) There are examples of the moral model in Canada, including prohibition and the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, as well as the Criminal Code of Canada. The moral model suggests using a substance is a moral failing which will lead to a path of destruction. It views people who use substances as having a choice to use substances and judges them for using the substances.

Listen to the short podcast below.(12) Note the language used. Is this podcast stigmatizing?

Food For Thought

- Reflect for a moment on stigma as we discussed in Chapter 2.

- How can you relate the stigma of substance use to the moral model?

- What are some examples?

- How could you help others understand the moral model?

The stigma associated with substance use is so prevalent, a recent review by the World Health Organization concluded out of all health disorders, substance use and process addiction disorders were the most stigmatized.(13)Think about the language used to describe substance use disorders and the people who live with them. Stigma and the moral model go hand in hand. “A large body of research indicates that this stigma is persistent, pervasive, and rooted in the belief that addiction is a personal choice reflecting a lack of willpower and a moral failing”.(14) The moral model still exists today when you hear statements like “pull up your bootstraps,” or “get over it,” when talking about a substance use disorder. It seeks to place blame on the person with the substance use disorder. This can impact individuals who use substances, who may see themselves as having failed, especially when it comes to treatment and recovery.

The following video may help you understand how some view substance use.(15)

Nuggets. By Filmbilder & Friends. Kiwi tastes a golden nugget. It’s delicious.

Transcript

Food For Thought

- Reflect on Nuggets

- What do you think this video promotes (abstinence, prevention, harm reduction, recovery?) Why?

- Is this video helpful in explaining substance use?

Treatment methods generally have moved beyond a moral model. For example, programs that offer a harm reduction approach are a direct challenge to the moral model, as they offer a lack of judgment and support people “where they are,” embracing the stages of change and allowing for engagement at each level of pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and relapse.

ACTIVITIES

- Review the Government of Canada’s Background Document strengthening-canada-approach-substance-use-issue

- Can you find examples of moral theory?

The field of Social Services is working to move beyond a moral model of substance use disorders. You can help people make their own decisions (self-efficacy) and advocate for services to improve the lives of people who use substances and live with SUDs.

Biological theory

Some researchers believe that substance use disorders are a biological phenomenon; “efforts to target addictions require consideration of how the improved biological understanding of addictions may lead to improved prevention, treatment and policy initiatives”(16). The biological theory of substance use helps us understand how substances impact our brain and the changes that happen. Please watch the following short video on how substances impact the brain.(17)

The Biology of Addiction: Killing Pain: Addiction tends to masquerade as bad behavior. The more we learn about how the brain is chemically altered because of substances like opioids, the more we can see how physiologically our brains are “re-wired”, making addiction a disease of the brain.Episode 2. By Killing Pain.

Transcript

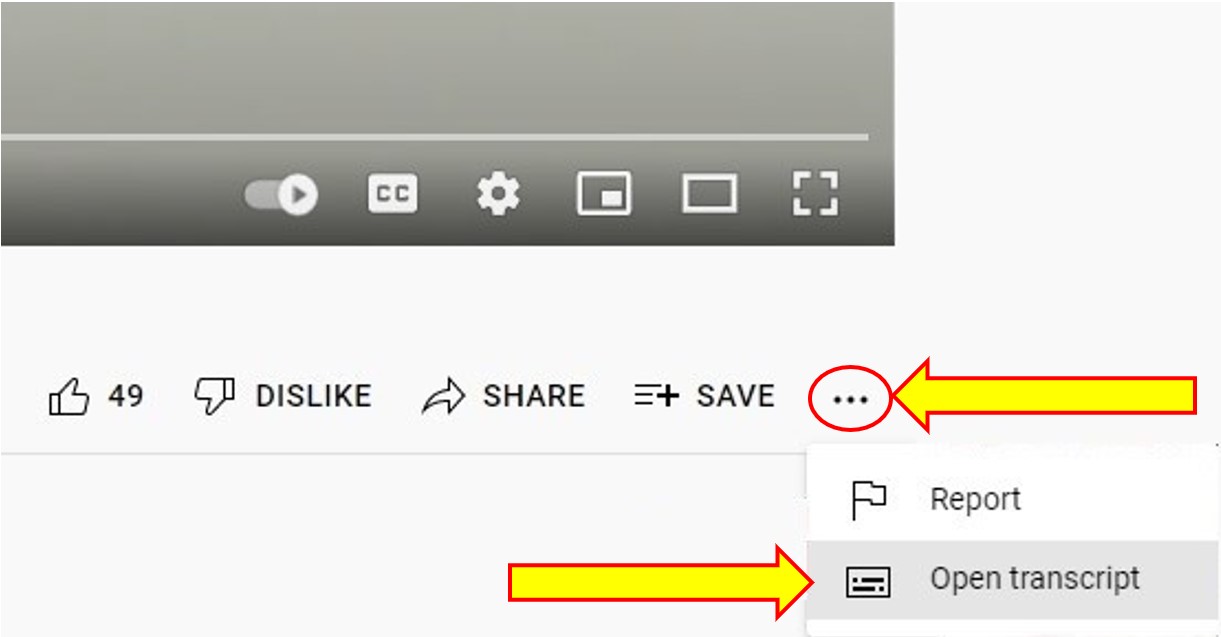

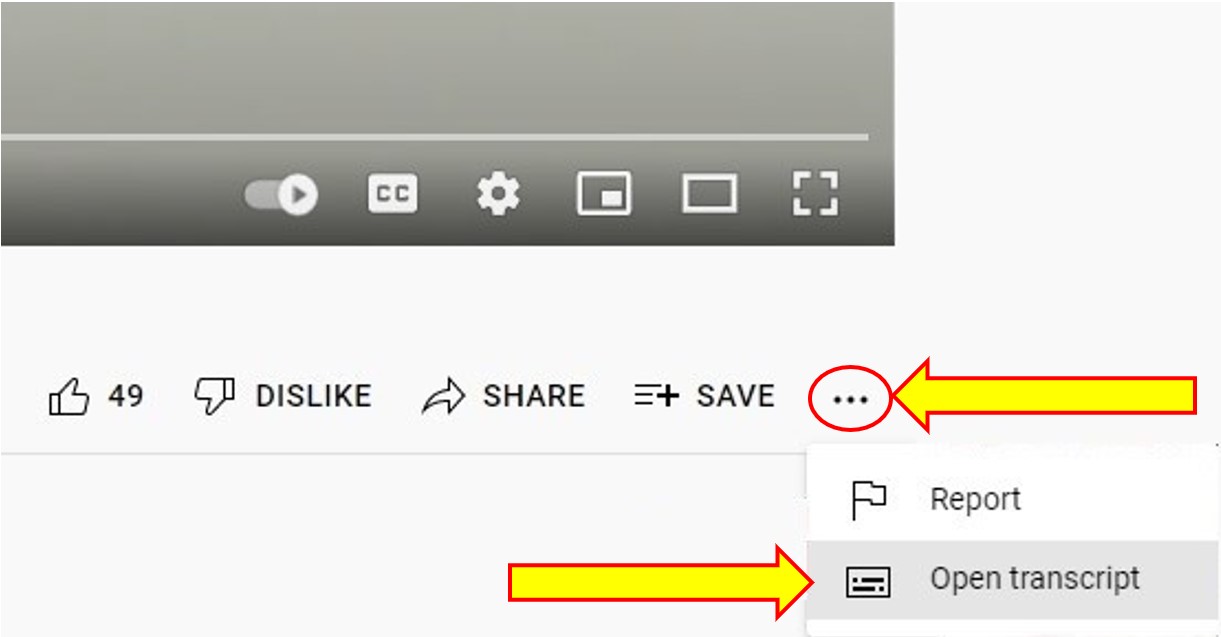

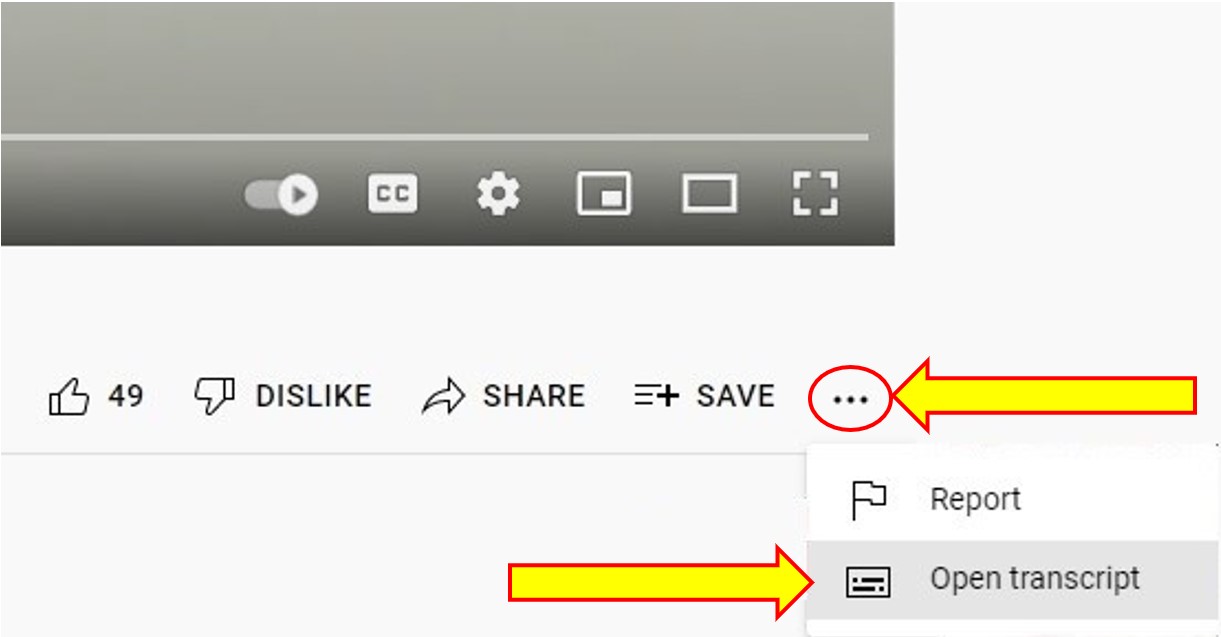

To Access the Video Transcript:

1. Click on “YouTube” on the bottom-right of the video. This will take you directly to the YouTube video.

2. Click on the More Actions icon (represented by three horizontal dots)

3. Click on “Open Transcript”

If you think about any activity you participate in, if it makes you feel good, chances are that when you participate your brain is releasing dopamine. If you remember we learned dopamine is a neurotransmitter that impacts the reward centre of the brain. Your brain typically releases dopamine when you participate in behaviours or activities that make you feel good. This is released each time you repeat a behaviour.

Food For Thought

- What are the activities you participate in that give you a pleasant feeling?

- How often do you participate in those activities?

- Why do you think these activities make you feel good beyond the dopamine release?

When you take a substance, especially opiates, your brain releases dopamine. Every time you take that substance, your brain, and the dopamine it produces are remembering that “feel good” feeling and reinforcing it. For a person living with a substance use disorder, every time they use a substance it triggers adaptations in dopamine production. Using a biological theory to explore how substances impact the brain can help with the development of treatment that focuses specifically on the brain. For example, Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) is a treatment that focuses on the biology of an opiate use disorder and benzodiazepines have been used to target the biology of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.(18)

We can use biological theory to help us understand the vulnerabilities of some to a substance use disorder. What is a vulnerable individual? A vulnerable individual may be someone who has a unique physiology (mental health disorder, brain disorder, or physical disorder). Certain groups, particularly adolescents and young adults, may be vulnerable to developing a substance use disorder at certain ages, due to the stages of brain development. Specific brain regions, like the amygdala typically mature slower, impacting decision making, which may be a reason why some youth struggle with substance use.(19)

Mental health also plays a role in substance use. Many studies suggest and confirm those with mental health use substances to manage their day-to-day challenges due to their illness.(20) Vulnerable individuals may also be people who have a genetic predisposition (a parent or a close family member who has struggled with a substance use disorder). For example, numerous family studies, adoption studies, and twin studies suggest genetics plays a role.(21) Many of these studies however do not allow us to separate the effects of genetic and environmental influences.(22) This means that substance use disorders from a genetic perspective should not be considered simply a biological phenomenon.

Despite significant advances in our understanding of the biological bases of substance use disorders; we know substance use disorders continue to represent a huge public health crisis,(23) and further research in this area must continue as we support individuals living with a substance use disorder. Every brain, and every person is different; we must look at biology as one potential factor in a substance use disorder.

Psychological Theories

Using psychology also helps us understand substance use disorders. There are a variety of psychological approaches that help us understand behaviours, treatment, and recovery. Psychological theory can look at behaviour. For example, helpers may look at how and why the behaviour is maintained; they may also engage in understanding the behaviours that are happening while a person is under the influence of a substance (24).

Learning theory is another example of a psychological theory. Learning theory suggests that a substance use disorder results from the learning we receive from the social environment, our experiences. For example, observing a peer or parent smoke or vape may influence whether a young person also begins smoking or vaping. Is the child or youth seeing a positive or a negative experience in the substance use? These observations “can instill positive expediencies for the effects of these substances and provide models that show how to obtain and use them”.(25)

Food For Thought

- What is something you do when you are happy?

- Why do you do this?

- When you reflect on this activity, where do you think you learned this?

- How many activities do you engage in that you learned from others?

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are two types of learning models. When we use classical conditioning in the field of substance use disorders, we examine the relationship between the substance use and its connection with the environment. For example, let us examine smoking tobacco.

ACTIVITIES

- Brainstorm a list of reasons why people smoke

- Brainstorm a list of reasons why people quit

- If you were to use classical conditioning to understand how to support someone who was quitting, what might you consider based on your answers above?

Classical conditioning helps individuals understand their relationship with a substance and how they may crave a particular substance based on their environment. For example, someone who smokes tobacco may feel a pleasant feeling every time they visit a particular store, as that is the store where they buy cigarettes from, and often smoke as soon as they leave the store. There are numerous resources to help a person quit smoking based on classical conditioning. These resources help individuals identify “triggers” or activators, they look at factors that can make someone feel like they need to use a substance, because of their relationship to the environment. “Common triggers that bring-on cravings include drinking coffee or alcohol, relaxing after work or after a meal, talking on the phone, driving, feeling stressed or angry”(26) Using classical conditioning, you can examine activators and help an individual identify strategies to reduce the emotions associated with the activators. These activators or cravings will reduce over time, the more a person is able to engage with the environment without using the substance.

Operant conditioning uses the concept of rewards and punishments. If a person uses a substance, there are biological changes that happen. For some it is a pleasant feeling, for others, it is unpleasant. Not every person who uses a substance will develop a disorder; for some the pleasant feeling is just that, a pleasant feeling. For others the pleasant feeling takes over, and the reward becomes the focus.

This focus can then develop into a substance use disorder. The Community Reinforcement Approach builds on operant conditioning; “the goal of CRA is to help people discover and adopt a pleasurable and healthy lifestyle that is more rewarding than a lifestyle filled with using alcohol or drugs”.(27) Please read this primer on the Community Reinforcement Approach by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.(28)

This type of conditioning has also been seen in television programs like Intervention Canada, where family members stage an intervention with the person using substances and give the individual an “ultimatum.” Operant conditioning can be highly effective; however, interventions which focus on punishment rarely lead to a life without substances. Confrontation is highly ineffective in decreasing the use of alcohol and other substance.(29)

Psychological theories of substance use are varied and may help you explore how to best serve the individuals you will be working with.

READ

For more information on psychological theories review Chapter 4: Psychological Models of Substance Misuse in Introduction to Substance Use Disorders by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun. CC BY-NC

Social Theories

We live in a complex world with many factors that influence our behaviours. We learn from many areas around us. This can be individual, family, peer and community.(30) Substance use may be familial, a person may have watched a parent or caretaker use alcohol on special occasions or more frequently. Perhaps you had a parent who smoked tobacco, and this may have played a role in whether you smoke. These social connections that are critical for our development as babies, toddlers, youth and into adulthood play a role in what we do, how we act, and how we live.

ACTIVITIES

- Brainstorm a list of things you do each day, from morning until night.

- Scratch out everything you do in a group. What is left?

- How much of your daily interactions are with a group?

- How did you learn to do each activity you do daily?

Social connections are also important for our health. Think back to the beginning days of the COVID-19 pandemic and how many people were negatively impacted by the social gathering restrictions. Some people used increased their substance use to cope with the isolation.(31) Some people used technology to connect with family, friends, and even with their workplace.

ACTIVITIES

- Brainstorm a list of things you did to cope with the isolation from the pandemic.

- Did you increase your substance use?

- How important is social connection in your life?

- Did technology help?

Social connection is an important factor in wellness and subsequently whether a person uses substances.(32)

Social Connection. By Every Mind Matters. Social contact is good for your mental health – even if you don’t always feel like engaging with other people when you’re low or anxious. This video will show you ways you can build more social connection into your life.

Transcript

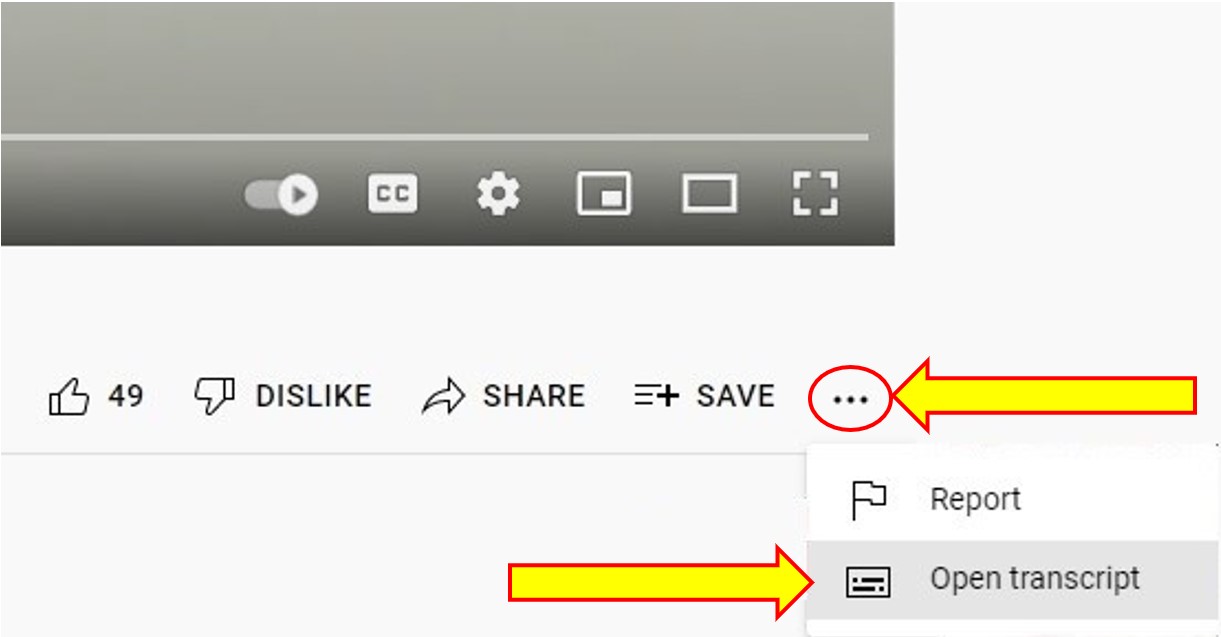

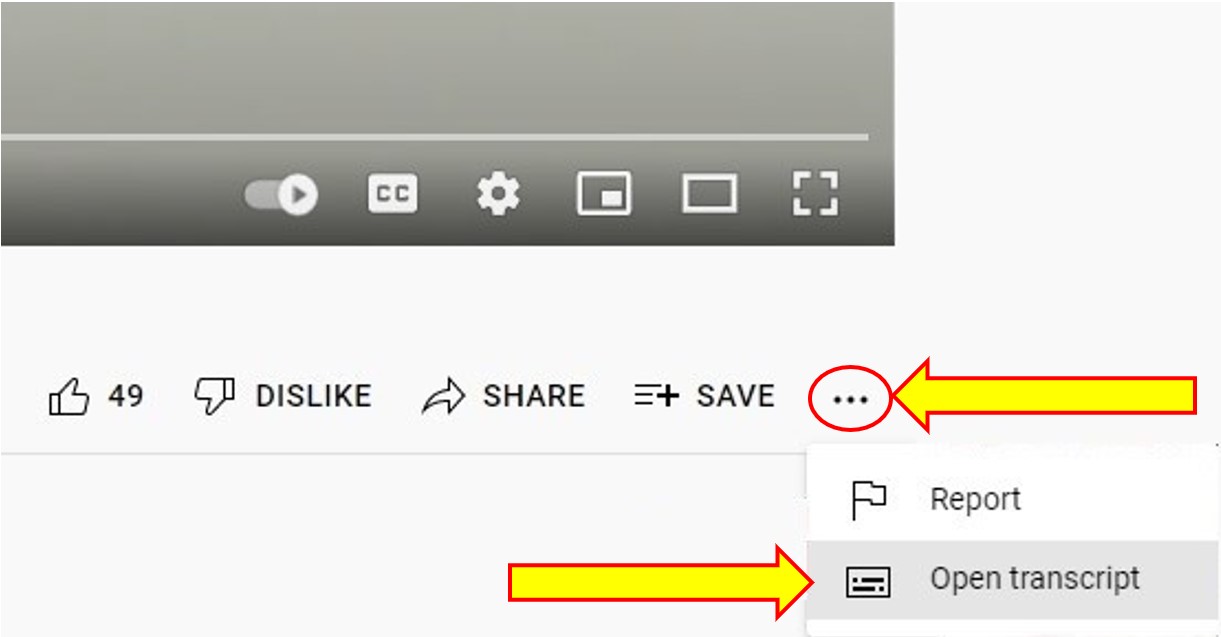

To Access the Video Transcript:

1. Click on “YouTube” on the bottom-right of the video. This will take you directly to the YouTube video.

2. Click on the More Actions icon (represented by three horizontal dots)

3. Click on “Open Transcript”

Social learning theory suggests behaviour is influenced by the interaction of personal, social, and environmental factors including intrapersonal factors, interpersonal factors, institutional or organizational factors, community factors, and public policy.(33) This is intersectionality. If you have been negatively impacted by one of these factors, are you susceptible to a substance use disorder? The research indicates yes; remembering it is one risk factor and does not mean it WILL lead to a substance use disorder. This theory is often used in counselling in supporting individuals with substance use disorders as it allows supporters to focus on individual, environmental, and societal factors.

Food For Thought

- Reflect on a happy memory from your childhood.

- Identify everyone who was involved.

- What were the factors that make this memory so wonderful?

The social factors that influence us are complex. Many of the treatment models use a social-ecological approach, identifying factors like trauma, adverse childhood experiences, mental health, racism, as well as self-efficacy.

FURTHER READING

Open Educational Resource Chapter 5 by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/substancemisusepart1/part/module-5-social-context-physical-environment-models-of-substance-misuse/

Attribution:

Exploring Substance Use in Canada by Julie Crouse is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

- Council on Social Work Education. (2021). Orientation to theories of substance use. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQdlvZc9leI&feature=emb_imp_woyt

- Csiernik, R. (2016) Substance use and abuse, everything matters, (p. 52). Canadian Scholars.

- Krentzman, A. R., Robinson, E. A., Moore, B. C., Kelly, J. F., Laudet, A. B., White, W. L., Zemore, S. E., Kurtz, E., & Strobbe, S. (2010). How Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) work: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2011.538318

- Al Ghaferi, H., Bond, C., & Matheson, C. (2016). Does the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of addiction apply in an Islamic context? A qualitative study of Jordanian addicts in treatment. Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 172(14), 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.019

- Miller, W. R. (1999). Conceptualizing motivation and change: Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64972/

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. (2018). The “God” word; agnostic and atheist members in A.A, (p. 5). AA Grapevine, Inc. https://www.aa.org/assets/en_US/p-86_theGodWord.pdf

- ALLCEU Counselling. (2012, July 18). Theories of addiction. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sf2HtrfwiQE&feature=emb_imp_woyt

- Wright, C. (2015). Consuming habits: Today’s subject of addiction. Subjectivity, 8, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2015.6

- Ibid, p. 97.

- Wright, C. (2015). Consuming habits: Today’s subject of addiction. Subjectivity, 8, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2015.6

- Ibid, p. 93.

- (n.d.). The moral model. https://www.youthaodtoolbox.org.au/sites/default/files/audio/No%20time%20to%20read%3F%20Listen%20instead%21%20The%20Moral%20Model.mp3

- Rundle, S. M., Cunningham, J. A. & Hendershot, C. S. (2021, January 25). Implications of addiction diagnosis and addiction beliefs for public stigma: A cross-national experimental study. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(5), 842-846. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13244

- McGinty E. E., & Barry C. L. (202, April 2). Stigma reduction to combat the addiction crisis –Developing an evidence base. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(14),1291-1292. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2000227

- FilmBilder & Friends. (2014, Oct. 13). Nuggets. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUngLgGRJpo

- Potenza M. N. (2013). Biological contributions to addictions in adolescents and adults: Prevention, treatment, and policy implications. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(2), 22-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3935152/

- Killing Pain. (2018, Aug. 29) The biology of addiction: Killing pain episode 2. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yMoL4i28hVw

- Soyka M., Kranzler, H. R., Hesselbrock, V., Kasper, S., Mutschler, J., Möller H. J., & The WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Substance Use Disorders. (2017). Guidelines for biological treatment of substance use and related disorders, part 1: Alcoholism, first revision. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 18(2), 86-119. https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=sWtwAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT8&dq=behavioural+theory+addiction&ots=Lv9CW4hdLO&sig=sEK–99BluIaVzBJsoGDadb9or8#v=onepage&q=behavioural%20theory%20addiction&f=false

- Rutherford, H. J., Mayes, L. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2010). Neurobiology of adolescent substance use disorders: implications for prevention and treatment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(3), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.003

- van Nimwegen, L., de Haan, L., van Beveren, N., van den Brink, W., & Linszen, D. (2005). Adolescence, schizophrenia and drug abuse: a window of vulnerability. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(s427), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00543.x

- Open Educational Resource. (n.d.). Theories of addiction: Causes and maintenance of addiction. Chapter 4. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/629967/mod_resource/content/1/addictionarticle1teeson.pdf

- Ibid.

- Potenza M. N. (2013). Biological contributions to addictions in adolescents and adults: Prevention, treatment, and policy implications. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(2), 22-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3935152/

- Teesson, M., Degenhardt, L., & Hall, W. (2002). Addictions. (chapter 4) East Sussex:UK. Psychology Press.

- Moos, R. H. (2007). Theory-based processes that promote the remission of substance use Disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(5), 537-551, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.006.

- Health Canada. (2021). How to quit smoking, (para. 6). https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/quit-smoking/how.html#a4

- Meyers, R. J., Roozen, H. G., & Smith, J. E. (2011). The community reinforcement approach: an update of the evidence. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 33(4), 380–388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860533/

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2017). Community reinforcement approach. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Community-Reinforcement-Approach-Summary-2017-en.pdf

- Jhanjee, S. (2014). Evidence based psychosocial interventions in substance use. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.130960

- Connell, C. M., Gilreath, T. D., Aklin, W. M., & Brex, R. A. (2010). Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance use among non-metropolitan high school students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(1-2), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9289-x para. 5

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021). COVID-19: Focus on substance use and stigma. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2021/05/covid-19-focus-on-substance-use-and-stigma.html

- Every Mind Matters. (2019). Social connection. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1EYcVpQeeE

- McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351-77. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F109019818801500401