4.3 Drugs and the Brain

Introducing the Human brain

The human brain is the most complex organ in the body. This three-pound mass of gray and white matter sits at the center of all human activity—you need it to drive a car, to enjoy a meal, to breathe, to create an artistic masterpiece, and to enjoy everyday activities. In brief, the brain regulates your body’s basic functions; enables you to interpret and respond to everything you experience; and shapes your thoughts, emotions, and behaviour.

The brain is made up of many parts that all work together as a team. Different parts of the brain are responsible for coordinating and performing specific functions. Drugs can alter important brain areas that are necessary for life-sustaining functions and can drive the compulsive drug abuse that marks addiction. Brain areas affected by drug abuse include:

- The brain stem, controls basic functions critical to life, such as heart rate, breathing, and sleeping.

- The cerebral cortex, is divided into areas that control specific functions. Different areas process information from our senses, enabling us to see, feel, hear, and taste. The front part of the cortex, the frontal cortex or forebrain, is the thinking center of the brain; it powers our ability to think, plan, solve problems, and make decisions.

- The limbic system, contains the brain’s reward circuit. It links together a number of brain structures that control and regulate our ability to feel pleasure. Feeling pleasure motivates us to repeat behaviours that are critical to our existence. The limbic system is activated by healthy, life-sustaining activities such as eating and socializing—but it is also activated by drugs of abuse. In addition, the limbic system is responsible for our perception of other emotions, both positive and negative, which explains the mood-altering properties of many drugs.

How do the parts of the brain communicate?

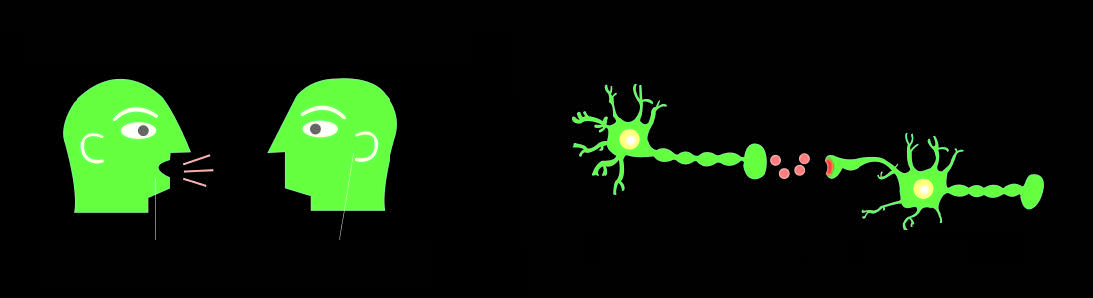

The brain is a communications center consisting of billions of neurons or nerve cells. Networks of neurons pass messages back and forth among different structures within the brain, the spinal cord, and nerves in the rest of the body (the peripheral nervous system). These nerve networks coordinate and regulate everything we feel, think, and do.

- Neuron to Neuron – Each nerve cell in the brain sends and receives messages in the form of electrical and chemical signals. Once a cell receives and processes a message, it sends it on to other neurons.

- Neurotransmitters—The Brain’s Chemical Messengers – The messages are typically carried between neurons by chemicals called neurotransmitters.

- Receptors: The Brain’s Chemical Receivers- “The neurotransmitter attaches to a specialized site on the receiving neuron called a receptor. A neurotransmitter and its receptor operate like a “key and lock,” an exquisitely specific mechanism that ensures that each receptor will forward the appropriate message only after interacting with the right kind of neurotransmitter.

- Transporters—The Brain’s Chemical Recyclers – Located on the neuron that releases the neurotransmitter, transporters recycle these neurotransmitters (that is, bring them back into the neuron that released them), thereby shutting off the signal between neurons.

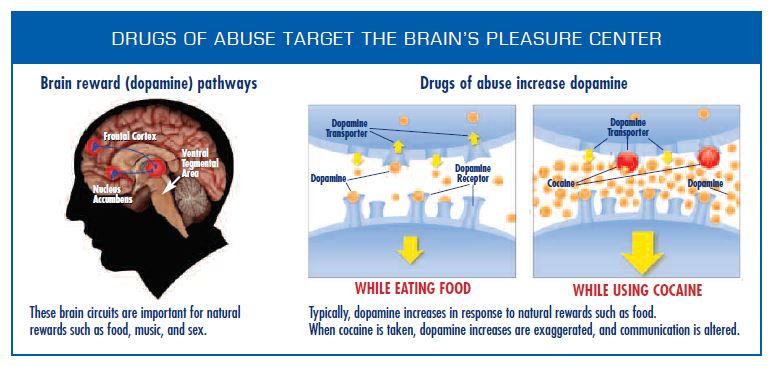

Most drugs of abuse target the brain’s reward system by flooding it with dopamine.

How do drugs work in the brain?

Drugs are chemicals that affect the brain by tapping into its communication system and interfering with the way neurons normally send, receive, and process information. Some drugs, such as marijuana and heroin, can activate neurons because their chemical structure mimics that of a natural neurotransmitter. This similarity in structure “fools” receptors and allows the drugs to attach onto and activate the neurons. Although these drugs mimic the brain’s own chemicals, they don’t activate neurons in the same way as a natural neurotransmitter, and they lead to abnormal messages being transmitted through the network. Other drugs, such as amphetamine or cocaine, can cause the neurons to release abnormally large amounts of natural neurotransmitters or prevent the normal recycling of these brain chemicals. This disruption produces a greatly amplified message, ultimately disrupting communication channels.

How do drugs work in the brain to produce pleasure?

Most drugs of abuse directly or indirectly target the brain’s reward system by flooding the circuit with dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, motivation, and feelings of pleasure. When activated at normal levels, this system rewards our natural behaviours. Overstimulating the system with drugs, however, produces euphoric effects, which strongly reinforce the behaviour of drug use—teaching the user to repeat it.

How does stimulation of the brain’s pleasure circuit teach us to keep taking drugs?

Our brains are wired to ensure that we will repeat life-sustaining activities by associating those activities with pleasure or reward. Whenever this reward circuit is activated, the brain notes that something important is happening that needs to be remembered and teaches us to do it again and again without thinking about it. Because drugs of abuse stimulate the same circuit, we learn to abuse drugs in the same way.

Why are drugs more addictive than natural rewards?

When some drugs of abuse are taken, they can release 2 to 10 times the amount of dopamine that natural rewards such as eating and sex do.15 In some cases, this occurs almost immediately (as when drugs are smoked or injected), and the effects can last much longer than those produced by natural rewards. The resulting effects on the brain’s pleasure circuit dwarf those produced by naturally rewarding behaviours. 16,17 The effect of such a powerful reward strongly motivates people to take drugs again and again. This is why scientists sometimes say that drug abuse is something we learn to do very, very well.

Long-term drug abuse impairs brain functioning.

What happens to your brain if you keep taking drugs?

For the brain, the difference between normal rewards and drug rewards can be described as the difference between someone whispering into your ear and someone shouting into a microphone. Just as we turn down the volume on a radio that is too loud, the brain adjusts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine (and other neurotransmitters) by producing less dopamine or by reducing the number of receptors that can receive signals. As a result, dopamine’s impact on the reward circuit of the brain of someone who abuses drugs can become abnormally low, and that person’s ability to experience any pleasure is reduced.

This is why a person who abuses drugs eventually feels flat, lifeless, depressed, and is unable to enjoy things that were previously pleasurable. Now, the person needs to keep taking drugs again and again just to try and bring his or her dopamine function back up to normal—which only makes the problem worse, like a vicious cycle. Also, the person will often need to take larger amounts of the drug to produce the familiar dopamine high—an effect known as tolerance.

How does long-term drug taking affect brain circuits?

We know that the same sort of mechanisms involved in the development of tolerance can eventually lead to profound changes in neurons and brain circuits, with the potential to severely compromise the long-term health of the brain. For example, glutamate is another neurotransmitter that influences the reward circuit and the ability to learn. When the optimal concentration of glutamate is altered by drug abuse, the brain attempts to compensate for this change, which can cause impairment in cognitive function. Similarly, long-term drug abuse can trigger adaptations inhabit or non-conscious memory systems. Conditioning is one example of this type of learning, in which cues in a person’s daily routine or environment become associated with the drug experience and can trigger uncontrollable cravings whenever the person is exposed to these cues, even if the drug itself is not available. This learned “reflex” is extremely durable and can affect a person who once used drugs even after many years of abstinence.

What other brain changes occur with drug abuse?

Chronic exposure to drugs of abuse disrupts the way critical brain structures interact to control and inhibit behaviours related to drug use. Just as continued abuse may lead to tolerance or the need for higher drug dosages to produce an effect, it may also lead to addiction, which can drive a user to seek out and take drugs compulsively. Drug addiction erodes a person’s self-control and ability to make sound decisions while producing intense impulses to take drugs.

Long Descriptions

Figure 4.3.1 – To send a message, a brain cell (neuron) releases a chemical (neurotransmitter) into the space (synapse) between it and the next cell. Concept courtesy of: B.K. Madras. The neurotransmitter crosses the synapse and attaches to proteins (receptors) on the receiving brain cell. This causes changes in the receiving cell—the message Transmitter Receptor Neurotransmitter Receptor is delivered.

References

Figure 4.3.1 – Madras, B. K. (2014). Neurotransmitters [Photo]. NIH: National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/soa_2014.pdf. These are public domain images

Figure 4.3.2 – (2014). Neurotransmitters [Photo]. NIH: National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/soa_2014.pdf. These are public domain images