7.3 Drug Policy and the War on Drugs

We will start this module with a short video from the Municipal Alcohol Project and the Nova Scotia Community College.

Municipal Alcohol Project PSA. by Key Studios. An underage drinking awareness public service announcement created in partnership between Nova Scotia Community College Truro Campus and Mental Health and Addiction Services.(1)

Transcript

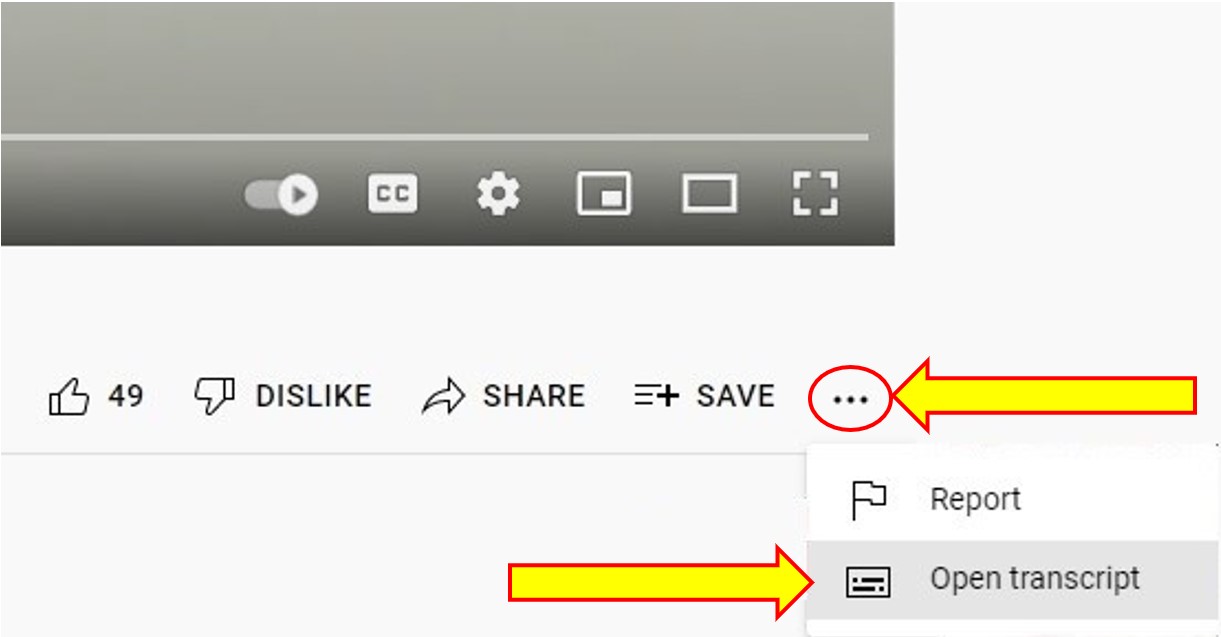

To Access the Video Transcript:

1. Click on “YouTube” on the bottom-right of the video. This will take you directly to the YouTube video.

2. Click on the More Actions icon (represented by three horizontal dots)

3. Click on “Open Transcript”

Videos like this suggest abstinence is best; however, abstinence does not work for everyone. Abstinence-based programs and policies are not evidence-based, and yet are still being used to address substance use and substance use disorders. They are the remnants of the “war on drugs,” which began in the Reagan era (1981-1989) of the United States and were generally seen as failed policy (2). The term “war on drugs” began with Ronald Reagan, the President of the United States in 1984. His wife Nancy began a popular, yet ineffective campaign, “Just Say No”. This campaign was based on abstinence and spawned other abstinence-based programs like DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education)(3).

Many people believe the war on drugs was an American phenomenon; however, Canada was a willing ally and created laws that targeted marginalized groups(4). In the 1980s, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney invested in Canada’s war on drugs based on the false belief that communities were being ravaged by drugs, though evidence on use suggested otherwise(5). The war on drugs has been a worldwide phenomenon that resulted in the criminalization and incarceration of people who use substances; “historically, the principal response to illegal drug use has been enforcement and incarceration”(6).

The war on drugs was not successful, yet it continues to have impacts on Canada’s laws, correctional facilities, RCMP and Police, healthcare, and economy. Data from Canada and elsewhere show “this approach fails to meaningfully reduce the supply of – or demand for – drugs and results in many unintended negative consequences”(7); for example, “overdose is a leading cause of premature mortality in North America”(8). Consequences of the war on drugs also include incarceration and the myriad of challenges associated with having a criminal record. Yet Canada and other countries have continued to engage in a political war on drugs though according to Mallea(9), “it has not reduced the drug trade, eliminated production, or decreased the number of users”(10). Gordon (11) suggests the criminalization of substances and people who use substances has not occurred in a vacuum; it has been a “state policy that intersects profoundly with the racialized class relations of Canadian capitalist society” (12).

Robyn Maynard – Policing Black Lives. By Fernwood Publishing. Author Robyn Maynard speaks about her book, Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present, available in stores and online: https://fernwoodpublishing.ca/book/po… (13)

The transcript for this event can be found here: https://bit.ly/3d65F7b

This racialized focus in the war on drugs has resulted in an over-representation of incarceration for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities. “Racialization strengthens systemic racism and reinforces structural violence” (14). To understand how racialization has played a role in Canada’s war on drugs one must simply look to the correctional system. For example, 80% of people who have been incarcerated have substance use disorders (15) and 54% of offenders were under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs at the time of the offence for which they were currently serving a sentence (16). If we look at the correctional system we can see in 2016, Indigenous Canadians accounted for 24.4% of the federal prison population, though they make up just 4.3% of the general population (17). In 2010–2011, Black Canadians accounted for 10% of the federal prison population although Black Canadians only comprised 2.5% of the overall population (18). We are incarcerating people for their substance use and this racialization of the war on drugs has resulted in blackness associated with criminality (19).

The war on drugs has been a catastrophic failure that has directly impacted BIPOC communities and indirectly impacted all Canadians; “war always destroys lives, produces a maximum of collateral damage, denies basic human and civil rights, and has little to do with justice” (20). Many advocates who work in the field of substance use disorders believe it is time to end the war on drugs and focus efforts on the intersectionality of the systemic issues that perpetuate substance use disorders (21).

Angel Gates: Insight from community on the devastating toll of Canada’s drug policies. by Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. At the heart of Canada’s overdose crisis are people with lived and living experience with substance use who have the clearest understanding of the systemic flaws inherent in our drug policies, along with the devastating human toll wrought by them. Their insight must guide and inform new policies if they are to have any positive impact on the lived realities of communities most deeply affected. They are the “experts to the experts,” and their contributions must be privileged for policies to succeed.

Transcript

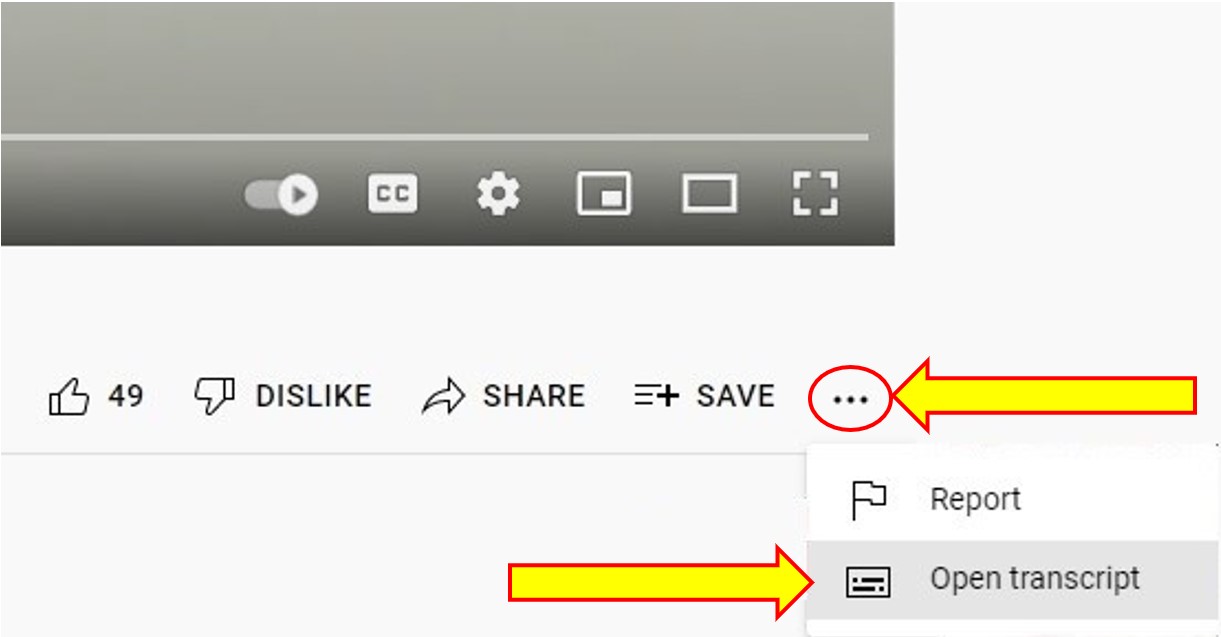

To Access the Video Transcript:

1. Click on “YouTube” on the bottom-right of the video. This will take you directly to the YouTube video.

2. Click on the More Actions icon (represented by three horizontal dots)

3. Click on “Open Transcript”

Food for Thought

- How do we determine if a law or policy does more harm than good?

- According to Husak (21), all substance use should be allowed in a free society. Agree or disagree? Why?

- If you think some substances should stay illicit, what are they? Why?

- How might access to all substances change how people use substances? Why? Can you relate this to a theory?

In deepening your understanding of the “war on drugs” please review the infographic below for the impact on Canadians. Drug War in Canada by Canadian Centre for Addictions

Image Credit

Nancy Reagan Speaking at a “Just Say No” Rally in Los Angeles California. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution:

This Chapter is an adaptation of Exploring Substance Use in Canada by Julie Crouse is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

- Key Studios. (2014, Feb. 26). Municipal alcohol project PSA. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcH71oiOd48

- Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Spittal, P. M., Li, K., Anis, A. H., Hogg, R. S., Montaner, J. S. G., O’Shaughnessy, M. V. O., & Schechter, M. T. (2003). Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: Investigation of a massive heroin seizure. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(2), 165-169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12538544/

- Key Studios. (2014, Feb. 26). Municipal alcohol project PSA. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcH71oiOd48

- Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Spittal, P. M., Li, K., Anis, A. H., Hogg, R. S., Montaner, J. S. G., O’Shaughnessy, M. V. O., & Schechter, M. T. (2003). Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: Investigation of a massive heroin seizure. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(2), 165-169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12538544/

- Drug Policy Alliance. (2021). A history of the drug war. https://drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war

- Ibid.

- Maynard, R. (2017). Policing black lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present. Fernwood Publishing.

- Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Spittal, P. M., Li, K., Anis, A. H., Hogg, R. S., Montaner, J. S. G., O’Shaughnessy, M. V. O., & Schechter, M. T. (2003). Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: Investigation of a massive heroin seizure. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(2), 165-169. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12538544/

- Ibid.

- Marshall, B. D., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: A retrospective population-based study. The Lancet, 377(9775), 1429-37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21497898/

- Mallea, P. (2014). The war on drugs: A failed experiment. Dundurn Press.

- Ibid, p. 11

- Fernwood Publishing. (2017, October 10). Robyn Maynard – Policing Black Lives [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-JpQjhVvlM

- Khenti, A. (2014) The Canadian war on drugs: Structural violence and unequal treatment of Black Canadians. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 190–195. https://health.gradstudies.yorku.ca/files/2016/09/The-Canadian-war-on-drugs-Structural-violence-and-unequal-treatment-of-Blacks.pdf

- Motiuk, L., Boe, R., & Nafekh, M. (2003). The safe return of offenders to the community. Correctional Service Canada. https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/sr2005-eng.shtml

- Pernanen, K., Cousineau, M.M., Brochu, S. & Fu, S. Proportions of crimes associated with alcohol and other drugs in Canada. Report for the Canadian Centre on Substance Use. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/ccsa-009105-2002.pdf

- Government of Canada. (2019). Department of Justice – Spotlight on Gladue: Challenges, experiences, and possibilities in Canada’s criminal justice system. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/gladue/p2.html

- Wortley, S., & Owusu-Bempah, A. (2011). The usual suspects: Police stop and search practices in Canada. Policing and Society, 21(4), 395–407. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238046161_The_Usual_Suspects_Police_Stop_and_Search_Practices_in_Canada.

- Khenti, A. (2014) The Canadian war on drugs: Structural violence and unequal treatment of Black Canadians. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 190–195. https://health.gradstudies.yorku.ca/files/2016/09/The-Canadian-war-on-drugs-Structural-violence-and-unequal-treatment-of-Blacks.pdf

- Nusbaumer, M. R. (2009). Hooked: Drug war films in Britain, Canada and the United States. Contemporary Justice Review, 12(3), 367-369. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580903105921

- Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. (2020, Oct. 5). Angel Gates: Insight from community on the devastating toll of Canada’s drug policies. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiWcXFvWdIc

- Husak, D. N. (2002). Legalize this! The case for criminalizing drugs. Verso Publishing

- Drug War in Canada infographic from: Canadian Centre for Addictions. (2021). Canada’s shocking war on drugs: An infographic. https://canadiancentreforaddictions.org/war-on-drugs/