9.7 Current Overdose Prevention Programs

In this chapter we examine a variety of Overdose Prevention Programs.

Overdose Prevention Programs Learning Objectives

- What is Overdose Prevention

- Explain what increases the risk of an opiate overdose

- Discuss how communities can help prevent overdose

- Know where you would go for naloxone in your community

- Explain what some of the strategies are for Overdose Prevention

- Discuss the difference between a supervised consumption/supervised injection site (SIS) and an overdose prevention site (OPS)

End the Stigma. By Healthy Canadians. Stigma is making it harder for people to get help. Transcript: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canad…(1)

Transcript

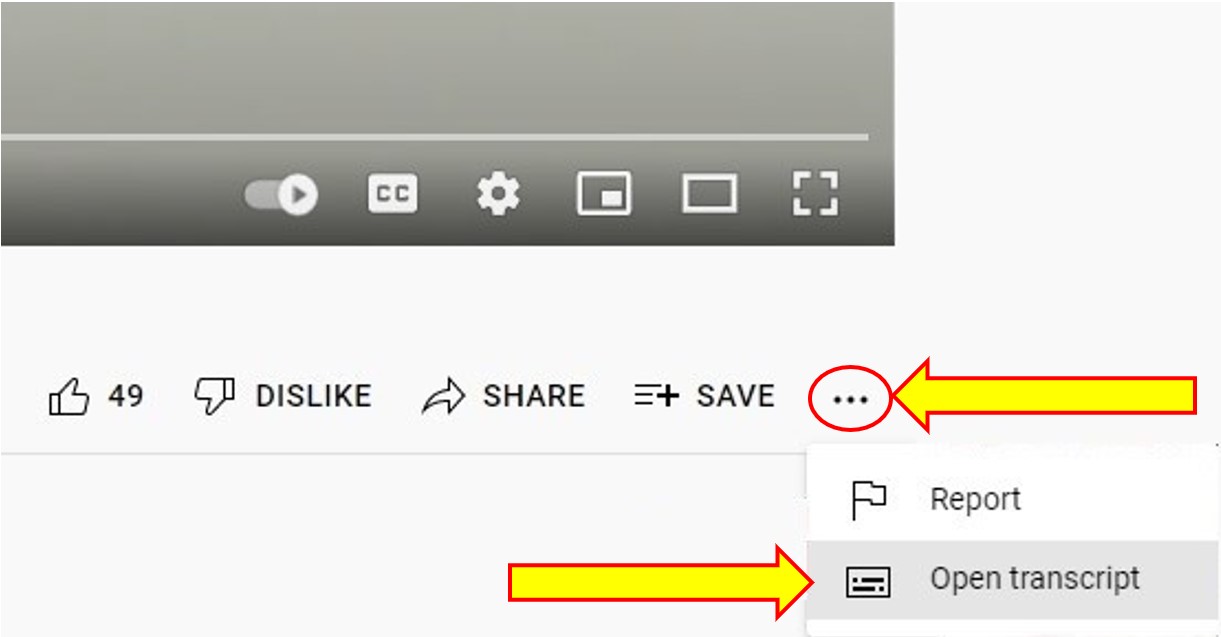

To Access the Video Transcript:

1. Click on “YouTube” on the bottom-right of the video. This will take you directly to the YouTube video.

2. Click on the More Actions icon (represented by three horizontal dots)

3. Click on “Open Transcript”

As part of Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response in Canada – Canadian Drug Policy Coalition(2) has had to develop comprehensive strategies to prevent the number of overdose deaths. This is a critical nature of the opioid crisis in both Canada and North America.

Globally, overdose has become the leading preventable cause of death among people who inject drugs. By offering simple program and policy changes, it will prevent many unintentional deaths and injury from opioid overdoses.

It is important to have a comprehensive public health approach to reduce harm reduction both globally and in Canada. Using strategies that do not require stopping using drugs, but instead allowing them to participate in harm reduction with their drug use, it allows them to identify and get strategies, solutions and support for their health and safety needs, which has a huge impact on economic implications as well in Canada.

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition at Simon Fraser University has created five key components.

- Make naloxone kits readily available to everyone and as cost effective as possible with minimum barriers. The Canadian government has implemented free naloxone kits that anyone can get from a pharmacy upon request.

- Engage communities with education and training on how to use naloxone kits including families, using peers and health care workers.

- Good Samaritan Legislation (Good Samaritan Act) that would allow and encourage someone to call 911 in case of overdose without fear of legal reprisal.

- Create better guidelines to prescribe opiates for the management of pain and ensure there is no discrimination against people who use drugs.

- Track overdose events and provide data publicly to help awareness in the using population. (2)

Overdose Prevention Sites (OPS)

What is the difference between a supervised consumption/supervised injection site and an overdose prevention site (OPS)? An overdose prevention is less formalized than SCS (Supervised Consumption Sites) / SIS (Supervised Injections Site). Anecdotal evidence suggests OPS are lower barrier than supervised consumption/supervised injection site and offer the expertise and direct experience of experiential peer workers, filling a much needed service in the tapestry of harm reduction (Pivot Legal Society, 2020)(4).

Overdose Prevention Sites (OPSs) developed in a similar way as supervised injection sites, from grassroots activism by people who use substances pushing the agenda. Many different agencies across Canada helped create “pop-up” unsanctioned sites in a few locations in BC Health Impacts on a scaled-up of SIS Injection Services in a Canadian Setting (BC)(4) In 2017, Health Canada announced a new strategy to address the opioid crisis with the exemptions of OPS’s. The OPS applies for an exemption under Health Canada, then applies to the province for a three to six month exemption under the Controlled Drug & Substances Act.

The OPS can address an “at-risk” community (an area where there is high substance use and overdose death) by providing space (sometimes a tent, sometimes a store front location) for people to consume their substance of choice (including inhalation) with sterile equipment, in settings where they can be observed, and others can quickly intervene in the event of an overdose.

They are generally staffed by peers and harm reduction workers. OPS are not required to have health care professionals on staff and are considered “pop-up” as they are a mobile response to overdose prevention. There are many challenges for these types of programs, which are individual depending on what area, city, province/territory they are in.

For More Information on Supervised Consumption /Overdose Prevention Sites:

This map shows supervised consumption sites (SCS) across the country and overdose prevention sites (OPS) in BC. Click on the icon for information about each site. Click the button in the top righthand corner of the map to view a larger map.

- Canada’s Supervised Consumption and Overdose Prevention Sites

- Street Health in Toronto (OPS)

- List of SCS & OPS in Canada

- SisterSpace: Canada’s first and only overdose prevention site for women is saving lives

- Overdose Prevention Sites – Addictions and Mental Health Ontario Conference

- Alberta in talks to open OPS – CBC news – March 2022

More Information on Overdose Prevention Programs in Canada

- St. Paul’s Hospital’s overdose prevention site marks its first year – BC

- Atlantic Canada’s 1st overdose prevention site opens in Halifax – Global News

- N.S. to find two overdose prevention sites – Global News

- VIDEO: An inside look at Nelson’s overdose prevention site (BC)

- Alberta in talks to open overdose prevention sites – CBC

- Timmins Ontario Overdose – CTV

- StreetHealth in Toronto Overdose Prevention Site (OPS)

- CATIE Supervised consumption services/Overdose prevention sites

What’s the difference between an SCS and an OPS?

Supervised consumption sites (SCS) and overdose prevention sites (OPS) share many features, but they are legally and practically very distinct.

SCS are facilities that have been exempted by Health Canada under section 56.1 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.(5) Inside an SCS, people can use their own illicit drugs (and staff can witness them) without being prosecuted for drug possession. In addition to witnessed injection and emergency overdose response, SCS typically offer a range of other support services to clients, including referrals to treatment programs and access to housing supports. Procedurally, establishing a SCS is laborious and time-consuming: It can take several years get an approval, since the exemption application must include information about the site’s policies and procedures, personnel, financial plan, local conditions, and community consultation. Though SCS afford a degree of stability and longevity, operators must still apply to extend an exemption periodically (usually annually).

OPS were established as a community-based response to overdose deaths and the sluggish bureaucracy associated with SCS applications. OPS tend to be peer-run, barer-bones facilities (sometimes consisting of a tent in a public park) where people can use their own illicit drugs, access sterile harm reduction equipment, and receive emergency overdose response as needed. Many people prefer OPS to SCS, and OPS fill a critical gap in the spectrum of harm reduction: OPS are lower-barrier than SCS and offer the expertise and direct experience of experiential “peer” workers. Oftentimes, they allow modes of consumption that are prohibited in most SCS, such as drug inhalation. Unlike SCS, OPS do not require an exemption from Health Canada. They began as “pop up” sites led by people who use drugs.

Now in BC, they usually run via an Overdose Prevention Services – BC(6) from the Minister of Health, which requires Emergency Health Services and the Health Authorities to ensure OPS are available throughout the Province. However, in some other Provinces (i.e. Ontario), OPS run via a temporary, Province-wide exemption from the federal government. OPS are nimble and can be set up quickly to respond to the immediate needs of people who use drugs. Despite the huge success of OPS in saving lives (and the existence of a Ministerial Order), many municipalities and Health Authorities have failed in their responsibilities and remain hostile to folks who courageously set up OPS in their communities.

Read CAPUD’s important guide to setting up an OPS(7)

We owe the existence of SCS and OPS to the direct action of people who use drugs. Long before Insite(8) became the first sanctioned SCS in North America, people who use drugs were running their own injection rooms and needle exchanges to save lives in the face of government inaction and the War on Drugs. As is always the case, folks had to save their own lives first, at tremendous personal risk, before government came around to the idea of supervised injection. In Canada, the provision of OPS is sorely inadequate, and people who use drugs continue to shoulder the burden of saving lives as municipalities and health authorities stand by idly and, at times, with hostility. SCS and OPS save lives: no one has ever died at either type of facility.

Naloxone

To prevent overdose deaths, having a comprehensive harm reduction strategy, is important. The Canadian Pharmacist Association has created a site where you can go to find access to Naloxone across Canada. This is to ensure individuals and communities have access to naloxone, an opioid antagonist to an opioid overdose.

Access to Naloxone across Canada

Food For Thought

- Why would some pilot projects on substance use disorders do not get funded?

- What is the role of media in sharing information?

- What is the role of activism/advocacy?

Naloxone kits are just one component; helping individuals understand the risks of using a substance alone is another arm of naloxone.

There are many forms of harm reduction and many harm reduction programs in Canada. Harm reduction is an important pillar in healthcare for people who use substances

Incarcerated Good Samaritan Act

The Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act provides some legal protection for individuals who seek emergency help during an overdose.

The Act became law on May 4, 2017. It complements the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy,(10) our comprehensive public health approach to substance use. Harm reduction is a key part of the strategy alongside prevention, treatment, and enforcement.

We hope the Act will help to reduce fear of police attending overdose events and encourage people to help save a life.

Call, stay and help. By Healthy Canadians. The Good Samaritan law can protect you from simple drug possession charges. Transcript: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canad… (11)

Suspect an Overdose?

- Stay and Call 911 or your local emergency number

- The Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act can protect you from simple drug possession charges.

- Learn more at Canada.ca/Opioids

- Together we can #StopOverdoses

For more information:

Chapter Attribution:

This chapter is not covered by the adaptation statement (original)

References

- Healthy Canadians. (2021, February 16). End the stigma [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inDI06DXVjg

- Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. (2016, November 8). Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response in Canada – Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. https://drugpolicy.ca/about/publication/opioid-overdose-prevention-and-response-in-canada/

- Health Canada. (2021b, November 23). About the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/opioids/about-good-samaritan-drug-overdose-act.htm

- Health Impacts on a scaled-up of SIS Injection Services in a Canadian Setting (BC), https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Kennedy-et-al.-Health-impacts-of-a-scale-up-of-supervised-injection-services-in-a-Canadian-setting-Proofs.pdf

- Legislative Services Branch. (2023b, January 14). Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-38.8/page-1.html

- Canada’s Supervised Consumption and Overdose Prevention Sites. (n.d.). Pivot Legal Society. https://www.pivotlegal.org/scs_ops_map

- CAPUD. (n.d.). CAPUD (Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs. https://www.capud.ca/

- PHS Community Services Society. (2022, January 21). Insite | PHS Community Services Society. PHS. https://www.phs.ca/program/insite/

- Health Impacts on a scaled-up of SIS Injection Services in a Canadian Setting (BC), https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Kennedy-et-al.-Health-impacts-of-a-scale-up-of-supervised-injection-services-in-a-Canadian-setting-Proofs.pdf

- Legislative Services Branch. (2023b, January 14). Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-38.8/page-1.htmlHealthy Canadians. (2021a, February 16). Call, stay and help [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e1l4OHLQ4jg

- Government of Canada. (2021b, November 23). Good Samaritan Act. Retrieved March 30, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/opioids/about-good-samaritan-drug-overdose-act.html