12 A Case Study of Gymnastics Canada’s Safe Sport Framework

Ellen MacPherson

Ian Moss

Themes

Program development and delivery

Stakeholder engagement

National level sport

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

LO1 Identify the steps used by a national sport organization to conceptualize, develop, and deliver a Safe Sport program;

LO2 Identify the stakeholders involved in developing a comprehensive Safe Sport program and describe examples of each stakeholder’s role and responsibilities;

LO3 Identify examples of GymCan’s knowledge mobilization activities, wherein up-to-date research is translated to practice; and

LO4 Describe potential challenges associated with the design and delivery of Safe Sport.

Overview

In early 2018, in response to the international movement to shift the culture of sport, Gymnastics Canada (GymCan) became one of the first National Sport Organizations (NSOs) in Canada to hire a full-time Director, Safe Sport. The core focus of the Director, Safe Sport’s portfolio is to develop, implement, and evaluate organizational initiatives that create and promote safe, healthy, and inclusive experiences for all individuals in the sport. A cornerstone of GymCan’s Safe Sport portfolio is the Safe Sport Framework, which serves as the guiding strategic plan for the organization’s Safe Sport program and includes GymCan’s definition and vision of “safe sport”, organizational principles for safe gymnastics environments, the broad topics comprising the program, and the corresponding policy, education, and advocacy initiatives required to promote positive, healthy, and safe practices.

This chapter provides an overview of the process of developing GymCan’s Safe Sport Framework, discusses design and implementation of a few key safe sport policy, education, and advocacy initiatives, reviews some of the challenges encountered and lessons learned along the way, suggests critical areas of focus to enhance impact (e.g., athlete’s voice, shared responsibility and collaboration, evidence-based programming), and provides sample activities, learning modules, podcasts, and other resources to bolster students’ and industry professionals’ safe sport toolkits.

Key Dates

Overview of Gymnastics and the Canadian Sport’s Eight Recognized Disciplines

The International Gymnastics Federation (FIG) is considered the governing body for the sport of gymnastics worldwide and remains the oldest established international federation for sport in the Olympic era.[1] While the FIG sets the international regulations for gymnastics, each member federation (i.e., Gymnastics Canada) is responsible for developing the operating rules, regulations and policies, as well as overall sport experience at the national level.[2] As a result, national governing bodies typically set the overarching values, standards, safety regulations, education, and development for individuals in their programs.[3]

In consideration of the position of an NSO in the overarching sport structure, this chapter explores the role of Gymnastics Canada in developing, supporting, and fostering safe sport, including a general overview of the sport of gymnastics, the unique challenges of the sport, the organizational structure of GymCan, the factors influencing the development of a dedicated safe sport portfolio, steps to developing a Safe Sport Framework and considerations for future program development.

The sport of gymnastics has eight different disciplines, with each discipline possessing distinct technical rules, regulations, eligibility requirements and artistic elements.[4] The gymnastics disciplines include: women’s and men’s artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, trampoline and tumbling, acrobatic gymnastics, aerobic gymnastics, parkour, and Gymnastics for All. Each of the disciplines will be briefly explained below.

Figure 12.1 Disciplines of Gymnastics

Unique Challenges of the Sport of Gymnastics

In general, gymnastics presents a few unique challenges with respect to the development and effective implementation of Safe Sport parameters across the sport. GymCan works collaboratively with its Provincial/Territorial sport organizations to mitigate and manage these ongoing challenges.

Examples of these challenges include but are not limited to:

- Culture:

Anecdotally, each gymnastics discipline has a distinct culture, including a unique origin story, worldwide influences, safe sport vulnerabilities, gaps and considerations, technical structure, rules, regulations, and program requirements. As a result, challenges may arise when designing, delivering, and implementing standardized policy, procedures, and education initiatives for safe sport. Therefore, it is critical for professionals working in the sport of gymnastics (or the Canadian Sport System, more generally) to allocate appropriate time to familiarizing oneself with the existing culture(s) and subsequent challenges within a given sport in order to develop, implement and evaluate safe sport initiatives.

- Age of athletes:

In general, gymnastics tends to be considered an early specialization sport, which means that young athletes are often encouraged to invest significant time and energy into the sport from an early age, while limiting participation in other sports.[5] Though actively debated in academic literature and practice, proponents of early specialization suggest that deliberate practice (i.e., higher training volume) from a young age increases the likelihood of elite performance.[6] Given the tendency for gymnastics to fall into this category, it is important for Safe Sport professionals to consider the unique risks associated with younger athletes, including vulnerability to power dynamics, travel, physical size, overuse injuries, level of awareness of maltreatment and other factors (Brackenridge, 1997). Further, as one of the organization’s key Safe Sport advocates, it is imperative to consistently ensure holistic well-being is at the forefront of all conversations, decisions, and programming.

- Physical Safety Risks:

In addition to the safety vulnerabilities posed above, there are also several general safety risks inherent to the sport of gymnastics that may result in a wide array of injuries, including but not limited to[7]- Improper use of equipment;

- Mechanical issues with equipment;

- Dynamic, complex, and fast-paced nature of skills;

- Developmental age and stage of athletes; and

- Demanding and strenuous physical skills.

- Professionalization of Coaching:

The sport of gymnastics in Canada is largely programmed through established local gymnastics clubs that operate within two primary business models: not-for-profit (volunteer board managed with professional staff) and for-profit (private businesses with limited volunteer oversight). In each of these models, professional staff (and particularly coaches) figure prominently in the delivery of services and programs. While Canada is well-served by the National Coaching Certification Program (NCCP) for technical training of coaches, it has only recently begun to address the parameters of Safe Sport in its general curriculum and education strategy. As a result, NSOs are currently responsible for creating extensive educational programming to address expectations of conduct and help coaches specifically, adapt and develop their practice in an evolving environment. In addition, gymnastics coaches do not have an external self-regulating or policing professional coaching organization and therefore rely on national, provincial and local club safe sport policies and mechanisms for enforcement.

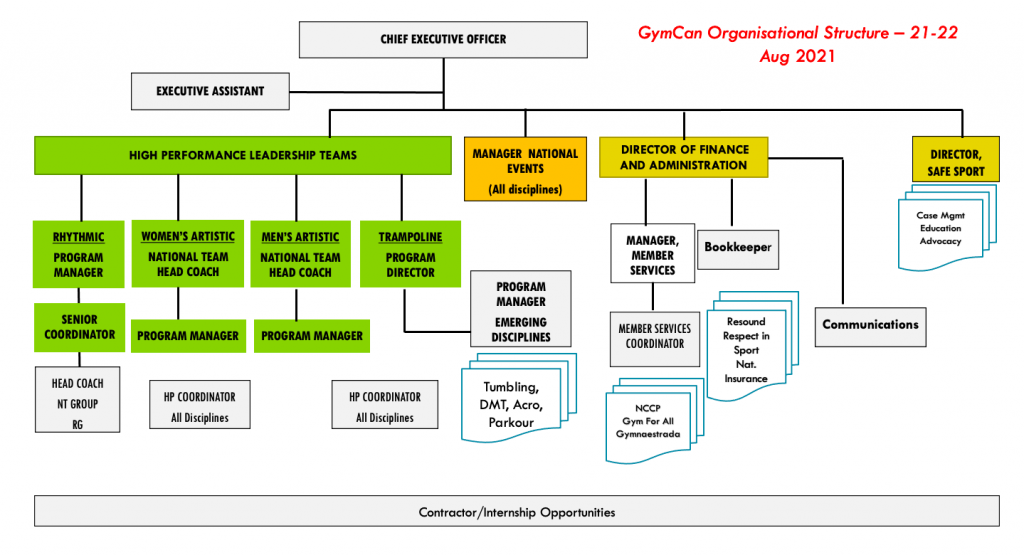

Role of the National Sport Organization in Design and Delivery of Sport

To illustrate the role of the GymCan in the design and delivery of gymnastics programming in Canada, please refer to Figure 12.2, which illustrates GymCan’s organizational chart and lists the areas of operation and roles within each program. In addition, please refer to GymCan’s 2021-2026 strategic plan to review the vision, mission, values and future direction of the organization.

Figure 12.2 GymCan Organisational Structure

Figure 12.3 Gymnastics Canada Vision, Mission, Overarching Goals, and Values

“Gymnastics Canada: From Here, We Soar” celebrates the role of GymCan in supporting the mastery of movement in Canada for the past five decades.

Creating a Safe Sport Program at Gymnastics Canada

Although GymCan and its provincial organizations implemented some initiatives considered under the umbrella of “safe sport” in past, including Respect in Sport training, there was not a stand-alone portfolio developed to support the conceptualization, delivery and evaluation of safe sport initiatives until 2018. The following section will briefly identify some of the factors that led to the creation of a dedicated safe sport portfolio, including:

- The case of United States Gymnastics’ (USAG) team doctor Larry Nassar;

- High-profile cases in Canadian Sport;

- The global #MeToo Movement; and

- GymCan’s own community’s call for a system-wide culture shift to more positive, healthy, and inclusive sport environments.

1. The Case of United States Gymnastics’ (USAG) Team Doctor Larry Nassar

Dr. Larry Nassar began working with the United States gymnastics team in 1986 and continued providing medical care until 2015, shortly before he was accused of sexually assaulting more than three hundred people with whom he interacted, primarily through his medical practices at Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics (USAG).[8] Nassar pleaded guilty to the criminal charges against him and received a sentencing of sixty years in prison.[9] At the trial, over 150 women – many of whom were female athletes – shared testimonies of the abuse carried out by Nassar.[10]

The case of Larry Nassar and USAG has since been the subject of a Netflix documentary titled “Athlete A” and sparked current and former athletes worldwide to speak out about their experiences with maltreatment in gymnastics under the social media hashtag #GymnastAlliance.[11] In addition, many of the survivors in this case continue to share their experiences, including the lasting harmful effects of the abuse in different realms (e.g., social media, federal government hearings, traditional media)[12] to advocate, call for change, and prevent maltreatment from occurring in the future.

2. High Profile Cases in Canadian Sport

Safe Sport issues have not been immune to the Canadian context, with high-profile maltreatment cases occurring across all sports for many years, including, gymnastics, athletics, alpine, hockey, and swimming, among others. In a recent study by Willson, Kerr, Stirling, and Buono,[13] the authors surveyed 1001 current or former Canadian national team winter and summer sport athletes and revealed: 76% of retired athletes and 67% of current athletes reported experiencing at least one neglectful behaviour; 62% of retired athletes and 59% of current athletes reported experiencing at least one psychologically harmful behaviour; 21% of retired athletes and 20% of current athletes reported at least one sexually harmful behaviour; and, 19% of retired athletes and 12% of current athletes reported at least one physically harmful behaviour (for more information about safe sport from an athlete perspective, please see Chapter 2). While the present study focused exclusively on national team level athletes, anecdotal evidence across sport suggests that safe sport issues transcend national teams to reach all levels of sport.

To encourage reporting in the sport of gymnastics, GymCan created a reporting resource page on their website, including external helplines (e.g., Canadian Sport Helpline, Canadian Centre for Child Protection, Kids Help Phone), complaint submission forms, and a GymCan suspended and expelled members list.

3. #MeToo Movement

According to Hostermann and colleagues,[14] the phrase “Me Too” has been used to empower survivors to share their experiences of sexual assault since 2006. However, the phrase gained momentum in the public sphere in 2017 when actor Alyssa Milano posted a social media request for her followers to comment #MeToo if affected by sexual assault after revealing she was assaulted by producer Harvey Weinstein.[15] Since then, #MeToo has empowered millions of individuals worldwide from diverse industries to share their stories of maltreatment in solidarity and advocate for accountability for these experiences.[16]

4. GymCan Community-Wide Call for Safer Environments

In addition to the key factors listed previously, there was recognition and acknowledgment from stakeholders in the Canadian gymnastics community that a cultural shift towards enhanced policy, education and advocacy that prioritized participant well-being and safety was necessary. The first step towards realizing this overarching goal was to hire a full-time employee to conceptualize the organization’s Safe Sport Framework and manage the corresponding program.

In summary, these four key factors contributed to the creation of a dedicated safe sport portfolio at the national governing body for gymnastics and the hiring of a full-time employee to facilitate the program. Once the full-time employee was in place, development of GymCan’s Safe Sport Framework began. The following section provides an overview of the general purpose of the Safe Sport Framework as well as an outline of the six key steps engaged in by GymCan to facilitate development of the Framework.

Developing GymCan’s Safe Sport Framework

The Safe Sport Framework is GymCan’s Strategic Plan for safe sport created with the purpose of minimizing risks and strengthening the administration and delivery of all programs, events, and services. The overarching goal of the Safe Sport Framework is to encourage a cultural shift towards more positive, inclusive, and healthy gymnastics environments from grassroots to the national level. The framework document includes the organization’s purpose, philosophy and principles, topic areas, pillars, objectives, and corresponding initiatives related to Safe Sport.

Each of these key components is described in the following section. It is important to note that when the Safe Sport Framework was conceptualized in 2018, it was considered an ever-evolving document that would be reviewed, revised, and expanded upon as the organization continued to make enhancements in the area of policy, education and advocacy.

Initial Implementation of the GymCan Safe Sport Framework

Throughout this section, we provide insight into the initial approach GymCan took to operationalize the Safe Sport Framework and provide a few practical examples of policy, education, and advocacy initiatives completed to date.

Safe Sport Policy. In accordance with the Safe Sport Framework and corresponding prioritization of initiatives, the first pillar undertaken by GymCan was policy. This pillar was selected to ensure there was a solid foundation and set of clear principles in place to establish expected standards for behaviour and promote accountability in the environment. The overarching objectives for policy development and implementation are as follows:

- Develop a Safe Sport policy suite with enhanced focus on participant welfare, safety, and protection;

- Ensure all policies and procedures related to Safe Sport are robust, clear, up-to-date, and accessible;

- Identify and address existing gaps in policies and procedures related to Safe Sport;

- Closely align GymCan policies and procedures with Provincial and Territorial gymnastics organizations and ensure consistent enforcement across all levels of gymnastics in Canada; and

- Determine and implement an appropriate process for managing reports of misconduct.

Across all objectives, GymCan aims to ensure that participant welfare is at the forefront of all policy development, commits to regular review and updates of the policies following the initial revitalization of the policy suite, recognizes the need to develop independent and expert-led processes that remove decision-making power from the NSO in disciplinary cases, and strives to ensure that participants across the country are operating under similar expectations of practice and standards of care.

With the core objectives in mind, the first phase of Safe Sport policy revitalization included the following:

- Creation of a National Safe Sport Policy;

- Revision of the Code of Ethics and Conduct;

- Creation of a Maltreatment and Discrimination Policy;

- Revision of the Complaints and Discipline Policy;

- Creation of a National Travel Policy; and

- Creation of a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Policy.

Figure 12.6 Phases of Safe Sport Policy Revitalization

Navigate through the interactive flip cards using the right and left arrows at the bottom. Flip the card over to read more about each each of the policies included in safe sport policy revitalization.

From a broad perspective, policies and procedures related to safe sport require continuous expansion, refinement, and updates as new evidence (e.g., research, lived experiences, learnings) becomes available to enhance expected standards, knowledge, and practice. Click here to view GymCan’s up-to-date Safe Sport policies.

Finally, in conjunction with safe sport policy updates, it is also critical to engage in ongoing review and revision of organizational documents to ensure the same principles and standards for behaviour outlined in the policies are incorporated throughout all operational documents and procedures. For instance, as part of the safe sport policy suite revitalization, GymCan’s National Team Agreement, National Team Responsibilities Manual, and the National Team Handbook were revised to incorporate updated terminology, roles/responsibilities, best practices and conduct expectations for positive, healthy and athlete-centered national team environments.

Safe Sport Education. Implementation of educational measures are integral to enhance knowledge and develop reasoning and judgment, as well as foster positive interactions and practices in the community. The following core objectives serve to guide the educational initiatives designed and implemented by GymCan:

- Establish a basic understanding of Safe Sport across all stakeholders in the GymCan community;

- Procure and generate evidence-based educational resources and practical tools to advance Safe Sport;

- Ensure individuals who witness or experience potential misconduct understand the process and channels for reporting; and

- Integrate the Safe Sport mandate across multiple formats in a consistent and accessible manner.

With these objectives, GymCan aims to build knowledge and capacity to create, maintain, and foster safe, inclusive, and positive environments for all participants. To provide context to the organization’s approach to Safe Sport education, it is important to consider that the core focus in the early years of safe sport programming was policy development with the intention to strengthen the foundation for safe sport at GymCan. As a result, to date, Safe Sport education at GymCan has been implemented in a variety of both short-term and long-term ways that the organization intends to build upon with a refined focus in the future.

Included in these initial Safe Sport educational initiatives are mandatory training mechanisms for key stakeholders in the GymCan community in accordance with Sport Canada, including the Respect in Sport for Activity Leaders certification, as well as custom in-person workshops for GymCan’s National Teams (e.g., athletes, coaches, judges), and optional community-wide learning activities. For example, GymCan’s Safe Sport Learning Series takes an evidence-based approach to safe sport education by pairing expert researchers with a practitioner or individual with lived experience to share knowledge and provide concrete strategies to help influence and inspire a more athlete-centered, positive and healthy culture in practice.

Further, GymCan encourages self-directed learning through the Safe Sport section of GymCan’s website, which provides links to the organization’s up-to-date safe sport policies; free resources covering a variety of topics related to maltreatment, equity and inclusion, health and wellbeing, and concussion; information and resources for reporting concerns within and outside of GymCan; and connections to external helplines for assistance on a variety of topics, such as mental health, welfare concerns, and inclusion .

Safe Sport Advocacy. Throughout the development of policy and implementation of education initiatives, GymCan has also engaged in different avenues for safe sport advocacy. There are two key objectives that foster the advocacy initiatives at GymCan (see Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 GymCan Key Objectives for Safe Sport Advocacy Initiatives

| Advocacy Objective #1 | Advocacy Objective #2 |

| Actively promote GymCan’s commitment to Safe Sport and enhance visibility in the gymnastics community and beyond. | Positively contribute to an athlete-centered culture in sport through collaboration with Safe Sport leaders and external experts. |

In consideration of these two key objectives, GymCan engages in a variety of strategies to support advocacy for safe sport within gymnastics specifically, and the Canadian sport system more broadly. For instance, GymCan’s national platform is leveraged to foster connections and build community relationships with other NSO, MSO, and professional sport partners nationally and internationally to drive culture change system-wide. This includes participation in the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport Working Group, participation in the International Gymnastics Working Group for Safe Sport, and collaborations with values-based sport partners (i.e., True Sport) to develop learning materials and elevate the impact of our collective voice for safe sport.

In addition, GymCan’s national platform is leveraged to galvanize public support on issues related to safe sport through consultations, presentations, media interviews, and signing or developing written communications, such as position statements or letters to government. Further, to maximize the influence of GymCan in the safe sport realm, the social media channels (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) for the organization are used to promote learning opportunities and demonstrate GymCan’s participation in external events aimed at building capacity or supporting key issues under the safe sport umbrella, such as participation in the Capital Pride Parade. Advocacy is a critical method for encouraging the prioritization of safe sport across the Canadian Sport System.

Considerations for the Pathway Forward

The sport environment is often referred to as a microcosm of general society (Cunningham, G. B., & Welty Peachey, J. [2012]) and thus, it is the responsibility of sport leaders to ensure that the management of the sport system properly reflect societal norms, standards, and expectations. In recent years, the #MeToo movement and an enhanced global focus on gender and power inequity in sport have highlighted the critical and immediate need for sport to change the culture and modernize both its systemic and organization-specific architecture, policies, and procedures.

-

Photo by Victor Freitas on Pexels. Though the concept and philosophy of safe and healthy sport is not new, the “safe sport movement” has gained significant traction over the last decade due to troubling stories bravely shared by athletes from many different sports about the realities of their athletic experiences. These revelations have led to heightened awareness and an urgent call for enhanced equity, access, and safety within the culture and structure of sport.

For gymnastics, specifically, an outpouring of cases and significant concerns regarding the maltreatment of athletes have been highlighted across the globe. In response, independent cultural reviews of gymnastics have recently been facilitated via external agencies in many countries, including, Belgium, Netherlands, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. The findings from these investigations have been disturbing (e.g., stories of humiliation, control, threats, weight management, blackmail, training through significant injuries, culture of fear), and are a lesson to leaders in all sports as to their responsibilities to provide a safe, healthy, and inclusive environment for all participants.

A few examples of the recommendations for organizations to facilitate culture change gleaned from the investigations concluded to date are:

- Identify and train child safeguarding representatives across all organizations within the sport structure (i.e., national governing body, provincial members, clubs);

- Transform education to holistic, athlete-centered skills development for coaches;

- Strengthen coach engagement and accountability (e.g., mentorship networks, accurate coach registries);

- Broaden the sport’s knowledge and understanding of maltreatment;

- Encourage, promote, and enhance athlete empowerment and participation (e.g., increase athlete voice, conduct surveys and health assessments, create youth councils, encourage athlete career planning, empower athletes to make choices);

- Acknowledge and apologize to members who have experienced maltreatment;

- Develop training and support for disordered eating, body image, and weight management practices to improve consistency and support effective implementation;

- Establish a national coaches’ association to provide support, advice, and professional development;

- Ensure confidential and third-party external investigation of concerns;

- Review and update governance structure and align with best practices;

- Review competition and training attire to address the safety and physical, psychological, and holistic well-being of athletes; and

- Ensure gymnastics clubs prioritize safe sport and establish an ongoing commitment to positive culture within the board, with the parents, with the athletes, and with colleagues.

For gymnastics in Canada, the development of the Safe Sport Framework represents the first step of an essential path to enhanced awareness, policies and procedures, education and advocacy for safe sport. To date, some significant progress with respect to safe sport legislation, operations, and engagement has been implemented. However, there is still much work to do to foster and ensure a renewed culture that prioritizes safe, positive, and inclusive environments above all else for all participants across Canada.

The next step for GymCan and its Provincial/ Territorial partners is to assess existing gaps and continue to refine policies and procedures to enhance protection of vulnerable participants and mitigate the unequal power relations that enable maltreatment, develop educational resources and tools to elevate behaviour and practices, create increased opportunities for athlete voices, and address historic issues while developing the foundation for an athlete-centered and holistic culture. In addition, GymCan commits to supporting the Canadian independent safeguarding organization (launching in 2022) and considers the initiation of this organization as a critical step forward for the entire sport system. Finally, the findings emerging from gymnastics cultural reviews worldwide must be reviewed and incorporated into the organization’s strategic planning and next steps for Safe Sport.

Ultimately, the path to Safe Sport has no end – sport must continually adapt and change to align with cultural and societal expectations, while prioritizing the health and well-being of participants. It is our hope that GymCan’s process to develop the Safe Sport Framework outlined throughout this chapter is helpful to students and future sport practitioners, and is recognized as one national sport’s attempts to begin building a stronger foundation for a better future. Finally, it is imperative as sport practitioners that we continue to learn, evolve, and elevate knowledge, understanding, and practice to ensure safe, healthy, and inclusive sport environments for all Canadians.

- FIG, n.d. ↵

- Kilijanek & Sanchez, 2020 ↵

- Kilijanek & Sanchez, 2020 ↵

- Kilijanek & Sanchez, 2020 ↵

- Andrews, 2010; Hecimovich, 2004 ↵

- Ericsson et al., 1993 ↵

- Gymnastics BC, n.d. ↵

- Kirby, 2018 ↵

- Kirby, 2018 ↵

- Kirby, 2018 ↵

- Macur, 2020 ↵

- Jalonick, 2021 ↵

- Willson et al., 2020 ↵

- Hostermann et al., 2018 ↵

- Hostermann et al., 2018 ↵

- Hostermann et al., 2018; Zacharek et al., 2017 ↵