6 Jurisdiction

Marcus Mazzucco

Hilary Findlay

Themes

Sports law

Jurisdiction

Contracts

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Define the concept of jurisdiction and how it relates to sport bodies adopting and implementing the UCCMS;

L02 Identify three types of contracts that can be used to acquire jurisdiction in sport;

L03 Explain how the monopolistic character of sport governing bodies assists in acquiring jurisdiction; and

L04 Explain the importance of differentiating between members and non-members of an organization.

Overview

This chapter examines the jurisdiction of sport bodies to implement and apply the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). At the national sport governing level, application of the UCCMS will need to extend beyond the scope of authority of federally funded sport organizations in order to capture those who are not members of those organizations, such as coaches and athletes. This extension of jurisdiction can be accomplished through contractual means. The further application of the UCCMS to provincial, territorial, and local levels of sport becomes more complex and raises important questions about the use of contract law to establish a sport body’s jurisdiction.

Key Dates

As of March 31, 2021, national level sport organizations (NSOs) accepting funding from Sport Canada must adopt and integrate the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) into their organizational policies and procedures.[1] As part of adopting this policy, a National Independent Mechanism (NIM) will develop and oversee certain operational aspects of the UCCMS, such as investigations, decision-making, and dispute resolution.[2] The Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) has been selected by the Canadian federal government to act as the NIM. The UCCMS has been introduced at the national level to national sport governing bodies with the intent of subsequently expanding it to the provinces and territories and to local club and sport organizations.

Issues of jurisdiction will play an important role in the adoption of the UCCMS by sport organizations along with its associated operational aspects that will be overseen by the SDRCC as the NIM. Jurisdiction refers to the territory or sphere of activity over which an organization’s or individual’s authority extends. In the context of maltreatment in sport, the jurisdiction of the SDRCC and the sport organization are relevant. The SDRCC requires jurisdiction to carry out its investigative, decision-making, and dispute resolution functions. The national sport organization is essential in assisting the SDRCC in obtaining this jurisdiction through its legal relationships with sport participants. The national sport organization also requires jurisdiction to apply and enforce the UCCMS with sport participants, and to carry out functions that fall outside the authority of the SDRCC.[3]

A sport organization will typically have jurisdiction over its membership in accordance with the terms of its governing documents (for example, its constitution, bylaws, policies, and regulations). It does not have such jurisdiction over non-members, absent a legal relationship with those non-members. Where the scope of application of the UCCMS extends beyond the membership of the national sport governing body, the question thus arises as to what jurisdiction a national sport body has to apply and enforce the terms and conditions of the UCCMS (including the powers of the NIM charged with managing procedural aspects of the UCCMS) on both members and non-members? What considerations apply to extending the UCCMS to provincial and territorial governing bodies as well as to local clubs and associations?

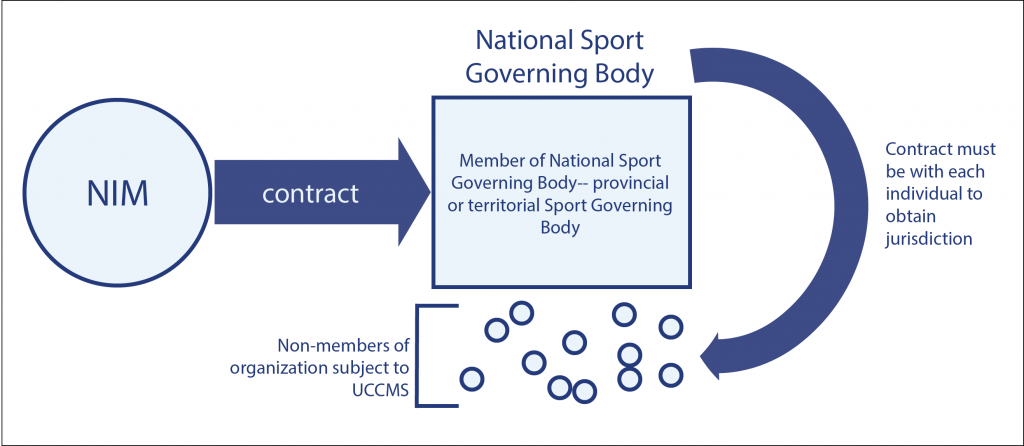

This chapter examines the issue of jurisdiction at the national, provincial and territorial, and local levels. Specifically, we examine the ways by which a sport organization can take jurisdiction over a matter and the limitations placed on such jurisdiction. A summary of the contractual landscape is discussed in the following section and set out in Figure 6.1 (see below).

Adopting the UCMMS by Contract

There are two mechanisms by which an entity generally gains jurisdiction: through legislation or by contract. In the Canadian context of maltreatment in sport, sport governing bodies will have obligations to implement the UCCMS through direct contractual relationships with Sport Canada, and the NIM (SDRCC) will obtain jurisdiction through contractual relationships between sport governing bodies and participants. In the United States, on the other hand, the jurisdiction of the Center for SafeSport and the requirement for national governing bodies to adopt, apply and enforce the SafeSport Code arise from legislation.[4]

Legislation is arguably the better instrument where the rules are meant to be truly mandatory for all.[5] However, the federal structure of the Canadian landscape makes that impractical, if not impossible. Sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 distribute legislative authority between the federal government and the provinces and territories. Section 92 assigns authority over matters related to property and civil rights, which encompasses most aspects of sport. There is no federal legislative authority by which sport organizations can be compelled to adopt either the UCCMS or the operational aspects of the NIM. While provincial and territorial legislation remains a theoretical option, it is unlikely that every provincial and territorial government would enact legislation that requires the adoption of the UCCMS by sport organizations operating in their jurisdictions when such a requirement can be achieved through contractual means. If provincial and territorial legislative action cannot be coordinated and consistent, then it would risk a further fragmentation of safe sport initiatives that already exist in Canadian sport.

The following sections describe the various levels of contracts that are required to apply and enforce the UCCMS in Canadian sport.

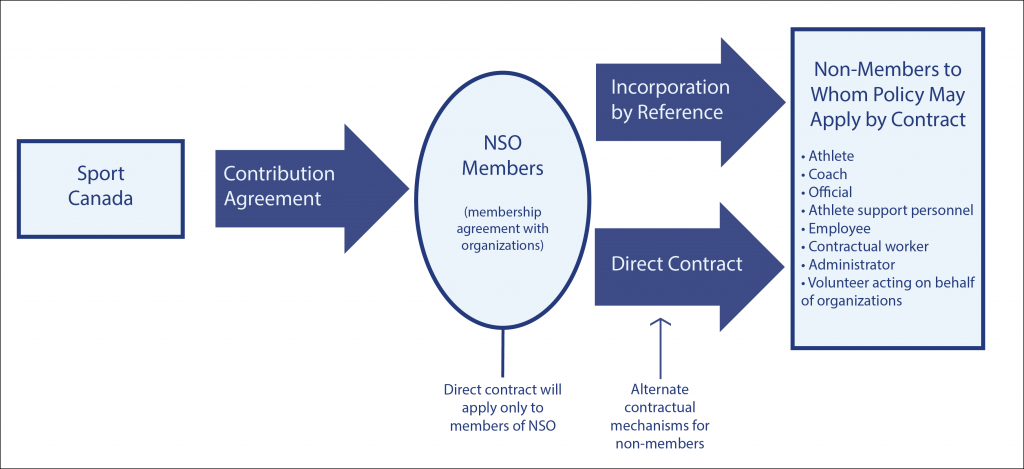

Figure 6.1 Legal Relationships Between SDRCC, Sport Organizations and Participants

The Nature of Contract

It is generally accepted that contracts are the backbone of sport.[6] Indeed, it is said “the authority of private or domestic tribunal is derived solely from contract, that is, from the agreement of the parties concerned”[7] and “the authority of the sport governing body is purely consensual, arising from the membership agreement between the organi[z]ations and its members.”[8] And again, “[t]he application of the rules of associations to members is founded on the voluntary relationship between association and member.”[9]

To be valid, and thus enforceable, a contract must meet certain legal requirements. Traditionally, these have included an offer, acceptance of that offer, consideration (or benefit) flowing between the parties in the form of reciprocal promises and, finally, an intention by the parties to be legally bound. There are other inherent characteristics that bring effect to these requirements and that are recognized as part of the contractual relationship between an organization and its members. Specifically, an agreement must be both voluntary and consensual.

Contracts between Sport Canada and National Sport Governing Bodies

The crafting of the UCCMS and the selection of the NIM to oversee implementation of the policy is the result of the collective action of the sport community.[10] The first level of contract needed to successfully implement the UCCMS is between Sport Canada and federally funded sport organizations – known as the Contribution Agreement. Through the Contribution Agreement, Sport Canada has made federal funding contingent upon the adoption of the UCCMS.[11] Most Canadian sport governing bodies are supportive of a pan-Canadian policy for dealing with maltreatment in sport and have entered into this funding agreement with Sport Canada wherein they have adopted the UCCMS in exchange for federal funding through a Contribution Agreement. However, a problem arises with regard to the jurisdiction of national sport governing bodies to apply and enforce the UCCMS.

The Contribution Agreement between the national sport governing body and Sport Canada stipulates that anyone “affiliated” with the organization shall be subject to the UCMMS. The Contribution Agreement goes on to define “affiliated” persons:

“For the purposes of this Agreement, “individuals affiliated with the organization” includes an athlete, a coach, an official, an athlete support personnel, an employee, a contractual worker, an administrator or a volunteer acting on behalf of, or representing the recipient in any capacity.” (Annex A, Section 5, Contribution Agreement as cited in McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020)

The above definition is problematic in two respects. First, it does not distinguish between members and non-members of a sport organization. As discussed further below, a sport organization is more likely to have a contractual relationship with members than non-members. Athletes and coaches are not typically members of a national sport organization and, therefore, a sport organization must enter into separate contractual relations to have jurisdiction over these individuals. Second, the definition does not include the provincial or territorial sport organization members of a national sport organization, which leads to a missed opportunity to apply the UCCMS to the provincial and territorial levels of sport.

The following sections discuss how a sport organization obtains contractual authority over members and non-members and how the jurisdiction necessary to administer the UCCMS at the provincial, territorial and local levels of sport could be obtained through contractual means.

Contractual Authority of Sport Organizations over Members

Sport governing bodies can only implement policy, and specifically the UCCMS, to the extent they have jurisdiction to do so.[12] The authority of an organization refers to the power or right to make decisions and enforce rules. The authority of an organization must have some legal basis or come from some legal source. The conventional view is that the authority of a sport governing body is derived solely from contract, the contract being the membership agreement between the organization and each of its members.[13] The terms of that membership agreement, or contract, is made up of the governing documents of the organization, including its constitution, bylaws, policies, and rules. Two important points emerge from this proposition:

Point 1: The contract binds only members, not non-members.

Point 2: Even with regard to members, an organization has no inherent authority. It can act only to the extent its rules and policies allow.[14]

Within the Canadian sport structure, membership in most national sport governing bodies is typically confined to other sport governing bodies at the provincial and territorial

level.[15] However, pursuant to the Contribution Agreement that national sport organizations have with Sport Canada, the scope of application of the UCCMS extends beyond the membership of the national sport governing body and thus beyond its jurisdiction. If regulatory power is not underpinned by a contract, and no other legal right to exercise authority is established (such as by legislative provision), there is no legally binding power by the organization over these non-members. In other words, the national sport governing body would not have jurisdiction over all those affiliated persons Sport Canada requires it to have.

Contractual Authority of Sport Organizations over Non-Members

1. Express contracts

The most direct way to achieve jurisdiction over non-members, is through a direct, or express, contractual agreement between the national sport organization and each of the relevant (affiliated) parties over which the organization wishes to have jurisdiction but does not by way of membership agreement. There are several examples of such contracts in sport: the International Olympic Committee (IOC) uses direct contracts between itself and all participants in the Olympic Games. All participants must sign an entry form, which is a form of express agreement whereby participants agree to comply with the Olympic Charter, the World Anti-Doping Code, the IOC Anti-Doping Rules, the IOC Code of Ethics and other IOC guidelines.[16] Closer to home, national sport organizations have athletes sign athlete agreements wherein the athlete agrees, inter alia, to be bound by the rules and regulations of the sport organization. That said, the use of direct contracts by sport governing bodies, particularly at the international and national levels, can be geographically and logistically burdensome and is not typically relied upon.

However, express contracts will exist for non-members of a national sport organization who are employees or independent contractors retained by the organization, which may include some high-performance or national team coaches and staff.

2. Implied Contracts Through Participation

Implied contracts also exist in sport. For example, where a sport governing body hosts a competition, individuals who agree to participate in the competition impliedly accept the technical rules of the sport body that govern the competition. Participation may indicate actual, or constructive, knowledge of the rules of play and consent to such rules, but to suggest it reflects consent to the broader regulatory authority of a sport governing body including the rules and regulations underpinning such authority, is far from the “knowledge” necessary to establish consent to a valid contract. Having regard to the requirements of a legally binding contract, contracts must be consensual. Antecedent to consent is knowledge – the parties must know to what they are consenting. Consent to the regulatory authority of an organization rests on knowledge of those regulations. In Modahl v. British Athletic Federation Ltd.[17] the Court recognized that the sport body’s rules and regulations established “[a] framework of rights and duties of sufficient certainty to be given contractual effect” but was unable to imply from that framework an actual contract between the athlete and sport organization solely on the basis of the athlete’s participation without an actual express, or direct, contract between the parties.

3. “Indirect” Contracts

Most international sport federations attempt to assert jurisdictional authority over non-members, particularly athletes, through the regulatory hierarchy of sport extending from the international sport federation through to the local club. Many national sport governing bodies follow suit by exerting jurisdictional authority over non-members by requiring provincial and territorial organizational members to incorporate and comply with national-level sport policies. The provincial and territorial organizations, in turn, require their members (local clubs, associations and individuals[18]) to incorporate and comply with provincial and territorial policies, which incorporate an indirect requirement to comply with national policies.

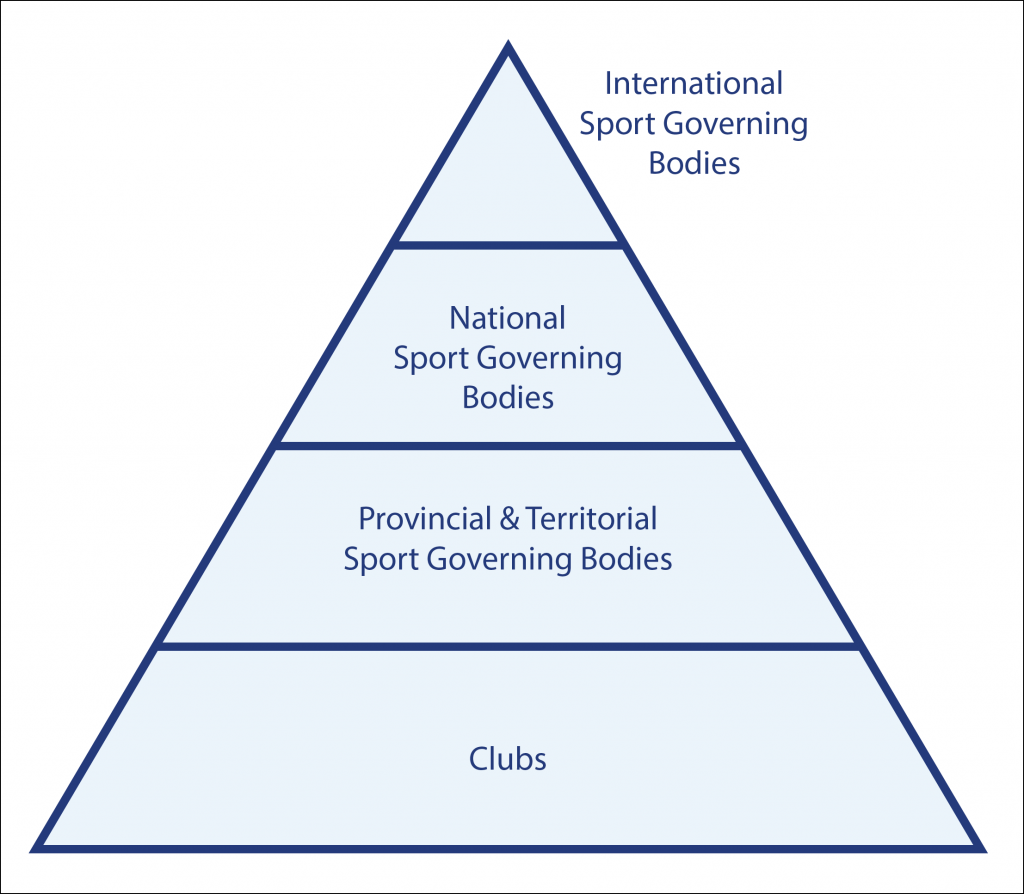

This pyramidal structure of sport results in a “flow through” of rules emanating from the top or apex of the structure through each level ending at the grassroots club level (see Figure 6.2 below). Each successive level of this pyramid structure is bound to the next by consensual agreement between the organization and its members based on the organization’s governing agreement.[19] As such, the members of the national organization, who are the provincial and territorial organizations, are bound by contract to the national organization. In turn, the members of the provincial and territorial organizations, who are typically local clubs, are bound by contract to the provincial and territorial organizations. Finally, individual club members (typically parents and athletes) are contractually bound to their clubs by membership agreements.

Figure 6.2 Pyramidal Structure of Sport Hierarchy

A “chain of interlocking contracts”[20] binding each level of the pyramid to all those above it emerges. In this way, the international governing body can extend its regulatory influence down the entirety of the pyramid, as can the national association and provincial and territorial sport governing bodies.[21] From a contractual perspective this can be problematic. At any particular level of the pyramid, the terms of the contract between member and organization are not necessarily determined between the contracting parties, but instead are imposed by a non-party sitting above the organization in the pyramid.

Figure 6.3 Contractual Options for Acquiring Jurisdiction at National Level

This system of incorporating terms of a contract by reference into the policies of another organization (‘incorporation by reference’) is generally accepted within the governance framework of sport. Technically, it is a fiction to consider rules and regulations that are imposed on organizations and their members and to which the parties have no part in determining, to be part of an actual contract between an organization and its members. As a result, this chain of interlocking contracts has been criticized for not meeting the basic requirements for a contract on a number of grounds:[22]

- The content of the agreement is entirely at the discretion of one party – the member has virtually no input into the terms of the agreement thus bringing into question the voluntary nature of the agreement;

- The agreement is not necessarily between the organization and its member but rather is imposed, by a non-party within the pyramid structure and thus not voluntarily accepted by one of the parties;

- The power imbalance between the parties (particularly athletes) is so great as to erode consent;

- The regulatory nature of the relationship is antithetical to the transactional nature of the contractual relationship. Contract is based in a bargain effected between the parties. The organization is obligated to administer its rules and regulations properly and fairly regardless of the existence of any contract. This obligation arises from the rules themselves, not from any contract with the member. Indeed, it exists outside of any contract. There is, arguably, no bargain between the parties.

Despite these flaws in the contractual model, such a system does work because it rests on the monopolistic status of governing sport bodies.[23] In essence those who wish to be involved in the sport have no choice but to submit to the authority of the regulatory body, even if that authority has no legal source. In order for a sport to operate with consistency and certainty, such monopoly is necessary and indeed, is an inherent characteristic of sport. It is also the way sport governing bodies can exert control over non-members even in the absence of a true contract.

“In terms of the analysis of the nature of the power of sports governing bodies, monopoly power is to be understood as a fundamental ingredient of the de facto power of sport governing bodies.”[24]

If a regulatory body requires participants to follow the UCCMS as a condition of participating in the sport, then that requirement will be respected in practice and is a reflection of the de facto power of the sport body.

Jurisdiction at the Provincial and Territorial Sport Governing Body and Local Club Levels

A survey by McLaren[26] indicates that many provincial and territorial sport governing bodies support aligning their policies and regulations with a single national system as the most effective way to address and prevent maltreatment in sport. As self-governing entities, these sport bodies could integrate the nationally adopted UCCMS into their own governing structure – either voluntarily or by obligation in accordance with their membership contract with their national governing body. Provincial and territorial governing bodies could apply and enforce the UCCMS with regard to their members (local clubs and associations) and use express contracts to take jurisdiction over non-members whom they may wish to make subject to the UCCMS. A particular issue arising as the application of the UCCMS moves to the provincial and territorial and local levels is the capacity of the sport bodies to administer the UCCMS and whether the NIM will provide investigative, decision-making and dispute resolution services at these levels.

The McLaren survey suggests a number of national sport governing bodies and provincial and territorial governing bodies have aligned at least some of their existing policies with their respective national governing body, thus giving those national policies jurisdiction beyond the national level . As noted by McLaren :

“[s]ome of these [national sport organizations (NSOs)] have developed contractual agreements with their affiliated organizations that stipulate compliance with NSO policies concerning maltreatment (for example, reporting, education, and dispute resolution). Therefore, these NSOs are positioned to have the authority to mandate compliance as it concerns implementation of the UCCMS”.[27]

There are other avenues through which jurisdiction can be acquired over a particular group and in a consistent fashion. The UCMMS, or some iteration of it, could be made mandatory at the provincial and territorial levels by leveraging the funding authority that provincial and territorial governments have over provincial and territorial sport governing organizations. Provincial and territorial sport organizations receive public funding, directly or indirectly, from provincial and territorial governments, and compliance with the UCCMS could be a condition of these funding arrangements.

This approach would mirror the contractual relationship between Sport Canada and federally funded sport organizations. This is perhaps the only way to ensure the same policy and policy provisions are adopted by every sport governing body receiving provincial or territorial funding. Provincial and territorial governments could also make it a condition of funding that provincial and territorial sport organizations require adoption of the UCCMS by their member local clubs. As at the national level, the provincial and territorial governing sport bodies could exercise their contractual or de facto power to require the adoption of the UCCMS by their local club members.

Unincorporated Groups

There is a final group to consider. There are organizations, particularly at the community level, in which people come together in pursuit of a common goal but do not have an intention to create legal relations. Typically, these organizations are unincorporated but may have a constitution, bylaws and a governing body in order to bring some organization to their common pursuit. Members of such a group do not enter into enforceable legal obligations just because they have joined a group with rules that all are expected to follow.[28] This might be the case for a local hockey club playing in a league or a dragon boat club participating in a schedule of competitions. These clubs are not members of any provincial or territorial governing body though individual participants may be selected to provincial or territorial teams. For a provincial or territorial sport governing body to exercise jurisdiction over such groups they must enter into a direct contractual relationship with each individual in the group.[29]

Further Research

One of the goals of this movement is to work towards a pan-Canadian harmonized approach to dealing with maltreatment in sport. From a jurisdictional perspective, this becomes more complex at the provincial, territorial, and local levels. What ways can harmonization be achieved between organizations operating at different levels and across sports? Does the global anti-doping system provide a helpful precedent wherein sport organizations can adopt their own anti-doping rules as long as the rules meet the minimum standards in the World Anti-Doping Code? Will such organizational discretion be permitted between sports (to account for sport-specific differences) or at various levels of sport (to account for jurisdictional differences) to promote a flexible but harmonized approach?

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Choose a sport organization at the national, provincial/territorial or local level and track how membership is determined. This may best be done by looking online at the organization’s constitution or by-laws for membership rules or viewing the organization’s membership policy.

Image Descriptions

Figure 6.1 This graphic demonstrates the legal relationships between the SDRCC, sport organizations, and participants. The National Independent Mechanism (NIM) signs a contract with a sport governing body (national, provincial or territorial). A separate contract must exist between the sport governing body and non-members of the organization in order for the NIM to obtain jurisdiction. [return to text]

Figure 6.2 This graphic demonstrates the pyramidal structure of sport hierarchy, with clubs listed at the base level, provincial & territorial sport governing bodies listed above on the next level, national sport governing bodies on the next level, and international sport governing bodies at the very top of the pyramid. [return to text]

Figure 6.3 This graphic demonstrates the contractual options for acquiring jurisdiction at the national level. Sport Canada is listed on the left, making a contribution agreement with NSOs. A direct contract will apply only to members of the NSO. Alternatively, incorporation by reference or direct contact are contractual mechanisms for non-members. Non-members to whom policy may apply by contract include the athlete, coach, official, athlete support personnel, employee, contractual worker, administrator, or volunteer acting on behalf of organizations. [return to text]

Sources

Athletics Canada. (2020, July). Athletics Canada bylaws. https://athletics.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Athletics-Canada-Bylaws-July-2020.pdf

Beloff, M., Kerr, T., & Demetriou, M. (1999). Sports law. Hart Publishing.

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (2020). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), (5)1, 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church of Canada St. Mary’s Cathedral v. Aga, 2021 SCC 22

Field Hockey Ontario. (n.d.). Memberships: Faqs. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.fieldhockeyontario.com/membership

Foster, K. (2019). Global sports law revisited. Entertainment and Sports Law Journal, 17(1), pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.16997/eslj.228

Freeburn, L. (2018). Regulating international sport: Power, authority, and legitimacy. Brill Nijhoff.

Heil, J. (2021, June 29). Safety in sport is everyone’s issue. Vancouver Sun. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://vancouversun.com/opinion/jennifer-heil-safety-in-sport-is-everyones-issue

Highwood Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Judicial Committee) v. Wall, 2018 SCC 26

International Olympic Committee. (2020, July 17). Olympic charter: Bye-law to rule 44. p. 79. https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/General/EN-Olympic-Charter.pdf

Karstens-Smith, G. (2021, July 13). Canada’s safe sport program still in need of change. The Canadian Press. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/summer/olympian-jennifer-heil-says-changes-still-needed-canada-safe-sport-program-1.6101870

Lee v. Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain [1952] 2 QB 329

McLaren Global Sports Solutions. (2020). Aim High: Independent approaches to administer the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport in Canada, final report. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/MGSS-Report-on-Independent-Approaches-December-2020.pdf.

Modahl v. British Athletic Federation Ltd. [2002] 1 WLR 1192 at 103

Nagra v. Canadian Amateur Boxing Association (12 January 2002), unreported decision of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, file no. 99-CV-180990

Ontario Soccer. (n.d.). District member: Contact your local district members. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.ontariosoccer.net/district-members

Patriotic and National Observances, Ceremonies, and Organizations, 36 U.S.C. 2205 (2009). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2009-title36/USCODE-2009-title36-subtitleII-partB-chap2205

Smart, Z. (2021, July 2). Heil, top Canadian athletes call on federal government to address gaps in safe sport system. CBC Sports. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/summer/jennifer-heil-canadian-olympians-paralympians-open-letter-1.6088744

Sport Information Resource Centre (SIRC). (2019, December). The UCCMS context document: Re: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), version 5.1. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-Distribution-to-NSOs-MSOs-FINAL.pdf;

Sullivan, A. (2010). The role of contract in sports law. Australian and New Zealand Sports Law Journal, 5(1). Retrieved December 5, 2021, from http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ANZSportsLawJl/2010/2.html

Swim Ontario. (n.d.). Swim Ontario membership. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from http://www.swimontario.com/news_detail.php?id=52

U.S Centre for Safe Sport. (n.d.a). Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org

U.S Centre for Safe Sport. (n.d.b). Safesport code. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org/response-and-resolution/safesport-code/

- Section 5.1.3 of Annex A of the Sport Canada Contribution Agreement as cited in McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020 ↵

- Except in cases involving an alleged sexual mistreatment of a minor, organizations can choose to opt out of the process overseen by the NIM (Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada) and manage the process themselves (though they may not opt out of the non-procedural aspects). It seems unlikely this will happen given the efficiencies of using the independent process and the general inclination of the sport community to adopt a single independent process for handling matters of maltreatment in sport. (SIRC, 2019; McLaren Global Sports Solutions, 2020) ↵

- As noted by McLaren Global Sports Solutions (2020), certain investigations and decision-making processes may fall outside of the independent body’s exclusive jurisdiction over allegations of sexual maltreatment, grooming, serious physical abuse, and consensual sexual activity with a person over the age of majority. The sport organizations can choose to provide these investigative or decision-making services (through the use of another independent third party, or request that the SDRCC provide these services. ↵

- U.S. Code, Chapter 36, section 2205 imposes obligations on the USOPC and NGBs to comply with the SafeSport Code, and assigns responsibility to the U.S. Center for SafeSport to administer key aspects of the safe sport program. ↵

- There is no consensual element to legislated obligations whereas a key characteristic of contract is its consensual nature. One may query whether the relationship between Sport Canada and the national sport governing bodies reflects a true contractual relationship with meaningful input and consent to the terms of the contract in the situation where, for most sport governing bodies, their financial welfare depends on government funding. ↵

- Sullivan, 2010; Freeburn, 2018, pp. 19-; Beloff et al., 1999, pp. 22- ↵

- Lee v. Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain, 1952 ↵

- There is no consensual element to legislated obligations whereas a key characteristic of contract is its consensual nature. One may query whether the relationship between Sport Canada and the national sport governing bodies reflects a true contractual relationship with meaningful input and consent to the terms of the contract in the situation where, for most sport governing bodies, their financial welfare depends on government funding. (Freeburn, 2018, p. 9) ↵

- Sullivan, 2010; Freeburn, 2018; Beloff et al., 1999 ↵

- SIRC, 2019 ↵

- Federal funding makes up a significant portion of the budgets of most national sport governing bodies that most organizations cannot afford to lose. ↵

- Except in cases involving an alleged sexual mistreatment of a minor, organizations can choose to opt out of the process overseen by the NIM (Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada) and manage the process themselves (though they may not opt out of the non-procedural aspects). It seems unlikely this will happen given the efficiencies of using the independent process and the general inclination of the sport community to adopt a single independent process for handling matters of maltreatment in sport. (SIRC, 2019; McLaren Global Sports Solutions, 2020) ↵

- There is no consensual element to legislated obligations whereas a key characteristic of contract is its consensual nature. One may query whether the relationship between Sport Canada and the national sport governing bodies reflects a true contractual relationship with meaningful input and consent to the terms of the contract in the situation where, for most sport governing bodies, their financial welfare depends on government funding. (Freeburn, 2018, p. 20) ↵

- Sullivan, 2010; Freeburn, 2018; Beloff et al., 1999 ↵

- See, for example, Athletics Canada at https://athletics.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Athletics-Canada-Bylaws-July-2020.pdf.ca; Soccer Canada at https://canadasoccer.com ↵

- The National Olympic Committee is responsible for ensuring all participants complete entry forms. International Olympic Committee, Olympic Charter, 17 July 2020, Rule 44(2) at p. 79 ↵

- Modahl v. British Athletic Federation Ltd., 2002 ↵

- For example: Swim Ontario membership is made up of clubs; Soccer Ontario membership is made up of various associations, leagues and individuals; Field Hockey Ontario membership is made up of individuals, clubs and teams. ↵

- One may question the ultimate source of authority of the highest level of the pyramid. This is an important consideration as, without some legal source of authority, any exercise of authority is arguably invalid. The law of sport has been described as an autonomous transnational legal order and as such, is outside the control of nation states and their legal orders. (Foster, 2019) As private organizations, organized as monopolies, sport governing bodies have been viewed as self-governing. ↵

- "But there can be no doubt that the law of contract is the cornerstone on which ‘Sports Law’ has been built…" (Sullivan, 2010, p. 3; Freeburn, 2018, p. 70) ↵

- See for example Nagra v. Canadian Amateur Boxing Association, 2002 unreported decision of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, where the international association required the national association to adopt a ‘clean shaven’ rule. ↵

- “But there can be no doubt that the law of contract is the cornerstone on which ‘Sports Law’ has been built…" (Sullivan, 2010, p. 3) ↵

- This monopolistic state of governing bodies is another reason to question the consensual nature of the relationship between organizations and their members and its contractual underpinnings. ↵

- There is no consensual element to legislated obligations whereas a key characteristic of contract is its consensual nature. One may query whether the relationship between Sport Canada and the national sport governing bodies reflects a true contractual relationship with meaningful input and consent to the terms of the contract in the situation where, for most sport governing bodies, their financial welfare depends on government funding. (Freeburn, 2018 p. 100) ↵

- Except in cases involving an alleged sexual mistreatment of a minor, organizations can choose to opt out of the process overseen by the NIM (Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada) and manage the process themselves (though they may not opt out of the non-procedural aspects). It seems unlikely this will happen given the efficiencies of using the independent process and the general inclination of the sport community to adopt a single independent process for handling matters of maltreatment in sport. (McLaren Global Sports Solutions, 2020, p. 36 ↵

- Except in cases involving an alleged sexual mistreatment of a minor, organizations can choose to opt out of the process overseen by the NIM (Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada) and manage the process themselves (though they may not opt out of the non-procedural aspects). It seems unlikely this will happen given the efficiencies of using the independent process and the general inclination of the sport community to adopt a single independent process for handling matters of maltreatment in sport. (McLaren Global Sports Solutions, 2020, p. 38-39.) ↵

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020, p. 36 ↵

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church of Canada St. Mary’s Cathedral v. Aga, 2021 SCC 22; Highwood Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Judicial Committee) v. Wall, 2018 SCC 26 ↵

- Once a participant has been selected to a provincial or territorial team, they likely would be required to be contractually bound to the provincial or territorial governing body by an athlete agreement. ↵

Universal Code of Conduct to Address Maltreatment in Sport, promulgated in 2020.

Independent body charged with overseeing operational aspects of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). In Canada, the SDRCC has been named as the NIM to oversee the UCCMS. A regulatory body with the authority to implement safe sport policies.

Jurisdiction refers to the territory or sphere of activity over which an organization or individual’s authority extends.

A formal and legally enforceable agreement between two or more persons.

The power or right to make decisions and enforce rules.

A mechanism of including a second document within another document by only mentioning the second document.

A sector or industry dominated by one corporation, firm or entity.

Self-Reflection

Self-Reflection

In Practice:

In Practice: