Chapter 7: Burnout, Secondary Trauma, Compassion Fatigue & Wellness

47 7.4 Skills – Setting Boundaries

Gemma Smyth

Introduction

There are many possible strategies to prevent burnout and other unhealthy consequences of work-related stress. In this section, we address a universal issue common to every workplace – setting healthy, appropriate boundaries. Typically, ‘boundary setting’ in law has two aspects – setting boundaries with clients and setting boundaries with work colleagues. Here, we focus on setting boundaries with colleagues.

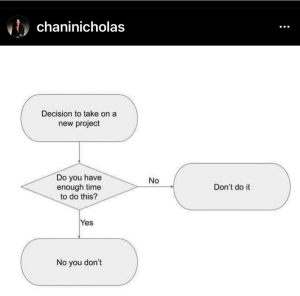

Instagram, @chaninicholas, 2022

Setting Boundaries in Law Practice

Many lawyers who are not sole practitioners often feel at the behest of clients or senior lawyers in a firm. Doron Gold, former lawyer and psychotherapist, describes a common situation in law practice:

“…how many lawyers do you know who take on as much work as their senior partner gives them even if there are nowhere near enough hours in the day to complete those tasks? Some people reading this will most assuredly say that this is the price of being a professional and that we all have to pay our dues. That may have some truth to it, but too many lawyers I see are simply too afraid to set boundaries related to workload and they suffer profoundly as a result. The helpless feeling that comes with being asked to do more than one is capable of doing and not feeling able to say no often leads to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.” (Doron Gold, “The Lawyer Therapist: Healthy boundaries make for healthy lawyers”, Law Times, 19 August 2013, online: https://www.lawtimesnews.com/archive/the-lawyer-therapist-healthy-boundaries-make-for-healthy-lawyers/260980).

Why is it so Hard to Set Boundaries?

As has been a theme throughout this text, there are both individual and systemic aspects of boundary setting. For law students, articling students, or early-career lawyers (and sometimes late-career lawyers!), setting boundaries is intimately connected with the “new political economy of insecurity” (U. Beck, The Brave New World of Work. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000, in Emma Cooke, “The Working Culture of Legal Aid Lawyers: Developing a “Shared Orientation Model”, 2021, online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/09646639211060809).

“Insecurity” in the modern economy manifests in multiple ways, including in the type of work available (service-oriented, contract, lower paid work), the context in which work occurs (rapid technological change, weakened unions, etc), and in the stark divisions arising between people and communities. In this context, it can seem (and be) more dangerous to set boundaries with a principle or supervisor. Power dynamics within a firm, clinic or other setting can also make boundary setting seem like a career-ender.

It can also be more difficult for some people to set boundaries than others. You might have been the member of your family who had to take on leadership responsibilities at a young age. You might have been unable to say “no” because of financial or other forms of insecurity. Research also clearly shows that sex and gender play a role in being able to say “no” without consequence. All these play a role in how socially and culturally acceptable it is to set boundaries.

There are, however, some practical ways to set boundaries in a professional context that preserve the lawyer’s ability to do good work.

Caroline Castrillon notes some helpful tips for setting healthy boundaries in a workplace including:

- setting priorities with your employer (set a list of priorities and negotiate which are most important and which might be postoned or delegated),

- having “off” times, and communicating these to others,

- take time to respond (rather than immediately saying “yes”, wait to figure out if you really do have time and whether others are able to say “yes”),

- creating a structure that works for you,

- being prepared for pushback, especially if you have been a long-time “yes” person.

Instagram, @Litigation_God, 2023

Disability & Setting Boundaries in an Externship

This piece gives a first person account of a Law student with disabilities setting boundaries in an externship context.

Law students are often trying to push themselves both physically and mentally in pursuit of success. For many, this “success” is attributed to high-paying, high-status Bay Street jobs and many of us feel the need to do whatever it takes to achieve that goal. Often something that isn’t talked about enough is the struggles that law students face because of this increased competition. Although chronic illnesses are generally associated with the elderly or disabled, chronic conditions are widespread among working-age adults. A recent study found that the number of working-age adults with a major chronic condition has grown by 25% over the past ten years, to a total of nearly 58 million in 2006. As someone who is suffering from both a chronic, physical illness for which there is no cure in conjunction with mental health issues, I am familiar with the anxiety that can arise from not feeling like you are doing as well as the other people within your program. For this reason, it’s important to emphasize that success can look very different for each individual. At the beginning of the externship placement, many students feel the pressure to prove themselves in the eyes of their supervisors as well as their professors. As a second or third-year student, now is the time when everyone seems to be getting more serious about securing summer employment and gaining helpful exposure in as many areas as possible. Students often get sucked into the madness of trying to prove themselves, to show that they are just as smart and capable as any other law student in Canada. While this is true, those needing additional support certainly are just as capable, many law students are battling with chronic illness and deteriorating mental health in secret. For myself, I was afraid of what my classmates, my professors, my externship supervisor, and even what my friends and family would think if I had to ask for additional support or time to do a task that another law student would jump to complete and likely be able to complete at a quicker rate.

I know that my experience is not an isolated one. According to a survey from 2012 by the Canadian Bar Association (CBA), 58% of lawyers, judges, and law students surveyed had experienced significant stress/burnout, 48% had experienced anxiety and 25% had suffered from depression. The high incidences of mental illness are often a result of excessive working hours, difficulties balancing work and life, and a high-pressure and competitive environment which begins as early as law school. Further, the national standard number of hours does not apply to lawyers as they are excluded from the rules that limit work and allow for the creation of a work-life balance. If you are an individual who suffers from either a physical or mental illness, I strongly urge you to be kind to yourself and not hesitate to ask for whatever additional support you may need. “As attorneys, we are our own worst enemies. We are used to being high achievers in school, and then we work in a field measured by how much we continue to achieve. We put so much pressure on ourselves that we forget to give ourselves a break. Our lives would be better if we could accept that we are human and that all humans make mistakes. Those mistakes don’t define us. It’s OK to be human.

While employers cannot ask about medical conditions before offering somebody a job, they can after one has been accepted if they ask the same questions of every incoming employee. Additionally, employers can’t retaliate against someone who discloses a condition after an offer has been made. While there isn’t a concrete guideline to suggest exactly when a student or legal professional should disclose their physical or mental illness and cannot guarantee the outcome of disclosing during the interview process, I do firmly believe it is important to ask for whatever accommodations you may need upon beginning a new placement. Disclosing physical or mental illnesses can be a scary task. However, disclosing a medical diagnosis early on can be important with conditions that may or are likely to impact the quality of your work at some point. The choice to disclose is largely personal, based on your condition, work environment, and professional relationships, however, you should disclose your diagnosis before the need arises or a safety concern presents itself. This is because if you get ahead and disclose your illness prior, it allows for your workplace to provide you with schedule adjustments or physical accommodations if needed in the future. For some chronic illnesses, there is no cure and flare-ups can occur at any time. I chose to disclose when my condition was at its worst and while everyone was very supportive, I needed schedule adjustments that were never discussed before. After a lot of thought, I decided to talk about it then because my symptoms had progressed to the point where I needed to work differently to continue to be as productive as I would have been before. In my experience waiting to have that conversation at such a difficult time making it very inconvenient for me because I had already begun to undergo more aggressive treatments which made it even more challenging to have that formal discussion with my supervisor. Additionally, if you choose not to disclose your condition and end up failing to meet the requirements of your job, you face increased risks of losing your employment. Your workplace will not be able to provide you with accommodations if they do not know that there is an issue at hand. If you don’t disclose your physical or mental illness and are let go, you also aren’t offered any protection under the Accessible Canada Act because an employee may see your lack of performance as poor performance rather than as a disability or an ailment that requires accommodation.

If you are battling either a physical or mental condition, it is so important to take the time that you need to heal properly. You will heal better with rest than with pushing yourself to work. Additionally, everyone tends to work more inefficiently when they are ill. Navigating a physical illness without having support can cause harm to both your physical and mental well-being. “One of the hardest things about being chronically ill is that most people find what you’re going through incomprehensible—if they believe you are going through it [at all]. In your loneliness, your preoccupation with an enduring new reality, you want to be understood in a way that you can’t be.” Law students seem to thrive on competition, but at the end of the day, they are human too. If you are silently steering through a physical or mental illness, you are never alone and asking for help can only make you stronger.

What if you’ve already said yes?

There are also times students might have said “yes” to a certain task but are ultimately unable to complete it? This Harvard Business Review article has helpful tips on managing this situation: https://hbr.org/2021/09/how-to-say-no-after-saying-yes?utm_source=pocket-newtab