Chapter 3: Context of Law Practice

18 3.2 What do Lawyers Do?

Gemma Smyth and Andrew Pace

Introduction

Most students who graduate from a law school in Canada practice law. Areas of law vary widely, as do the day to day tasks performed by lawyers. By 2L, students have likely met lawyers working in several different contexts, but it is worthwhile spending some time reviewing the many, diverse contexts in which lawyers work. As noted elsewhere in this text, there is no formal differentiation between barristers and solicitors in Canada. As such, a lawyer who is licensed is not limited in terms of where they can work and in what area. However, there is a professional duty of competence (discussed in the Ethics chapter). Because there is such significant difference in the work lawyers actually do, regulators struggle with a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Similarly, what constitutes a meaningful generalist undergraduate Law school curriculum is also subject of debate. This section attempts to challenge some of the common myths surrounding lawyers’ work and identities and introduces some of the common tasks performed by lawyers. It also introduces some of the problems with the business of law as it is currently practiced.

What do Lawyers do?

What a lawyer does daily really depends on the type of law they practice. Some lawyers work purely on policy matters. Others work in in community advocacy contexts. Some lawyers represent single clients while others represent groups of clients. Often, lawyers offer advice to their clients and engage in legal research and various forms of advocacy. Beyond trial, which is less frequent than other responsibilities that lawyers’ have, a lawyer will have the responsibility to research information, draft documents, mediate client disputes, counsel clients on their legal rights and facilitate transactions. Based on how lawyers specialize, daily tasks may vary. Many lawyers do a lot of reading and writing.

Perhaps least exciting, lawyers do a lot of administrative work (scheduling, billing, staff meetings, organising, file management, reporting, and so on). Learning how to complete administrative tasks(including self-management and organisational systems), and how to write documents efficiently are valuable skills.

The Myth of the Gladiator

The general public conceives of lawyering as primarily litigation, dramatic cross-examinations, and elaborate office intrigue. The image of the lawyer-gladiator taking on an unwinnable case but triumphing at trial is powerful – and lawyers themselves can be seduced by it. Pop culture has created images that law students carry with them into their professional career. Lawyers have recognized, through the feedback from their clients, that television creates unrealistic expectations about the law and lawyers. Indeed,

[T]rial stories that offer the most familiar images, characters, and plot forms are the ones most likely to get on the air. Once ensconced there, they are more likely to stick in the viewer’s mind …. In fact, the more they stick the more credible they become. This encourages lawyers and their public relations agents to pitch their clients’ stories in terms of TV reality. In this way, the media’s law stories lend credence not only to the legal reality they portray, but also to the media that portray them. By lending its badge of authority to the popular images and stories it embraces, law enhances not only its own persuasiveness and legitimacy, but also the persuasiveness and legitimacy of the media themselves.

As popular stock images, character types, and plot lines from commercial television acquire enhanced verisimilitude, TV’s commerce-driven, attention- riveting programming increasingly comes to provide models for legal reality. It is as if the familiar images, categories, and story lines disseminated by the visual mass media are supplying cognitive heuristics for society as a whole. And whether true or not, it is on the basis of these compelling images that public policies, criminal statutes, and sentencing guidelines are being drafted and passed into law. (Richard Sherwin, “When Law Goes Pop: The Vanishing Line Between Law and Popular Culture” (2000) at 147).

These narratives are limiting in several ways. The first is that many lawyers do not practice in litigation-based settings. Corporate, transactional, research, mediation, and many other lawyering contexts are typically not portrayed in popular media. Even when lawyers do practice in insurance, civil litigation or other areas in which one might expect media-worthy appearances, the reality of the “vanishing trial” means fewer lawyers spend time in trial (although motions, adjournments, settlement conferences, and so on still occupy the courts’ time).

Expectations – Working Hours

The mythology of the lawyer working through lunch, dinner, and having little connection with their families has some basis in fact, although this might be changing. It is difficult to know exactly how many hours lawyers are billing in their wide range of practice areas. Billable hours are essentially the number of hours a lawyer spends actually working on client files. This excludes time devoted to client development, HR, management, and so on. CLIO, a billable hour tracking software company, noted the following in their annual collection of data (mostly American):

“Most lawyers work more than 40 hours a week. It’s not uncommon for lawyers (especially Big Law attorneys) to work up to 80 hours each week. On average, according to the 2018 Legal Trends Report, full-time lawyers work 49.6 hours each week. Significantly, 75% of lawyers report often or always working outside of regular business hours…”.

The author notes the reasons for these longer hours:

- “Billable hours requirements. When law firms have minimum billable hours requirements, attorneys are required to work a minimum number of hours on billable client work. When these billable hours are combined with the hours spent on non-billable (but still essential) tasks like client intake, research, travel, and communication, it becomes difficult to do everything within a standard workday.

- The catch-up cycle. This struggle is not limited to attorneys at firms with billable hours requirements. The majority of lawyers—77%, according to the 2018 Legal Trends Report—work beyond regular business hours to catch up on work that didn’t get completed during the day.

- Client service. Clients come first and that can impact lawyer working hours. Specifically, the 2018 Legal Trends Report notes that 51% of lawyers work outside office hours to be available to clients.”

The Cadieux et al study examined the connections between billable hour targets and mental health.

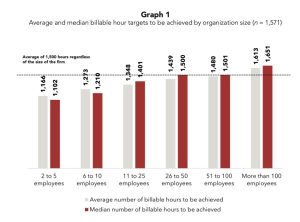

This study found that the larger the firm, the greater number of billable hours are generally expected (see below from page 101).

Unsurprisingly, the higher number of billable hours expected, the higher the number of hours worked – from a low of 46.5 (fewer than 1000 hours) to a high of 65.9 hours (2000 or more billable hours). Higher numbers of billable hours were also connected to avoidance or fear of having a family, inaccurate reporting of billable hours, and significant mental health problems (moderate to severe depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and burnout) (p. 104).

Notably, it was the pressure to meet these billable hours that was the source of many problems (p. 104).

From Instagram, @Litigation_God, 2023.

Where Does the Time Go?

Clio reports the following chart from the 2018 Legal Trends Report. It is clear from this report that lawyers spend about 6.1 hrs a day tending to business and financial needs, 4.5 hours tending to marketing and business development’s needs (including networking and building referrals), and 3.3 hours a day on firm organization and administration (including organizing firm information).

The pandemic has had impacts in various areas of law. In the 2020 CLIO Legal Trends Report, the pandemic caused an initial drop in caseloads across criminal, family, personal injury, and traffic matters. Case numbers returned to a moderate level by August. Other practice areas have remained relatively the same or experienced no changes. Virtual platforms ballooned during the pandemic, and will be a permanent feature of some areas of law. Post-pandemic, 96% of lawyers in the CLIO sample report storing information in the cloud, and 83% report that they will be meeting clients virtually.

Gender, Race & Billing

In her book, You Don’t Look Like a Lawyer: Black Women and Systemic Gendered Racism, Tsedale Melaku notes the importance of the informal mentorship relationships that develop between law firm associates and partners in ways that can exclude racialized lawyers. The discriminatory impacts of these unevenly-distributed relationships results in clear billing disparities, which in turn impacts performance (or perceived performance). She interviewed Black female lawyers in the United States, one of whom is quoted in this excerpt:

“Another reality… is a difference in billing practices between associates of color and their white male colleagues… [A]ssociates of color may not feel comfortable billing a client for certain things, such as thinking about strategies to navigate a deal, whereas white associates are trained to do so through the guidance they receive from partners about proper billing procedure:

“It goes back to staffing. Oftentimes, we [associates of color] aren’t the ones who are initially staffed on a lot of things. And then secondly, billing practices tend to differ. There are all kinds of things that other people are talking about that we aren’t always aware of, like what people are billing for. And they’re legitimately doing things where, if you were just sitting here thinking about, ‘OK, how am I going to do this? Let me just spend sometime planning my mode of attack,” where a lot of times minorities, particularly women, wouldn’t bill for that time. Whereas the white guys are billing when they’re sitting thinking about how they’re going to do something, or they’re in the gym and they’re thinking about whatever. Since they are actively thinking about whatever their matter [dea] is, then they’re going to bill that time…. so then we are always going to end up being farther down in the list of hours. It’s all kinds of little things like that that we are often missing out on that other associates know because some partner at some point told them informally this is how you should do this, and so we don’t get that information.” (Tsedale Melaku, You Don’t Look Like a Lawyer: Black Women and Systemic Gendered Racism (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) at 109-110.

There is more discussion of the power of mentorship – and its uneven distribution – in a later Chapter.

“The New Lawyer”

Canadian and American lawyering has also shifted over the past several decades. Legal work has largely divided into work for personal clients and commercial clients. In her book entitled “The New Lawyer”, Professor Julie Macfarlane notes that “in the last quarter of the twentieth century, the corporate sector grew at a far greater rate than the personal sector”. Chicago lawyers, for example, spent 61% of their time on work for corporate clients, in 1995, compared to 53 percent in 1975. Personal client work dropped 11% since 1975 to 1995. This shift tends to concentrate work into large firms, and perpetuates a culture dedicated to encouraging long hours of work, competitive pay for the best lawyers and low personal autonomy and decision-making abilities for lawyers. Concepts such as billable hours and other productivity-based structures create an environment that is focused on the return on invested time.

Recent CLIO data also suggests that there is also a trend pushing lawyers to use technology more quickly and deeply. The pandemic has simply quickened this trend. As a result, the legal profession is shifting to new ways of conducting work online. The new lawyer may be virtual.

Technostress

The move toward online work has both positive and negative impacts on lawyers. Cadieux’s study examined the phenomenon of “technostress” – stress due to working with technology.

Cadieux draws on the experiences of lawyers and technology:

“Technology was meant to make life easier. Instead, it has increased workload, increased competition (lowering profits), increased demands, and created clients who first need to be corrected before they can be helped.” (Legal Professional 4, p. 116)

“The fast-changing requirements and the stresses being caused by the amount of time now dedicated to learning to adapt to new forms, new filing procedures, new technologies and what stress it is putting on people, firms, court staff and clients. While overall these changes are much needed, the fast pace of these changes are dangerous to the overall profession and public perception of Justice.” (Legal Professional 5, p. 116)

“Our profession needs to take stock of the mental health consequences associated with traditional success, particularly in view of emerging technological changes within the industry.” (Legal Professional 7, p. 116)

Cadieux’s study sheds light on the need for legal workplaces to grapple with the psychological impacts of technostress.

Reflection Questions

- Do you have concerns about the number of hours you might be required to work in your externship? What about in your future employment?

- If you are asked to work hours beyond what is strictly required at your externship, how might you approach this issue?

- What personal and work management systems have you adopted? Are they entirely online? Paper? A combination? What system works best for you and why?

- Do you experience ‘technostress’? What are the main sources of technostress? How has technology made work easier for you?