Chapter 8: Research, Writing & Communication in Law Practice

49 8.1 Legal Research

Meris Bray

Legal Research in the Real World

Practical legal research tends to be quite different from academic legal research, being far more concerned with “what is” than “what might/could be.” This means that the sources you consult, the techniques you use, and the material you produce, are likely to be very different from what you’re familiar with so far in your legal education.

This chapter is intended to introduce you to some of the sources and techniques that will help you be an efficient and effective practical legal researcher, and is intended to reflect one researcher’s perspective on how to approach a problem/question.

Techniques

What’s the Real Question?

Often, the hardest part of beginning the research process is determining what the real question is, and from there, where potential answers might be found. Start your research by asking yourself some of the following questions. You may not be able to answer all of them, and you may have to return to whoever assigned the research to you.

- What’s the scope of the research you’re undertaking? Are you putting together a brief summary of key aspects of a broad area of law, or doing a deep dive on a very particular aspect of a topic?

- What’s the general area of law?

- Use a legal encyclopedia or leading text to see both how the topic fits into the broader area of law, and how it is split into narrower topics.

- Is this a novel topic, or do you know of key or leading cases?

- If there are leading cases, they can be noted up, plus you can use a book’s Table of Cases to quickly find commentary.

- Is there governing legislation?

- Who cares?

- IE what groups/organizations/government bodies etc are involved? Check their websites, blogs, press releases, etc

- Is this a rapidly evolving area of law?

- What is “the answer” going to look like when you find it? Is it going to be a number? A summary of caselaw? A form? A definition?

Make a Plan

Before you dive in to your research, make a plan of where you want to look, and what techniques you’ll use. This might include keywords you want to look for in indices, authors whose work you want to track down, cases to note up, etc. It’s very easy to fall down a rabbit-hole of research, and forget to check a key source.

As you progress through your research, keep track of where you’ve been. Not every research project has a successful conclusion, and sometimes you simply cannot find the answer. Being able to say where and how you looked, can give confidence to whoever you’re sharing your research with that there truly is no answer available, or allow them to spot a gap in your process.

Tools and Sources

Legal Encyclopedias

I usually start my research with one or more legal encyclopedias. They allow me to quickly understand a topic, and how it fits into both broader and narrower areas of law. As well, these can be quick sources to find key words, concepts, and cases to use elsewhere. Start here but don’t end here!

The two major Canadian legal encyclopedias I use are Halsbury’s Laws of Canada (on Lexis+) and the Canadian Encyclopedic Digest (CED, on Westlaw Edge Canada). Both allow you to take a broad look at a hierarchically arranged list of legal topics, with entries that set out basic principles, and cite key legislation and cases.

Halbury’s covers all of Canada, while the CED covers Ontario and the Western provinces. However, one major advantage of the CED is that it contains links to the Canadian Abridgement, which allows you to read a summary of a topic, and then jump directly to relevant caselaw.

Both tools can be searched at the top level (good if you don’t know where your topic might fit in), or at any point as you browse down the tree structure to the actual content.

- Halsbury’s Laws of Canada – video from Lexis Advance Quicklaw, broadly applicable to Lexis+.

- How to start your research with the Canadian Encyclopedic Digest (CED) – video from Thomson Reuters/Westlaw

Secondary Sources: Stand on the Shoulders of Giants

Let leading experts do the heavy lifting! Textbooks and journal articles are a great place to take your research after a legal encyclopedia.

Textbooks

Textbooks help you situate yourself in the broader area of law, providing key words and concepts, setting out how an area of law fits together, and perhaps most importantly, helps you avoid going too specific too quickly. As well, textbooks can help you find suggestions of further readings, key cases, and relevant legislation.

Legal textbooks come in a much broader array of types than conventional academic texts: In addition to conventional bound books, you might also see supplemental updated volumes (these often have an accompanying softbound volume with updates), and loose-leaf binders with regular updated sheets. E-books are often the same titles as loose-leafs.

Find textbooks using the University of Windsor Library Catalogue to find print and e-books that a library has in its collection, at both the Law and Leddy libraries. Not finding a sufficiently practice-oriented textbook? Try the LSO Great Library catalogue, which also searches courthouse libraries across Ontario.

Knowing how textbooks are organized can help you use them efficiently: One of the first pages in a book is the copyright info page, which contains all the information you’ll need to cite the book. Nearly every textbook will have a Table of Contents, which allows you to browse to situate your research in a subject hierarchy. Most legal textbooks have a Table of Cases, where cases are listed alphabetically, with every page on which they are cited. If you already have a case of interest, this helps you quickly find commentary on it and find related cases. Some, but not all textbooks also have a Table of Legislation, and a Table of Sources (secondary material), both of which allow you to find related material. Finally, at the end of the textbook, you should find an Index, where key terms are listed alphabetically, with page numbers where they can be found in the textbook. Indices can, unfortunately, vary widely in quality, so don’t be surprised if sometimes they aren’t as helpful as you’d hope.

Journal Articles

Journal articles are excellent sources when you need timely materials because you’re researching a recent change, or when you’re looking for a broad survey of a topic (especially a broad survey of a narrow topic). Often, journal articles take a narrower focus, in comparison with textbooks.

Unlike academic research, you no longer need to restrict your focus to peer reviewed sources. While still valuable, these sources tend to respond more slowly to changes in law, and are often less practical in focus. Trade publications, on the other hand, focus on timely publication of matters of interest to legal practitioners. They are, truly, “news you can use.”

Index to Canadian Legal Literature (ICLL)

As an Index, ICLL does not contain the actual text of articles. However, while this means you’ll want to be very general in your searching (as you won’t be searching full text, just title, author, subject headings etc), it also means that the ICLL can cover/index a vast array of articles including CPD/CLE, trade and academic journals, and theses and dissertations: Coverage list. Once you have the citation to a promising article, you can then find it in other sources, or ask a librarian for help to retrieve it. ICLL is on both Westlaw Edge Canada, and Lexis+.

- Using the Index to Canadian Legal Literature (ICLL) to find journal articles, government publications and academic thesis (video from Thomson Reuters/Westlaw)

Academic Journals

There are collections of academic legal periodicals on both Westlaw Edge Canada and Lexis+. However, the broadest collection is on Heinonline. A significant advantage to accessing journal articles on Heinonline, when possible, is that the content is scans of the original full text, and as such, the original pagination as well as any diagrams/illustrations etc, are intact.

Trade Publications

Trade publications publish on a monthly, weekly, or sometimes even daily schedule, and therefore respond incredibly quickly to changes in legislation or jurisprudence. As well, they are usually aimed at practicing lawyers, with most of the articles written by practitioners. Some of the most commonly used trade publications are Canadian Lawyer, the Lawyer’s Daily, and Law Times.

CPD/CLE

Continuing professional development/continuing legal education materials are timely and eminently practical. Use them to find material on recent developments in the law, to stay up to date, and when you need practical advice or material. CPD/CLE usually take the form of a lecture/series of lectures by relevant experts (practitioners, council on recent key cases), and attendance usually includes collection of associated material (papers, case digests, forms and precedents, checklists). These seminars and their materials are offered by a range of vendors. The most accessible, and most prolific:

- AccessCLE: All LSO CPD since 2004, available for free. It can be a challenge to search, so when possible, use the LSO Great Library catalogue instead

- OBA/CBA: These materials are available in print at most Courthouse libraries, and via the Great Library.

- PracticePro: Free, and also offers a great range of other free practice resources as well.

- Advocates’ Society: In addition to CPD/CLE available for purchase, this organization also offers a broad range of free “best practices” material.

Legislation

The most common legislative tasks are finding a current act (or regulation), finding how an act read at a certain point/period in time, and seeing how an act looked when it was originally made (as it was published in the Annual Statutes, before amendments, repeals, etc). At both the Ontario and Federal levels, there are fantastic websites to help you complete all of these tasks. However, there are some quirks and key differences between them that are important to keep in mind.

Annual v Revised v Consolidated Law

You’re going to see these terms bandied about below, and used generally in reference to legislation, and it’s important to understand what each one refers to.

Annual

Refers to legislation as it was passed (acts) or made (regulations). Annual statutes appear in the annual statute volumes, while regulations appear in the relevant Gazette for the jurisdiction in question (and for both, their online equivalents and/or a central legislation website for each jurisdiction). You can recognize annual statutes as their citations will start with S and an abbreviation for the jurisdiction, followed by the year: SC 1999 (Statutes of Canada 1999) or SO 1999 (Statutes of Ontario 1999). A regulation’s citation will start with SOR or SI (Federal), or O Reg (Ontario), followed by the regulation number and year (SOR/2000-111; federal, regulation 111 from the year 2000, O Reg 426/00; Ontario, regulation 426 from the year 2000).

Revised

Over time, acts and regulations change… Sections get added, sections get amended, and sections get repealed. This meant that historically, in order to understand what a piece of legislation looked like at a current date, you had to take the original legislation, and then “cut and paste” all the amendments to it. This, obviously, could be an immensely time consuming and confusing process. Hence, the practice of revisions began: Periodically, a jurisdiction would take all of the statutes, regulations, or both that were currently in force, and apply all those amendments that had taken place since the legislation originated (or was last revised). The new collection would be organized, often alphabetically, each piece of legislation would be renumbered to remove repealed sections/add new sections, and published as a set of bound volumes. Historically, this happened in Ontario every ten years, and more sporadically for federal legislation (also, federally, the acts and regulations would be revised at different times). However, thanks to consolidated law, revisions of the entire body of legislation in any jurisdiction are highly unlikely to ever occur again. The final Revised Statutes of Ontario (RSO) and Revised Regulations of Ontario (RRO) were in 1990, and the final Revised Statutes of Canada (RSC) was in 1985. The final revised regulations of Canada, slightly inaccurately named the Consolidated Regulations of Canada (CRC) was in 1978.

Consolidated

Like a revision, consolidated law “folds in” all the amendments since the legislation was made/revised. Unlike a revision, this process occurs on an act by act (or regulation by regulation) basis, when an amendment happens, rather than in a comprehensive way at a certain point in time. Also unlike a revision, the folding in of amendments does not result in a renumbering: This can result in many “point sections” (10.1, 10.2, 10.3) as new sections are crammed into an existing act/regulation, or huge gaps, where sections have been repealed. Both Justice Laws and E-laws are examples of continuing consolidations, providing access to up-to-date legislation on an on-going basis.

Federal: Justice Laws

Justice Laws provides an official source of consolidated federal legislation. Current consolidated law may contain greyed out text: this is material from the original act that is not yet in force. View a list of amendments not yet in force under “Related Information” from an act’s home page. Regulations that belong to an act can be found at the bottom of the act’s home page, or via yellow “R” to right of the act title in the alphabetical list of consolidated acts, or by consolidated regulations list (by title). Select “Previous Versions” from the top of an act’s home page to see consolidated versions of the act from the past. These versions span from one date to another; essentially between amendments, and “[g]enerally, the Point-in-time data is available from January 1, 2003 onwards for the Acts.”

Justice Laws also provides annual statutes from 2001 onwards. These are not official, but are regarded as authoritative. If you need an annual statute from before 2001, most law libraries will hold print annual volumes at least back to Confederation, and often pre-Confederation. HeinOnline also provides scans of the print annual Statutes of Canada from pre-Confederation (1792) through to current. As well, from 1974 to April 2014 (print), and 1974-current online, Canada Gazette Pt III contains acts of parliament more or less immediately after they receive Royal Assent

- Gazette Pt III, 1998+

- Gazette 1841-1997: follow instruction in “Searching the Canada Gazette” dropdown to limit results

Annual regulations are not available from Justice Laws. Find these in the Gazette. Part I contains notices and proposed regulations, while Part II contains regulations and other statutory instruments

Ontario: E-Laws

E-laws provides an official source of Ontario statutes and regulations.

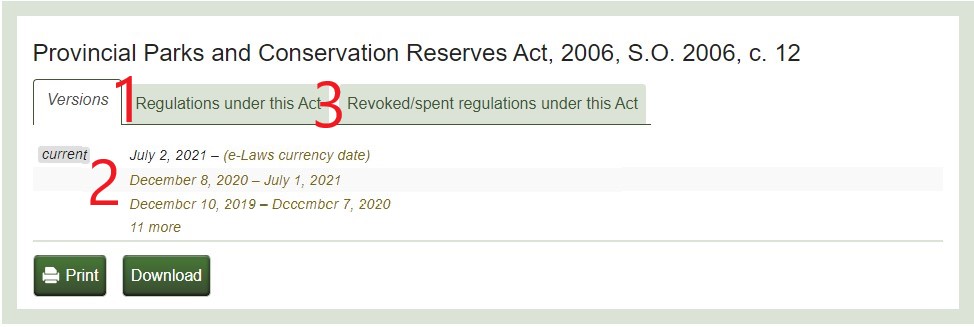

To work with consolidated law, it is usually easiest to browse to the statute you’re interested in. Once there, the top of the page has a wealth of useful information:

- Consolidated versions of regulations made under the authority of the act are all grouped in this tab, organized in reverse chronological order (newest first) from when each regulation was originally made (not date of last amendment).

- “Versions” provide point/period in time access to older versions of the legislation, as a new version is created every time the act is amended. Versions are available for amendments going back to January 2, 2004.

- “Revoked/spent regulations under this Act” is probably the least useful part of the page, but nonetheless has value, as it allows you to see no longer in force regulations that belonged to the act.

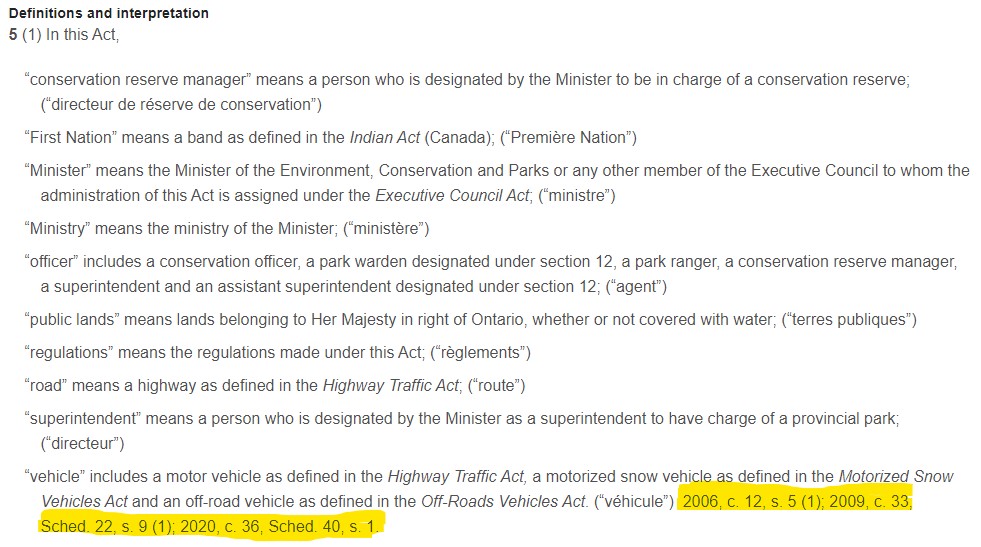

This example shows that the current version of subsection 5(1) of the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act originated in SO 2006, c 12, s 5(1), and that it has been amended in some way twice, by SO 2009, c 33, Sched 22, s 9(1) and by SO 2020, c 36, Sched 40, s 1. You would have to look at these amending acts in Source Law to see what each one does (add, amend, revoke language).

As well, you may see greyed out text in consolidated legislation. This can indicate original OR amended/new material that is not yet in force.

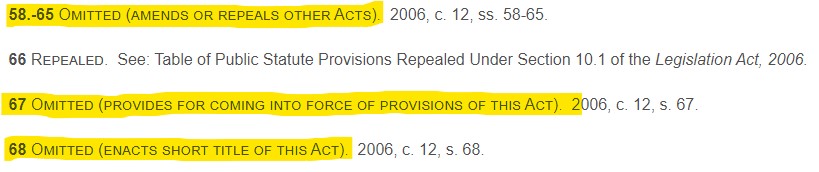

What isn’t included in consolidated law are sections that deal with how the act came into force, and consequential amendments to other acts:

To read this information, you’ll need to move from the consolidated law section of E-laws, to source law.

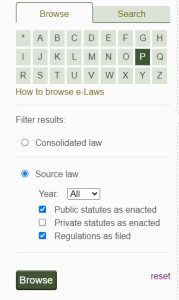

Source Law

Source Law is where you will find “as passed” (acts: annual statutes) or “as made/filed” (regulations) legislation, from 2000 forwards, and are best accessed by browsing to the year when the act/regulation of interest was passed/made. These versions do not include later amendments, but do include in force and consequential amendment sections.

Hansard

Hansard or “the debates” are verbatim transcripts of discussions in legislative bodies. They can help you determine the legislative intent behind an act or amendment. As discussed below, bills are debated in legislative bodies as part of the process of becoming statutes.

Ontario Hansard are available online since October 1975 at https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/house-documents OR http://hansardindex.ontla.on.ca/. Older debates are available in print at various law libraries from 1954 onwards (older debates are what is called the “scrapbook debates.” Talk to a law librarian if you need to go back this far).

Federal Hansard is available online since Confederation.

- The easiest to use source, which covers 1994 to 2004, includes an index: 1994-2004 https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/35-1/house/hansard-index.

- Unindexed debates are also available from 1994 to current: https://www.ourcommons.ca/PublicationSearch/en/?PubType=37.

- From 1867-1994, digitized debates are available at http://parl.canadiana.ca/browse?show=12. Use the index volume for each session to find page numbers for relevant material, as “search within” works poorly or not at all (due to the limitations of Optical Character Recognition).

Legislative Process

Why is understanding the legislative process important? Knowing how legislation progresses through a legislative body helps you understand the likelihood of a proposed change actually being successful, and prepare for changes before they happen.

Before an act is an act, it’s a bill. Read the “Bills” section of the Ontario Legislative Assembly FAQ to learn about types of Ontario bills. Learn about types of Federal bills from the LegisInfo FAQ.

- Find Ontario bills, 1995+: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/current

- Find Federal bills, 1994+: https://www.parl.ca/legisinfo/Home.aspx?ParliamentSession=42-1

Older Ontario and Federal bills are available in print from most law libraries.

Bills progress through a legislative body via a series of three readings. At first reading, a bill is introduced, and will receive first reading as long as it is in the correct format. At second reading, the bill will be justified with a speech from the sponsoring legislator (MPP or MP), and then be debated by members of the legislative body, followed by a vote. If the vote is successful, usually the bill will be sent to a committee, where it is likely to be discussed clause by clause by a committee interested in the subject the bill addresses.

- Ontario committees 1990+: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/committees

- Federal committees: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Committees/en/List

Upon return from committee, the bill will be read a third time, usually with little or no debate, before being voted on a final time.

At this point, an Ontario bill has completed the legislative process. However, the Federal system is a bicameral system. Bills can be introduced in either the House of Commons or the Senate, and after going through three readings in the first body, then has to go to the other body and repeat the process.

- Read more about the Ontario legislative process (“How do bills become law?“)

- Read more about the Federal legislative process (“How does a bill become law?“)

At this point, the bill is still a bill, not an act. The bill graduates to act status, and receives a statute number (ie Bill 15 becomes SO 1994, c 1) upon Royal Assent (“RA”). Royal assent is “in the name of the Queen” (for now), and is granted by the Lieutenant Governor in Ontario, and the Governor General at the Federal level.

Do all bills actually make it through the legislative process? No. In fact, many if not most bills (especially private member’s bills) “die on the order paper” when a legislative session is proroged/ended. Some bills, mainly government bills, are resuscitated in the next session, at the same stage (and sometimes even with the same bill number) where they previously died.

If a bill has made it all the way through the legislative process, received RA, and been assigned a chapter number, is it necessarily the law that must be followed? No! An act has to “come into force” before it has force or effect. Look at the end of the act (usually), to find out how it comes into force. Note, omnibus bills (bills that create or amend many acts) often have in-force information at the end of individual schedules. Coming into force can happen in a number of ways:

- On Royal Assent: the date on which the act received RA.

- Deemed date: “This act comes into force December 31, 2021.”

- Might be dependent on something else: “This act comes into force sixty days after the coming into force of section 15 of An Act to Amend Another Act, SO 2021, c 5.”

- On proclamation: “This act comes into force on proclamation.” It is impossible to predict when proclamations will happen. Proclamations are published in a jurisdiction’s Gazette, and can appear shortly after Royal Assent, or never.

- Federal: consult the Table of Public Statutes and Responsible Ministers. Look for your act (by name of original or amended act, not the amending act) in the alphabetized list, then look at the end of the act’s entries for the “CIF” (coming into force) information for both the original act (if post-dating the 1985 revision)and all of its amending acts.

- Ontario: Table of Proclamations

- Retroactive: Usually retroactive in force dates are only for acts related to financial issues (especially taxation), to cover a complete fiscal year.

- Some combination of above: in force dates can cover a whole act… or sections (or subsections!). So, some sections might be in force on RA, other sections might require proclamation, and other sections again have a deemed in force date.

- Talk to a librarian! Coming into force information can be complex and complicated. Get help to either verify your research, or be guided through the research process.

What about regulations? As subordinate legislation, regulations are not debated. However, you may be able to find a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement or Proposed Regulation in the Canada Gazette and calls for comment on proposed regulations (Federal), or in the Regulatory Registry (Ontario). Regulations are in force on filing unless otherwise specified.

Legislative Histories

Completing a legislative history can have a variety of goals. Sometimes, you simply want to know when a change to a section of an act was made, or when current language originated. This is often in pursuit of determining legislative intent, usually for the purposes of statutory interpretation, by then going to look at the debates around the adoption of that language. Other times, you may wish to trace the entire history of a particular act or section since its inception, to see how it evolved, and when each change to it was made (and perhaps, why).

The process of working through a legislative history can range from simple and easy (section of an Ontario act introduced last year) to the deeply complex (pre-Confederation Federal legislation, which might have originated in England). Therefore, while I’m going to set out the basic process, and point to some useful tools, this is definitely a task where getting help is likely to be a real time and frustration saver.

At its most basic level, assuming we are tracing back one section of an act to its inception, a legislative history involves following predecessor sections back until one of two things happens: At certain points in the past, legislative bodies were kind enough to include the notation New as a pseudo-predecessor section on new sections or clauses. In the absence of this incredibly helpful notation, look for a) no predecessor section information on the section you’re interested in and b) no repeal of an act or sections of an act that deals with similar material (usually found at the end of the amending act).

- If you’re tracing a section back before the current revisions (Federal: 1985, Ontario: 1990), expect the section number to change. Revisions, which used to be a regular occurrence, would usually result in renumbering of acts.

- If you think you’ve tracing a section back as far as possible, but you’re in a revision? Keep looking! There is nothing new in a revision, so it had to originate somewhere else. Talk to a librarian at this point.

- Don’t be shocked to see legislation go back to before the 1900s, or even to Confederation (1867), or beyond.

Once you’re back as far as you need to go, determine the bill number for your originating act. In both Ontario and Federal annual statutes volumes, the Table of Contents at the start of each annual volume (or in the annual statutes section of Justice Laws and E-laws) includes not just a list of the acts in the volume, but also their bill numbers, which is super handy. The reason you need the bill number, rather than just the chapter number of the act, is that it’s as a bill that the legislation will make its way through the legislative process, and so that’s how it will appear in the index of the debates. Also note the year that act was made, as you’ll have to map the year of the annual volume to the parliament and session, as that’s how the debates are organized (one calendar year can be split over multiple parliaments/sessions, and one parliament/session can encompass multiple years). Every session starts with a new Bill 1, so knowing the date is essential!

At this point, for a simple legislative history, you have enough information to trace the bill that created your act through the legislative process, and find the debates around it. If any of this information isn’t findable, or the process becomes more complex, come talk to a librarian.

How (Not) To Search Caselaw

Training from vendors (Lexis+ and Westlaw Edge Canada) encourages keyword searching from database homepages. Unfortunately, this really is the least efficient, and most frustrating way to work with caselaw. Why is this? The primary reason is that legal arguments are about legal issues, and are not merely fact-driven: Keywords tend to be fact- and situation-focused, and therefore can result in missing out on leading cases relevant to the legal issues at play, but that differ on the facts (while simultaneously drowning you in hundreds or thousands of irrelevant cases).

There are better ways!

Firstly, start with legislation… Is your research pursuant to an act or regulation? If so, find cases that specifically deal with that legislation by noting it up.

Next, or if you’re looking at an area of law not controlled by legislation, all the tools we’ve already discussed (textbooks, articles, CLE/CPD) are likely to contain citations to cases that are highly relevant to the legal issues at hand. Once you have found even one case that is relevant to the issues at hand, you can do what I call “working a case forwards and backwards:”

- Work it backwards: What cases does your starting case cite? Focus on the paragraph(s) that deal with the topic(s) most of interest to you. What cases does the judge refer to in their reasoning process? Beyond caselaw, are there articles/reports/texts cited by the judge? Make a list (part of your research plan) of all the items that seems to be useful.

- Work it forwards: Note up your case (QuickCITE [Lexis+], Keycite [Westlaw]). Use filters to see what cases have cited the case, by depth of treatment, jurisdiction, etc. Make a list of cases that seem promising.

Still need a starting point? Browse, don’t search. Use tools like the Canada Digest (Lexis+) or the Canadian Abridgement (Westlaw). Both of these tools are digests (summaries) of cases classified by topic. This classification can be quite detailed and multileveled, which allows you to browse to a very specific legal topic to see relevant cases. It’s also good to know that the Canadian Abridgement is linked from the Canadian Encyclopedic Digest, allowing you to go directly from reading about a legal topic, to reading case digests on the topic.

Criminal trial level decisions/jury trials

When we think of caselaw, what is actually reported are the reasons… Why the judge or decider made the decision that they made. Juries do not give reasons, just a verdict, and their deliberations are confidential. Therefore, jury trials are not reported, because there quite literally is nothing to report (although there may be related decisions that are reported, such as reasons for sentencing).

As well, trial level decisions in criminal cases, generally, are not necessarily reported, as even judges are not required to issue (written) reasons, so when looking at the history of a criminal case, do not be surprised if the trial decision isn’t available.

Quebec Decisions

Many Quebec decisions are reported in French, as that is the language in which they were decided. Generally speaking, there is no comprehensive project to translate these decisions into English (Supreme Court of Canada decisions are the only decisions that you should always expect to find in both official languages). That being said, the Centre de traduction et de terminologie juridiques has begun a project “Translation of Important Unilingual Court Decisions in the Other Official Language”. Currently, this project focuses primarily on the areas of criminal law and family law.

Noting up cases

“Noting up” is the process of establishing whether a case is still “good law” for the legal principle that we’re interested in. This takes two primary forms. Firstly, we need to determine the appeal status of the case in question: if it’s a really recent case, could an appeal be pending? If so, you will need to check back later, after the time limit allowed for launching an appeal has expired. If the case is older, has it been appealed, and if so, was it overturned on appeal? Even if you do find out that the case has been overturned, you should still give the appeal decision a good close read. It’s not uncommon for cases to deal with multiple issues, and the case may have been overturned on an issue other than what you’re concerned with. Secondly, and this is the more complex process, we need to look at whether our case has been “judicially considered” by subsequent cases. This consideration can be as simple as merely citing our case within a long string of similar cases, or as complex as interpreting our case, applying it, or even disagreeing with it.

Noting up a case is important because most of Canada follows common law principles, which means we use the principle of stare decisis, “to stand by things decided.” Judges look to past cases that deal with similar legal issues for guidance on how to treat the case before them. This creates a legal system that’s both predictable, but that also allows the state of the law to gradually shift.

This is important to our research for a number of reasons: Firstly, and most legally significant, sufficient negative subsequent interpretation can lead to a case being no longer considered “good law.” Secondly, cases that cite your case may be dealing with similar issues… This is a good way to advance your research.

If you want to use a case to argue a point, or try to convince a judge to follow it, it’s very important to look at where the case comes from. Cases with precedential value can either be binding or persuasive. A binding case comes from a higher court in the same jurisdiction, or from the Supreme Court of Canada, and it must be followed if on a sufficiently similar point of law. A persuasive case will originate from other jurisdictions, or from a court within the same jurisdiction at the same or lower level, and a judge can be persuaded to follow it… or not.

Also important is that cases heard by a panel of judges, such as at the Court of Appeal or SCC can contain a “dissent,” where a judge can write a differing opinion to that which the majority of the court held. This is NOT binding, so be careful when reading long appeal cases… “Ctrl+F” can easily pull you into a dissent without knowing it. Now, just because you find useful material in the dissent, doesn’t mean you have to discount it, as it can be persuasive, just that you need to be aware that’s what you’re looking at.

Tools for Specific Tasks

Words and Phrases

Collected and edited judicial definitions of words or phrases… like a dictionary but for legal definitions. Sometimes these are not the same as general definitions! There are versions on both Westlaw Edge Canada and Lexis+.

- How to find words and phrases that have been judicially defined (Video from Thomson Reuters/Westlaw)

Forms & Precedents

These are documents drafted by experts that serve as a starting point for your work. Examples include contracts, leases, licensing agreements, and cohabitation agreements. Some are mandated by legislation (court forms), but most are not. Generally, forms and precedents are more “fill in the blank” than “filled in.”

Use them when you need to draft a form, instead of drafting from scratch. They will help you save time, and ensure you cover essentials. Usually, it’s not feasible to simply take a form and use it “as is.” Use them for inspiration or confirmation, and by combining clauses from multiple forms.

Find forms and precedents in major, broad scope sets: O’Briens (on Westlaw and in print), Canadian Forms and Precedents (on Lexis+ and in print). Also consider topical collections: Find these by searching a library catalogue for general area of law + “forms.” Many topical textbooks also contain some forms, and CPD/CLE are excellent for new and notable topics.

News/Opinion/Statistics

Research for legal purposes can expand far beyond what we usually think of as “legal sources,” to include news media, statistical information, social media, and older versions of websites. While hardly an exhaustive list, I’ve pulled together some tips for searching beyond legal resources.

News and Editorial Content

You may need to search current or historical news coverage, to gauge public opinion, find more useful information about a casually mentioned case, or gather information about a person, company, or other organization. Think about the language you use for searching… Journalists writing for a popular audience are not likely to use highly “legal” language, so think of terms that would be recognizable to a lay audience.

Leddy Library subscribes to a wide range of databases that cover local, national, and foreign newspapers. For current news coverage, Google News is a fast, free source that covers a broad range of news sources, although not to the historical depth of subscription databases. As well, limitations on access (articles per month, etc) are still determined by each individual source, not Google News.

One particularly useful site for editorial/opinion content is The Conversation, where experts and academics write for a broad audience. In addition to a Canadian version, The Conversation is also available for a range of other jurisdictions, including the US, the UK, and pan-Africa.

Statistics

Statistics Canada is always the best place to look for any statistics focused on the Canadian population. StatsCan collections encompass a huge range of crime and justice statistics, which are a likely place to start your research. Do be aware that Canada has historically been reluctant to collect race-based statistics (with occasional exceptions around Indigenous populations). Therefore, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to find detailed information stratified by race.

If you need access to statistical data to perform your own analysis, rather than reading existing reports, contact the Academic Data Centre for assistance.

Social Media

Searching social media is always a challenge, especially as more people (wisely) lock down their privacy settings. That being said, search engines focused on social media, such as Social Searcher, do exist. However, this is one place where absence of evidence/content, is not evidence of absence (of content): Social media posts, especially of a dubious quality, are often deleted. However, the next tool might just help you find even a deleted tweet…

Wayback Machine

The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine is my secret weapon… Have a citation to a webpage that’s disappeared or changed? Need to see what an organization was saying about itself ten years ago? Looking for the aforementioned deleted tweets?

The Wayback Machine collects and archives copies of many (but certainly not all) websites on a regular or semi-regular basis. While there certainly is no guarantee that the website you need was archived at the date you require, it is a quick and easy place to look. Just enter the URL that you’re interested in, in the search bar. If the site was archived at any point, you will be able to browse through a timeline and calendar of all the dates it was archived. Other tools allow you to compare various captures of a site, but the calendar is by far the most useful tool. Media embedded on a site, such as videos, Flash, and sometimes even linked documents such as pdfs are not always captured, but the Wayback Machine still is the single best tool to put truth to the aphorism that “nothing disappears from the internet.”

Quantum services

Quantum services are tools to help you (more) easily determine the amount of something (personal injury damages, criminal sentencing, child support etc). They tend to be focused on one specific topic. In format, quantum tools are numbers-based, but usually have some accompanying explanatory text including key factors that influence the number. Some quantum tools allow your input, others just allow you to browse and read. They are the best choice when “the answer” is a number: Searching for “how much”/“how long” is not efficient.

There are a range of quantum services on Lexis+ (video) and Westlaw Edge Canada (video on Litigator quantum services, but also see How to find digests of sentencing quantum decisions).

How you use a given quantum service depends on its arrangement. Many quantum services are browsable via “tree” structure, which allows you to drill down through relevant “+” menus and then scan for key information in case digests. Others are accessed via a fillable form, where you can input all relevant information (that you have available), and then get a specific result/number, accompanied by supporting case digests.

Municipal Material

Municipal governments are the third level of government that affect our lives (the others being federal and provincial). In many ways, municipal bylaws have some of the greatest effect on how we live our day to day life… Where can we park? What pets can we have? How tall can we build a fence? Yet, municipal government information is usually the most difficult to find.

There is no central repository within Ontario for municipal bylaws. Each municipality maintains their own bylaws. Happily, in contrast to even a decade ago, most municipalities do now put a current consolidation of at least some of their bylaws online, and the larger the municipality, the more tends to be online. Less happily, if you need to see what a bylaw looked like before a newer amendment (IE point in time) or a bylaw that hasn’t been made available online, you will have to contact the municipality and request it. Generally these requests are fulfilled, but not necessarily in a particularly timely manner.

Council proceedings are not nearly as accessible as equivalent material from the federal or provincial government. Even the largest cities typically do not produce transcripts (IE easily searchable text). Agendas, and sometimes minutes and reports are likely to be available, often for at least a few years, and can help you narrow down dates on which a topic was discussed, and perhaps who was involved in the discussion. Some municipalities broadcast their council meetings, either through local cable, or online, and sometimes there are archives of past recordings of these broadcasts. However, this is very much on a municipality by municipality basis.

Indeed, this is the overarching theme of researching municipal materials and processes… The information available, and the means by which you can access that information, are wholly dependent on each municipality in question. Often, the only thing you can do is essentially throw yourself on the mercy of a municipal clerk, and hope that they have access to, knowledge of, and a willingness to share the information you need.

Blogs, Firm Websites, and Other Sources

These are another example of sources that would typically not be used at all in academic research, but can be quite useful in practical research. They are especially useful for researching novel or fast-evolving areas of law. You will have to be quite discerning in order to evaluate the quality of the information in these sources. Think about the CRAAP test:

- Currency: Look for a date on the source. Do you know that there’s been a significant amendment to legislation, or major case since this date? It might no longer be accurate.

- Relevance: In terms of legal research, replace this with jurisdiction. Is this author/source originating in/writing about Canadian or Ontario law (as applicable)? The law of child support in Ontario, California won’t be relevant to research about support in Ontario, Canada!

- Authority: Who wrote the material, and where is it hosted? If you can’t tell, do not use this source. On the other hand, if it’s written by lead counsel in a significant recent case, and hosted on the site of a major Canadian law firm, this is more likely to be good quality.

- Accuracy: At the most basic level, is it well written? I would be dubious about a source that has many egregious grammar mistakes. In terms of legal research, this also encompasses accurate and correct citations to cases and legislation. Does the information that this source is trying to impart to you, fit with what you already know?

- Purpose: Are you being sold something? Or propagandized? What audience is the information intended for? Laypeople or legal professionals?

Where Can I Find Help?

Librarians and libraries will accompany you throughout your legal career. The practice of law is the practice of information; finding it, interpreting it, synthesizing it, and conveying it to other people. Therefore, expert information workers, in the form of librarians, are always here to help.

In addition to reaching out to the staff of the university law library, every courthouse in Ontario has a library (of various sizes), and if you’re working with/for a member of the Law Society of Ontario, you’ll also have access to the vast array of resources and expertise at the Great Library.

Never hesitate to reach out to a librarian, at any phase of the research process. We can help you devise a research plan, ensure you haven’t missed anything in your search, or help you with challenging tasks, such as legislative histories. Also, don’t worry about asking a “non law” question… If we don’t know the answer, we have subject expert contacts that we can rely on to get you the help you need.

How Do I Know I’m “Done?”

It can be really difficult to determine when your research is complete, especially when you’ve been asked to do a really deep examination of a topic. This is where your research plan comes back in: Is every source you’re looking at telling you something you already know? Perhaps more importantly, do you feel like you’re going in circles, because regardless of what source/technique you use, you end up back at the same information/cases? This is a pretty reliable sign that you either need to take a dramatically different tack in your research (which may not be relevant), or that you have truly canvassed the area of examination.