PORTRAITURE

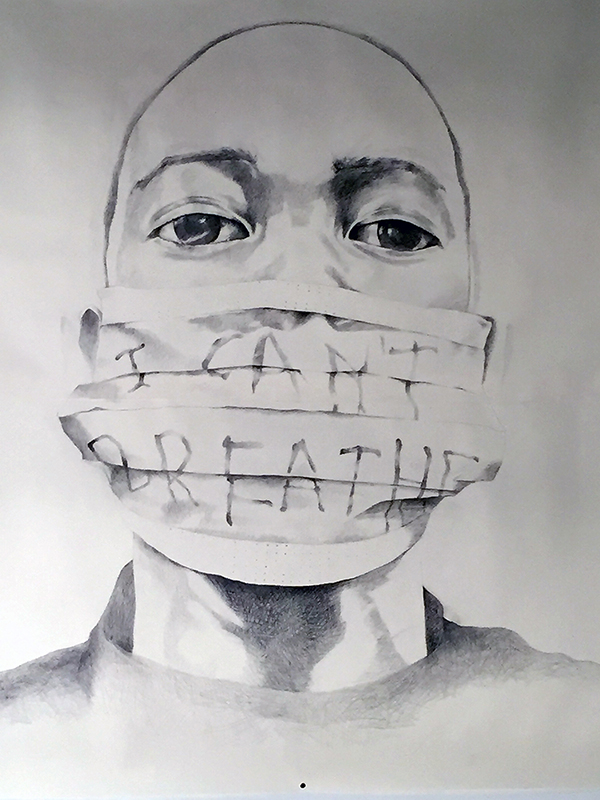

“I can’t breathe.” After months of wearing masks to protect ourselves and others amid the coronavirus pandemic, the image of a protester with their face partially covered might seem unremarkable. However, here “I can’t breathe” does not refer to a resistance to mask mandates; rather, these are the last words of Eric Garner, a Black New Yorker killed by police in 2014 after they placed him in an illegal chokehold while attempting to arrest him. The killing of Garner led to widespread protests across the United States, including a December 20th protest at the Mall of America where Taui Green, the activist depicted here, demanded justice for Garner.

Their Borders Crossed Us: For Eric comes from Toronto-based artist and community activist Syrus Marcus Ware’s Activist Portrait Series, a collection of works that capture—on a larger-than-life scale—the faces and figures of those working to effect change for their communities. Ware’s series focuses on activists from marginalized communities, and includes depictions of trans, queer, and disability-rights activists, as well as founding members of Black Lives Matter – Toronto. In creating portraits on a massive scale, Ware tackles an artistic tradition that has typically been used in the West to glorify royalty, military leaders, celebrities, and politicians. Ware instead uses it to celebrate the grassroots work of individuals who often go unacknowledged in the press, and whose names are rarely known among those who benefit from their work. In doing so, Ware highlights the commitment and potentially outsized influence of these individuals, their work contributing to building a better, more just world. As he states,

By using the methods and modes of painting and portraiture, community—specifically Black, Indigenous, Queer and Trans, the disability community—is documented as a lived reality and painted into art history. Lives are rendered visible through this large format and use of a style and medium previously reserved for dignitaries and wealthy patrons. The artistic tradition of painting is impacted by re-enforcing systemic structures such as class hierarchies, racism, and defining which humans are valuable. This body of work attempts to interrupt this process by re-entering the frame around “unintelligible bodies” —those on the margins (Ware 2021).

Ware’s activist series thus engages with the history of portraiture in Western art in a manner that both upends it and reinforces its value.

Watch the video below to learn more about Ware’s process for making the works in his Activist Portrait Series.

Portraits are works of art that contain a representation of an individual. They can be carved or painted, rendered through photography or collage; they can be abstract or realistic, and may serve as official documents or touchstones for precious memories. Today in Canada (as elsewhere), we are surrounded by portraits; they fill our phones and our wallets, clutter our news feeds and social media, reminding us of who we are, and also who we might be. However, the ubiquitous nature of the portrait in Canadian society is a relatively recent phenomenon given the history of the genre. While portraiture has been central to many artistic traditions across cultures and centuries, in the West it has often been used to connote money and power, and to identify those who possess it.

In this context, portraits were typically commissioned by wealthy individuals as a means to convey their status, occupation, or position in society. As a result, many historical portraits feature representations of the aristocracy and successful merchants, as well as celebrities such as writers and performers. They are less likely to depict the working classes, enslaved people, or those without claim to notability through either status or occupation. In recent years, contemporary artists have challenged the absence of these communities and populations in portraiture by deliberately inserting neglected or unrepresented groups into their work. A now well-known example of this is the African-American artist, Kehinde Wiley, who appropriates imagery from historical portraits of notable figures and replaces these figures with ordinary Black individuals, selected through a process Wiley describes as “street casting.” In altering these historical works, Wiley draws attention to the absence of Black people in Western portraiture. Like Ware, he both affirms and critiques the power of the portrait. Other artists working in the Canadian context have also created works in this vein. The historical portraits created by Zacharie Vincent and the contemporary photography of Jeff Thomas both focus on the representation of Indigenous individuals, again drawing attention to the omissions and elisions in the history of portraiture.

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.1

Take a moment to note the portraits you have seen today. Whom do they depict? Where are they? Consider whether these portraits were produced for particular purposes or placed in significant locations. How do you think they are intended to be viewed? What power dynamics are evident when you think about these portraits in this way?

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- consider the “double presence” of portraits and how both artist and sitter might be agents in a work’s creation

- recognize portraits not as straightforward likenesses of individuals, but as objects caught within systems of signification

- critically analyze portraits, including by “reading against the grain”

- articulate how portraiture engages with issues of representation—who is represented and how.

It should take you:

Their Borders Crossed Us Text 10 min, Video 3 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

From absence to presence Text 30 min, Video 4 min

Seeing as self-determination Text 20 min, Video 5 min

Affirming existence Text 17 min, Video 19 min, Audio 4 min

Learning journals 6 x 20 min = 240 min

Total: approximately 6 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 5.1 Syrus Marcus Ware, Their Borders Crossed Us: For Eric (2015)

- Fig. 5.2 François Malépart de Beaucourt, Portrait of a Haitian Woman (1786)

- Fig. 5.3 François Fleischbein, Portrait of Betsy (c. 1837)

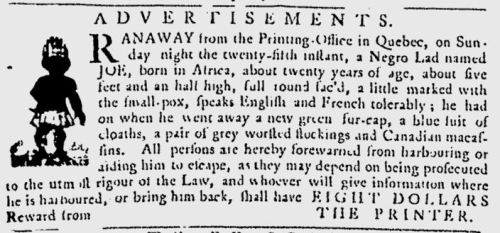

- Fig. 5.4 “Advertisement,” Quebec Gazette, January 29, 1778

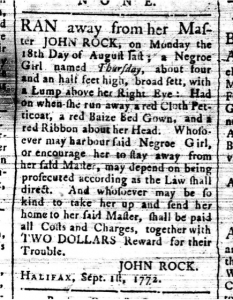

- Fig. 5.5 John Rock, “Advertisement,” Nova-Scotia Gazette and Weekly Chronicle, September 1, 1772

- Fig. 5.6 Prudence Heward, Hester (1937)

- Fig. 5.7 Image of Dorothy Stevens’s Coloured Nude (1932)

- Fig. 5.8 Prudence Heward, At the Theatre (1928)

- Fig. 5.9 Zacharie Vincent, Self-portrait, n.d. (before 1878)

- Fig. 5.10 Wampum belt (Eastern Woodlands) (18th or 19th century)

- Fig. 5.11 Annular brooch (Eastern Woodlands) (18th or 19th century)

- Fig. 5.12 Ceinture fléchée perlée (Huron-Wendat) (1825-75)

- Fig. 5.13 Cornelius Krieghoff, Moccasin Seller Crossing the St. Lawrence at Quebec City (c. 1853-63)

- Fig. 5.14 Judith Leyster, Self-portrait (c. 1630)

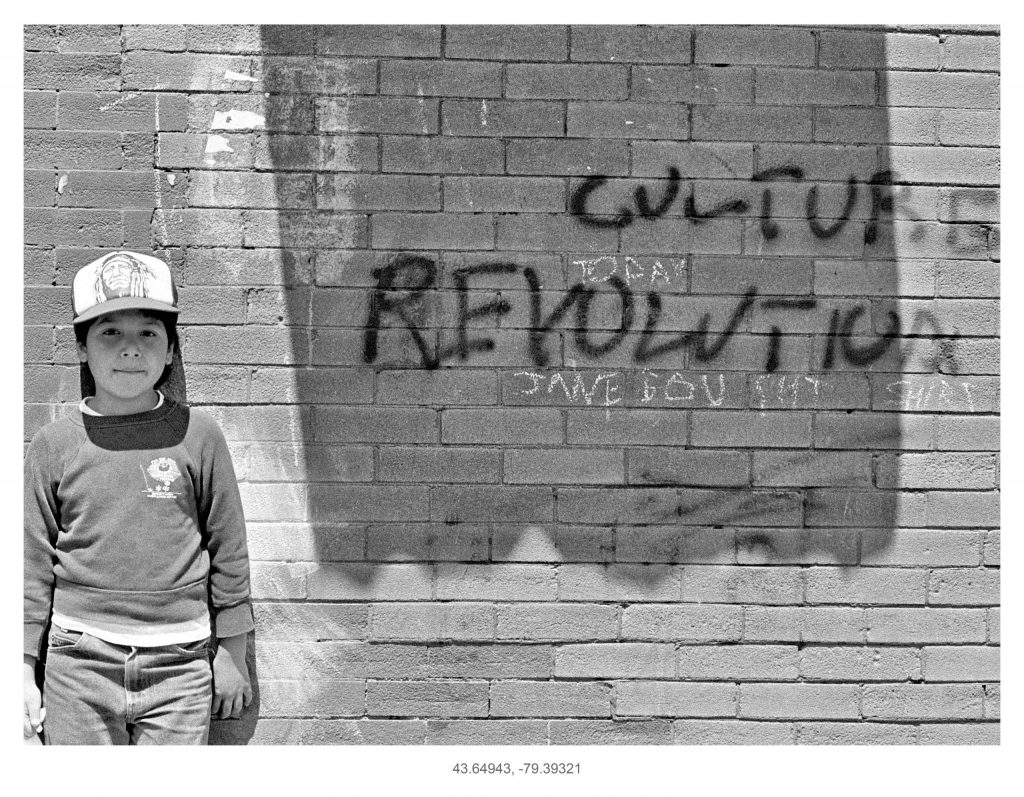

- Fig. 5.15 Jeff Thomas, The Bear Portraits: Cultural Revolution (1984)

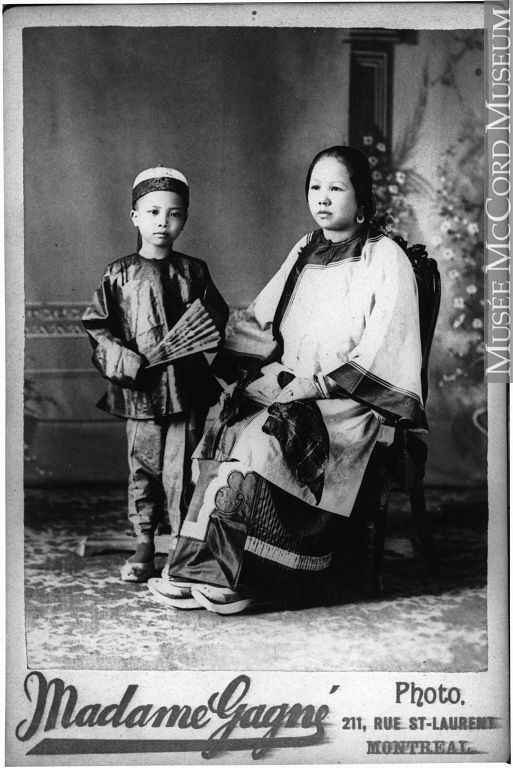

- Fig. 5.16 Madame Gagné, Mrs. Wing Sing and Son, Montreal, QC (1890-95)

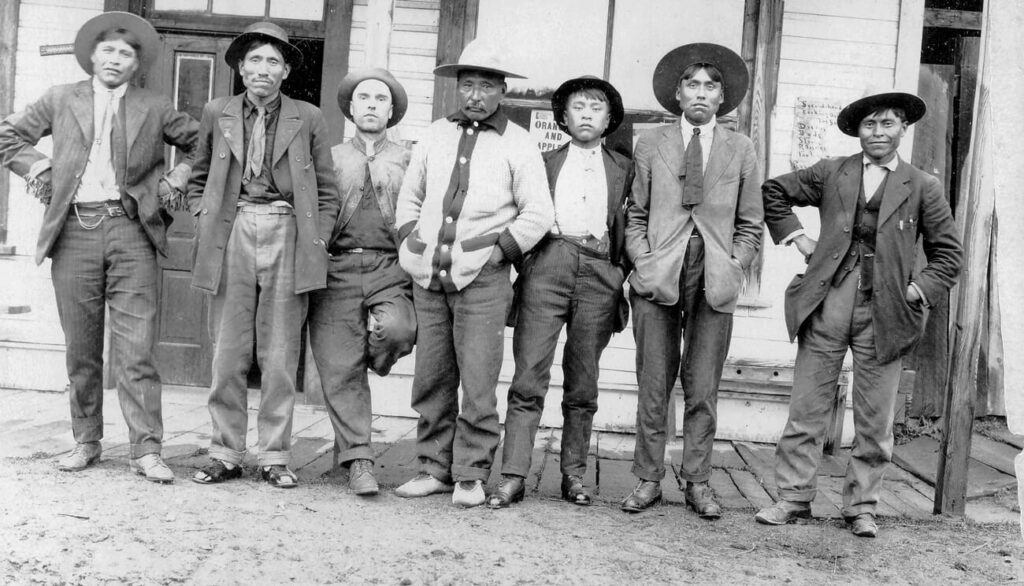

- Fig. 5.17 C.D. Hoy, Group of men in front of C.D. Hoy’s store in Quesnel, British Columbia (c. 1910)

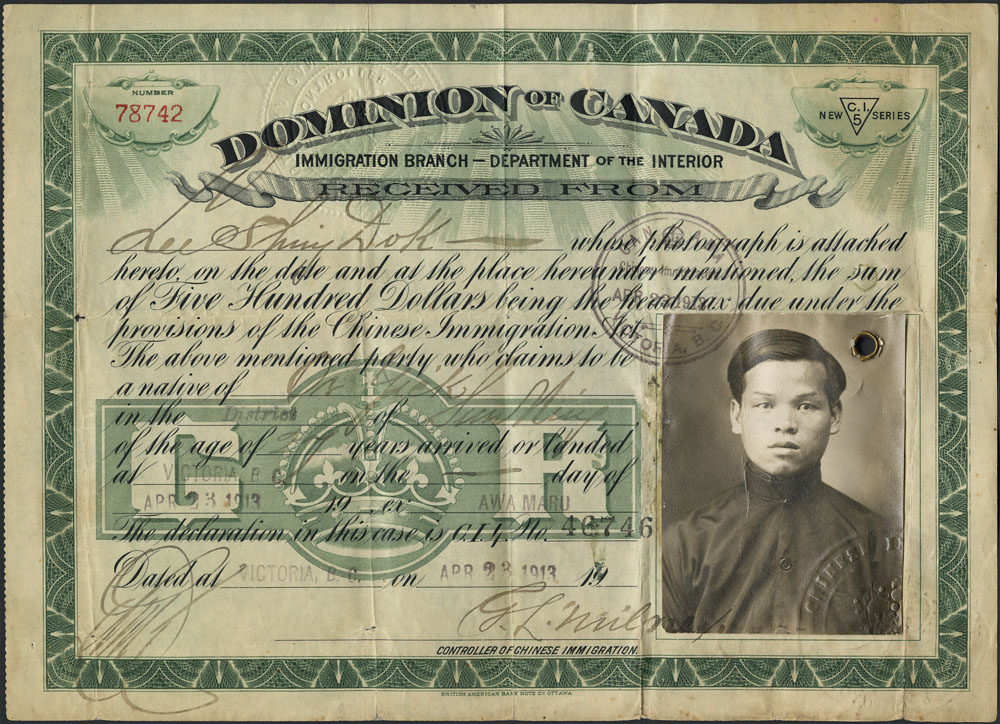

- Fig. 5.18 Chinese immigration certificate (1913)

From absence to presence

Typically, when art historians think about the identities of individuals associated with works of art, they focus on the artist. However, in the study of portraiture, the focus is somewhat different. In this case, researchers focus on the individual depicted in addition to the artist; sometimes the sitter is even seen as more important than the artist who executed the portrait. This is what art historian Lara Perry calls a portrait’s “doubled presence.” She writes, “Any portrait is a documentation of at least two historical events: the presence of the sitter, and the work of the artist. A portrait, consequently, has two agents, and a doubled presence. While both agents (sitter and artist) might be held mutually responsible for the finished object, more commonly one agent is privileged as the producer of the image” (Perry 2001, 117).

For Perry, this is a useful way of thinking about portraiture because it allows us to consider the creative contributions of those depicted, and how they might have sought to control their own image. Women, for example, often modelled for portraits, but were less frequently the authors of them, and thus they had fewer opportunities to determine the works’ final aesthetics and the translations of their likenesses. Although focusing on the individual depicted rather than the artist does not address the absence of some communities from historical portraiture, it does offer art historians an opportunity to consider and recognize the aesthetic contributions of those depicted, and whose role in the creation of the artwork has rarely been privileged.

This module explores these themes through a consideration of portraiture in the Canadian context, focusing not only on who is depicted, but how. It further investigates the significance of these choices, and how something as seemingly ordinary and conventional as a portrait can not only challenge artistic conventions, but also how we understand ourselves and Canadian society.

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.2

Watch “What is the difference between a selfie and a self-portrait?” Then, choose a recent photo that you consider to be a good representation of yourself (this image doesn’t need to contain a person) and write a short paragraph (4-5 sentences) describing why you think this is the case. Make sure to draw upon specific visual details in your answer. Would you categorize this image as a self-portrait or a selfie? Why?

This portrait by French-Canadian artist François Malépart de Beaucourt was previously titled Portrait of a Negro Slave or Portrait of a Negress; it was likely created while Beaucourt was living in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, the region currently known as Haiti. Although enslaved individuals do appear in several group portraits in the European tradition, often as indications of a family’s wealth and status, portraits of individual enslaved people are unusual. As Marcia Pointon notes, because portraits are predicated on the existence of an autonomous individual and slavery, by its very nature, transformed people into objects and property, a portrait of an enslaved person is almost a contradiction. As she asks, “if the slave officially has no identity, how can he or she be configured in a genre, the languages of which were coined to bespeak individuality?” (Pointon 2013, 62).

Recent research by art historian Charmaine Nelson suggests that the sitter is most likely fifteen-year-old Marie-Thérèse Zémire, one of several enslaved women and girls owned by Beaucourt’s wife, Benoite, during her lifetime, and who was removed from Saint-Domingue to Montreal by Beaucourt and his wife as they fled the tensions that would eventually lead to the Haitian Revolution (Nelson 2015). While settlers in Canada did not rely on slavery to the same extent as their American counterparts, slavery was a relatively common source of domestic labour in aristocratic, professional, and merchant households until the 1834 implementation of the law abolishing slavery across the British Empire. In the mid-18th century, for instance, there were approximately 3,600 enslaved people living in New France (Quebec). These included Indigenous individuals as well as those of African descent, who, like Zémire, were brought to Canada via the Caribbean.

Because Zémire likely sat for this portrait at the behest of her owner, it is difficult to read the image in the same way we might read portraits commissioned by their sitters and which typically serve as a projection of how the sitter perceived their own identity. Indeed, Beaucourt’s image, and the manner in which he depicts Zémire, contains similarities to other examples of visual culture from the period. A 1791 engraving by Nicolas Ponce which features illustrations of both an enslaved and a free woman of colour in Saint-Domingue, for instance, distinguishes between the free woman of colour, or affranchie, and the enslaved woman (ésclave) through their dress. The ésclave is only semi-clothed—her breasts are bare—and she wears a plaid headwrap and carries a basket of fruit (Wilson 2021). Nelson has pointed out that the proximity between Zémire’s bare breast and the basket of fruit, often a symbol of fecundity in Western art, in Beaucourt’s painting may allude to the woman’s potential for “breeding,” a detail that would highlight her value as property; female slaves were prized for their ability to produce more slaves given that slavery was a hereditary institution (Nelson 2014). Children born to enslaved mothers, whether the product of a relationship between enslaved individuals or coercion by white slave owners, were themselves forced into slavery.

If Beaucourt’s image depicts Zémire as he, a white colonial slaveholder perceived her, is it possible to read any elements of this portrait as indications of this woman’s autonomy, of her identity as anything other than an enslaved individual? Charmaine Nelson’s attempt to name the sitter of Beaucourt’s painting offers a first step in locating this woman in history, to give her an identity, which would have been forgotten at the moment of this portrait’s creation as the work’s previous title—Portrait of a Negro Slave—suggests.

Considering the material culture within the work offers us another way to read the image. In Beaucourt’s work, Zémire is depicted wearing a red and white tignon, or headwrap, probably made of madras or similar cotton cloth. Headwraps were a common form of attire for women throughout the Caribbean, Louisiana, and the Spanish Gulf Coast in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and from at least 1779 were a mandatory article of clothing for all women of colour in Saint-Domingue, whether free or enslaved. (A similar law was enacted by Governor Esteban Miró in Spanish Louisiana in 1786.) These sumptuary laws, enacted by white, colonial governments in societies with large Black populations worked to police Black women’s bodies—Black women were regarded as sexually lascivious in comparison to their white counterparts—and maintain racial distinctions, as slavery and interracial relationships led to an increasingly creolised society. However, recent scholarship has sought to define the headwrap as more than a marker of Black women’s subordination within colonial societies. Instead, scholars such as Jonathan Michael Square and Nicole Wilson see it as a potential site of resistance.

Headwraps like the one worn by Zémire in Beaucourt’s portrait have their roots in West African cultures and formed a link between enslaved women in the Caribbean and their ancestors, despite the violent attempts of slave traders and owners to erase these connections. However, more than a link to their heritage, headwraps became a site of Black women’s creativity. Styled, knotted, wrapped, and adorned in a variety of ways, headwraps became a means for women to signal their social status, cultural heritage, or ingenuity while working within frameworks imposed by colonial governments. As Wilson writes, “By reassembling West African headwrapping traditions in the New World, women of colour were able to reassert their corporeal autonomy and demonstrate countercultural defiance in the face of a colonial infrastructure that sought to obliterate ancestral African cultural identities” (Wilson 2021, 5).

While we do not know whether Zémire was responsible for styling the headwrap in Beaucourt’s painting or whether it was an addition prompted by the artist’s engagement with visual tropes for the depiction of enslaved Caribbean women, its presence subtly alludes to a history of self-styling and a bid for autonomy in a society that otherwise stripped individuals of their identities in order to redefine them as property. Thus, much like the way Afro-Creole women used headwrapping to subvert the colonial legislation that governed their bodies and lives, the headwrap within Beaucourt’s portrait challenges the artist’s attempt to reframe Zémire as an object without a history rather than an autonomous subject.

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.3

Consider the two advertisements below.

What visual and material details can you glean from these texts? How do these details compare to what is typically represented in portraits during this period? Why do you think the descriptions are so detailed? Why might reading alternative sources against the grain be significant for the study of art history in Canada?

Portraits of specific enslaved individuals from the 18th and 19th centuries are rare. As a result, scholars have looked to other media for alternative visual depictions of enslaved people. Charmaine Nelson, for instance, has proposed that reading runaway slave advertisements “against the grain” allows them to function as a kind of visual representation. When reading against the grain, researchers attempt to move beyond the dominant reading of a text—or the most commonly accepted interpretation—to discover alternative, even resistant readings. In the North American context, this often means looking at the work from a less privileged perspective—in a way that disrupts an assumed white, male, middle-class, heterosexual, or able-bodied point of view. Because those who lack privilege—whether by virtue of their gender, race, or class—have frequently been overlooked or left out of dominant narratives, reading against the grain presents a means to address the gaps—and sometimes fill the silences—in Canadian history.

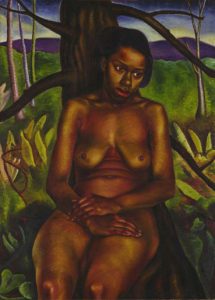

Prudence Heward’s modernist painting Hester offers a very different depiction of a Black woman. As with Beaucourt’s image of Zémire, this work plays with the conventions of portraiture. Most critically, it merges the portrait—the sitter is a named individual—with another Western artistic tradition, that of the nude, a genre that emphasizes the depiction of the unclothed human form, often within the natural landscape. At the same time, the work does not easily conform to either tradition.

Hester is stripped of many of the features used to identify individuals in conventional portraits; although her facial features are distinct, she wears no dress or accessories that might point to an occupation, social status, nor her temporal or geographic location. (Unlike Beaucourt’s model, however, Hester’s head is uncovered, revealing her natural Black hair.) Heward also avoids portraying Hester in the alluring manner typical of the female nude in Western art history. Although the woman’s figure does appear in a natural landscape, the pose is somewhat awkward—the model is slumped and her breasts sag. She might even be described as modest—Hester’s hands are delicately placed to cover her genitals. Given that the female nude was typically created for consumption by a heterosexual male audience, these differences are significant.

Prudence Heward specialized in studies of the human figure, despite the general popularity of landscape painting in Canada during the early 20th century. Many of her works focus on female subjects and this is not the only image she created that depicts a Black woman. Others include Dark Girl (1935), Negress with Sunflowers (1936), and Girl in the Window (1941). Like Beaucourt, Heward presumably hired or persuaded the model to sit for this image—rather than painting it at the sitter’s request—and it is possible that Heward completed this work, or a study for it, while visiting her artist-friend Isabel McLaughlin in Bermuda. Nevertheless, the sitter is named in the title of the work, which is not the case for Heward’s other images of Black women, suggesting a desire for an identity and image to cohere—something we do not observe in Beaucourt’s painting.

Some scholars have questioned Heward’s interest in Black, female subjects. Art historian Julia Skelly, for instance, suggests that it is unclear “[w]hether this interest was primarily formal (in that painting black women allowed her to experiment with different colours of paint), altruistic (calling attention to issues of race in Canadian society), a result of the availability of black models in early twentieth-century Montreal (many of whom worked as domestics and needed the additional money), or a combination of these factors” (Skelly 2015, 41). Certainly, Heward was invested in the avant-garde artistic movements popular in Europe in the early 20th century. In the 1920s, she studied art in London and Paris, absorbing and reinterpreting the visual language of the Fauves and Post-Impressionists, and, while working in Montreal, studied and associated with other artists influenced by European modernism, especially those concerned with the human figure, including William Brymner and Edwin Holgate (Skelly 2015, 5-8). Heward’s exploration of the Black female form in works such as Hester may have been another means of investigating the possibilities of representing the figure in art. However, as Skelly points out, Heward’s work also raises questions about the intersections of gender, race, and class in 20th-century Canadian society. More broadly, it prompts a consideration of how a subject’s race might shape their portrayal in art.

Within Western art history, the nude has traditionally been regarded as an opportunity for artists to showcase the female form for the pleasure of a presumably male, heterosexual audience. In doing so, artists employed certain conventions: the female nude was depicted in nature, emphasizing women’s perceived affinity with the natural—as opposed to the rational—world; her gaze was typically lowered, allowing the male spectator to consume her image without scrutiny; and she was frequently portrayed in allegorical guise (perhaps most famously, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, offers a nude in the guise of Venus, the Roman goddess of love) (Parker and Pollock 2013, 115-16). Such disguises further permitted audiences to innocently view the work, to consume a fantasy, rather than the baldly naked form of a woman. However, as Charmaine Nelson has pointed out, these conventions operate somewhat differently when the subject depicted is not a white woman (Nelson 1995).

Through an analysis of Dorothy Stevens’s Coloured Nude (1932), Nelson argues that the Black female nude sits on rather than in the landscape, playing “up the colonial perception of black female sexuality as beyond ‘natural’ limits” (Nelson 1995, 101-02), and openly displays her body, including her pubic hair, in an overtly sexual manner, further suggesting a perceived “animal sexuality and carnal desire” (Nelson 1995, 101).

Heward’s Hester exists between these conventions. She passively averts her gaze and does not directly address the spectator, yet her posture is closed; she covers her pubic hair and her body slumps in on itself. Similarly, sitting between portrait and nude, Hester is not disguised by fantasy; she is flesh and blood, distinguished by the colour of her skin. And, unlike Stevens’s Coloured Nude, she exists in harmony with the natural landscape—her body merges with the tree against which she sits—though it could be argued that the lush foliage in the background sets Hester apart from the Canadian context. These details draw our attention to the complex intersections of race, gender, and class, and how these factors shaped the experiences of the artist, model, and viewer. Some, for instance, reacted negatively to the work’s refusal to conform to artistic convention. As one reviewer/critic wrote in 1938, “Heward’s ‘Hester’ was far from pleasing. Why, oh why, take the trouble to paint—and paint well—a hideous, fat, naked negress, with thighs like a prize-fighter and a loose-lipped, learing [sic] face?” (R.B.F. 1938). While many praised Heward’s Black nudes, the negative and often racist responses from critics reveal that the artworks also clearly challenged viewers (Smither 2019, 90).

Why did Heward “trouble” herself with this depiction? Certainly, as a white woman artist from an established Montreal family, Heward would have occupied a very different social position to that of her model and it is possible that she saw working-class Black women as a ready source of artist models, as Skelly suggests. At the same time, as a female artist, Heward was also subject to limitations. She never married, as married women were often encouraged to abandon professional careers. In moving between artistic conventions Heward’s work defies a straightforward reading of the Black body objectified by the white, colonial gaze. Given a name, yet painted unclothed, Hester is both subject and object, a reminder of the progress made by women in Canadian society in the 20th century, as well as of the limits imposed upon those identified racially as “other.” As art historian Devon Smither writes, “Operating outside the artistic and ideological conventions that governed the representation of black women at the time, Hester offers contradictory visual elements that challenge the stereotypical representations of black women at this time” (2019, 87).

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.4

Seeing as self-determination

Figure 5.9 Zacharie Vincent, Self-portrait, n.d, before 1878. Oil on paper, 62.5 x 53 cm. Musée de la civilisation, Quebec City. Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA). Uploaded by Wikimedia user Wilfredor.

Although the paintings by Beaucourt and Heward contain the traces of portraiture’s “doubled presence,” it is likely that in both cases the depiction of the subject was largely, if not exclusively, determined by the artist. In Huron-Wendat artist Zacharie Vincent’s Self-portrait (n. d.) from the 19th century we see something different. As both creator and subject of this work, Vincent was able to determine and enact the manner of his own self-presentation. In doing so, he not only offers a powerful image of self-determination during a period of intense settlement, but the painting also reflects the complex changes occurring within Indigenous societies as a result of European colonization.

Some of these changes are reflected through the objects that adorn Vincent’s body—regalia drawn from Huron-Wendat and colonial traditions and hybrid objects which signify the meeting of these cultures—and which further mark his status as a Huron-Wendat chief. Hover over the image above to learn about the different objects in this portrait and their significance.

These objects demonstrate the adaptation of European materials—silver, glass, and iron—and insignia by the Huron-Wendat in a manner that reflects their 19th-century context, while their placement in Vincent’s self-portrait suggests a perception of Huron-Wendat chiefs like himself as the equal of and diplomatic counterpart to the British and French officials with whom they interacted.

While Vincent’s self-portrait depicts numerous objects of Indigenous artistry, it does so in a manner very different from other depictions of the period. Consider, for instance, Dutch-Canadian painter Cornelius Kreighoff’s image Moccasin Seller Crossing the St. Lawrence at Quebec City (c. 1853-63), which, as its title suggests, depicts an Indigenous woman trudging across the frozen river, perhaps hoping to sell her wares in the bustling urban centre. The bundle of moccasins affixed to her body is indicative of their role as a commodity. The Huron-Wendat relocated from the Great Lakes to Quebec at the end of the 17th century as Indigenous communities were stripped of their traditional territories, whether by treaty or by force, and earlier patterns of subsistence were disrupted. For some, artisan production, especially the production of souvenir wares, became a means for supplementing hunting and other forms of trade. Indeed, moccasins were particularly popular among 19th-century consumers, and became a fashionable form of slipper (Gaudet 2019).

Krieghoff’s painting offers a generic image of productive artistry, yet it also isolates the woman within the landscape, with only a suggestion of settlement seen in the distance, perched on the ridge behind her. In doing so, Krieghoff simultaneously configures the artisan as a member of a vanishing population, a common, if inaccurate, perception settler populations held of Indigenous populations—one which simultaneously helped to generate enthusiasm for the souvenir trade, as settlers and collectors sought to purchase Indigenous-made objects in an attempt to preserve the authentic work of a supposedly “dying” culture.

As one of the first Indigenous artists to work within the Western tradition of easel painting and to appropriate the practice of using engravings and photographs as reference images, Vincent’s use of portraiture demonstrates his fluency in Indigenous and Western visual cultures and pictorial languages—through both his choice of medium and the content. Artists’ self-portraits, which typically depict the artist at work or with the tools of their trade, have historically been used in the West as a bid for recognition and self-promotion. They demonstrate the artist’s skill, both through the image depicted and through their very existence.

For instance, in the Dutch artist Judith Leyster’s self-portrait, we see Leyster at her easel, paints and brushes in hand. On the easel is a depiction of a fiddler, indicating Leyster’s ability to produce portraits as well as other popular genre pictures of her day. At the same time, however, Leyster herself is depicted, not in her painting attire, but in fashionable dress with delicate lace cuffs and a starched collar, alluding to the nobility of her task. In portraying herself in this manner, Leyster not only advertises her abilities, but makes a bid to be taken seriously, to be recognized as a serious, professional artist.

For more on self-portraiture, watch the video below. Can you think of other ways artists might represent themselves?

Vincent’s self-portrait, then, can also be seen to participate in this tradition. As well as his oil paintings, Vincent also created jewellery and other artisanal crafts, and the objects displayed within his self-portrait work not only allude to his talent with a brush but to his abilities with leather, metal, and wood. However, as art historian Louise Vigneault suggests, Vincent’s work, through the plethora of objects displayed, can be read as a celebration of the rich artistic traditions of the Wendat and simultaneously through the use of self-portraiture as a genre. The painting thus communicates Vincent’s desire to be regarded as an artist in the Western sense of the word. Vigneault writes, “The self-portrait legitimates his social standing and differentiates him from the anonymous traditional artisan, allowing him to be recognized as an artist whose work is defined not only by technical skill but also by intellectual struggle. Despite the respected place of the artisan in Huron culture, Vincent surely sought to exchange his anonymous status—as a maker of snowshoes and jewellery—for that of a professional artist, and to mark his production as distinct from the Native arts that, although anchored in tradition, remained narrow, specialized, and at the mercy of market forces” (Vigneault 2014, 41). Like the hybrid objects depicted within Vincent’s work, his self-portrait shows him operating between worlds, adapting and borrowing from both in order to forge his identity as both an artist and a Huron-Wendat chief in the 19th century.

If settler-artists such as Kreighoff reinforced romantic depictions of the “dying Indian” which Vincent’s self-portrait directly challenge, then self-described Urban-Iroquois artist Jeff Thomas’s photographic portraits examine a more recent manifestation of this myth: the absence of representations of Indigenous peoples from Canada’s urban centres.

Cultural Revolution is the first in a photographic series known as The Bear Portraits which features Thomas’s son, Bear, in various urban or culturally significant locations. Taken on Toronto’s Queen Street in 1984 when Bear was seven years old, the image juxtaposes the youthful frame of Thomas’s young son with an aging brick wall adorned with rough graffiti, raising the spectre of a gritty city. Through Bear and the baseball cap he wears, the photograph also contrasts contemporary portraits of Indigenous individuals with historical ones; Bear’s hat features a depiction of the Cheyenne leader Two Moons, an image derived from a photograph taken by American photographer Edward S. Curtis, who is best known for an expansive series of portraits of Native Americans taken in the early 20th century.

Curtis has been criticized for intentionally romanticizing his depictions of Indigenous people, playing into stereotypes of Indigenous North Americans as stuck in the past or as members of dying civilizations in a manner that also overlooked the role of European settlers in the destruction of Indigenous lives and traditions. Curtis’s images often avoid depictions of Indigenous peoples who adapted to the cultural and social shifts wrought by colonisation. In other instances, Curtis intentionally manipulated his photographs to frame Indigenous people in a past he believed was more “real” or “authentic” than contemporary life. For example, in In a Piegan Lodge (c. 1910), Curtis or one of his assistants retouched the image to remove any indication of modern artifacts like the presence of the clock in the original image. By alluding to Curtis’s work through the placement of the hat, Thomas turns this work on its head and instead reasserts the presence of Indigenous peoples in the North American landscape through the presence of his son (who also represents the youthful next generation) despite the use of government policy and the expansionist construction of civic architecture to erase Indigenous people and landscapes. Where Curtis’s photographs relied on stereotypes of the “noble savage” and the “dying Indian,” Thomas’s images disrupt more contemporary settler stereotypes of Indigenous people—that they all live on reserves separate from modern or urban life. Further, as a series, even a somewhat spontaneous and sporadic one, Thomas’s images assert the consistency and longevity of the Iroquois presence in urban Canada. As Thomas writes of his own reaction to the work, “When I saw the print, I saw myself as a young boy and remembered the fractured relationship I had with my father. This series explores the loss of male role models by using Bear as a marker of Indian-ness in sites where it does not exist. The first Bear Portrait set in motion a new way of looking at the city and, like the graffiti, my revolution was against the invisible urban Iroquois presence” (Thomas 2021).

Watch the video below to learn more about Jeff Thomas’s artistic practice. How does it challenge settler-colonial narratives of Indigenous erasure?

Through his photography, Thomas does the looking, documenting not only urban Iroquois existence, but what the urban landscape looks like through the eyes of an Indigenous person. This use of the camera provides another powerful contrast with Curtis’s work. In The Bear Portraits, Thomas and his son become the subjects of the work, rather than the object of the photographer’s gaze, as was the case for the Indigenous sitters in Curtis’s images. This reversal is significant as it draws upon the camera as a tool for self-determination. Cultural critic Susan Sontag has argued about photography that, “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power” (Sontag 1973, 4). In photographing his son, Thomas takes ownership of the image, and of the portrayal of urban-Iroquois individuals like himself, thus reclaiming the power of the image.

At the time of their creation, Zacharie Vincent’s and Jeff Thomas’s portraits challenged settler assumptions about the presence of Indigenous people in North America and they continue to do so today. Other artists have used and continue to use portraiture to picture an Indigenous future. Read artist Lauren Crazybull’s essay “Seeing Through” to learn more.

Affirming existence

Thomas’s works combine formal portraiture with the tourist snapshot, alluding to the camera’s role in the democratization of portraiture. Developed in 1839, photography quickly grew in popularity as a visual form. By the late 19th century, people had found new ways to use the medium for scientific pursuits, artistic inspiration, and exploration, as well as commercial enterprises. Requiring specialized knowledge and equipment to produce, yet increasingly affordable, photography proliferated in this period through the photographic studio. People were eager to have their portrait taken, something which was previously available only to those wealthy enough to afford paintings. In many ways, the photographic studio made portraiture accessible and, much like painted portraits before them, allowed people to present themselves as they wished to be seen, rather than exactly how they were. The social desires and aspirations of sitters conveyed through portraits were matched by the entrepreneurial spirit of the photographers themselves, who advertised their services as novel interpretations of the photographic medium or as catering to a specific clientele. Notable photographic studios in Canada during this time include those of William Notman in Montreal, William Topley in Ottawa, and Hannah Maynard in Victoria.

In Montreal, a woman known only as Madame Gagné was an active member of the photographic community (she was also married to photographer Édouard Gagné), specializing in photo cabinet cards and portraits of Montreal’s Chinese community, possibly because of her studio’s proximity to Montreal’s emerging Chinatown, situated within the Ville-Marie borough.

Asian immigration to Canada began in the 1850s, with individuals—the majority of whom were men—fleeing social and political upheaval at home, or seeking work in a new land. The 1885 Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration lists the occupations of Chinese labourers in British Columbia: many worked as domestic or farm labourers, as merchants, in the clothing trades (boot makers, washermen, sewing machine operators), as miners, or as fish-hands in British Columbia’s canneries (Royal Commission 1885, 363-66). Perhaps most notably, many Cantonese immigrants found employment in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where they were regarded as an inexpensive source of labour; they were paid a fraction of the wages offered to their European-Canadian counterparts.

The variety of labour undertaken by these immigrants is reflected in photographer Chow Dong (C.D.) Hoy’s image of a group of men in front of his studio-general store in Quesnel, British Columbia. As curator Faith Moosang writes, “Hoy’s photographs are important documents of the nascent industries of ranching, farming, and mining in Quesnel, fields in which the men depicted in this group portrait would have worked” (Moosang 2021). Hoy, himself an immigrant from China, also created images that register the diversity of the community in and around Quesnel. Established as an outfitting post for those setting out for gold in the 19th century, Quesnel became a hub for white European and American settlers, Chinese immigrants, and residents of the Kluskis, Nazko, Ulkatcho, and Quesnel First Nations, many of whom came before Hoy’s lens during the decade in which he operated his studio. Moosang regards this as one of the most remarkable elements of the some 1,500 images taken by Hoy: “When so much of what was happening at that time was about cultural marginalization and even erasure, the idea that these very people showed up at Hoy’s studio to celebrate their own existence is a powerful statement” (Moosang 2021).

Initially, many Asian immigrants settled on the West Coast of Canada and about ten percent of British Columbia’s population was of Asian descent by the early 20th century. However, the newly constructed railway also facilitated movement across the vast expanse of Canada, and Chinese communities—Chinatowns—grew up in many urban centres, including Montreal. These close-knit communities fostered small businesses, including restaurants, import businesses, and laundries, and offered a supportive network to those who often faced racism and discrimination in their new home.

The Canadian government and white settler Canadians’ growing animosity towards Chinese immigrants is most markedly illustrated by the imposition of the “head tax,” first implemented in 1885. This law required new arrivals from China to pay an immigration fee, which was $50 in 1885 and increased to $500 by 1903. The head tax was meant to stem the flow of Chinese immigration, but was also premised on the belief that Chinese immigrants were not settlers. Despite their participation in constructing communities and business, not to mention the railway, government officials were doubtful that Chinese immigrants would remain in the country and contribute to Canada’s long-term growth.

Mme. Gagné’s portrait of Mrs. Wing Sing and her son is thus unusual in two respects. Because immigration to Canada was incredibly expensive for Chinese citizens, the majority of individuals who ventured to cross the Pacific were men who would have had greater opportunity to gain employment upon their arrival. Women, such as Mrs. Wing Sing, made up a disproportionately small portion of immigrants from China. Gagné’s portrait of Wing Sing and her son also speaks to the variety of immigrant experiences. The majority of Chinese immigrants living in Canada in the 19th century were offered low-paying work which would have made it challenging for them to afford the luxury of a family portrait—even a photographic one. Nevertheless, Mme. Gagné seems to have found a steady supply of customers in Montreal’s Chinatown, highlighting the importance some may have placed on documenting their presence in their new home.

To explore these issues further, watch “How does the construction of race influence self-portraiture?” from Britain’s National Portrait Gallery. How does this discussion relate to the Canadian works we have looked at?

Mrs. Wing Sing’s clothing, which features a long jacket (ao) with wide sleeves, and thick-soled shoes, is consistent with that expected of the dutiful wife in late Qing-dynasty China. The sheen of the textiles used to adorn Mrs. Wing Sing and her son are most likely silk rather than cotton or wool. However, the jackets worn by the pair are fairly simple and do not feature brocade patterns or embroidery. These elements signal the status of the Wing Sings; however, their clothing also allows us to speculate about the intended audience for this photograph. While it was not unusual for women in 19th-century colonial societies to participate in and maintain pre-colonial practices of dress, even as men adapted to or adopted items from the colonial culture—as is evident in C.D. Hoy’s photograph—it is also possible that Mrs. Wing Sing and her son donned their Qing-dynasty attire specifically for this photograph, just as many students wear their best outfit for picture day, and that their everyday dress was quite different. Like the postcard images taken by Hoy, it may be that this picture was taken to be sent to relatives in China, to demonstrate the success of the family in Canada as well as how they were keeping with the “old ways” even as they settled into their new surroundings.

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.5

Consider the image of Mrs. Wing Sing and her son, as well as that of the men in front of C.D. Hoy’s store in relation to this image from a Chinese immigration certificate. What kind of portraits are these? If, as Susan Sontag suggests, photography implies an act of appropriation, how do these photographs articulate individual identity, and for what purpose?

Today, portraits are everywhere in Canadian society. They are so common that in many ways they seem ordinary, even mundane. However, the extraordinary popularity of the selfie should remind us that the allure of capturing one’s image remains potent, particularly if that image is aspirational, alluding to the most influential or creative version of ourselves.

Not all of the works considered here are self-portraits; however, in each instance, it is possible to view the sitter—and not simply the artist—as an agent in the work’s creation, whether through the subtle styling of their attire or their willingness to turn camera and brush upon themselves. Some of these works contain mere traces of a sitter’s individual identity; others firmly proclaim the sitter’s existence, often in defiance of stereotypes and policies that sought to erase or minimize their presence—both in visual culture and Canadian society.

Historically, not everyone had the opportunity to sit for a portrait and the names of many who did are lost to us today, but just as Syrus Marcus Ware’s activist series reminds us of those working diligently to transform society, portraits remind us of who we were at a particular moment—perhaps caught between worlds or maybe on our way to making ourselves anew.

LEARNING JOURNAL 5.6

Watch author Tracy Chevalier’s TED Talk, “Finding the Story Inside the Painting,” and then choose one of the portraits featured in the OER or on the Art Canada Institute website and write a micro-fiction (max. 500 words) about the individual depicted in the work. Your story should be creative but should also be rooted in the material and visual properties you observe in the image itself. Try starting this exercise with a session of close looking, making note of the details that interest or intrigue you. This is not a research assignment, but you may draw upon the information you find in the OER or on the ACI website.

OBJECT STORIES

- Efrat El-Hanany on Douglas Coupland, Terry Fox Memorial (2011)

References

Brown, Craig, ed. 2002. The Illustrated History of Canada. Rev. ed. Toronto: Key Porter.

Bruchac, Margaret, and Kayla A. Holmes. 2018. “Investigating a Pipe Tomahawk.” Penn Museum Blog, November 9, 2018. https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/investigating-a-pipe-tomahawk/.

Crazybull, Lauren. 2019. “Seeing Through.” Canadian Art, November 4, 2019. https://canadianart.ca/essays/seeing-through-by-lauren-crazybull/.

Dagenais, Maxime, and Severine Craig. 2016. “Arrowhead Sash.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published May 19, 2016; last edited June 27, 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/arrowhead-sash.

Finnane, Antonia. 2008. Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation. New York: Columbia University Press.

Francis, Daniel. 1992. The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian Culture. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp.

Francis, R. Douglas, Richard Jones, and Donald B. Smith. 2008. Destinies: Canadian History Since Confederation. 6th ed. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Gadacz, René R. 2020. “Wampum.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published February 7, 2006; last updated November 5, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/wampum.

Gaudet, Manon. 2019. “More than Picturesque: Cornelius Krieghoff’s ‘Moccasin Seller.’” Magazine, September 19, 2019. https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/your-collection/at-the-ngc/more-than-picturesque-cornelius-krieghoffs-moccasin-seller.

Gibb, Sandra. 2020. “Trade Silver.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published February 07, 2006; last edited August 27, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-trade-silver.

Grandbois, Michèle, Anna Hudson, and Esther Trépanier. 2009. The Nude in Modern Canadian Art, 1920-1950. Quebec City: Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

King, Gilbert. 2012. “Edward Curtis’ Epic Project to Photograph Native Americans.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 21, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/edward-curtis-epic-project-to-photograph-native-americans-162523282/.

Marcel, Kai. 2020. “Tignon.” The Fashion and Race Database, November 23, 2020. https://fashionandrace.org/database/tignon/.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. 2021. “François Malepart de Beaucourt, Portrait of an Architect, Master of a Masonic Lodge in Cap-François, Saint-Domingue.” https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/works/44162/.

Moosang, Faith. 2021. “Through the Lens of C.D. Hoy: How a Chinese Canadian Photographer Memorialized a Community” (online exhibition). Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/the-essay/through-the-lens-of-cd-hoy/.

Nelson, Charmaine A. 2016. “Canadian Fugitive Slave Advertisements: An Untapped Archive of Resistance.” Borealia: Early Canadian History, February 29, 2016. https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/02/29/canadian-fugitive-slave-advertisements-an-untapped-archive-of-resistance/.

Nelson, Charmaine. 1995. “Coloured Nude: Fetishization, Disguise, Dichotomy.” RACAR: revue d’art canadienne/Canadian Art Review 22, no. (1/2): 97-107.

Nelson, Charmaine A. 2014. “Portrait of a Negro Slave.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Published March 3, 2014; last updated: March 4, 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/portrait-of-a-negro-slave#.

Nelson, Charmaine. 2014. “Quebec’s History of Slavery.” Montreal Gazette, YouTube, February 5, 2014. https://youtu.be/jEwyR-nvm3I.

Nixon, Lindsay. 2017. In conversation with Charmaine A. Nelson. “Fugitive Portraits.” Canadian Art, July 17, 2017. https://canadianart.ca/interviews/fugitive-portraits/.

Parker, Rozsika, and Griselda Pollock. 2013. “Painted Ladies.” In Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, 114-33. New ed. London, I. B. Tauris.

Perry, Lara. 2001. “Looking Like a Woman: Gender and Modernity in the Nineteenth-Century National Portrait Gallery.” In English Art 1860-1914: Modern Artists and Identity, edited by David Peters Corbett and Lara Perry, 116-32. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Phillips, Ruth B. 1998. Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700-1900. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Pointon, Marcia. 2013. Portrayal and the Search for Identity. London: Reaktion.

R.B.F. 1938. “Canadian Group of Painters’ Exhibition at Gallery.” Ottawa Journal, February 15, 1938.

Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration: Report and Evidence. 1885. Ottawa: [Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration]. Accessed through Canadiana: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.14563/3?r=0&s=1.

Shepherd, Brittany, and Yaniya Lee. 2018. “In the Studio with Syrus Marcus Ware. Canadian Art, June 20, 2018. https://canadianart.ca/videos/in-the-studio-with-syrus-marcus-ware/.

Skelly, Julia. 2015. Prudence Heward: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/prudence-heward/.

Smither, Devon. 2019. “Defying Convention: The Female Nude in Canadian Painting and Photography during the Interwar Period.” The Journal of Historical Sociology. (32):77–93.

Sontag, Susan. 1973. “In Plato’s Cave.” In On Photography, 2-24. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Thomas, Jeff. 2021. “The Bear Portraits.” Jeff Thomas. https://jeff-thomas.ca/2014/04/the-bear-portraits/.

Vigneault, Louise. 2014. Zacharie Vincent: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute.

Ware, Syrus Marcus. 2021. “Activist Portrait Series.” Syrus Marcus Ware. https://www.syrusmarcusware.com/art/activist-portrait-series.

Wilson, Nicole. 2021. “Sartorial Insurgencies: Rebel Women, Head Wraps and the Revolutionary Black Atlantic.” Atlantic Studies (advance online publication).

Wyon, Joseph Shepherd, and Alfred Benjamin Wyon. n.d. “Indian Chiefs Medal, Presented to commemorate Treaty Numbers 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 (Queen Victoria),” Exhibits, University of Toronto Libraries. https://exhibits.library.utoronto.ca/items/show/2409.

An artistic convention that represents an individual.

Art historian Lara Perry's theory of portraiture that recognizes the dual, and sometimes competing, influence of both the sitter and the artist in the construction of a finished portrait.

A law that regulates the consumption of goods such as food, furniture, or clothing.

A method of research that privileges a non-dominate interpretation of a work; often employed to disrupt the historic systems of power evident within a piece.