Pariah (2008)

by Loren Lerner

The Montreal artist Marion Wagschal (1943–) was one of the first teachers of painting and drawing at Concordia University, where she taught for thirty-seven years. As a feminist artist, interested in empowering women artists and valorizing the ways women experience their lives, she introduced a studio arts course on women and painting. Throughout her career, Wagschal has consistently explored the human figure. “The body,” she believes, “is a kind of battlefield where struggles for survival – political, physical, environmental, psychological – are waged. The body is a map of a life lived.”[1] Intimate moments absorb her; portraits not of the monumental but of the everyday. She never idealizes or romanticizes the body; rather, her figures are suggestive of the liabilities and promises of being human.

In her late sixties, Wagschal began to focus on her own experience of aging. Pariah is a self-portrait wherein she stands alone in a dark space, estranged from the other partygoers. A pitiful figure, oversized and formless, Wagschal compares badly to the beautiful woman in the distance surrounded by fox-like gossipers. The woman, possibly the artist’s memory of her younger self, stares knowingly in her direction, as if to say, “Look what you have become in your old age, a social outcast.” Wagschal peers unrelentingly from behind her beak mask, her bug-like eyes widened in response to the woman’s hawkish stare. She is a buffoonish misfit who has donned a pathetic, oversized clown costume as armour.

Pariah (2008) emerges from Wagschal’s mingling of thoughts and sensations. This stream of consciousness is the association of visual and auditory impressions that flow from a person’s mind. Wagschal describes this process: “There are a lot of elements in my art, my own life, my own interpretation, my own circuitry, my own volition. . . . If you are an artist, you are constantly weaving all that together like a big swirl.”[2] Pariah’s mask references paintings and drawings of Tiepolo’s Punchinello, a low-life character who originated in the largely improvisational Commedia dell’Arte street theatre of early seventeenth-century Italy. Wagschal was drawn to Punchinello, whose mask sets him apart as an outsider unwilling to conform to accepted modes of behaviour or thought. Pariah also purposefully echoes Watteau’s paintings of Pierrot, a clown dressed in a lumpish costume whose piercing gaze confronts the viewer with a look of sadness and defiance.

Wagschal works intuitively to distill diverse types of memories: visual impressions of paintings, drawings, photographs, and cartoons; mental images of events previously experienced; and verbal recollections of stories about her family she heard as a child. Pariah took the artist months to complete. She reworked the painting again and again until she found an image with enough emanations to complete the work.[3] Her canvas reveals the process of art making, like the daubs of pink and grey color in the Pariah’s white costume and the thinly drawn black lines that outline the shapes of figures and spaces.

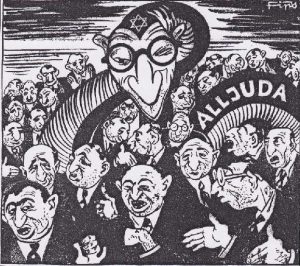

This is a cover cartoon from Julius Streicher’s Der Stürmer, a magazine published from 1923 to 1945. Streicher was one of the earliest followers of Adolf Hitler. Cartoons from Der Stürmer magazine were posted in display cases all over Germany.

Significantly, Pariah is not only connected to Tiepolo and Watteau but also to the concept of the pariah as a Jewish outcast, excluded from humankind. Malicious anti-Semitic cartoons of Jews with long beak-like long noses resembling that in Wagschal’s Pariah appeared in graphic illustrations such as the Brood of Serpents in the German newspaper Der Stürmer. These cartoons played a key role in demonizing the Jew and spreading Nazi propaganda. The Nazis in Germany promoted racial superiority and anti-Semitism to justify the extermination of six million European Jews during World War II. With Pariah, Wagschal expresses a keen awareness of her Jewish identity as the daughter of parents who fled to Trinidad to escape the Holocaust. Wagschal was born there and stayed until she was nine years old; then she and her family immigrated to Montreal. She notes that her mother often spoke about relatives and life in Germany: “They had wonderful lives, they were happy a lot of the time and then everything was completely gone.”[4] Wagschal’s work has multiple associations, including the burden of her mother’s memories of family murdered in the Holocaust.

In the privacy of her home, Wagschal’s mask also assumes some of the adverse characteristics of Pariah. In Big Mouth (2008), Wagschal sits naked on the edge of her bed, the sheets crumpled behind her as if she has recently awakened from a sleepless night. From her mouth she spews small black rocks, symbolic of irritating thoughts and feelings that erupt from her mouth. The angle of her pose discloses signs of age—flabby flesh, broad hips and protruding stomach. Big Mouth, like Pariah, implies that old age is an absence, the result of social invisibility and personal emptiness. Previously youthful and fully visible, the older woman is disregarded by a youth-obsessed society, leading her to become psychologically depressed and alone. In Big Mouth, Wagschal depicts herself sitting like a man, legs apart and hand pressed down on her thigh. Sporting large, boot-like slippers and closely cropped hair, she evokes an ambiguous sexuality that is more masculine than feminine. This is her attempt to construct a defence through male toughness and anger.

Wagschal’s Dog Bath

In Pariah and Big Mouth the mask has decidedly negative associations. All this changes in Dog Bath (2008), with a masking that embodies a positive self-image. In the privacy of her bath, Wagschal is no longer an aging body. Rather, she is an older woman and an artist who inhabits an ever-creating body. Dog Bath is both tender and satirical, contrasting Wagschal’s fond memories of the dogs with which she grew up to the insult of calling undesirable women “old dogs.” As she leans out of the tub to gently stroke her pet, the dog’s eyes express sympathy and everlasting love. In this private exchange between dog and woman—as Wagschal allows her body to respond to the sensations of belonging to the natural order of life—she connects with her animal spirit. In this affirmation, the mask no longer resembles the beak of a bird of prey, but the long furry nose of a friendly pet.

A woman artist’s experience of aging

Wagschal’s Pariah, along with Big Mouth and Dog Bath, show the complexities inherent in creating images related to the aging woman. These include the ways the artist represents her own physical aging, the choices she makes to disguise her identity, and how aging can comprise many identities. A number of themes arise from discussing Wagschal’s works: how women experience old age; the effects of gender and aging on cultural norms and collective identity; and the impact of aging on self-respect and dignity in later life. These themes not only declare the meaning of the passage of time and the value of life, but on a larger scale show how the story of aging is woven together with the story of being an older woman artist.

About the author

Loren Lerner, Professor Emerita, Art History, Concordia University, is interested in women artists, images of children and youth, the interrelations of textual and visual culture, and artistic responses to the Holocaust. Lerner’s recent publications include “François-Marc Gagnon et ses publications” in François-Marc Gagnon et l’art au Québec: Hommage et parcours (2021); “The Ethical Development of Boys in Rousseau’s Emile and Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s Artworks” in Lumen 32 (2021); “The Infant, the Mother, and the Breast in the Paintings of Marguerite Gérard” in Romanticism and the Cultures of Infancy (2020); “Youth and Sunlight: Reflections of Childhood” in Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880-1930 (2019); “The Manipulation of Indigenous Imagery to Represent Canadian Childhood and Nationhood in 19th Century Canada” in Nineteenth Century Childhoods in Interdisciplinary and International Perspectives (2018); and “William Notman’s Home Library: Discovering Underlying Meaning in the Portrait Photograph” in À la recherche du savoir : nouveaux échanges sur les collections du Musée McCord / Collecting Knowledge: New Dialogues on McCord Museum Collections (2016).

Further reading

Arendt, Hannah. The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age. New York: Grove Press, 1978.

Biggs, Simon. “Age, Gender, Narratives, and Masquerades.” Journal of Aging Studies 18, no. 1 (2004): 45-58.

Campbell, James D. “Marion Wagschal: Private Views and Paintings.” C Magazine 107 (2010): 52-53.

Filmore, Sarah, Ray Cronin, Thérèse St-Gelais, Stéphane Aquin, and Marie-Eve Beaupré. Marion Wagschal. Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2015.

Lerner, Loren, ed. Afterimage: Evocations of the Holocaust in Contemporary Canadian Arts and Literature / Rémanences: Evocations de l’Holocauste dans les arts et littérature canadiens contemporains. Montreal: Centre for Canadian Jewish Studies, Concordia University, 2002.

- Frankie Mathieson, “The Feminist Painter's Bold Oeuvre Comes to Life in a New Exhibition Celebrating Canada's Leading Female Artists,” AnOther, February 4, 2016, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/8281/a-closer-look-at-the-confessional-works-of-marion-wagschal. Wagschal explained in a telephone conversation with Lerner on December 13, 2021, that the idea of the female body as a battlefield connects with feminist artist Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Your body is a battleground), a 1989 word and image photographic silkscreen print on vinyl, 284.48 x 284.48 cm. ↵

- Jake Moore and Loren Lerner, Interview with Marion Wagschal at her Private Views exhibition, FOFA Gallery, Concordia University, February 1, 2010. ↵

- Moore and Lerner, Interview with Wagschal, 2010. ↵

- Moore and Lerner, Interview with Wagschal, 2010. ↵

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the systematic state-sponsored murder of six million European Jews during World War II by the Nazis in Germany and their collaborators across German-occupied Europe. In the decade after the Second World War, more than 35,000 Holocaust survivors and their families settled in Canada, mainly in Montreal and Toronto.