INSTITUTIONS

For more than three months in 2008-09, the imposing neoclassical façade of the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG) was transformed by Dzawada’enuxw artist Marianne Nicolson’s The House of the Ghosts. This site-specific project reimagined the cultural institution through projection. The dramatic lighting foregrounded Kwakwaka’wakw imagery in Vancouver’s urban core—a stark contrast to the neoclassical structure imbued with colonial authority. Built in 1906, the building was designed by settler architect Sir Francis Mawson Rattenbury (who also designed the Victoria Legislative Assembly and Empress Hotel in Victoria on Vancouver Island). Initially the site of a provincial courthouse in the 1980s, the building was renovated by architect Arthur Erickson to house the VAG, which relocated there in 1983. This change was part of a larger urban development project in Robson Square in the period. Therefore, the VAG occupies a building that references layers of history and institutions connected to colonial government, authority and power. The building’s links to such authority endure today; it is currently owned by the provincial government and subleased through the City of Vancouver.

Bearing a resemblance to the Canadian flag, Nicolson’s projection stretched across the façade of the VAG, illuminating an area more than ten metres wide. The light transformed the colonial institution of the courthouse—representing the rule of law and colonial power—into a distinctly Indigenous space, specifically a traditional Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial Big House. The alignment of the projection transforms the building’s pillars so that it appears as the post-and-lintel architecture of a Big House. The design of the projected façade features stylized orcas, wolves, owls, and a ghost puppet (a reference to the artist’s paintings), rendered in white, red, and black. Nicolson employs the contemporary media of digital projection, but maintains the formal aesthetic language of the Northwest coast’s Indigenous people.

This artistic intervention directly onto the museum temporarily transformed the structure, challenging its meaning. The artist’s work “symbolizes the survival of Pacific Northwest Coast First Nations cultures and communities, despite active efforts to suppress and eradicate them” (e-flux 2022). Nicolson’s The House of Ghosts is a challenge to the structure and purpose of the museum, bringing to mind the complex histories of power and cultural institutions. The projection draws attention to the ways in which objects in the museum are categorized as art, despite their use/positioning otherwise before arriving at the institution. Nicolson’s work also points to the wealth that is housed in museums, which are significant storehouses for cultural objects, often at great remove from their communities of origin.

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.1

Have you been to a museum recently? Did you ever wonder how the objects got there? Have you ever recognized something from your own culture in a museum? Were you surprised by how your culture was presented? Can you think of a time when you were surprised by how a culture different from your own was represented in a museum?

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- describe how institutions enact authority as arbiters of cultural significance, custodians of prized objects, and narrators of histories, communities, and identities

- analyze the historic trajectory of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, including the development of its physical site, collections, and organization

- discuss artists working within institutions to critique and make prominent their naturalized ways of displaying and conceiving of objects

- explain various types of art institutions (including national galleries, encyclopedic museums, micromuseums, and artist-run centres).

It will take you:

The House of the Ghosts Text 10 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

Institutional authority Video 9 min, Text 28 min

A museum in the city: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Video 5 min, 52 min

Museum interventions Podcast 19 min, Video 4 min, Video 7 min, 12 min, 8 min

Institutional case studies Video 20 min, Video 2 min

Learning journals 7 x 20 min

Total: approximately 5.25 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 8.1 Marianne Nicolson, The House of the Ghosts (2008-9)

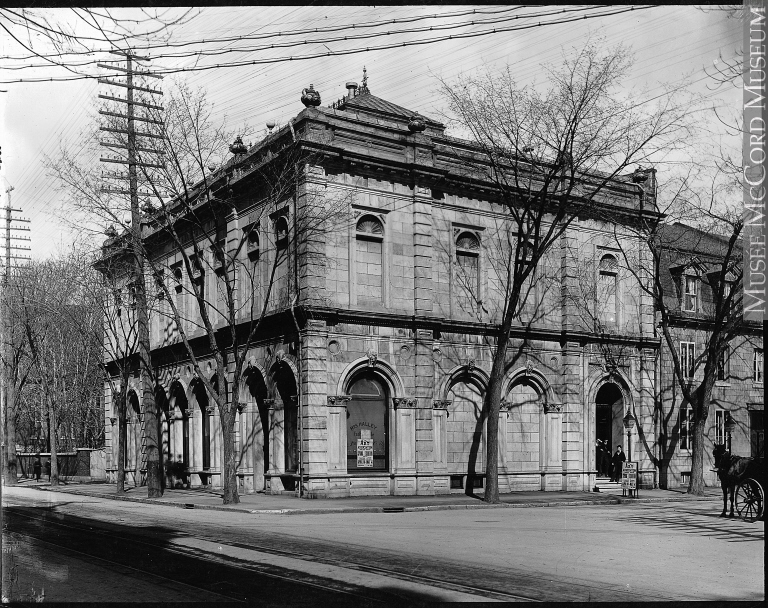

- Fig. 8.2 William Notman & Son, Art Association building, Phillips’ Square, Montreal, QC, (c. 1890)

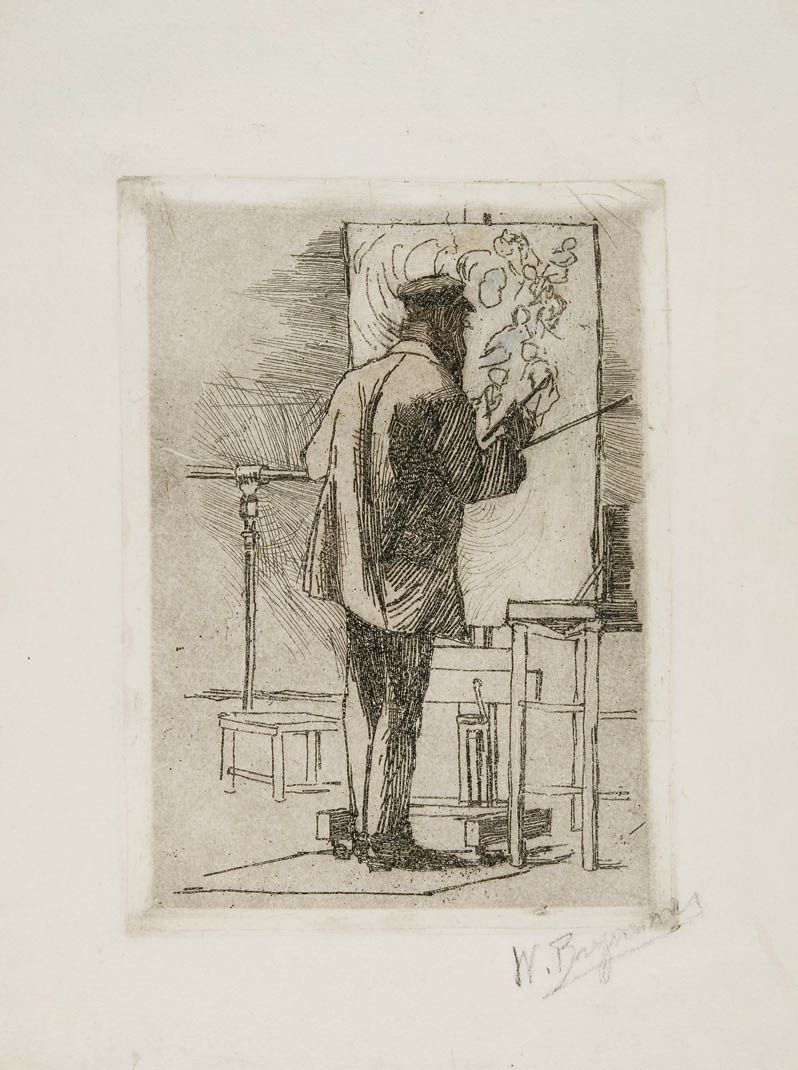

- Fig. 8.3 William Brymner, Old Man Painting in the Louvre, Paris, (1880/81 and 1902/3)

- Moshe Safdie, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

- Luc Bourdon, A Museum in the City (2011)

- Kent Monkman, Another Feather in Her Bonnet (2017)

- Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989)

- Fig. 8.4 James Luna, Artifact Piece (1987)

- Fig. 8.5 Rebecca Belmore, Mister Luna (2001) Agnes Etherington Art Centre

- Fig. 8.6 Spring Hurlbut, The Final Sleep, swans, study skins (2001)

- Fig. 8.7 D’Arcy Wilson, Nest from “The Memorialist, Museology Series” (2016)

- Brendan Fernandes, Authority Inside (2016)

- Moshe Safdie, National Gallery of Canada (1988)

- The World Famous Gopher Hole Museum in Torrington

- Fig. 8.8 Articule

- Fig. 8.9 General Idea, Art Metropole, 241 Yonge Street, Toronto (1974)

Institutional authority

“Museums can make it hard to see.” –Svetlana Alpers, “The Museum as a Way of Seeing” (1991)

Museums have long been considered powerful agents: arbiters of cultural significance, custodians of prized objects, and narrators of histories, communities, and identities. They advance hegemonic values through the stories and objects they display, and also implicitly relegate others to the sidelines by marginalizing or excluding certain narratives and items. Their role is significant, given their public orientation. They sit at the intersection between the state and civil society and function as educational institutions, facilitating research as well as public learning.

Museums themselves have a history to tell; they are more than containers of things. They are complex reflections of the cultures that produce them, and include and reinforce these cultures’ politics, social structures, and systems of thought. Our understanding of museums really starts in the 17th or 18th century, but earlier collections of objects and sites of display influenced the museum’s formation.

The advent of critical museology or museum studies (the examination of the history of museums, their role in society, and operational aspects like curating, preservation, public programming, and education) in the late 20th century was tied to shifts in other academic disciplines like anthropology, sociology, art history, and cultural studies, to name a few. From the 1980s and 1990s onward, scholars began to challenge the supposed neutrality of the museum, producing a large body of scholarship on institutional critique that addresses how museums advance taste and class distinctions (Bourdieu 1984), serve as sites for social performance (Bennett 1995) and the construction of social values (Luke 2002), promote nationalism (Anderson 2006; Duncan and Wallach 1980; Wallis 1994), advance western understandings of culture and ownership (Clifford 1988), and reinforce colonialism by structuring encounters with non‐western cultures (Clifford 1997, Phillips 2011).

Scholars Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach (1980) have identified what they see as some of the underlying ideological objectives of universal survey museums, such as the Louvre. They suggest that the institutional mandate of such museums is tied to the projection of national identity and state power. Benedict Anderson (2006, 163) similarly identifies the significance of “institutions of power,” pointing to the museum as a key site for the production of nationalism. Anderson describes how institutions work to subsume everything to the nation and to render it visible to members of the community (184). The nation feeds on national narratives generated through cultural products. Duncan and Wallach explain how cultural goods fill this void through their symbolism. “Because the state is abstract and anonymous,” they argue, “it is especially in need of potent and tangible symbols of its powers and attributes” (Duncan and Wallach 1980, 457). Thus, the museum, through its architecture and its carefully curated arrangements of art, artifacts, and information, presents narratives that render visible the nation’s values. As Brian Wallis (1994) notes, these curatorial narratives often conceal omissions and mistruths.

Watch the Art Assignment video, “The Case for Museums,” here:

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.2

In Civilizing Rituals, Carol Duncan passionately argues for the critical role museums play:

To control a museum means precisely to control the representation of a community and its highest values and truths. It is also the power to define the relative standing of individuals within that community. Those who are best prepared to perform its ritual—those who are most able to respond to its various cues—are also those whose identities (social, sexual, racial, etc.) the museum ritual most fully confirms. It is precisely for this reason that museums and museum practices can become objects of fierce struggle and impassioned debate. What we see and do not see in art museums—and on what terms and by whose authority we do or do not see it—is closely linked to larger questions about who constitutes the community and who defines its identity (Duncan, 8-9).

Similarly, in “The Art Museum as Ritual,” (1995) Duncan writes, “museums offer well-developed ritual scenarios, most often in the form of art historical narratives that unfold through a sequence of spaces. Even when visitors enter museums to see only selected works, the museum’s larger narrative structure stands as a frame and gives meaning to individual works” (12). She indicates that museums can become the focus “of fierce struggle and impassioned debate” (8) because they often reinforce the values of particular identities and communities.

A museum in the city: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) is one of the most visited and largest art museums in Canada. Located in Canada’s leading cultural capital, Montreal—a city imbricated in the cosmopolitan networks of high culture—the MMFA is a key institution in the “golden triangle” cultural region encompassing Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto.

The MMFA was founded in 1860 as the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) by a small group of collectors and educators with the intent of giving fine arts a greater presence in the emerging city. Although it struggled initially to find community support and a permanent building, a bequest by wealthy merchant and collector Benaiah Gibb in 1877 financed the purchase of land and the construction of the building in downtown Phillips Square. In 1886, landscape painter and associate of the Royal Canadian Academy, William Brymner, was appointed director of the AAM’s school of art.

Read more about William Brymner’s influence on Canadian art while teaching at the AAM in Jocelyn Anderson’s Art Canada Institute biography of Brymner which outlines his “Legacy as a Teacher.” She notes, “Brymner’s approach to teaching was striking: it was defined by his strong commitment to the French academic tradition, but he also encouraged students to develop their own styles. A consideration of Brymner’s career is incomplete without a discussion of his achievements as an instructor at the Art Association of Montreal” (Anderson 2020).

Art historian Anne Whitelaw outlines the MMFAs development in the 20th century:

The AAM became the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 1949 and, in recognition of the importance of francophone culture in the city the moniker Musée des beaux-arts de Montreal was added in 1969. Despite some difficult times the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) was long the centre for artistic activity in English-speaking Montreal. Art classes were formalized in the 1880s under the directorship of William Brymner (1855-1925) and were significantly expanded under Edwin Holgate (1892-1977) and Lilias Torrance Newton (1896-1980) in the 1930s and 1940s and then under Arthur Lismer (1885-1969), beginning in 1947. For much of its history the Museum also held regular exhibitions of works on loan from local collectors, presented an annual Spring Exhibition of works by Canadian artists, and alternated with the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) and the National Gallery in hosting the Royal Canadian Academy annual exhibitions. In addition, private donations and carefully cultivated relationships with major collectors enable the MMFA to build a considerable permanent collection ranging in scope from objects from ancient Greece, to European paintings and sculpture, Canadian and Quebecois art, and the decorative arts (2010, 5).

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.3

Watch the creative documentary A Museum in the City (52 minutes) by Luc Bourdon (2011) and consider the MMFA in relation to Carol Duncan’s arguments about the museum as ritual. What are the rituals of the museum? Who participates in these rituals? Who does not? How does the ritual of the museum entrench certain narratives? And what are these narratives?

The museum continues to expand and in 2019 it opened the Stéphan Crétier and Stéphany Maillery Wing for the Arts of One World, a space that “promotes inclusive values that reflect Montreal, a metropolis made up of close to 120 cultural communities,” that “invites people of different cultures to come together to better understand one another at a time, in this 21st century, when togetherness has become an issue of vital importance” (MMFA 2022). Of late, the MMFA has made a name for itself with exhibitions of work by fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier (2017) and Thierry Mugler (2019).

Kent Monkman, an interdisciplinary Cree artist, created a performance that was showcased as part of the Gaultier show in 2017. This work, entitled Another Feather in Her Bonnet, featured Monkman’s performance alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. Watch the performance here:

According to the MMFA:

For the faux ceremony, Miss Chief wears a white feather headdress created by Gaultier for the wedding gown of the 2002-2003 fall-winter haute couture collection The Hussars. Inspired by headdresses of Indigenous peoples of the Plains, this headdress was originally displayed in the exhibition Love Is Love: Wedding Bliss for All à la Jean Paul Gaultier. In the context of the debate over cultural appropriation, the presence of this headdress in the exhibition demanded a response, so the MMFA invited Monkman to create an artistic commentary. His reply: Miss Chief would gracefully accept Jean Paul Gaultier’s hand in marriage. With his long-time collaborator Gisèle Gordon, Monkman designed this performance to be a symbolic union that represents two artists coming together to challenge ideas of cultural appropriation and build an artistic union based on mutual affection and greater cultural understanding.

“Through the alliance of marriage, we learn to understand and forgive the mistakes of our partners and to build true understanding. Marriage encourages and nurtures new life, new experiences. Today, Miss Chief accepts Jean Paul Gaultier’s proposal of artistic union as an aesthetic alliance leading to mutual respect and cultural understanding,” said Kent Monkman.

Indigenous headdresses are imbued with spiritual significance. An earned honour, they come with protocols and responsibilities. Monkman’s artistic claiming of this faux headdress speaks to the broader stereotype of the Indigenous woman as perceived by the colonial gaze. Through Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman evokes the gender-fluid and/or two-spirit people venerated and accepted by most pre-contact Indigenous nations, whose cross-dressing ways scandalized and were suppressed by European colonists.

As an accompaniment to the performance, Monkman collaborated with Toronto photographer Chris Chapman to create wedding-portrait style photographic art pieces of Miss Chief and Jean Paul Gaultier, adopting the style and presentation of the 19th century French cabinet card format (MMFA 2019).

The figure of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is employed in a number of ways through Monkman’s art practice, not limited to performance work. Chief curator and director of programming at the Art Gallery of Hamilton Shirley Madill explains:

Miss Chief ’s name is a play on the words “mischief ” and “egotistical,” and in its early use also incorporated “Cher” as a way to perform a reimagining of the 1970s pop diva (Katz 2012, 19). Today, she is known as Monkman’s alter ego, living and taking part in art history. In the tradition of Indigenous storytelling, she embodies the mythological trickster and takes the form of a two-spirit, third gender, supernatural character who exhibits a great degree of intellect and knowledge when she is present in a work of art. Monkman uses her to help guide viewers to see new truths. Glamorous, flamboyant, confident, and always high-heeled, she inhabits paintings and appears in installations, performances, and videos. Since her first manifestation nearly twenty years ago, she’s played a central role in correcting accounts of Indigenous histories. Indeed, Miss Chief is the key to much of the artist’s work (Madill 2022).

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.4

Explore some of the artworks depicted in Shirley Madill’s essay on Miss Chief to see the different ways that Kent Monkman utilizes his alter ego in his artistic practice. For example, look at Being Legendary (2018), Portrait of the Artist as Hunter (2002), The Triumph of Mischief (2007), and Woe to Those Who Remember from Whence They Came (2008).

Select a work by Monkman and think about how it functions. In 5 to 10 sentences, describe and explain the medium, what is represented, how Miss Chief is used by the artist, and what message the work conveys to viewers.

Monkman’s work at the MMFA—and in other cultural institutions—is just one of many ways that artists have engaged in institutional critique. Other artists, such as Andrea Fraser, also employ performance personas to unsettle institutions and point to how they structure our ways of seeing and valuing culture. For instance, consider Fraser’s work Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk from 1989, which takes the form of a gallery tour by Fraser’s persona of gallery docent Jane Castleton. As Fraser explains: “Jane Castleton is neither a character nor an individual. She is an object, a site determined by a function. As a docent, she is the museum’s representative, and her function is, quite simply, to tell visitors what the museum wants—that is, to tell them” (Martin 2014).

More broadly, institutional critique can be advanced by artists working beyond performance. Institutional critique is a broad form of art production that art historian Benjamin Buchloh dates to 1960s conceptual art. Buchloh notes the necessity of artist’s institutional critique, given that institutions validate cultural production and that “[t]hese institutions, which determine the conditions of cultural consumption, are the very ones in which artistic production is transformed into a tool of ideological control and cultural legitimation” (Smith 2021, 143).

Museum interventions

In addition to the scholarship in critical museum studies, artists have also drawn attention to the ways in which museums advance agendas through specific institutional practices. The exhibition as a display mechanism has been a key site for critique. In the 1992 exhibition, Mining the Museum, Fred Wilson reworked the displays at the Maryland Historical Society (MHS) in Baltimore to reintroduce previously marginalized narratives about Black and Indigenous histories, revealing the elitism of the museum’s standard exhibition narratives. As Kerr Houston writes, “Working with objects in the collection of the MHS, Wilson unsettled the museum’s comfortably white, upper-class narrative by juxtaposing silver repoussé vessels and elegant 19th-century armchairs with slave shackles and a whipping post. Texts, spotlights, recorded texts, and objects traditionally consigned to storage drew attention to the local histories of blacks and Native Americans, effectively unmaking the familiar museological narrative as a narrow ideological project” (Kerr 2017). Prior to Wilson’s exhibition, in 1987 performance artist James Luna unsettled normative ways of seeing in the museum through Artifact Piece. In this work, Luna placed his body inside a vitrine in the San Diego Museum of Man to prompt visitors to rethink how Indigenous peoples and cultures had been positioned in a critique of display culture.

Art historian Richard William Hill has reflected on Artifact Piece as a breakthrough: “It was one of those works that manages to concentrate many important, emergent ideas into a single gesture at just the right moment – in this case the moment when many Indigenous people were struggling urgently to theorize and express their concerns about their representations in museums” (2018).

Luna’s work went on to influence other artists. In 2001, Rebecca Belmore paid tribute to him with Mister Luna, a playful installation. Now in the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Belmore’s homage of “shiny yellow shoes bask in a halo of vanity lights: the moon-like configuration of lights conspires with the radiance and colour of the piece to generate a visual pun on the subject artist’s name. Mister Luna mingles comic staging and respect in its suggestion that, as an astute and influential articulator of the cultural perspective of aboriginal peoples, James Luna offers illumination and inspiration to all” (Agnes Etherington 2022).

VIEW REBECCA BELMORE’S MISTER LUNA HERE

Figure 8.5 Rebecca Belmore, Mister Luna, 2001. Painted leather shoes, vanity lights, feathers, electrical cords and hardware, 228.6 x 152.4 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

According to Linda Steer, museums today are engaging more and more with artists, which perhaps helps to widen the scope of their vision. This is just one way that we might rethink the histories of collections and collecting from other points of view. Listen to Steer discuss this in her podcast Unboxing the Canon in Episode 7, “Musing on Museums” (19 minutes).

One of the artists featured in Steer’s “Musing on Museums” episode is Spring Hurlbut, winner of the 2018 Governor General Arts Award. The same year that Belmore paid homage to James Luna, Hurlbut created the exhibition The Final Sleep by reconfiguring and displaying 400 objects from the Royal Ontario Museum’s (ROM) collection. Steer notes, “Everything in the exhibition was white, and objects were classified and arranged according to the artist’s logic, not scientific logic or museum logic. She took many skeletons and taxidermied animals from the natural history branch of the museum and arranged them in rows. They were not installed in dioramas, which is the usual way we encounter animal bodies in museums. And the objects weren’t arranged according to a presupposed hierarchy. They were arranged according to the artist’s aesthetic vision.”

When asked if the curatorial intervention was “intended to be an institutional critique, a rumination on life and death, or both,” the artist explained, “The rumination on life and death is completely accurate. While the ROM acknowledges their specimens’ scientific usefulness, their humble deaths go unrecognized. The ROM was grateful that The Final Sleep bridged that gap, and the public was enthralled by the rarely seen study collection. It is a dream of mine to make a permanent installation in a natural history museum” (Clarke 2010).

Watch this excerpt from the film Spring & Arnaud which follows Hurlbut as she recounts the creation of her 2001 installation The Final Sleep at the Royal Ontario Museum (4 minutes).

Established by the ROM Act in 1912, and opened in 1914, The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto is one of the largest museums in North America. In contrast to the MMFA’s focus on art, the ROM is an encyclopedic museum with a collection of more than six million items of global material culture and natural history. The five original galleries were divided among the fields of archaeology, geology, mineralogy, paleontology, and zoology, but have been reorganized into two main galleries of natural history and world culture, which in turn are divided into individual galleries named after significant donors. In 2007, the ROM opened the controversial Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, a Deconstructivist crystalline-form expansion designed by Daniel Libeskind.

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.5

For more on the ROM, watch this video on the history of the institution (7 minutes). Consider how it is similar to the MMFA. How is it different? What are the controversies the video raises? Answer some of the questions posed. Should objects acquired in non-consensual ways be given back to the communities they were taken from?

D’Arcy Wilson is another contemporary artist who, like Hurlbut, engages with the genealogy of natural history collections and the specimens they contain. Nominated for a Sobey Award in 2019, Wilson’s interdisciplinary art-making practice interrogates past and ongoing colonial interactions with the natural world. Her series The Memorialist: Museology (2015-17) included a work titled Nest, which featured a stuffed flamingo that had been “displaced” from a different collection in storage. In 1977 the tropical bird blew off course and was shot down by a Newfoundland fisherman; its body was donated to The Rooms in Newfoundland. Displayed for the first time at the entrance of the exhibition In Some Far Place, the found object was accompanied by a performance during the opening reception, in which Wilson and visitors composed a lullaby for the bird and sang it as “they attempted to lull the flamingo to sleep with awkward song” (Wilson 2022).

VIEW D’ARCY WILSON’S NEST HERE

Figure 8.7 D’Arcy Wilson, Nest, 2011. Collage: gouache, coloured paper and pencil, gold leaf, etching, and c-print on paper. The Rooms.

In contrast to the MMFA or the ROM, The Rooms is a relatively new cultural institution. Opened in 2005, the multipurpose facility houses the Art Gallery, the Provincial Archives, and the Provincial Museum of Newfoundland and Labrador. Both the building’s name and its stunning architecture overlooking the port of St. John’s, reference the gable-roofed sheds, or fishing rooms, common in east coast villages.

Inspired by the 70th anniversary of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Confederation with Canada, in 2018 and 2019 The Room’s two-part exhibition Future Possible gathered artworks and artifacts from its collections and displayed them alongside newly commissioned works. Mireille Eagan, Curator of Contemporary Art, explained that the shows “were commentary in cultural objects—statements, questions and reflections about who we are, expressed through art” (2021, 14).

She continues:

Both Future Possible exhibitions explored the province’s cultural history through archival material, artworks and artifacts. Each object on display was thus an opportunity for viewers to discern stories that existed within the provincial psyche. The exhibitions asked whether revered notions of place — markers that some say identify us as Newfoundlanders and Labradorians — could, or should, be reconsidered. The gallery space also became an exercise in citation: it assembled well-known examples of the province’s culture so that viewers could search for a decipherable taxonomy, a cultural language that informs the province’s identity.

The Future Possible exhibitions were conceived as a way to provide a space to build a history collaboratively through discourse and disagreement. The shows became places and opportunities for artists and viewers to take responsibility for their understanding of this province’s history by actively engaging with its narratives. Throughout the gallery, quotes about the culture of Newfoundland and Labrador were displayed, ready to be dissected for their relevance. Divorced from their original context and sitting alongside some of the artworks they referred to, these words became catalysts for comparison and thought. Viewers could also consider their own biases toward the ideas and works on display.

An entire section in the 2018 Future Possible exhibition for example was dedicated to an encyclopedia entry written in 1949 by the then-editor of Canadian Art magazine, Robert Ayre. He described the art history of “Newfoundland” as being left to “outsiders and amateurs.” His opinion was, and still is, a common bias about pre-Confederation art made here. Juxtaposing his words with artwork and objects created prior to Confederation revealed just how firmly Ayre’s statement was rooted in Eurocentric notions of art — in which trained artists work in traditional fine-art media such as painting and sculpture. The setting also illustrated how that view negated a long and varied history of craft and Indigenous creative production, not to mention the entire art history of Labrador. (2021, 14-16)

Eagan’s observation about writing a history of visual culture in Newfoundland and Labrador echoes the approach of CanadARThistories, as it is:

…an exercise in constantly amending the ideas and narratives that have been created and left for us. After all, the province is constantly changing — enriched with the arrival of waves of New Canadians, and by the greater attention being paid to Indigenous histories, to those who are differently abled, to the histories of women, to craft-based evolutions and to the emergence of a queer-based aesthetic that is a complex reconsideration of labels. Within such developments, institutions such as The Rooms can act as a pivot, a site for discourse. Here we can explore diverse histories, reflect on the institutional shift from objective expertise to offering a place where different perspectives can be brought together, whether they be gestures of care and support or acts of protest. (2021, 21)

Watch Brendan Fernandes’ performance Authority Inside (2016) here.

Authority Inside was part of the 2016 exhibition Lost Bodies, a show curated by Sunny Kerr of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. The show was conceived as an engagement with the Agnes’ Lang Collection of works by West and Central African people, including objects from 19 African countries, representing approximately 80 cultural groups. Fernandes’ Authority Inside is a demonstration of how contemporary artists can critically engage with institutions and their collections. This 2016 choreographed video performance depicts an area off-limits to visitors: the vault of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. The video of this subterranean space opens with the movement of the mobile shelves of the vault, which roll away, apparently of their own volition, to reveal aisles and drawers filled with sculptures. The implication is that the vault is an archive, encyclopedic in scope. Dimly lit, the video conveys an ominous tone, augmenting the viewer’s sense of unease underscored by the slowly-building instrumental music and the jerky movements of the handheld camera. The camera pans the metal shelves of the vault holding the Justin and Elisabeth Lang Collection of African Art, which contains more than 570 sculptures from the 19th and early 20th centuries. As sculptures and masks come in and out of focus, the camera’s movements convey the actions of the off-screen ballet dancer, whose dance on pointe through the vault directs the camera lens. The contrast between the static objects and the animated motion of the dancer is stark. As Fernandes explains, the video alludes to “[the] ambiguous relationship between the body and the archive [and] suggests the equally complex relationship between the African art objects stored in the vault and the African bodies which once danced with them” (2022). Fernandes’ “disembodied animation” of the archive emphasizes the “motionlessness” of the collection. This absence of motion brings to mind the original dances that at one time animated these objects. Moreover, Fernandes points to the history of the Agnes’ collection, specifically drawing attention to the Lang Collection which has not been fully used or displayed as a museum resource due to various factors, including lack of funding.

As the video pans across objects from the collection, viewers might consider how these sculptures came to be located in Kingston. In fact, the Lang Collection entered into the Agnes’ permanent holdings in 1982 as a gift from Justin and Elisabeth Lang of Montreal. At the time of its donation, it was considered the largest Canadian collection of African art in private hands. The Langs were a part of an influential group of patrons whose tastes shaped the definitions and display of historic African art in Canada through the donation of their collections to major art institutions across the country. The Langs acquired sculptures over a period of 40 years, beginning around 1938 and expanding their collection until 1980. The bulk of the collection was acquired through the secondary market, with the Langs making their first trip to the African continent only in 1970. Authority Inside allows viewers to conceive of the Lang Collection in its entirety. Yet the video survey of the vault makes clear the serial nature of the collection, which is distinguished by subtle variations of sculptural forms. The exclusions usually elided in museum displays—which as Francis Haskell notes present themselves as complete narratives and conceal their own construction—are thus made clear to the audience: the collection is not comprehensive. As curator Catherine Hale argues: “[The Lang Collection] . . . reflects the tastes of a particular pair of collectors who developed out of a specific set of social and historical circumstances” (2006, 8). Her research reveals that: “[the collection is very much] a product of the Modernist Primitive ‘taste culture’ that formed during the mid-twentieth century in Canada,” which valued the formal qualities of African visual and material culture (8). “Normalized within the canon of Art History,” this approach emerged out of the European fascination with the so-called Primitive Arts and the anti-modern sentiment of the period (6).

For the exhibition Lost Bodies, Fernandes engaged with two key Canadian collections of historic African visual and material culture: The Justin and Elisabeth Lang Collection of African Art at the Agnes and the collection of the Textile Museum of Canada (TMC). Digital collages are displayed alongside a selection of four textiles from the TMCs permanent collection, and other works are placed in proximity to a selection of objects from the Agnes’ Lang Collection. Several of Fernandes’ pieces also reference African art objects from a third historic African collection: the Seattle Art Museum. Fernandes plays with the conventions of museum exhibition display, adding pencil drawings to the plinths used throughout the exhibition, with markings that reference the patterns of the TMC textiles. Lost Bodies critically considers the histories of these three separate institutions and re-presents their African holdings in a soft intervention. Presenting Fernandes’ contemporary works in response to these collections, alongside a selection of objects from the Canadian collections themselves, Lost Bodies urges visitors to consider the role of collections of African art in North American institutions, and the categories assigned to the objects they hold. Asking visitors to critically assess how they interact with such collections, curator Sunny Kerr frames the exhibition with pointed questions about the display of non-Western art in Western museums: “What does it mean to circle an Igbo elephant mask [in a vitrine] or peer at a Faluni blanket [on the wall] in a Western art museum? … [and] With what fantasies do you receive them?”

The artworks animate and reflect on historic collections to reveal new ways of thinking about the histories of cultural producers, fine art collections and collectors, and Western museum spaces, while posing larger questions about decolonization. As such, Fernandes’ work offers a way of further examining African collections in Canadian museums. This project is necessary, given the lack of information given about these materials and the endurance of a Primitivist ideology that shapes their display in these institutions. For instance, Hale argues: “lack of scholarship and expertise has meant that much information about Canadian collections of African art remains unknown” (2006, 2). This cannot be a task solely assigned to art historians and curators. Contemporary artists, working alongside institutions, can contribute significantly to knowledge production around these collections due to the public accessibility of their artwork. The importance of this endeavour should not be understated, especially given the contentious history of exhibiting African visual and material culture in Canada; the most infamous example being the 1989 exhibition Into the Heart of Africa at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Many contemporary artists, including Fernandes, work in partnership with museums while still critically reflecting on museums’ role in society and the contentious histories of the collections they contain. Through re-presentation, appropriation, performance and choreography, the sculptures, textiles and contemporary artworks in Lost Bodies point to the particular constraints of Western museums: namely, their focus on the formal qualities of the object and the absence of information about the cultural producers who created these works and who used them in their daily lives.

Learn about another artist-museum intervention at the Victoria and Albert Museum in the United Kingdom by watching Opening the Cabinet of Curiosities (8 minutes).

Institutional case studies

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.6

Read “What Is a Museum? A Dispute Erupts Over a New Definition.” Can you write your own definition of a museum? Write a paragraph or two describing what a museum is to you.

Watch this Virtual Walking Tour of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa:

According to Canada’s Museum Act, the purpose of the National Gallery of Canada is “to develop, maintain, and make known, throughout Canada and internationally, a collection of works of art, both historic and contemporary, with special but not exclusive reference to Canada, and to further knowledge, understanding, and enjoyment of art in general among all Canadians” (Government of Canada). Founded in 1880, alongside the RCA, with the support of Canada’s fourth Governor General the Marquis of Lorne, the history of the NGC is similar to the founding of many other art institutions across Canada. Art historian Anne Whitelaw explains:

Despite being founded in 1880, it was officially incorporated only in 1913 by an act of Parliament. Its first director was Eric Brown, an English art critic who was hired by Sir Edmund Walker, a financier and chairman of the National Gallery’s governing board of trustees, to head up the fledgling institution. Despite federal support the National Gallery would be inadequately housed and funded for many of its early years. Originally located in a Department of Public Works building that was also home to the Department of Fisheries, it moved in 1911 to the Victoria Museum building (now the Canadian Museum of Nature), which it shared with the Museum Branch of the Geological Survey of Canada (now the Canadian Museum of Civilization). For many artists, the idea that works of art would be competing for space with dinosaur bones and other natural specimens was inconceivable, and there was much criticism of the status being accorded Canadian art by the federal government. The Victoria Museum would nevertheless remain the home of the National Gallery for many years, until the NGC’s move to yet more temporary quarters in 1960. The Lorne Building, a newly constructed office building that was retrofitted to house the National Gallery, was supposed to accommodate the institution only until funding was found to erect a purpose-built home; but it was not until 1988 that the current building designed by Moshe Safdie (b. 1938) opened in its location on Nepean Point across from the parliament buildings. (2010, 4)

Like the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the NGC was designed by Moshe Safdie. See him describe the process behind his design here:

The NGC is located on the National Capital Commission’s Confederation Boulevard, a 7.5-kilometer ceremonial route linking national sites in Ontario and Quebec. The location is busy, sitting between landmarks and tourist hotspots, including the Peacekeeping Monument, the US Embassy, Major’s Hill Park, and the Royal Canadian Mint, and near Parliament Hill, the Byward Market, and the Alexandra Bridge which spans Ontario and Quebec. The gallery exterior is complemented by a Taiga Garden created by landscape designer Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. Ian Ferguson describes Oberlander’s design:

Oberlander’s inspiration for the Taiga Garden came from the site itself, Safdie’s architecture and the purpose of the new building. She knew that Group of Seven landscapes would feature prominently inside the Gallery and chose as a reference A.Y. Jackson’s Terre Sauvage (1913), an early and influential painting of a rocky landscape with Black Spruce. Working with landscape architect and scholar Friedrich Oehmichen of the Université de Montréal, Oberlander selected species that would encourage up-close observation. (2021)

In her commentary on the NGC, Anne Whitelaw underscores the importance of the NGC to the production of Canadian nationalism and national culture:

Culture has long been the pivotal point around which the contestation of national identity has occurred in Canada. Poised between two major political and cultural powers, politicians and members of the cultural elite have attempted since Confederation to stem perceived encroachments on the nation’s autonomy by controlling the import of cultural goods, and subsidizing local production. As the legislators see it, a strong centralized support of Canadian culture remains the foremost tool in the construction of a Canadian national identity: a tool which has proven useful historically in bringing together the most remote regions of the Canadian political landscape, but which has also served as an important mechanism in ‘acculturating’ immigrant cultures and assigning them a place within the Canadian mosaic. National institutions of culture–the National Film Board, the CBC, the National Museums–function in different ways to ascribe a coherence to, as well as to contain, a diverse set of practices and traditions that may be characterized as ‘Canadian,’ advancing a single unified national culture that would effect a (unified) national identity.

Although the repository of high culture, a realm traditionally associated with universal values that transcend national boundaries, the National Gallery of Canada also figures as an important marker of national culture. This importance goes beyond the gallery’s legislated status as a national institution, with a mandate from the federal government to promote Canadian identity. The gallery’s fostering of national culture is made visible in the exhibition of its permanent collection, and specifically through the display of the work of Canadian artists. It is through this display that a coherent narrative of Canadian art is constructed, a narrative organized around the contributions of Canadian artistic practice to the nation’s growing realization of its status as an autonomous state. Inscribed in the display of Canadian art in the National Gallery’s permanent collection, then, is Canada’s emergent sense of itself as a nation. (2007, 175)

In contrast to large “institutions of power” like the NGC, micromuseums are institutions that are very different from the traditional museum. These institutions tend to be small, independent (meaning they might not receive government funding), informal, and focused on very specific types of objects and artworks.

“No one is more qualified to speak on behalf of artists than artists themselves.” –Jack Chambers (CARFAC 2022)

An important challenge to the power and authority of the National Gallery of Canada took place in the 1960s. London, Ontario artist Jack Chambers challenged the National Gallery of Canada’s stance on artists’ fees and copyright. In 1967, the NGC sent a letter to a number of artists who were participating in a major exhibition of Canadian art at the gallery and asked for permission to reproduce their work. The gallery did not offer to pay the artists for the exhibition or the reproductions, but the gallery was planning to sell the reproductions for their own profit. Chambers wrote to the other artists in the show, organizing them to lobby the gallery of change, and called for them to unite and refuse to work for free. Chambers’ efforts eventually led to the establishment of the Canadian Artists Representation/Le Front des Artistes Canadiens (CARFAC) in 1968, when he and Tony Urquhart, Kim Ondaatje, and other artists collectively demanded the recognition of artists’ copyrights. Their establishment of a national body that enforced minimum fee schedules resulted in Canada becoming the first country to pay exhibition fees to artists in 1975.

Another challenge to larger museums and galleries also began in the 1960s. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, numerous artist-run centres began to emerge in Canada as a parallel structure to the existing museum system. Initiated and managed by artists—hence the name Artist-run Centre (ARC)—many of these organizations were supported by the Canada Council for the Arts. These not-for-profit spaces offered an alternative to the existing government museums and commercial art venues in Canada.

In her object stories essay, curator Amber Berson outlines the history of artist-run centres in Canada:

Canadian artist-run centres were set up as a series of parallel galleries in the early 1970s. They were described as parallel to the established exhibition models of commercial galleries. Artist-run centres, as spaces for exhibiting art and culture, are not unique to Canada—Sweden, for example, has a thriving community of similar spaces, perhaps because it too has a national financial support system for artists. However, artist-run centres occupy a more significant cultural position and are more numerous in Canada than anywhere else in the world. This is primarily because of the longstanding financial support system and policies in place since the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957.

Scholars identify Intermedia Society, founded in Vancouver in 1967 by Jack Shadbolt and Glenn Lewis as the “first multidisciplinary cooperative to receive funding from the Canada Council for the Arts,” though it self-identified as an artists’ association (Bonin 2010, 18). Artist AA Bronson identifies A Space, founded in 1971 in Toronto, as the first true artist-run centre. Artist-run centres in Canada have historically been funded by local, provincial and national arts councils. They generally operate with traditional not-for-profit administrative models, meaning a board of directors and employees. Many centres, though not all, have active membership—made up of artists and community members. These members participate in jury processes and other administrative models. Some artist-run centres operate as exhibition venues, production facilities or provide distribution platforms.

In order to qualify for funding and to formally be considered an artist-run centre, centres must follow the not-for-profit arts organization model, must not charge admission fees, must be non-commercial and de-emphasize the selling of work. This model encourages but does not demand the exhibition of experimental artwork. As some of the first spaces to adopt conceptual art, artist-run centres were among the first spaces to be explicitly devoted to “contemporary” art as something distinct from the established canon of “modern” art. That is, artist-run centres emerged in the 60s and 70s as conceptualism, video, and performance were ushering in the contemporary period and were key to this transition in Canada. Artist-run centres offered artists the ability to experiment, without the responsibility of producing work for sale. They attempted to pay artists for their exhibition and allowed artists to network nationally at a time when conceptual performance art was dominating.

Artist-run centres are often described as laboratories or incubators for artists. Beyond this, they are spaces where risk-taking happens. Beyond artists and art work we see these risks manifesting in the day to day administration of articule and artist-run centres more generally. Today, administrative models in museums, galleries and the general arts milieu recognize the value of engaging in diversity and inclusion practices beyond tokenistic action, in part because artist-run centres showed it was possible and necessary. (2023)

To learn more about an artist-run centre in Montreal called articule read Amber Berson’s essay here.

A.A. Bronson, member of the artist group General Idea describes the milieu in which artist-run centres emerged in Canada in a now-seminal essay on the subject, “The Humiliation of the Bureaucrat: Artist-Run Centres as Museums for Artists”:

Someone sometime must write a really good history of Canadian art in the Sixties and Seventies. This was a unique period of massive development responding to a unique geographical and political situation. Here in Canada something happened that happened nowhere else. The linear construction of the country, the reliance on media, the lack of Canadian identity, the aggressive cultural domination of American popular media, the lack of any real art market at all, the impossibility of competing internationally with New York’s hype system and the machinery of American politics pushing American art down the throats of the entire Western world, the [Marshall] McLuhanistic policy-making of the Canadian government in the mid-to-late Sixties, this constellation of unlikely catalysts crystallized into the post-Capital art scene we experience here in Canada today. One aspect of this system is ANNPAC, the Association of National Non-Profit Artists Centres, a typically limp and bureaucratic title which ignores the erratic and inspired cataclysms which constructed this system, in favour of the elemental description which homogenizes it. (1983)

Bronson was also a key figure in another well-known artist-run centre, Art Metropole in Toronto. Art Metropole was founded by artist group General Idea in 1974, and continues to operate in Toronto to this day. Bronson also noted in his essay on artist-run centres that museums provided inadequate representation of Canadian artists. In the late 1960s and 70s, there were only a small number of isolated commercial galleries in Canada, with scant communication between them, and no art fairs or any other signs of a developed commercial system. Artist-run centres provided a means of artist-led self-determination and were a key source of support for experimental projects such as video works, performance art, and conceptual art, in addition to more conventional art forms.

Intermedia, as Berson notes, is often seen as the first artist-run centre in Canada. Other really notable early artist-run centres in Canada include A Space, founded in 1971 in Toronto; Véhicule, founded in 1972 in Montreal; and Western Front, founded in 1973 in Vancouver. As Shannon Moore notes,

More than 60 years later, artist-run centres continue to exist in large numbers across the country (Artist-Run Centres and Collectives Conference [ARCA] currently represents more than 180). Unique in their programming and mandates, some of these centres have a general focus, while others support specific regions, mediums and groups – such as performance art, print-making, feminist art, disability arts or Indigenous representation. Most of these non-profit spaces do not sell work and instead pay artists and other contributors for their presentations. (2019)

Figure 8.9 General Idea studio/Art Metropole, 241 Yonge Street, Toronto, 1974 Photograph by General Idea

LEARNING JOURNAL 8.7

Have you ever heard the term “parallel gallery”? What about “artist-run centre”? Think about your local art scene: what artist-run centres exist in your region? You can find a directory of all the ARCs in Canada here. Find an ARC in your area and learn more by visiting in person or checking out their website. During your visit identify the following: 1) When was the centre established? 2) Does it have a particular focus or mandate? 3) And most importantly, what artwork is currently on display?

OBJECT STORIES

- Amber Berson on articule (1979—)

- Magdalena Milosz on J.W. Francis (architect), Indians of Canada Pavilion (1967)

- Lianne McTavish on The World Famous Gopher Hole Museum, Torrington, Alberta (1996—)

- Hana Nikčević on Rebecca Belmore, Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) (2017)

References

Agnes Etherington Art Centre. 2022. “Belmore, Rebecca Mister Luna 2001.” https://agnes.queensu.ca/explore/collections/object/mister-luna/.

Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Bartels, Kathleen S. and Crowston, Catherine and Dykhuis, Peter and Fisher, Barbara and Thériault, Michèle and Bonin, Vincent and Wark, Jayne and Wood, William. 2012. Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965-1980. Vancouver, BC: Vancouver Art Gallery.

Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronson, A.A. 1983. “The Humiliation of the Bureaucrat: Artist-Run Centres as Museums by Artists.” In Museums by Artists, edited by A.A. Bronson and Peggy Gale, 29-37. Toronto: Art Metropole.

Buchloh, Benjamin. 1990. “Conceptual Art, 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions.” October (55): 105-43.

CARFAC. 2022. “CARFAC History.” Canadian Artists Representation / Le Fronts des Artistes Canadiens. https://www.carfac.ca/.

Clarke, Bill. 2010. “Spring Hurlbut: Deadfall Dialogues.” Canadian Art, April 15, 2010. https://canadianart.ca/interviews/spring-hurlbut/.

Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth‐Century Ethnography, Literature and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Duncan, Carol. 1995. Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge.

Duncan, Carol, and Allan Wallach. 1980. “The Universal Survey Museum.” Art History 3(4): 448–69.

e-flux. 2022. “Marianne Nicolson: The House of the Ghosts.” e-flux Announcements. https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/38869/marianne-nicolson-the-house-of-the-ghosts/.

Egan, Mireille. 2021. Future Possible: An Art History of Newfoundland and Labrador. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions.

Fernandes, Brendan. 2022. “Authority Inside 2016.” Brendan Fernandes. http://www.brendanfernandes.ca/authority-inside.

Ferguson, Ian. 2021. “Landscape, Art and Architecture: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander at the National Gallery of Canada.” National Gallery of Canada Magazine. September 15, 2021. https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/in-the-spotlight/landscape-art-and-architecture-cornelia-hahn-oberlander-at-the-national

Hale, Catherine. 2006. “African Art at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston, Ontario: The Aesthetic Legacy of Justin and Elisabeth Lang.” MA Thesis, Carleton University.

Haskell, Francis. 2000. The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hill, Richard WIlliam. 2018. “Remembering James Luna (1950–2018).” Canadian Art. March 7, 2018. https://canadianart.ca/features/james-luna-in-memoriam/.

Jessup, Lynda. 1996. “Art for a Nation?” Fuse Magazine (19): 11–14.

Katz, Jonathan. 2012. “Miss Chief is always interested in the latest European fashions.” In Interpellations: Three Essays on Kent Monkman, edited by Michèle Thériault. Montreal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Concordia University.

Kerr, Houston. 2017. “How Mining the Museum Changed the Art World.” Bmore Art. First published May 3, 2017. https://bmoreart.com/2017/05/how-mining-the-museum-changed-the-art-world.html.

Knell, Simon. 2016. National Galleries: The Art of Making Nations. London: Routledge.

Luke, Timothy W. 2002. Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Madill, Shirley. 2022. “Introducing Miss Chief: An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance.” Toronto: Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/the-essay/introducing-miss-chief-by-shirley-madill/.

Martin, Richard. 2014. “Andrea Fraser Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk 1989.” Tate Modern. Published on July 2014. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/fraser-museum-highlights-a-gallery-talk-t13715.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. 2022. “Arts Of One World.” https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/collections/arts-of-one-world/.

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. 2019. “Kent Monkman’s Another feather in Her Bonnet.” Published on February 8, 2019. https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/news/kent-monkmans-another-aeather-in-her-bonnet/.

Moore, Shannon. “The Lacey Prize: Recognizing Artist-Run Centres in Canada.” National Gallery of Canada Magazine. July 19, 2019. https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/in-the-spotlight/the-lacey-prize-recognizing-artist-run-centres-in-canada.

Ord, Douglas. 2003. The National Gallery of Canada: Ideas, Art Architecture. Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Phillips, Ruth B. 2011. Museum Pieces: Towards the Indigenization of Canadian Museums. Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Robertson, Kirsty. 2019. Tear Gas Epiphanies: Protest, Culture, Museums. Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

Robertson, Kirsty. 2011. “Titanium Motherships of the New Economy: Museums, Neoliberalism, and Resistance.” In Imagining Resistance: Visual Culture and Activism in Canada, edited by J. Keri Cronin and Kirsty Robertson, 197–213. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Sholette, Gregory. 2011. Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture. London: Pluto Press.

Smith, Sarah E.K. 2021. “Institutions.” In A Concise Companion to Visual Culture, edited by A. Joan Saab, Aubrey Anable, and Catherine Zuromskis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wallis, Brian. 1994. “Selling Nations: International Exhibitions and Cultural Diplomacy.” In Museum Culture: Histories, Discourses, Spectacles, edited by Daniel J. Sherman and Irit Rogoff, 265–81. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Whitelaw, Anne. 2007. “Whiffs of Balsam, Pine, and Spruce: Art Museums and the Production of a Canadian Aesthetic.” In Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art, edited by John O’Brian and Peter White. Kingston; Montrea: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Whitelaw, Anne. 2010. “Art Institutions in the Twentieth Century: Framing Canadian Visual Culture.” In The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century, edited by Anne Whitelaw, Brian Foss, and Sandra Paikowsky. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, D’Arcy. 2022. “The Memorialist: Museology, Nest.” D’Arcy Wilson. https://www.darcywilson.org/the-memorialist-museology/dpqnc1fysi2fixmcsq3qiskvukjxym.

Ydice, George. 2003. The Expediency of Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Is an archival collection which holds representative samples of broad classifications of objects that communicate an expanse of cultural and natural history.

A large, government sponsored cultural institution and museum that supports the art, culture, and history of its nation as well as its citizens' access to this material.

Small museums with very specific collections or missions. Often independent and/or informal.