BELONGING

From the 1840s to the 1950s, St. John’s Ward was home to many of Toronto’s immigrant communities. Immigrants and refugees arriving in Canada from dispersed regions of the world settled in the city blocks between Yonge, University, Queen, and College Streets, which came to be known as “the Ward.” Black Americans escaping slavery along the Underground Railroad, Irish people fleeing the potato famine, Jews evading persecution in Eastern Europe, and Toronto’s growing Chinese community were among the diverse groups who established roots and lives and built businesses and community services in the densely packed neighbourhood. As journalist John Lorinc writes in his history of the neighbourhood, the Ward “had a distinctive character that set it apart from the surrounding city. . . . [a]s far back as the 1850s, here was a complex and recognizably urban neighbourhood already characterized by ethnocultural diversity, crushing poverty and upward mobility” (Lorinc 2015, 13).

As the official photographer for the City of Toronto from 1911 to 1940, William Arthur Scott Goss produced thousands of photographs of all parts of the city, including St. John’s Ward. Goss was assigned the task of documenting the Ward by Toronto’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Charles Hastings, who wanted to raise awareness about the public health crisis in the area caused by overcrowding and the city’s lack of sanitization standards, safe water, and a proper sewage system. Photographs like Slum Exterior depict everyday life in the neighbourhood. Like most of Goss’s pictures of the Ward, this photo captures squalor, hardship, and suffering in the area, but it also offers a glimpse of the self-determined communities that formed there. Exhibited in venues across Toronto, Goss’s photographs played an important role in making the living conditions in the Ward a priority at City Hall; however, they also fuelled xenophobic ideas about the area and marginalized the racially and ethnically diverse communities that lived in the majority white, politically conservative city.

As art historian Sarah Bassnett writes in Picturing Toronto: Photography and the Making of a Modern City, Goss’s photographs:

Did not merely illustrate the effects of power. Rather, they created the sites where social subjects were produced and power was negotiated. In two photographs intended to show the problems of overcrowding and the ‘need for a municipal lodging house,’ the poor immigrant men who lived in these congested lodging are the object of a surveillance that constitutes them as problematic social subjects, defined by their difference in class and nationality. . .With these instrumental photographs, social problems and social subjects were identified and produced, and the new knowledge they provided made possible new forms of social regulation. (Bassnett 2016, 94)

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.1

In the article “A little girl in Toronto lost to history – and now found,” reporter Chris Bateman tracks down the identity of the once-anonymous subject of one of Goss’s most famous photographs of the Ward by searching for clues in the photograph itself and in the City of Toronto archives.

Read Bateman’s article and then look closely at Slum Exterior. What evidence in the photo might help you learn more about its subjects? What signs of community and belonging do you see?

Goss’s photographs are among the only surviving documents of life in the Ward. By the 1960s, many inhabitants had been pushed out of the neighbourhood, and buildings were expropriated and razed to create space for new developments, including landmarks such as Nathan Phillips Square, City Hall, and the Eaton Centre. In 2015 and early 2016, a small area of the Ward was excavated to prepare for the construction of the New Toronto Courthouse on Armoury Street. Over the course of several months, archaeologists uncovered hundreds of thousands of artifacts among the ruins of row houses, factories, a 19th-century Black church, and a synagogue established by Russian Jews—all vestiges of the communities that made their homes in the Ward.

Watch the video, “Unearthing Toronto’s Multicultural Past” by Infrastructure Ontario, below. During the early stages of the new Toronto Courthouse project, archaeologists discovered thousands of artifacts dating back to when the site was part of St. John’s Ward.

Today, Greater Toronto is celebrated as one of the most diverse cities in the world. St. John’s Ward is a significant part of the history that made it this way. The remnants of the neighbourhood that were unearthed in 2015, even more than Goss’s photographs, are evidence of the ways in which its inhabitants may have fostered community, and a sense of belonging, through religious, social, and cultural centres. Yet the story of the Ward is also a story of marginalization, exclusion, and competing understandings of community and belonging. These themes recur in different ways in the artworks we will look at in this module.

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- describe and analyze different definitions and experiences of belonging in Canada

- explain how settler-colonialism, migration, and multiculturalism have shaped different communities’ relationships to Canada

- discuss debates about the definitions and limits of multiculturalism in Canada

- use visual and textual analysis to show how experiences and definitions of belonging (and unbelonging) can be expressed through images and text.

It should take you:

The Story of St. John’s Ward Text 8 min, Video 3 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

A Place to Belong? Text 15 min, Video 4 min

Inclusions/exclusions Text 30 min, Video 4 min

Multiculturalism debates Text 30 min, Video 77 min

Communities Text 15 min, Video 84 min, Audio 30 min

Learning journals 11 x 20 min = 220 min

Total: approximately 8 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 6.1 Arthur Goss, Slum Exterior (early 1900s)

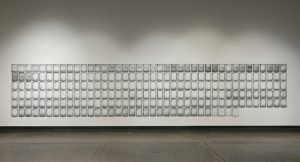

- Fig. 6.2 Deanna Bowen, 1911 Anti Creek-Negro (Muscogee) Petition (2013)

- Fig. 6.3 Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Treaty Card (2004)

- Fig. 6.4 Shelley Niro, 500 Year Itch from This Land is Mime Land (1992)

- Fig. 6.5 Jin-me Yoon, Souvenirs of the Self (1991)

- Fig. 6.6 Ken Lum, There’s No Place Like Home (2000)

- Fig. 6.7 Vera Frenkel, …from the Transit Bar (1992)

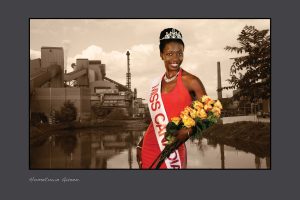

- Fig. 6.8 Camille Turner, Miss Canadiana, Hometown Queen Series (2011)

- Cornelia Wyngaarden and Andrea Fatona, Hogan’s Alley (1994)

- Stan Douglas, Circa 1948 (2014). Interactive digital installation. National Film Board of Canada.

- Fig. 6.9 Stan Douglas, Every Building on 100 West Hastings Street (2001)

- Fig. 6.10 Karen Tam, Tchang Tchou Karaoke Lounge (2008-2010)

A place to belong?

In 1911, around the same time that white social reformers in Toronto began to call upon the city to contain or demolish racially diverse St. John’s Ward, over 4,000 Albertans signed a petition to stop Black Americans from immigrating to the province from the Southern United States. Deanna Bowen’s 1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition (2013) presents photocopies of the 8×11 pages of this petition, including hundreds of pages of signatures, in a grid that occupies nearly an entire gallery wall. Bowen uses strategies from conceptual art to emphasize information contained in this archival document, such as the language of the petition letter, the names of individual signatories, and the sheer number of those named.

For Bowen, this list of names is also a sort of map that can be used to trace the influence of anti-Black racism through Canadian culture and society. She writes,

The petition reveals an expansive network of white Albertans that included Barker Fairley, who at that time taught at the University of Alberta. Fairley’s signature on the petition is a critical part of this puzzle: he was an ardent advocate for the Group of Seven and their unpeopled landscapes. In the Fall 1948 issue of Canadian Art, he wrote that “we now have a body of landscape painting—Group of Seven and post Group of Seven which warms the hearts of thousands of Canadians and gives them the right sort of national pride.” In both instances, seemingly mundane historical documents (or the lack thereof) speak volumes about the values of a community of like-minded people rallying together to stop the influx of Black Muscogee (Creek) peoples, who were, according to the petition, “deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” Following Fairley to the University of Toronto, where he taught from 1915 onward, leads to the inner circles of Massey’s Hart House and the Arts and Letters Club. The violent sentiments in the petition about who constitutes a desirable Canadian strengthen in time to become a mutually regarded white Imperialist vision among Fairley and his friends (Bowen and Wilson-Sanchez 2020).

Barker Fairley’s signature links the group of Albertans who signed the 1911 petition to the art and culture around Massey College at the University of Toronto in a single network. Ties between histories and sectors that we often think of as discrete or disconnected are exposed through Bowen’s work. The wide reach of the anti-Black racism embodied by the petition was reinforced later that same year when the cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier drafted Order-in-Council P.C. 1324. The culmination of a campaign of diplomatic racism, the Order proposed banning all Black immigration to Canada for a period of one year because Black people were seen as unsuitable for the climate. While the Order was repealed and never became law, the statements it made about national identity and race were very clear. The 1911 petition and Order-in-Council P.C. 1324 are examples of white settlers’ organized efforts to define Canadian identity in a way that excluded Black people. The Edmonton petition of 1911 denounced Black immigration as “alarming” and a “serious menace to the future welfare” of the province, and the federal government agreed, hiring agents to discourage immigrants from attempting to cross the United States border (Wittmeier 2020).

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.2

Carefully read the text of the 1911 Anti Creek-Negro (Muscogee) cover letter and petition addressed to Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier. What does this text reveal about the authors’ and signatories’ ideas about belonging in Canada?

To the Right Honorable Sir Wilfred Laurier, G.C.M.G., Premier of Canada,

OTTAWA, Ont. Sir,-

We, the undersigned residents of the city of Edmonton, respectfully urge upon your attention and upon that of the Government of which you are the head, the serious menace to the future welfare of a large portion of Western Canada, by reason of the alarming influx of negro settlers.

This influx commenced about four years ago in a very small way, only four or five families coming in the first season, followed by thirty or forty families the next year. Last year several hundred negroes arrived at Edmonton and settled in surrounding territory. Already this season nearly three hundred have arrived; and the statement is made, both to these arrivals and by press dispatches, that these are but the advance guard of hosts to follow. We submit that the advent of such negroes as are now here was most unfortunate for the country, and that further arrivals in large numbers would be disastrous. We cannot admit as any factor the argument that these people may be good farmers or good citizens. It is a matter of common knowledge that it has been proved in the United States that negroes and whites cannot live in proximity without the occurrence of revolting lawlessness, and the development of bitter race hatred, and that the most serious question facing the United States to-day is the negro problem. We are anxious that such a problem should not be introduced into this fair land at present enjoying a reputation for freedom from such lawlessness as have developed in all sections in the United States where there is any considerable negro element. There is not reason to believe that we have here a higher order of civilization, or that the introduction of a negro problem here would have different results.

We therefore respectfully urge that such steps immediately be taken by the Government of Canada as will prevent any further immigration of negroes into Western Canada.

And your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray.

Dated at Edmonton, Alberta, this 18th day of April, 1911.

NEGRO IMMIGRATION

We view with alarm the continuous and rapid influx of Negro settlers into Northern Alberta and believe that their coming will bring about serious social and political conditions.

This immigration will have the immediate effect of discouraging white settlement in the vicinity of the Negro farms and will depreciate the value of all holdings within such areas.

We fear that the welcome extended to those now coming will induce a very large black population to follow them.

The problems likely to arise with the establishment of these people in our thinly populated province must be plain to all and the experience of the United States should warn us to take action before the situation becomes complicated and before the inevitable racial antipathies shall have sprung up.

We do not wish that the fair fame of Western Canada should be sullied with the shadow of Lynch Law but we have no guarantee that our women will be safer in their scattered homesteads than white women in other countries with a Negro population.

We would therefore urge upon the Government the need for immediate action and the taking of all possible steps to stop Negro immigration into Alberta.

Deanna Bowen’s family immigrated to Alberta from the Southern United States in the early 1900s after the implementation of Jim Crow legislation legalized racial segregation and anti-Black discrimination. Her art often draws on her family history and archival research to explore past and present racism in Canada, connecting her personal relationships and communities to the social and governmental forces that regulate who does and does not officially get to belong in this country.

Below, watch Crystal Mowry discuss Bowen’s touring exhibition, Black Drones in the Hive at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. You may also want to explore some of the other videos here in which Mowry discusses two key works in the exhibition and another video addressing how the Eugenics movement shaped racist ideas and policies both locally and across Canada that demonstrate the ways in which white abolitionists represented Black lives in popular culture.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.3

Without using a dictionary or other sources, define “belonging” and “community.” What do these terms mean to you? How do you experience belonging and community in your life? What roles do country and national identity play in your understanding of these terms? Did learning about the Ward and the 1911 Anti Creek-Negro (Muscogee) Petition challenge, change, or expand your understanding of these terms?

Inclusions/exclusions

Questions of belonging in Canada are inextricable from the history and ongoing realities of settler-colonialism. Beginning with the first treaties between the British Crown and Indigenous nations in the early 1600s, the colonial government has implemented numerous policies and laws that have determined the conditions and criteria for belonging on this land and in this nation, including the 1867 Indian Act. The Indian Act gave the federal government the authority to determine “Indian Status,” or who is and is not considered Indigenous under the law. It also gave them the power to manage reserve lands and to implement a wide-ranging program of eliminating Indigenous cultures and forcing assimilation to settler society, including by criminalizing certain Indigenous cultural practices and expanding the residential school system.

In 1951, the Act to Amend the Indian Act implemented several important changes to the Indian Act by removing some of the most oppressive cultural and religious prohibitions. However, it also tightened restrictions on who is legally considered Indigenous through the introduction of the Indian Register, a centralized list of all “status Indians” in Canada. To qualify as “Indian” under Canadian law, individuals were now required to provide proof of paternal relation to someone who was a band member when a treaty was signed, someone who was a “status Indian” in 1876 when the first Act was passed, or someone who was included on a band membership list. Accepted evidence for proving relations and claiming “status” was limited to legal documents issued by the colonial state, such as birth certificates, marriage licenses, death certificates, and divorce papers. The requirement to prove one’s belonging through paternal lineage made it especially difficult for women to keep and pass on status to their children, particularly if they married a non-status person. Individuals who qualify for “Indian Status” are required to carry a Certificate of Indian Status (now an Indian Status Card), or Treaty Card, to access the resources or benefits to which they are entitled under the amended Indian Act.

Multi-disciplinary Cree/Métis artist Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s 2002 internet artwork, TreatyCard.ca, interrogates the colonial logic and function of the Indian Register. By inviting the audience to participate in a mock-bureaucratic process of applying for “Indian Status” through a website, she raises questions about the criteria for determining who is and is not considered a “status Indian” under Canadian Law, and about the authority of the Register to regulate Indigenous people’s legal relationships both to their communities and to the settler-colonial state.

TreatyCard.ca’s sparsely designed splash page features a reproduction of the handshake Treaty Medal, which was first produced in 1873 and given as a gift to Indigenous Chiefs who signed certain treaties. While the medal was meant to symbolize the agreement and the commitment between the Crown and Indigenous bands, the engraving, which shows a representative of the Crown (likely the Prince of Wales) shaking hands with a reductive stereotype of an Indigenous chief tells a different story. Below the medal, a text written by L’Hirondelle introduces the project:

this site is an attempt to re-dress current relations between natives & non-natives by re-examining the intent, issue and details of the canadian government’s ‘certificate of indian status’ which is more commonly known as ‘treaty card’ in mainly the plains on the landbase now called canada.

when the treaties were signed it was between a chief on behalf of the people and a representative of the queen on behalf of her people. since the treaties were made between at least two parties, then both should have a card. today ‘treaty indians’ are the only holders of the card which is commonly known to be a carry-over from the reserve pass system whereby indian people living on reserves were not allowed to leave (to hunt & gather, visit relatives or carry out business) unless the indian agent who controlled food rations would issue this pass. perhaps this is why the card is a canadian government issue and doesn’t acknowledge the original treaty agreement as much as it still attempts to control the identity & movement of the card holder by branding all “…is an indian within the meaning of the indian art, chapter 27, statutes of canada…” and has efficiently trained card holders to present as a regular part of daily interaction (and sadly even used to boast as some elevated form of government certification). (L’Hirondelle 2002)

By clicking the medal on the website’s homepage, visitors are taken to a form that they can complete to obtain their own imitation “Treaty Card.” L’Hirondelle’s registration system departs from the federal government’s system in several important ways. In addition to requiring documents issued by the colonial state as proof of identity and genealogy, the Indian Register accepts information in only English or French, which means that family names and birthplaces must be translated from Indigenous languages. L’Hirondelle’s form accepts information in Indigenous languages and includes spaces both for “colonized” names and for “alias/original/chosen” names, a detail that is particularly relevant to survivors of residential schools who would have been issued government documents with new westernized names that were assigned to them by the system. L’Hirondelle also expands the eligibility criteria for a card by writing instructions for three groups of users: 1) current holders of Indian Status, who want to revise the way their identity is defined and described in the Indian Register and on their card; 2) Métis and Inuit people who do not qualify for status under the terms of the amended Indian Act; and 3) non-Indigenous people.

The performative and playful openness of TreatyCard.ca can help us think through why and how Indigenous identity has been regulated by the settler government, and how this might impact individual’s and communities’ sense of belonging within Canada and the lands this country occupies.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.4

Visit www.treatycard.ca and complete L’Hirondelle’s mock treaty card registration form. What information would you include to represent yourself? Why? Do you think this is an accurate representation of you? Is there anything about yourself that you think is important but were not able to include on the form?

VIEW SHELLEY NIRO’S 500 YEAR ITCH HERE

Figure 6.4 Shelley Niro, 500 Year Itch from This Land is Mime Land, 1992. Hand-coloured gelatin silver print, sepia toned gelatin sliver print, gelatin silver print, and hand-drilled mat. Art Gallery of Ontario.

The title of Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) artist Shelley Niro’s series, This Land is Mime Land (1992), is a play on the lyrics to U.S. folk-singer Woody Guthrie’s famous protest song “This Land is Your Land,” a rallying cry for wealth and land redistribution, equality, and inclusion in the depression-era United States. The aurally subtle but conceptually significant shift from “this land is my land” to “this land is mime land” is a hint. Mime is a form of acting or theatre that does not use language, but relies on costumes, expression, and gesture to convey meaning. The photos in this series may look playful and innocuous, but they are carefully staged confrontations between settler-colonial stereotypes and self-determined expressions of Indigenous identity.

The series is comprised of twelve photographic triptychs on hand-drilled mats. Each triptych includes photographs titled Historical, Personal, and Contemporary. In the Historical photographs on the left, Niro dresses up as recognizable figures or archetypes from Western culture, including Marilyn Monroe, Santa Claus, Elvis Presley, and a judge. The Personal photographs in the centre of the triptychs are sepia-toned snapshots from Niro’s family’s archive. The third photograph in the group, Contemporary, is a self-portrait of Niro dressed plainly in her everyday clothes. The patterns drilled into the mats surrounding the photos reference the patterns of Kanien’kehá:ka beadwork.

This series was produced in 1992—the same year as the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s invasion of the Americas—in the aftermath of the 1990 Kanesatake Resistance (also known as the Mohawk Resistance or Oka Crisis). Both events, which sparked heated debates about Indigenous-settler relations in Canada, are referenced in Niro’s photographs. In addition to riffing on Woody Guthrie’s alternative U.S. national anthem, the title of this piece references the title of one of the first books on the Kanesatake Resistance, Craig MacLaine and Michael S. Baxendale’s This Land is Our Land: The Mohawk Revolt at Oka (1991). Many of these references appear in the Personal photographs in the middle of the triptychs. In the triptych subtitled Judge Me Not, for instance, Niro’s sister stands in front of Parliament Hill in Ottawa holding a sign that reads, “Our land, our government, our future, our heritage.” In the background, demonstrators carry “Kanesatake Mohawk Nation” and “Peaceful Resolution” posters. The subtitle of another triptych, Mohawk Worker, recalls the name of the Mohawk Warriors, a guerilla group involved in the Kanesatake Resistance.

In the Historical photo of the triptych subtitled 500 Year Itch, Niro gives an intentionally feeble impression of the famous skirt-blowing scene in Marilyn Monroe’s 1955 film, The Seven Year Itch. The subtitle’s play on words, the 500 Year Itch, suggests that the “itch” here is the effect of five centuries of colonial violence and the disenfranchisement of Indigenous people (Harlan 1995, 122). Beside the photo of Niro dressed as Monroe is a Personal photograph of her mother, in nice clothes and styled hair, standing in a fenced yard and smiling happily and peacefully at the camera. When asked about the Personal photos, Niro explains that they are “an indicator of our view of the world” (Art Gallery of Ontario 2021). They prompt the viewer to reassess the photos of Niro dressed in costume or in her everyday clothes on either side.

Watch the following 2017 lecture by Shelley Niro at the Ryerson Image Centre.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.5

Choose three photos or images that represent historical, personal, and contemporary aspects of your identity. Why did you choose these photos? What do you think they might reveal about you, your life, and history to someone who doesn’t know you?

Multiculturalism debates

Since the 1970s, multiculturalism has been an important aspect of Canada’s official national identity and the primary rhetoric used by the federal government to address cultural diversity and belonging in the country. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s Liberal government, Canada was the first country in the world to adopt multiculturalism as an official policy. The multiculturalism policy provided a framework for the government’s response to the growing immigrant populations after World War II, the effects of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec, and struggles for racial equity led by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of colour) communities since the 1960s. When Prime Minister Trudeau introduced the policy to the House of Commons in April 1971, he emphasized its relationship to the Official Languages Act of 1969, stating, “Although there are two official languages [English and French], there is no official culture.” While celebrated in Canada and abroad, Canada’s multiculturalism policy has been marked by internal contradictions from its very beginning. As Trudeau’s statement reveals, it simultaneously sought to embrace differences and to assimilate Indigenous people and new Canadians to one, or both, of the official language communities.

In 1988, Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government passed the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, turning the policy that was initiated in 1971 into a law. The Act was lauded for recognizing that “cultural diversity is a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society.” However, it has also been intensely debated. Indigenous and Canadian Studies scholar Eva Mackey has critiqued the limited definitions of “cultural diversity” and “multiculturalism” within the Act, arguing that they construct “the idea of a core English-Canadian culture, and that other cultures become ‘multicultural’ in relation to that unmarked, yet dominant, Anglo-Canadian core culture” (Mackey 2002, 15). In other words, “multiculturalism” was enshrined in the law as an umbrella term for any person, community, or cultural expression that was not English and not white. According to Mackey, multiculturalism “has as much to do with the construction of identity from those Canadians who do not conceive of themselves as ‘multicultural’ as for those who do” (16). Within the terms defined by the Act, “the power and choice to accept difference, to tolerate it or not, still lies in the hands of the tolerators,” i.e., the white English majority (29).

In their analysis of multiculturalism, art historians J. Keri Cronin and Kirsty Robertson note that “any notion of Canadian identity” is:

Constructed atop a history of disempowerment, disenfranchisement, and cultural genocide––primarily of Aboriginal peoples but also of a litany of others who didn’t fit a given period’s definition of what it meant to be Canadian. . . .Multiculturalism is often used in Canada as a tool of control. It is often described as if settler nationality is a fait accompli, needing only a myth of unity into which newcomers can assimilate with ease. As often as not, events and actions that rub against the grain of this forceful idea are dismissed in a sort of syllogistic logic of belonging: Canada is not racist, and therefore racist actions that occur in Canada are, by definition, anomalous rather than systemic. This has been a powerful politics over the years and one against which numerous artists, writers, politicians, lawyers, and others have strongly reacted. (Cronin and Robertson 2011, 142-145)

VIEW JIN-ME YOON’S SOUVENIRS OF THE SELF HERE

Figure 6.5 Jin-me Yoon, Souvenirs of the Self (Postcard Series), 1991. Simon Fraser University Art Gallery

In the series Souvenirs of the Self (Postcard Series) (1991), Korean-Canadian artist Jin-me Yoon photographed herself at iconic sites in Banff, Alberta, a popular tourist destination in the Rocky Mountains and Canada’s oldest national park. Yoon wears the same clothing––a Nordic-style sweater and jeans––and adopts a similar stance in each photo, one foot slightly in front of the other with her arms at her sides. She looks directly and neutrally at the camera as she poses in front of various scenes including Lake Louise, a vista featuring the Banff Springs Hotel, in downtown Banff, beside a vitrine in the Banff Park Museum; beside a plaque commemorating Chinese railroad workers; and with a group of white tourists and their East Asian driver in front of a chartered bus. At first glance, the photos might resemble conventional, slightly bored, tourist shots. By printing and distributing them as postcards, however, Yoon sets up an interplay between official and personal souvenirs, between the postcards sold at tourist bureaus and the type of photos individuals might take with their cameras or phones.

The ambiguous status of these photographs provokes questions about their subject: Is Yoon an official representative of the quintessentially “Canadian” landscape she occupies? A visitor? What is her relationship to these sites and the national narratives they represent? What assumptions about race, nationality, and belonging do we, as viewers, bring to the images?

Each photo is accompanied by an ironic two-line caption describing the location it depicts, and the thoughts and actions of its female subject. The captions for the photos in which Yoon stands in front of Lake Louise and the Banff Springs Hotel, for example, “celebrate” the colonial history of Canada by inviting the viewer to “Feast your eyes on the picturesque beauty of this lake named to honour Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, daughter of Queen Victoria” and “Indulge in the European grandeur of days gone by.” As Hyun Yi Kang has written, such exultant statements “can be effected only through a willful erasure of both the native populations displaced by the European settlers in the figuration of ‘the Canadian wilderness’ as well as the non-European immigrants and their contributions to the establishment and growth of Canada. The unabashed nostalgia for the ‘days gone by’ is riddled with a certain antipathy for the continued ethnic and cultural diversification of Canada through immigration” (1998, 33).

Banff National Park is located on the traditional territory of the Kootenay, Stoney, Blood, Peigan, Siksika and Tsuu T’ina First Nations peoples. The federal government designated the land a National Park in 1885 in part to attract tourists to the region and to increase passenger traffic on the newly constructed western leg of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which had been built by thousands of temporary Chinese workers in extremely dangerous and deadly conditions. The pristine “Canadian” wilderness that images of Banff have long represented in national narratives is the product of settler-colonialism and immigrant labour. Yoon’s postcards unravel the tourist industry’s picture of Canada, prompting the viewer to ask themselves who belongs in this landscape, and to whom this landscape belongs.

Hyun Yi Kang explains the connection between the histories embedded in Yoon’s postcards and multiculturalism:

On [the back of] each postcard panel, three vertically arranged captions, written in Japanese, Chinese, and Korean proclaiming, “We too are the keepers of this land,” attest to the differential processes of racialization and the incongruous connections of ethnic specificity and racial categorizations. While this tri-lingual declaration can serve as an empowering slogan that seeks to claim a space of entitlement for Asians in both the literal and figurative Canadian national landscape, it also simultaneously indicates an ongoing struggle for political and cultural recognition. In that vein, I read these vertical captions and their adjoining placement on “A 100% Canadian Product” as figuring the coalitional identity of “Asian Canadian” as a product of Canada’s own specific history of anti-Asian racism. . . .On this note, the tri-lingual caption challenges the bi-lingual [English and French] debates, which proffer only two possible choices for the official language of a much proclaimed “multicultural” Canada. The connections among geography, language and community are never organic but forcefully dictated, and as such, they demand careful calibration (34-35).

The viewer is a key element in making meaning of the work which relies on pre-existing stereotypes for the artwork’s legibility. It makes racism visible, and offers an examination of the idea of home and belonging; it asks questions about who gets to be seen as a citizen and how these ideas are always measured against a mainstream or centre that is not racialized (i.e., white) despite government and societal efforts to tout diversity and multiculturalism.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.6

Take a photo of yourself at a site that represents the city, town, or neighbourhood where you currently live. Why did you choose this site? How does it represent the place you live? What is your relationship to this site and place?

VIEW KEN LUM’S THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HOME HERE

Figure 6.6 Ken Lum, There is no place like home, 2000. Six inkjet prints. National Gallery of Canada.

Like Yoon, Vancouver-based artist Ken Lum uses photography and text to pose questions about identity, race, and belonging within the context of Canadian multiculturalism. Originally commissioned for a museum in Vienna, Austria, his billboard-sized work, There is no place like home (2000), took on new meanings when it was displayed on the side of the Canadian Museum of Photography in Canada’s national capital, Ottawa, in 2002. The format and design of There is no place like home borrow from the language of advertising, but strategically defies advertising’s clarity. These formal characteristics and the work’s location in the national capital might have led some viewers to “mistake the billboard for an official Canadian government advertisement extolling the virtues of Canadian multiculturalism through a cautionary tale of racial strife” (Foo 2005, 40).

There is no place like home is a grid of photographs of six people of different races, ages, and genders interspersed with texts in English and French expressing different feelings about their unspecified “homes.” The placement of the texts above and between the photos undermines efforts to definitively attribute each sentiment to a specific individual; however, in the context of Canada’s capital, the pairings also facilitate stereotypical associations among race, nationality, and belonging. For example, the text above an angry-looking white man reads “Go back to where you come from! Why don’t you go home?” The text above a brown woman wearing a head covering states “I’m never made to feel at home here. I don’t feel at home here.” By strategically leaving the work open to interpretation and asking the viewer to conceptually connect each photograph to a text, Lum encourages us to reflect on the assumptions that we are bringing to them. Why would we connect the feelings expressed in one text to a particular person and not another?

Cynthia Foo explains There is no place like home within the context of Canadian multiculturalism:

Rather than a possible ‘united in diversity’ reading of multiculturalism (and therefore an idealized notion of Canadian citizenship), There Is No Place Like Home instead erodes a static sense of ‘home,’ sense of the ‘nation,’ and thus also a clear sense of which individuals are seen as ‘citizens.’ . . .Lum’s There’s No Place Like Home thus answers as it questions: there is no (such) place as ‘home,’ if this home or nation is to be reliant on a homogenous understanding of belonging (this approach which thus redraws the boundaries between insider and outsider). . . . Fraught as it is with anxieties, displacements, and porous borders, a globalized model of Canadian citizenship may thus suggest a model in which seemingly fixed identities are only fixed in relation to others (45).

VIEW IMAGES OF VERA FRENKEL’S . . . FROM THE TRANSIT BAR HERE

Figure 6.7 Vera Frenkel, …from the Transit Bar, 1992. Six channel laser disk installation and functional piano bar. National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Charles Hupé.

Multimedia artist Vera Frenkel’s interactive installation . . . from the Transit Bar (1992) takes a very different approach to questions of home, homeland, and belonging by presenting the personal stories of fifteen of her friends whose families had immigrated to Canada. First exhibited at DOCUMENTA XI in Kassel Germany, . . . from the Transit Bar is an operational bar, where visitors can sit at tables and chitchat over drinks as six videos play on monitors installed throughout the constructed room. The participatory and social dimensions of the work make it an early example of relational aesthetics, an approach to artmaking that turns interactions between audience members into part of the work. For Frenkel, the types of spontaneous encounters that might happen within the fictional but functional space of the Transit Bar are vital to the experience of the piece. Perhaps you will sit with a friend for a while, or strike up a conversation with a stranger at a table. Maybe you’ll find yourself alone in the familiar but strange setting to watch and reflect on monitors displaying fragmented recordings of people in Canada speaking about displacement, escape, and exile.

Although all the people who appear in the videos in this installation spoke English during the recordings, Frenkel overdubbed the videos in Polish and Yiddish, and added subtitles that alternate between German, French, and English. These modifications meant that the predominantly English and French speakers who viewed the work when it was first displayed at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa would be able to grasp only parts of the stories.

Sigrid Schade analyzes Frenkel’s use of language and translation in . . . from the Transit Bar:

National languages and dialects, accents, and slang, delineate the field within which a speaker is situated as belonging or foreign. Not only belonging to a community depends on the mastery of this field, but also participation in its goods: whether professions may be pursued, whether qualifications are recognized or love returned. . . . from the Transit Bar distinguished between national languages that have been politically and economically dominant in Europe since WWII (English, French, German), a national language that was marginalized (Polish), and a language that was almost extinguished or banished into exile along with those who spoke it (Yiddish). Only those who speak Polish and Yiddish can understand all the stories of the voice-over, whereas the dominant languages are fragmented and shifted into the marginality of the subtitles, only rendering part of the stories (2013, 160).

Watch Vera Frenkel discuss …from the Transit Bar with the National Gallery of Canada:

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.7

Vera Frenkel describes …from the Transit Bar as “a place where uncertainty is a form of home.” Reflecting on what you now know about this work, what do you think she means by this description? How does uncertainty relate (or not) to your own understanding of home?

Artist and art historian Bojana Videkanic has written that “creating art in the ‘Canadian’ context means challenging the ideas of multiculturalism, national identity, and social identity” (2006, 32). In different ways, each of the works discussed so far in this module participate in this struggle, and taken together, they show how it unfolds across many different contexts––political, personal, bureaucratic, social, cultural, and geographic, among others. Camille Turner’s satirical alter-ego “Miss Canadiana” is another example. Turner started performing as Miss Canadiana on Canada Day, July 1, 2002. Dressed as a beauty queen in a bright red gown, a sparkling tiara, and a sash displaying her title, “Miss Canadiana,” she staged a guerrilla performance at the annual festivities celebrating the anniversary of Canadian Confederation on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Turner describes Miss Canadiana as a parody on “missing the mark of being Canadian” (Petty 2017, 171). However, the performance reveals as much about audiences as it does the performer.

As Sheila Petty explains,

[Turner] wants people to interact and consider their personal response to her image as “all that is Canadian” –– “a representation of Canadianess.” (Grant 2005, 21) Some credulous people have mistaken her for “Miss Canada,” the queen of a beauty pageant that ended in the 1980s. . . .She only dispels the myth if people ask, “Is this for real?” Turner has mused that she finds it fascinating that one can wear or put on an identity without people challenging or questioning it. In Dakar, Senegal, “a white French woman said to her, ‘When you are Miss Canadiana, I don’t even notice you’re black,” foregrounding whiteness as the always assumed neutral and presupposed category, which serves to reinforce difference rather than engaging with it (Barnard 2005, D4). . . . In essence, Turner is appropriating and restyling Canada, seeking to right the erasure of black Canadian experience. In Regina, members of the Daughters of Africa group felt that Turner was taking their “image of black Canadian identity into the mainstream.” (Barnard 2005, D4) (Petty 2017, 173)

Turner has performed as Miss Canadiana all over the world. In the Hometown Queen series, she brings the character back to Hamilton, Ontario, where her family immigrated to Canada from Jamaica, and where Turner lived from age nine until she was in her early twenties. The photographs in this series were created in Turner’s studio. She photoshops colour portraits of herself dressed as Miss Canadiana onto sepia-toned photos of places in Hamilton that hold significance to her, creating a sense of contrast between the figure and environment. The steel mill depicted in the photo above represents the local manufacturing industry and was where her father worked as a boilermaker.

According to TV Ontario, Hometown Queen is “ultimately is a photo about belonging and a search for a sense of home.” Watch TVO Arts’ short documentary about the origins of Miss Canadiana (2002-present) and the Hometown Queen Series:

Communities

The first two sections of this module explored belonging through the lenses of settler-colonialism, multiculturalism, and migration. In this final section, we will look closely at communities as sites of belonging. The story of St. John’s Ward at the beginning of the module is just one example of how processes of forced and voluntary migration have led to the formation and disappearance of vibrant communities across this country. Remember that the destruction of the multicultural Ward in Toronto was led by a municipal government and groups of citizens who thought it did not belong in the centre of “their” city. In this way, the Ward is a reminder that Canada’s multicultural cities have been sites of struggle over different ideas of belonging.

In Vancouver, a similar struggle to the one in the Ward played out in “Hogan’s Alley,” which was the popular name for the small area between Prior, Union, Main and Jackson Streets within the larger Strathcona neighbourhood. Beginning in the early 1900s, Strathcona became home to many of Vancouver’s immigrant communities, who faced housing discrimination in other parts of the city. Its proximity to the Great Northern Railway station also made it a convenient location for the many Black men who worked as porters on the Canadian Pacific Railway, and formed the first Black railway workers’ union in 1917. Most of Strathcona’s Black residents concentrated in Hogan’s Alley, which grew into a vibrant cultural hub. Restaurants, speakeasies and music clubs, performance spaces, and other social and cultural institutions lined the streets along with residential dwellings. By many accounts, the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel at the corner of Prior and Jackson Avenue was the social heart of the community.

Listen to episode four of Historica Canada’s podcast, A Place to Belong: A History of Multiculturalism in Canada, on the development and destruction of Hogan’s Alley (first aired on June 16, 2021). CONTENT WARNING: This episode contains references to specific instances of anti-Black racism and violence.

Like St. John’s Ward, Hogan’s Alley was variously neglected and targeted by the majority-white city’s changing bylaws and investment in “urban renewal.” In 1967, the City of Vancouver began demolishing the neighbourhood to construct a highway. Although wider community activism ultimately thwarted the construction, it was not until after the first phase was complete and the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts had been built through Hogan’s Alley.

In the early 1990s, filmmaker Cornelia Wyngaarden and curator Andrea Fatona started to research the disappeared neighbourhood, scouring municipal, media, and personal archives, and talking to people who lived there. Their 1994 documentary Hogan’s Alley tells the story of the community through interviews with three women, Thelma Gibson, an African-Caribbean dance teacher, Pearl Brown, a local jazz singer, and Leah Curtis, who shares her experience as a lesbian growing up in Hogan’s Alley in the 1960s. Each woman offers a different perspective on life in Hogan’s Alley, reflecting some of the diversity of the neighbourhood and showing how even close-knit communities may be tenuous sites of belonging. As Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods explain, “All displaced persons from Africa to Africville have different desires for home. They want to build new homes in places that have barred their entry. They also want to reimagine the politics of place” (2007, 5-6).

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.8

Explore the Black Strathcona Project website. Listen to the stories of ten other inhabitants of Hogan’s Alley. Based on what you learned about their experiences, how would you describe this community?

Vancouver-based conceptual artist Stan Douglas’s Circa 1948 (2014) offers yet another examination of Hogan’s Alley. With support from the National Film Board of Canada, Douglas created historically accurate interactive 3D digital models of two long-lost Vancouver sites: Hogan’s Alley and the Old Vancouver Hotel. Accessible through a free iOS app, Circa 1948 allows users to navigate the neighbourhoods’ streets and spaces, and to encounter the ghosts of their inhabitants. From the fragments of stories gathered through these encounters, users can piece together larger narratives about prejudices, threats, power dynamics, and bonds that shaped these communities.

Watch this short video walk through of Stan Douglas’s Circa 1948 app:

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.9

Download Stan Douglas’s Circa 1948 app and explore the streets of Hogan’s Alley. How does it feel to be “in” the neighbourhood? How would you describe your relationship to Hogan’s Alley as a user of Douglas’s app?

Circa 1948 is a very close study of a specific place at a specific moment in history. The spaces and places you see as you wander its digital streets are the result of extensive archival research and careful reconstruction. The stories, however, are fictional. In many of his works, Douglas combines site-specific exploration and storytelling to investigate and uncover erased or repressed histories.

Compare the representational strategies that Stan Douglas uses in Circa 1948 and his earlier work Every Building on 100 West Hastings Street (2001), by reading this excerpt from Gabby Moser’s CanadARThistory essay:

Unlike photojournalistic images of the neighbourhood, which show sidewalks busy with cars and people, Douglas photographs an empty West Hastings Street. While this is usually a bustling street, even late at night, the artist blocked off the sidewalk with city permits to photograph its sidewalks empty of people. If you look closely, temporary “no parking” signs dot the lampposts in the image. Without human subjects in the scene, the photograph recalls documentation of Hollywood film sets and studio constructions of city facades, referencing Vancouver’s history as ‘Hollywood North,’ an affordable stand-in for American cities in movies and television series. But removing the neighbourhood residents from the camera’s gaze is also a response to decades-long questions about the ethics of street photography, particularly when documenting poorer urban areas. The Downtown Eastside was often depicted in news media across Canada at the time Douglas was working, but while photojournalists frequently turned the camera’s lens towards the neighbourhood’s unhoused residents, the artist purposely removes them from view to avoid re-victimizing them a second time, as photographer Martha Rosler once famously argued.

Some of the bodies missing from the block were forcefully disappeared, however, by police enforcement of anti-loitering laws, or more nefariously, drug overdoses and the disappearances and deaths of women involved in sex work. Douglas’s ability to control the movement of bodies across the streetscape has led several commentators to question if a problematic power dynamic is still at play between the photographer and his unpictured subjects. It is telling that, in 2003, the Vancouver Book Award was presented as a tie between Heroines by Lincoln Clarkes—a series of black and white photographs, inspired by 1990s fashion advertising, of unnamed women subjects in the Downtown Eastside—and a small catalogue devoted to Every Building on 100 West Hastings produced by the Contemporary Art Gallery: a tie that speaks to the charged place the Downtown Eastside occupies in citizens’ imaginations.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.10

Compare and contrast Circa 1948 and Every Building on 100 West Hastings Street. What strategies does Douglas use to evoke ideas of community and belonging without explicitly depicting people? Why do you think he does this?

VIEW KAREN TAM’S TCHANG TCHOU KARAOKE LOUNGE HERE

Figure 6.10 Karen Tam, Tchang Tchou Karaoke Lounge, 2008-2010. Interactive installation with neon signs, rope light, wood, fabric, foam, disco ball, plexiglass, paper cutout, microphone, speakers, karaoke videos.

Montréal-based artist Karen Tam’s research focuses on the constructions and imaginations of “ethnic” spaces through installations in which she recreates Chinese restaurants, karaoke lounges, opium dens, curio shops and other sites of cultural encounters. Watch Tam’s 2020 lecture at Emily Carr University of Art and Design below.

LEARNING JOURNAL 6.11

Revisit your answer to Learning Journal 6.3. Has your understanding of the concepts of belonging and community changed after completing this module? How would you define these terms and your relationship to them now? Are there one or two artworks in particular that impacted your thinking? How and why?

OBJECT STORIES

- Christopher Régimbal on Vera Frenkel, …from the Transit Bar (1992)

- Gabrielle Moser on Stan Douglas, Every Building on 100 West Hastings (2001)

- Michelle Gewurtz on Shelley Niro, Homage to Four in Paris (2017)

References

Art Gallery of Ontario. 2021. “(Re)Framing Device.” December 15, 2021. https://ago.ca/agoinsider/reframing-device.

Bassnett, Sarah. 2016. Picturing Toronto: Photography and the Making of a Modern City. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Bowen, Deanna, and Maya Wilson-Sanchez. 2020. “A Centenary of Influence.” Canadian Art, April 20, 2020. https://canadianart.ca/features/a-centenary-of-influence-deanna-bowen/.

Cronin, J. Keri, and Kirsty Robertson, eds. 2011. Imagining Resistance: Visual Culture and Activism in Canada. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Day, Richard. 2000. Multiculturalism and the History of Canadian Diversity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Foo, Cynthia. 2005. “Portrait of a Globalized Canadian: Ken Lum’s There Is No Place Like Home.” RACAR: revue d’art Canadienne/Canadian Art Review 30(1-2): 39-47.

Harlan, Theresa. 1995. “As in Her Vision: Native American Women Photographers.” In New American Feminist Photographies, edited by Diane Neumaier, 114-24. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Kang, Hyun Yi. 1998. “The Autobiographical Stagings of Jin-me Yoon.” In Jin-me Yoon Between Departure and Arrival, edited by Judy Radul, 23-42. Vancouver: Western Front.

Kin Gagnon, Monica. 2000. Other Conundrums: Race, Culture, and Canadian Art. Vancouver: Arsenal Press.

Lorinc, John, Michael McClelland, Ellen Scheinberg, and Tatum Taylor, eds. 2015. The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto’s First Immigrant Neighbourhood. Toronto: Coach House Books.

Schade, Sigrid. 2013. “Migration, Language, and Memory in ‘…from the Transit Bar’ at DOCUMENTA IX.” In Vera Frenkel, edited by Sigrid Schade, 155-71. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Wittmeier, Brent. 2020. “History of Black Immigration Sheds Light on Forgotten Connection between Alberta and Oklahoma.” University of Alberta Folio, February 05, 2020. https://www.ualberta.ca/folio/2020/02/history-of-black-immigration-sheds-light-on-forgotten-connection-between-alberta-and-oklahoma.html

A triptych is an artwork composed of three individual panels placed side-by-side.