The Provincial Lunatic Asylum (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health), Toronto (1850)

by Tara Bissett

The architectural design of mental health institutions has been dramatically affected by changing perceptions of mental illness through time. Until the mid-19th century, mental illness was hidden away in Canadian society, and it was left to family members, prisons, and so-called “madhouses” to shoulder the responsibility of caring for the mentally ill. Around 1850, mental healthcare practices throughout North America were called into question and reforms were enacted. Reformers called for humane and hygienic treatment protocols, centralized in one institution, and this movement led to the construction of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in the City of Toronto. Today, the asylum has been renamed the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and has expanded its services throughout the city. In a location that was once the southwestern edge of the growing city, the neighbourhood is now within the west end of downtown Toronto, where the institution serves as a landmark along one of Toronto’s main arteries, Queen Street West. The CAMH has borne witness to the changing conception of mental illness since the 19th century.

Social reform

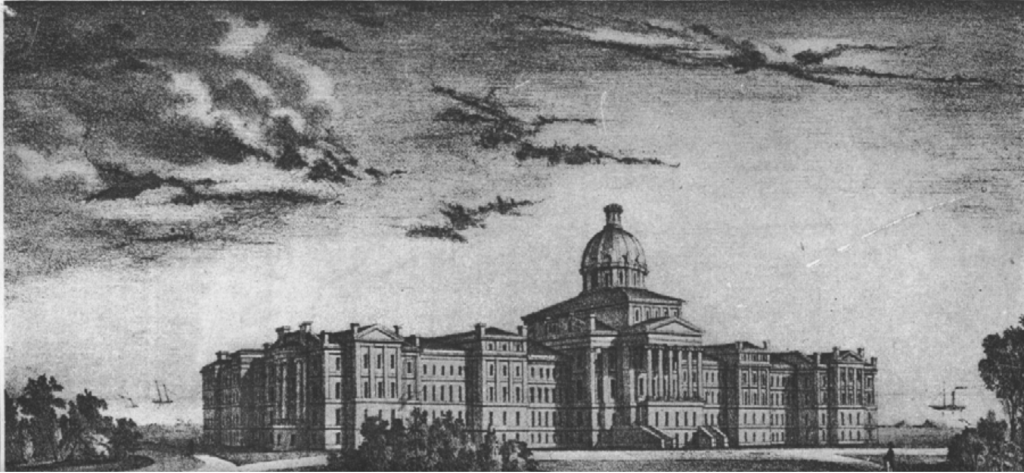

Known as “one of the wonders of the west,” the institution once held the third-largest patient population in North America and was the only permanent facility for psychiatric treatment in Upper Canada.[1] The asylum’s site comprised a monumental 20-hectare plot set in a greenery landscape. Construction began in 1846, according to the design of notable Canadian architect John Howard. As a stately Neoclassical building with a centralized dome, the design displayed the architect’s knowledge of the British National Gallery in London’s Trafalgar Square, which had been built less than a decade earlier. Like the gallery, the asylum was a public institution that drew upon the established visual authority of historical architecture. A palatial five-storey stone structure, the building’s entrance faced north, and carried an imposing classical portico atop massive columns, reminiscent of the Parthenon from ancient Greece.

Embodying social reform, the building was designed to be admired, and the asylum became a sensation shortly after its construction. Howard’s design was in line with other state-sanctioned psychiatric facilities that assumed a monumental character, capturing the collective imagination and becoming unlikely symbols of civic pride and wonder. The Provincial Asylum was associated with high cure rates, hope, and modernity, and became a popular Toronto tourist destination. Until the mid-20th century, lithographs and watercolours of the institution appeared in popular magazines and on postcards.

Program of order and control

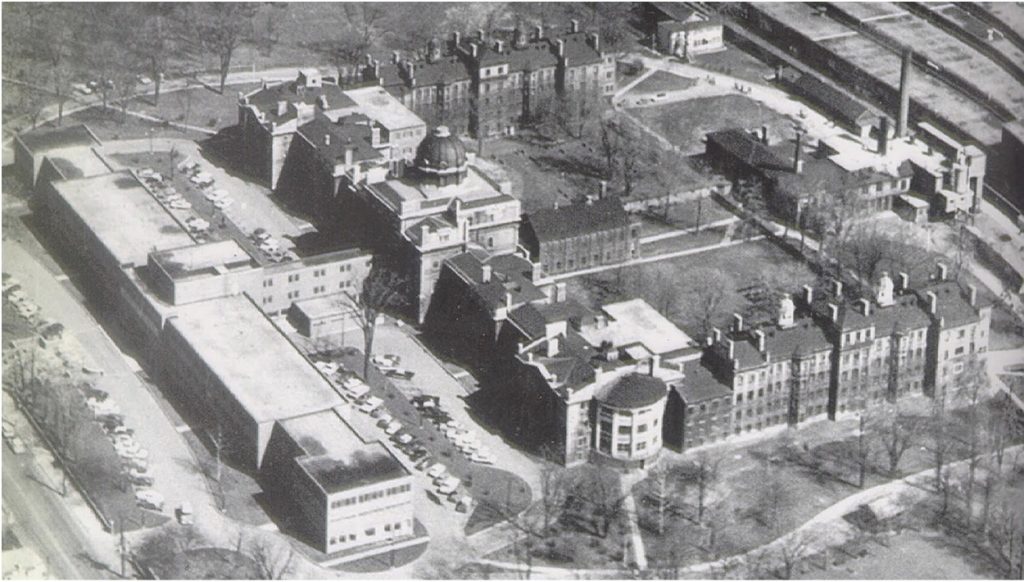

Just two decades after it was built, the institution was overcrowded, and plans to enlarge it were underway. Architect Kivas Tully transformed the complex into a U-shape by adding two four-storey wings flanking Howard’s original building.

Tully added architectural details that introduced a domestic atmosphere to the institution. He broke up the facades of the new wings to resemble rows of townhouses and inserted bay windows, which were common in late 19th-century houses. These domestic additions reflected the ethos of the interior, which cultivated the atmosphere of a Victorian home. The asylum’s corridors were long, well-lit, and unusually broad, acting as indoor pathways and inviting safe social interactions: the long sightlines would avoid startling patients with surprise encounters. The new building wings separated patients by gender, each with its own dining hall and living room area for socialization, with views of the surrounding landscape. With a role adapted to the new domestic structure of the facility, the asylum superintendent took a familial approach to his patients instead of a punitive one.[2]

However, the asylum’s plan also reflected the prevailing theories of the influential psychologist Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, who suggested that an architectural program of order and control should be anchored to the treatment protocol. Most residents were confined to rooms reminiscent of cells; patients with more severe illnesses resided deep within the wings, away from the central block and sometimes inside internal locked hospitals.[3] The central block, under the dome, was generally off-limits to the patient population and was occupied by the superintendent, the bureaucratic offices, and the chapel. The upper level of the original building contained expensive luxury apartments with Victorian verandahs. Occupied by wealthy patients, these rooms were separated from the rest of the building by stairways that went directly to the ground level and allowed for a privileged experience.

Control of patient activity was also reflected by the introduction of several outbuildings that appeared around the main institution near the end of the 19th century. These buildings included a slaughterhouse, industrial kitchen, and workshops, and were staffed by patient-labourers. According to contemporary psychology, outdoor activity and the development of skilled labour was an integral part of the curative process, although neither the patient-labourers from the asylum nor the nearby Mercer Reformatory of Women were compensated for their work. The original masonry enclosure that still stands as a designated heritage structure was built by the institution’s patients.

A new face for mental health treatment

After World War Two, the perception of mental illness changed again in Canadian society, with advances in treatments and psychotropic medicines that facilitated outpatient treatments. Asylums were no longer conceived as substitute homes providing rooms for extended stays, but instead as modern machines intended for curing mental health conditions. In turn, the building’s historical facade and monumental countenance became associated with old-fashioned practices in medicine.

Responding to these cultural changes, the institution projected a new image of mental health treatment in the 1950s. A modern, utilitarian building was built on the shared plot of land directly in front of the original institution to conceal the original Neo-Classical facade from the street. Constructed of glass and concrete, the new structure reflected treatment protocols of the modern era: impersonal, utilitarian, and unimposing.

Developing a campus-like atmosphere, the institution incorporated a community centre with stores, a parlour, and a coffee shop as its new focus, acting as a microcosm of the surrounding urban fabric. Despite heritage campaigns to conserve Howard and Tully’s 19th-century asylum that stood behind this modern building and was so emblematic of the modernity of 1850, it was demolished in 1975.

The evolution of the architectural complex of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health documents the changing perceptions of mental health treatment and the efforts to mitigate the stigma of mental illness. The institution’s process of continual reinvention was not isolated to architectural change; it was also renamed several times. Opening originally as the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, twenty years later it became the Hospital for the Insane, and later received new names corresponding to each epoch’s conception of mental health treatment. In 1979, the institution’s address was symbolically changed from 999 to 1000 Queen Street West.

Today CAMH is an important icon in Toronto’s urban landscape. The institution and its landscape was transformed again in the early 2000s to better incorporate it into the surrounding Queen West strip and contribute to the area’s revitalisation. If the nineteenth century drew upon historicized, triumphal architecture to glorify modern ideals in the centralizing of mental health treatment, and the post-war period of the 1950s used modern materials of concrete and glass to impart an institutional rationality, CAMH today blends the complex into the surrounding community, with public spaces and roads that connect the institutional facilities with the city beyond, challenging the stigma of mental illness and addiction through architecture.

About the author

Tara Bissett, PhD is an architectural and urban historian. She is an Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream, at Daniels School of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto and Lecturer at the School of Architecture, University of Waterloo. Tara’s research focuses on the history of women in architecture and the planning of cities in early twentieth-century Toronto. She is particularly interested in women professionals who were not recognized as architects in their time, but were instead streamed into fields, such as social work, administration, and general urban caretaking. Tara is on the Board of the Architectural Conservancy Ontario Toronto Branch. She is the project lead on the University of Waterloo initiative, Able, a project that aims to enrich accessibility and inclusive design in Canadian architectural curricula and post-secondary environments.

Further reading

Adams, Annmarie. Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893-1943. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Ferguson, Philip M. “Kirkbride, Thomas S. (1809-1883).” In Encyclopedia of Disability, edited by Gary L. Albrecht, 1014-15. Thousand Oaks, California, London. Sage, 2006.

Hudson, Edna. The Provincial Asylum in Toronto: Reflections on Social and Architectural History. Toronto: Toronto Region Architectural Conservancy, 2000.

Keefer, Alec. “Building Canada West.” In The Provincial Asylum in Toronto: Reflections on Social and Architectural History, edited by Edna Hudson, 83-106. Toronto: Toronto Region Architectural Conservancy, 2000.

Payne, Christopher. “Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals.” Change over Time 6, no. 2 (2016): 174–91.

“Provincial Lunatic Asylum Toronto.” Canadian Illustrated News, May 21, 1870.

Thomas, Phillip N. Harrisburg State Hospital: Pennsylvania’s First Public Asylum. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Tomes, Nancy. The Art of Asylum-Keeping: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Origins of American Psychiatry. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Vattay, Sharon Lynn. “Defining ‘Architect’ in Nineteenth-Century Toronto: The Practices of John George Howard and Thomas Young.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2001.

Yanni, Carla. The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- “Provincial Lunatic Asylum Toronto,” Canadian Illustrated News, May 21, 1870, 458. ↵

- “Provincial Lunatic Asylum Toronto,” Canadian Illustrated News, May 21, 1870, 458. ↵

- Alec Keefer, “Building Canada West,” in The Provincial Asylum in Toronto: Reflections on Social and Architectural History, ed. Edna Hudson, 83-106 (Toronto: Toronto Region Architectural Conservancy, 2000), 155-66. ↵

Neoclassical refers to the Western tradition in art, design, literature, and architecture of the 18th and 19th centuries that drew inspiration from the arts of ancient Greece and Rome. The movement is often called Neoclassicism. In architecture, it is marked by the presence of antique columns in a portico, a triangular pediment, stone facades, and antique ornamental details.

A porch that leads to an entrance of a building. It is usually supported by antique columns and is sometimes raised on a podium.

The Parthenon is a former temple within the site of the Acropolis in Athens (constructed in 447 BCE). The building has served as inspiration for Neoclassical designs.