INTRODUCTION

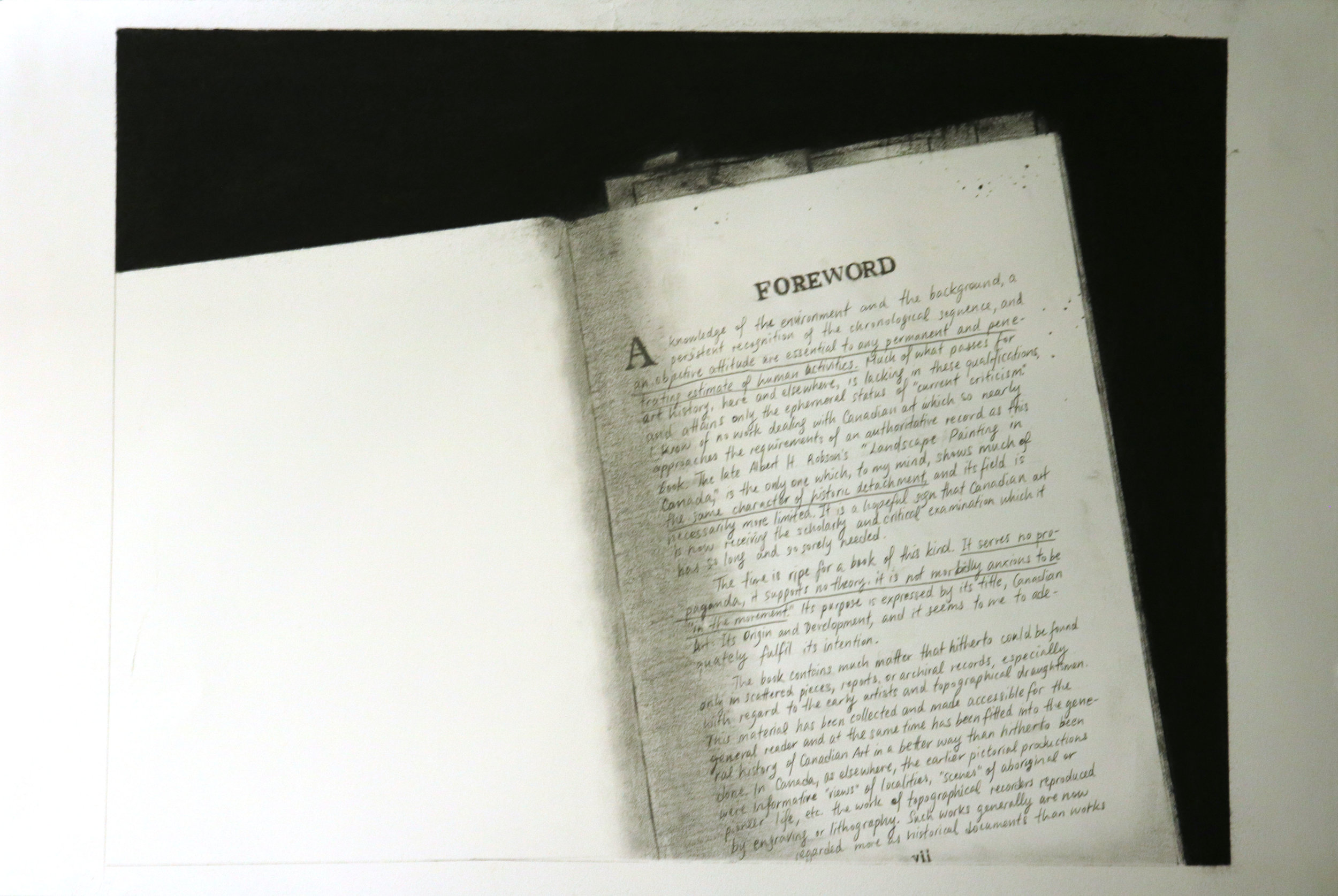

Florence Yee’s series of graphite and charcoal drawings, A History of Canadian Art History (2016), annotates and edits the “official” story of art in Canada. Each drawing reproduces and alters pages from well-known and widely available books on Canadian art, including J. Russell Harper’s Painting in Canada: A History (1991 [originally printed in 1966]), Joan Murray’s The Best of the Group of Seven (1993), and Canadian Artists in Exhibition (1974), among others. The revisions and additions that Yee makes to these books raise important questions about identity and representation in Canadian art history: Who has told the story of art in Canada? How has it been told? Who has been included? And who has been left out? Yee’s summary of the Table of Contents of Paul Duval’s High Realism in Canada (1974), for example, illuminates a significant problem in Canadian art historiography: the book is “92% male” and “100% white.”

Watch Florence Yee discuss their text-based practice and creative process in this short video.

In another drawing in the series, A History of Canadian Art History, Yee replaces the epigraph to Chapter One of William Colgate’s book Canadian Art, Its Origin and Development (1943) with their own inscription. An epigraph is a quote at the beginning of a text that summarizes or symbolizes the major subjects or themes. Colgate begins his chapter with an excerpt from American scholar Barrett Wendell, “The days of journeying are not generally days of harvest; but the seeds which fall in those pleasant times are apt to sink deep.” In Yee’s charcoal drawing, by contrast, they describe what follows as “A chapter about how Canadian art began with European settlers in 1820, almost as if there was no one here before that…” This sentence not only encapsulates the narrative arc of Colgate’s opening, but it also summarizes a larger pattern in conventional colony-to-nation histories of art in Canada. By signing their name to the epigraph, Yee, a queer second-generation Cantonese-Canadian artist based in Tkaronto/Toronto and Tiohtià:ke/Montreal, considers how their own voice relates to these stories and reveals how these stories appear from their perspective.

Under the revised epigraph, Yee faithfully transcribes Colgate’s first paragraph, which reads, “It is customary for us to confuse the birth of a national art movement in Canada with the emergence of the Group of Seven in 1919. The fact is, that Canadian art, as we know it today, had its inception at a much earlier time. It really began with. . .” Although the angle and cropping of the drawing cut off parts of the remaining passage, the names of celebrated European settler artists Paul Kane and Cornelius Krieghoff appear several times.

Colgate was not the first scholar to begin their history of Canadian art with Kane and Krieghoff. This particular origin story dates back to Albert H. Robson’s 1932 volume Canadian Landscape Painters. Most significant publications from the first half of the 20th century not only focus on the European origins of art in Canada, but also limited their study to art produced in Ontario. In one of the few recent survey textbooks on Canadian art history, art historian Laurier Lacroix recognizes that Painting in Canada: A History by J. Russell Harper (published in 1966) was “the first survey book to make an effort to provide genuinely national coverage” (2010, 417). In other words, it was not until 1966 that a book covered art from coast to coast in Canada. Yee’s series includes a drawing of the back cover of the compact edition of Harper’s book, which features a blurb describing Harper as the “‘ultimate authority’ on the subject” and calling the book “the first comprehensive survey of Cana[dian] painting from its beginnings in the seventeenth century.” Yee highlights the phrase, “ultimate authority” by bolding the text and asks the viewer to reflect on this characterization. What does it mean to proclaim someone the ultimate authority of a subject as broad and diverse as the history of art in Canada?

In recent years, there have been many more attempts to tell the story of Canadian art historiography (the way in which art history has been written by authorities in the field). In “Writing Art History in the Twentieth Century,” Lacroix articulates some of the the challenges associated with this project:

The fact that the scholarly study of Canadian art history was developing while the discipline [of art history] was being reassessed on an international level raised the issue of how historians could develop the study of Canadian cultural production when they were dealing with inadequate archives and published documentation. The lack of a nationally agreed upon corpus of iconic artworks that could constitute the basis of Canadian art history exacerbated this situation. In contrast, by 1960 there already existed more than 30 or 40 years of extensive research in a wide variety of aspects of European and American art. The significance of this was often confirmed by the marketplace, by numerous museum exhibitions, and by important publications. In Canada, however, historians had to identify and define the very body of works that constituted Canadian art. The scholarship of Gerard Morisset earlier in the century, when he had inventoried Quebecois artworks, was still relatively unknown in the early 1960s; so was much English-Canadian art writing, which was principally about landscape. Art historians were therefore doing the necessary work of discovering and documenting art produced in Canada, identifying its significance, and interpreting it at the same time, all the while taking into account the evolving criteria for the discipline of art history itself (2010, 413-4).

In the above passage, Lacroix explains that the “scholarly study of Canadian art history” developed in the 1960s. While he recognizes that scholars have been writing and teaching about art in Canada for much longer, there was a real increase in work on the topic in this decade and, at the same time, courses on Canadian art started to be regularly taught at colleges and universities. As Lacroix points out, the 1960s and 1970s were also a time when the discipline of art history as a whole was undergoing a transformation as art historians started to adopt interdisciplinary methodologies informed by feminism, Marxism, anthropology, sociology, politics, and cultural studies, among other fields, and became increasingly aware of the relationships between art, culture, and the broader social and political world.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.1

What do you think art history is? What are its subjects? What methods or practices does it involve? Can you think of any challenges that might be particular to studying the history of art in Canada?

Yee’s interventions into Canadian art texts demonstrate that they are neither neutral nor definitive. Like all scholarship, textbooks are the products of a series of decisions about what (and who) to include, what to exclude, and how these things are framed and written about. The story of Canadian art has, most often, been told through monographs. A monograph is a single-subject book written by a single author. By inserting their own voice into these monographic texts––that is, by reframing and rewriting their narratives––Yee is doing what this course also attempts to do. CanadARThistories provides materials that will help you ground and situate yourself in relation to the diverse art histories of this land we now call Canada. The course has been designed to encourage you to bring your own prior knowledge, understandings, and worldviews into the learning process. It attempts to pull apart and challenge settler-centric, linear, and colonial narratives of Canadian art history by bringing in different voices––including your own.

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- identify some of the key authors of well-known books on Canadian art history

- acknowledge the Indigenous territory you occupy

- describe the schedule, assessments, and expectations of this course

- reflect on the goals of this course and how you will achieve them

- look closely to formally analyze an artwork.

It should take you:

A History of Canadian Art History Text 10 min, Video 9 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

Course description and learning outcomes Text 6 min, Video 10 min

Guiding questions Text 6 min

Situating ourselves Text 2 min, Video 2 min

Land acknowledgements Text 5 min, Video 4 min

CanadARThistories: redefining (art) history Text 30 min

Judging a book by its table of contents Text 20 min

Close looking/slow looking Videos 3 x 10 min, Close looking journal activity 60 min

Learning journals 8 x 20 min = 160 min

Total: approximately 5.5 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 1.1 Florence Yee, A History of Canadian Art History (2016)

- Land acknowledgements: uncovering an oral history of Tkaronto, Selena Mills and Sara Roque with illustrations by Chief Lady Bird

Course description

Like the discipline of history more broadly, the writing of art history in Canada has followed (and helped to reinforce) a nation-building narrative. Since the discipline of art history formed in the 19th century, the nation and national narratives have been the overriding foundation for much art historiography. As Kristy A. Holmes notes, “From the early to mid-twentieth century, the publication of several surveys helped to consolidate the history of Canadian art as a field of study. Texts by Newton MacTavish, William Colgate, Graham McInnes, and Donald Buchanan, among others, established a narrative that linked the development of visual art with that of the colony-to-nation narrative of traditional Canadian history” (51). This colony-to-nation narrative, evident in texts such as Dennis Reid’s A Concise History of Canadian Painting (1973), remained the definitive account for students and educators for decades. Other voices have intervened since 1973; however, there is still a paucity of textbooks in Canadian art history, particularly texts that both sketch a broad history of art in Canada and respond to the pressing concerns of decolonization and diverse and inclusive representation. As researchers and instructors of Canadian art histories, we know how rich and dynamic the field is, but the teaching of art in Canada has yet to reflect this. Instructors and students are looking to break apart and challenge the canonical nature of the discipline in both course design and pedagogical practice. CanadARThistories is a new online course with associated Open Educational Resources (OER) that addresses growing concerns around inclusion, regionalism, Indigenization, and internationalization in art history curricula, and is conceived as a response to these issues. Through weekly thematic modules, the course highlights the rich visual and material culture of this land, focusing on the artistic contributions of Indigenous and settler makers.

The following video provides an overview of this course, introduces you to its creators, and explains some of the inspirations and questions behind it.

CanadARThistories: Reimagining the Canadian Art History Survey was created in an effort to showcase the rich and dynamic histories of visual and material culture in what we now call Canada. Canadian art has long been shaped by colonial legacies, regional divisions, and the canonization of national imagery.

What does this mean? It means that Canadian art history is very complex and there is no single history of art in Canada; rather there are histories plural, told from numerous perspectives, voices, places, and moments. The goal of this course is not to get you to memorize artworks—the goal is to get you thinking and talking critically about art in all its forms across Canada. By the end of this course, you should be able to walk into any museum or gallery, or flip open any book on Canadian art, and have a conversation about what you see. We also hope that you will be able to look at an object or artwork and see how it engages with ideas and histories that are often much bigger than what you see before you.

By the end of this course you will be able to:

- look at and describe art and material culture using art historical language, terminology, and methodology

- critically analyze and evaluate Canadian artworks using historical approaches and methods

- find and interpret primary and secondary sources used in art historical research including, exhibition catalogues, exhibition reviews, artist statements, and museum and art gallery archives

- articulate and support an argument about art and material objects in the context of Canada

- make connections between the images and objects viewed in class with the larger visual world

- engage in discussions about Canadian art histories in relation to decolonization, equity, inclusion, regionalism, Indigenization, and internationalization.

Guiding questions

As Dr. Cavaliere explains in the introductory video, CanadARThistories will introduce you to some of the diverse and dynamic histories of visual and material culture across the land we now call Canada. It also asks you to reflect on your own relationship to these histories and the ways in which you learn them––not only in this course but outside of it as well. Historian John Douglas Belshaw outlines the ideas behind this approach in the introduction to his Open Educational Resource Canadian History: Pre-Confederation:

Historical studies demand that we learn something about the past but it also requires us to ask how it is we know what we think we know about the past. When you read an academic history text, you’ll observe that historians typically want to prove something about events in the past. For example, they want to show that one individual played a critical role, or that environmental change was a silent but critical player, or that prejudices affecting one group had an unanticipated outcome. At the same time, however, historians are keen to prove the value of their sources. They might argue, for example, that this census record or that judicial file or some set of private correspondence offers special insights that have not before been made available.

Although it may be simplistic, perhaps too simplistic, you may find it helpful to think about the study of history as a combination of the “what” and the “how.” That is, what happened and how we know it happened.

Grappling with the Canadian past is fraught with challenges and alive with exciting questions crying out to be addressed. But what constitutes the “Canadian” past? Clearly, the geographic space we call Canada is a relatively recent invention. Confederation, beginning in 1867, spread the brand beyond the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes to include other British colonies on the east and west coasts and some of the land in between. As a political idea—a country made up of provinces and territories with a constitution, flag, anthem, etc.—it continues to evolve. But in 1867 it was just one of many colonies in the British Empire and not necessarily the pick of the litter. A century and 10 years earlier it was part of a French empire that claimed influence over a much larger territory than the Canada of today. Still another century earlier, “Canada” referred to a struggling chain of frightened and fortified settlements along the St. Lawrence.

Let’s push it back yet another century and more. Around 1567 the northern half of North America was a well-populated landscape made up of a multitude of diverse cultures. Their economies and relationships were continually changing while retaining core (and important shared) features from one generation to the next. The “Canada” of 1497—one small patch of which may have been briefly visited by John Cabot and his crew—was a vastly more populous and rich human environment than would re-emerge here until the 19th century.

So whose Canada do we study? The Canada of the French? Of the Naskapi? Of the Basque whalers with their toeholds on the east coast? Of the Nuu-chah-nulth or the Acadians? When was Canada? Are there themes we can draw across generations and centuries? Are there successions of transitions as tumultuous and irreversible as rapids on a river? Who gets to tell those stories and whose voices are likely to remain silent?

It is only by asking questions such as these that history—as an activity—can be undertaken (Belshaw 2015).

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.2

Consider Belshaw’s questions at the end of this excerpt and try to answer them for yourself: “So whose Canada do we study? The Canada of the French? Of the Naskapi? Of the Basque whalers with their toeholds on the east coast? Of the Nuu-chah-nulth or the Acadians? When was Canada? Are there themes we can draw across generations and centuries? Are there successions of transitions as tumultuous and irreversible as rapids on a river? Who gets to tell those stories and whose voices are likely to remain silent?”

Situating ourselves

In the following video, Sarah Stanners, former Curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, discusses what “the Art of Canada” means and how it might expand beyond or even challenge the national borders of Canada as a country.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.3

Please spend some time reviewing the materials provided for this course. Read the course outline, assessment instructions, learner survey, and anything else your instructor has provided.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.4

Land acknowledgments

As you will see in Module 3: Land/Scape, landscape is a historically contingent and politically powerful concept. In Canada and other colonial nations, this requires that we acknowledge the all-too-often overlooked (and erased) historical and continual inhabitation of the land on which we reside.

Please take a moment to watch the compelling land acknowledgements video (4 minutes) by Selena Mills and Sara Roque with illustrations by Chief Lady Bird, who express that: “land acknowledgements might seem like a small and simple gesture, but like many of our Indigenous ways, they are designed to evolve and hopefully hold much more meaning than the words alone—and to allow us to re-imagine the real story of this land, together.”

Consider this excerpt from the native-land.ca website:

Why acknowledge territory? Territory acknowledgement is a way that people insert an awareness of Indigenous presence and land rights in everyday life. This is often done at the beginning of ceremonies, lectures, or any public event. It can be a subtle way to recognize the history of colonialism and a need for change in settler colonial societies.

However, these acknowledgements can easily be a token gesture rather than a meaningful practice. All settlers, including recent arrivants, have a responsibility to consider what it means to acknowledge the history and legacy of colonialism. What are some of the privileges settlers enjoy today because of colonialism? How can individuals develop relationships with peoples whose territory they are living on in the contemporary Canadian geopolitical landscape? What are you, or your organization, doing beyond acknowledging the territory where you live, work, or hold your events? What might you be doing that perpetuates settler colonial futurity rather than considering alternative ways forward for Canada? Do you have an understanding of the on-going violence and the trauma that is part of the structure of colonialism?

Territory acknowledgements are one small part of disrupting and dismantling colonial structures.

Using the map at https://native-land.ca/ find where you live and note the traditional territories that you currently reside on. Perhaps you were already aware of the lands you live on. Whether or not you were, reflect on what it means to you to acknowledge the land, the territory that you occupy.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.5

CanadARThistories: Redefining (art) history

Published to mark the 150th anniversary of Confederation, the commemorative volume Art in Canada by Marc Mayer offers a new way of looking at the history of art in our country. In his essay, the former Director of the National Gallery of Canada explores the ways in which art reflects shared history and helps shape identity, while also raising thorny questions about the role of art in Canada:

Traditionally, the story of art making in Canada begins with the Baroque church decorations of the early French settlers. It cherishes the scant surviving relics of European culture as it first bloomed in the Canadian wilderness.

From the rustic efforts of seventeenth-century priests, we fade to eighteenth-century soldiers and the quaint topographical watercolours of the conquering British army. Concerning itself mostly with the successors of these pioneers, the chronicle advances to smile warmly upon the homegrown painters and sculptors, French and English, who would eventually return to Europe in search of advanced training. We celebrate the other Europeans who came to depict our already complicated young colony, its people, places and manners. The tale turns dark for a time, as the settlers paint what they mournfully took to be a last look at the new land’s ancient cultures. Soon enough though, we begin to revel in the painted vistas of the land itself and the bold prospects we appended to Europe’s grand tradition. The story marches forward, telling of our industries, our growing cities and foreign victories, while relishing the local flavours we imparted to succeeding international styles; it heralds the waning of our brief academy against unstoppable modernism; it cheers energizing liberation from old media, skills and subject matter; it applauds the exuberant experiments and the strident, reformist dissent that replaced the old ways. Finally, the rousing legend leaves us rapt in the drama of our confident present, an exciting time for a diverse community of multi-ethnic, multi-disciplinary, worldly, eclectic and autonomous professional artists whose names, at long last, are repeated beyond our borders.

The conventional art history of Canada is an optimistic adventure that should fill us with satisfaction. Unfortunately, it has problems. Aside from the constraints of space, an important difficulty we face in an art museum like ours is how to account for the present with the objects in our collections and with the sequence of artists who populate the standard narrative. Generally, art historians are preoccupied with the task of analyzing and cataloguing the work of exceptional figures from the past, the most generative of our creators, the outliers. But many of the exceptional figures of the present – such as women, Indigenous artists, Canadians of non-European descent, photographers, video artists – appear like erratic boulders on the land, unaccountable. The histories that might explain them are not part of the conventional narrative of Canadian art because canons are not inductive; they wait for brilliance and spurn the intervals. This gives the impression that much of our present culture is orphaned, while the legacies of the past are extinct. Given what we know of human nature and of how history actually works, neither can be true.

From the very first pages of our art history books, we sense trouble ahead. For example, the canonical version usually ignores the astonishing work of the highly skilled nuns who also decorated Canada’s early colonial churches, women who suffered similar deprivations and equally grave risks. They were clearly more competent in their artistry than their brethren priests who, for the most part, improvised as painters and sculptors to fulfill the needs of the Catholic ritual. The traditional division of cultural labour between men and women explains art history’s omission of surpassing talents like Marie Lemaire des Anges. Since the Renaissance, the promotion of painting and sculpture as the most serious supports for art was at the expense of the other artistic crafts, notably those practised by women and non-Europeans. This is not only a Canadian problem, of course, but it has the awkward manifestation here that places outstanding examples of Baroque embroidery in history museums, while the cruder handiwork of contemporaneous men is presented in art galleries.

More awkward still is the bald fact that artmaking in Canada does not go back a few hundred years, but untold thousands. We cannot simply dismiss this fact by calling it so much Indigenous pre-history lost in time, reducing the finest examples of continuous Aboriginal culture to the status of ethnographic material, irrelevant to the purposes of art. Nor should we accept the old-school anthropological argument that art is a recent Western invention without legitimate application to non-Western peoples. Genetics is even more recent but no one claims that geneticists invented our genes. And the scarcity of Indigenous art historians proves nothing more than unjustified neglect.

It is true that the once-superior Indigenous populations were ravaged into a small minority by the consequences of contact and colonization. It is true that their unique cultures and languages were devastated by the racism and ignorance of the settlers. The survival in Canada of Indigenous peoples, along with their cultural distinction, is a miracle that we should all hail with great relief, while forever regretting what has been lost. We must acknowledge the work of Indigenous artists past and present from across this land, makers of a living culture with universal relevance. The rich and complex Canadian scene that benefits us all, indeed that helps define us, would be unthinkable without the constant presence of Indigenous art. It must be celebrated in the pantheon of Canadian artistic genius.

In every material expression of human culture there are typical examples, and a handful of exceptional examples, that emerge from larger pools of objects. With their different missions, museums of ethnography are interested in the typical; art museums were created to honour the extraordinary. Not only do the arguments for separating the Indigenous art made in Canada from the notion of “Canadian art” smell quite musty, in my opinion they also reveal misunderstanding about the point of artmaking, identical in both cases. Moreover, they grudge the plain and easily demonstrated fact that some things, typically the products of surpassing concentration and experience, exhibit more emotional power, more refinement and consequently more beauty than other things like them. For me, such power needs hardly any context to be keenly felt.

Perpetuating the typological hierarchies of art history and the segregationist taxonomies of anthropology masks a bias against women in the first case, and against Indigenous excellence in the second. It also disconnects too many fine artists of the present from the heritage that would illuminate their work, especially in its non-traditional manifestations where links to the past are less obvious. Unfairly, this leaves them at an interpretive disadvantage and shades their brilliance.

No matter our origin or our gender, the aesthetic instinct at the root of art is the source of the empowering human perspective that helped us prosper as a species against long odds. Conveniently, it translated the bewildering mass of natural phenomena into intelligible concepts that could be expressed in shapes and symbols, patterns and pictures. Unlike science, we did not start out making art to help us understand the world; we used it to invent a world that we could understand.

Art belongs to the set of tools we humans have used to communicate, to persuade and even to dominate each other; a vehicle for myths and histories, symbols and information; an instrument of both enculturation and socialization used to build strong, centralized, coherent communities; a means to achieve collective and personal confidence. Without art, we could not have created the human sphere that has now overtaken our global habitat, and we will need it to survive our increasingly anxious triumph. From this view, the difference in the use of art, artifice and decoration between the Indigenous peoples and the Europeans who first encountered each other here so long ago can seem superficial.

In art, however, surface is everything. If their differences are superficial from a philosophical remove, few things could be more dissimilar than the surfaces of the land’s autochthonous cultures and those of the European artistic traditions that took root here four centuries ago. The will to elegant stylization governed the former, while the latter honed shifting conventions of verisimilitude. The first valued a prudent stability of forms, whereas each succeeding generation of the other sought its own. The Indigenous aesthetic focus was on the body facing the world, an outward-looking ritual of human distinction endlessly rehearsing its integration with nature. With an ethos rooted in sustainability, the First Peoples decorated themselves and their things to charm animal spirits by honouring them with the courtesy of beauty. On the other hand, the first European settlers brought inward-looking customs, decorating not so much themselves as the gilded refuges they built against a nature that they hastened to subdue and to spiritually escape; their ethos was anchored in the construction and expansion of an artificial habitat of total control, inspired by a “heavenly Jerusalem.” For Indigenous peoples, what Europeans called a “wilderness” was, in fact, the bountiful and mystical realm that constitutes the world: “What wilderness?!”

Incompatibility is the gist of this long story; would that complementarity had guided us instead. Despite their stark asymmetries, to understand Canada one needs to know both of these cultures, their differences and their influence on each other, the inclusion of many other cultures over time, and where we are now. From the perspective of a long-established cultural institution that should provide such understanding, this is easier said than done, but it is high time we broadened our perspective (Mayer 2017).

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.6

Go back and undertake a close reading of this excerpt from Marc Mayer’s essay. What are some of the key ideas and arguments that Mayer is making here? What ideas or aspects were unfamiliar to you or did you not understand? What questions do you have about this text? At the end of this course it may be useful to come back to these questions and reflect upon your response to this essay: has your understanding of it changed?

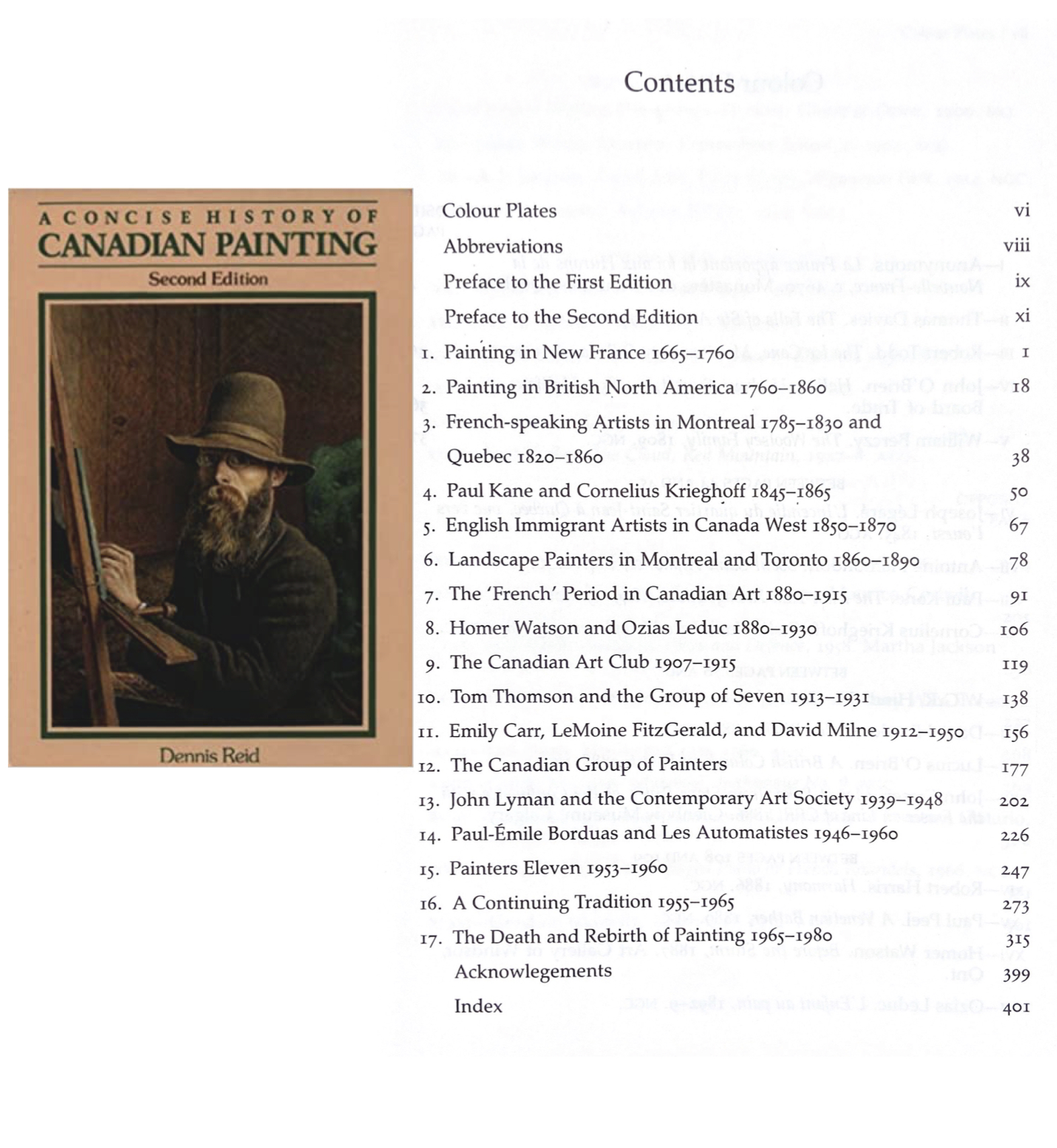

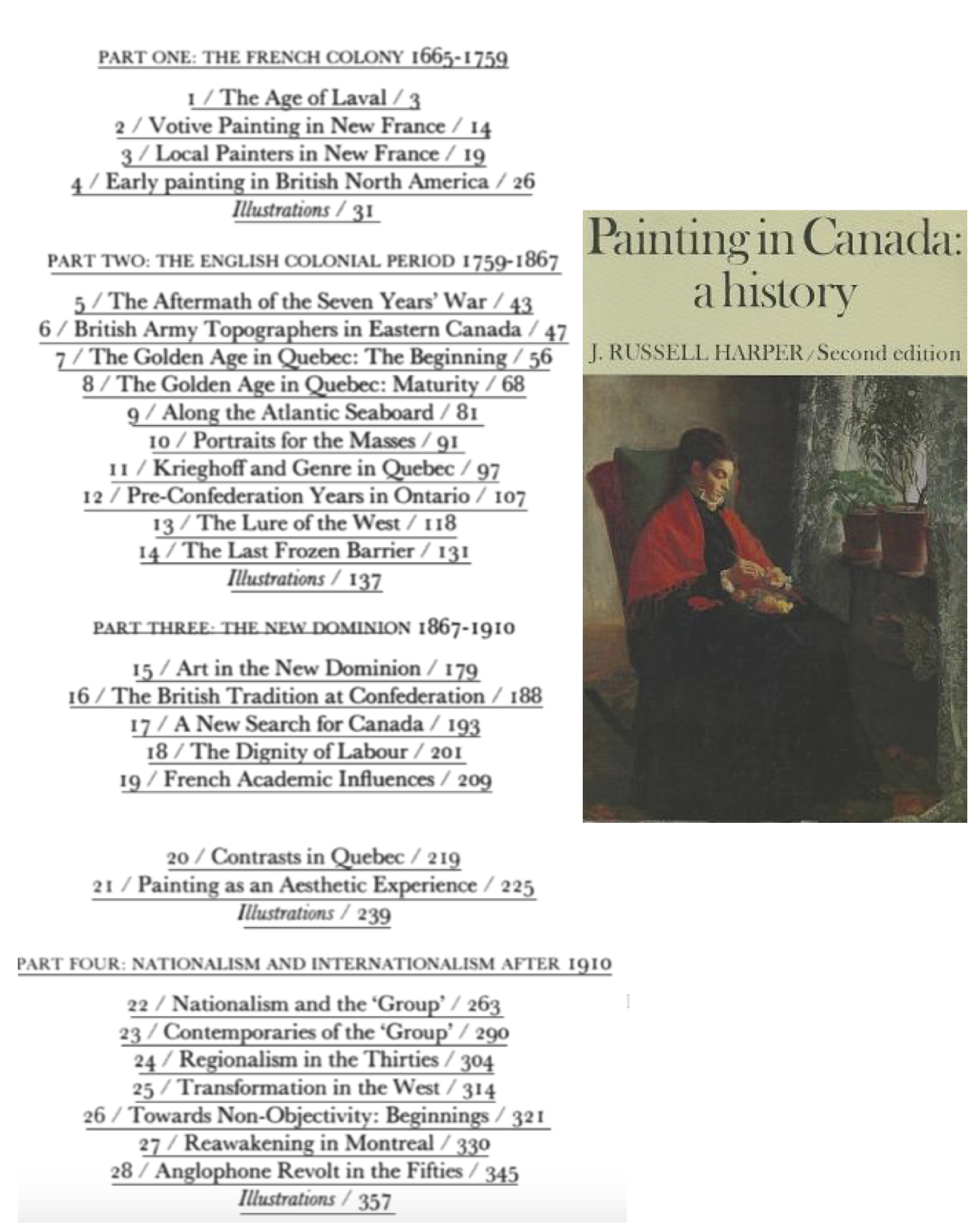

Judging a book by its table of contents

You may have heard the idiom “don’t judge a book by its cover.” It’s a cautionary phrase that encourages us not to judge the worth of something by its outward appearance. But, what about judging a book by its table of contents? A table of contents is found at the start of most reference books and textbooks, and provides a handy way for readers to navigate quickly to a certain part of a book. Unlike a book’s cover, however, the table of contents is the first indication of the way knowledge, ideas, and history is ordered by the author of a book. It can provide some clues, even before reading the preface or introduction, as to what the book is about and how a particular subject is categorized, thought about, and organized.

Most university subjects—chemistry, math, history, political science, art history and Canadian art history, for example—often rely on textbooks to introduce students to the broad strokes of the subject. In a mathematics textbook a student would be introduced to concepts and skills that slowly build on one another throughout the text. The table of contents might indicate that first you need to know about addition, before moving on to multiplication, and then finally to algebra. A history textbook might suggest to a student that they first need to know about what happened in 1841 before they can move on to learning about what happened in 1867 (in Canada that would be the Act of the Union followed by Confederation). For the purposes of introducing an entire subject to students this can be convenient, but in doing so textbooks can sometimes oversimplify information into firm categories, or at their worst exclude certain histories that might not conveniently fit into the neat categories set out by the table of contents.

In the study of Canadian art history, there have been a handful of textbooks that have been relied upon by instructors to teach students, some of which were written as early as the 1960s, that continue to be used today. Looking at the table of contents of some of these key texts can reveal aspects of the history of Canadian art history as a field of study. This history of history is called historiography. Historiography tells us who was writing about something, and when and why were they doing it. It also helps us to see the biases and subjectivities in historical thinking and writing at a given moment in time.

Judging a book by its table of contents is a good exercise in practicing historiography. For example, what might be revealed to you if a textbook has a single author versus a series of authors? Or, what is revealed when an author starts their history at a particular date or focuses on a particular place? In art history, you might also consider what type of art forms and which artists are being written about. In answering these questions you might consider aspects of gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, age, culture, and colonialism.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.7

Take a close look at the table of contents from two texts often considered “foundational” to the history of art in Canada:

Dennis Reid. A Concise History of Canadian Painting. Second edition (first published in 1973). Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1988.

J. Russell Harper. Painting in Canada: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966.

Respond in point form to the following questions:

Who is writing the text (a single author, many authors)?

When is the text written and what was happening in Canada when the text was produced?

How is the information organized (chronologically, alphabetically, geographically, by medium, by style, by gender)?

Now that you’ve thought about what is included, think about what is excluded. Are there particular forms of art, places, or people that are not mentioned?

Lastly, start thinking about what your answers to the above questions reveal to you about the history of Canadian art history (historiography). Are there biases within the study of art history? Are there problems with continuing to use these texts as the core textbook of a Canadian art history course? What might you suggest could be more useful course readings?

Slow and close looking

One of the fascinating aspects of art historical inquiry is translating what you see with your eyes, and experience with your senses or your body, into written text. This process of formal visual description leads to analysis and is a key source of evidence for making arguments about works of art and material culture. Dr. Robert Glass writes,

Art historians use visual analysis to describe and understand this experience. Often called formal analysis because it focuses on form rather than subject matter or historical context, this typically consists of two parts: description of the visual features of a work and analysis of their effects. To describe visual properties systematically, art historians rely on an established set of terms and concepts. These include characteristics such as format, scale, composition, and viewpoint; treatment of the human figure and space; and the use of form, line, color, light, and texture.

In describing visual qualities, formal analysis usually identifies certain features as contributing to the overall impression of the work. For example, a prominent linear form might suggest strength if straight and vertical, grace or sensuality if sinuous, or stability and calm if long and horizontal. Sharp contrasts in light and dark may make an image feel bold and dramatic whereas subdued lighting might suggest gentleness or intimacy. In the past, formal analysis assumed there was some elementary level of universality in the human response to visual form and tried to describe these effects. Today, the method is understood as more subjective, but still valued as a critical exercise and means of analyzing visual experience, especially in introductory art history courses (2017).

Watch the Smarthistory video “How to do visual (formal) analysis” (~10min) here to get you started:

One of the most important skills you will develop in this course is the ability to look at and describe art and material culture using art historical language, terminology, and methodology. In this section we outline how you can approach doing this. Visual formal analysis requires close looking over an extended period of time. According to the Tate Modern:

Studies have found that visitors to art galleries spend an average of eight seconds looking at each work on display.

But what happens when we spend five minutes, fifteen minutes, an hour or an afternoon really looking in detail at an artwork? This is ‘slow looking‘. It is an approach based on the idea that, if we really want to get to know a work of art, we need to spend time with it.

Slow looking is not about curators, historians or even artists telling you how you should look at art. It’s about you and the artwork, allowing yourself time to make your own discoveries and form a more personal connection with it (Tate).

The longer you look the more you begin to see. What do you see after 10 minutes? Or 30 minutes? Or more?

Here are a few tips for slow and close looking which may be helpful:

- Make yourself comfortable. Find a place, bench, stool or space on the floor that gives you a good view of the work. Feel free to stand or move around the artwork, to explore different perspectives.

- Don’t worry if nothing comes to mind at first. Be patient. Try focusing your attention on a particular detail. Try to forget any expectations, as well as anything you ‘know’ about the artwork. Keep an open mind. If you are still struggling, consider one of the following themes as an entry point: texture, colour, shape, symbols, story, perspective.

- Trust in your own authority and intuition. Pay attention to your first impressions. Don’t underestimate the reason why you were drawn to the work in the first place.

- Let your eyes wander. Your mind will try and make connections between elements of the work. These connections might be intended by the artist, or unique to you. It doesn’t matter; both are valid. See things from a fresh perspective. Make the familiar strange. Try to spot the details hiding in plain view.

- Be aware of your surroundings. Don’t try too hard to shut out what is going on around you. Don’t be put off by those squeaky shoes or the sound of visitors chatting; this is part of the fun of slow looking.

- How do you feel? Pay attention to how your mind and body respond. This might be in a subtle way. Does the art help you feel calm, does it irritate you, excite you? Does it trigger any memories?

- Share your findings. How do you feel about this artwork now you have studied it in detail? Try to summarize your thoughts. This could be in your head, with your friends, or with the strangers looking at the artwork with you.

- Look again. Try a different artwork, the same artwork, straight away, after a coffee break, on a different day. How does it look in other conditions: on a rainy day, on a bad hair day, on your birthday? (Tate)

In this video, Melissa Smith, Assistant Curator of Community Programs at the Art Gallery of Ontario, demonstrates close looking by examining a work by Canadian painter Yvonne McKague Housser:

If you are interested, Smith has another video here in which she demonstrates close looking.

LEARNING JOURNAL 1.8

- Select one artwork from the list below. Search for a full colour reproduction available online.

- Ozias Leduc, Still Life with Lay Figure (1898)

- Annie Pootoogook, Cape Dorset Freezer (2005)

- Prudence Heward, Rollande (1929)

- Bertram Brooker, Sounds Assembling (1928)

- Liz Magor, Chee-to (2000)

- Rita Letendre, Atara (1963)

- William Berczy, The Woolsey Family (1809)

- Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, The Impending Nisga’a’ Deal. Last Stand. Chump Change (1996)

- Dana Claxton, Headdress–Jeneen (2018)

- Suzy Lake, Suzy Lake as Gilles Gheerbrandt (1974)

- Set a timer and spend 10 minutes looking closely at the image.

- Make a rough sketch of the artwork. This forces you to look closely and help you understand the visual logic, various components, and content of the image.

- Formally analyze the work. Make note of what you see, when you ask:

- What are the defining features of the compositional design?

- What is the arrangement of colour, line, shape, and texture?

- What is the artist’s chosen media (oil paint, stone, sound, bronze, fabric, etc.?)

- What is the content of the image? Is it figurative? Abstract? What is being depicted?

- Consider other information easily available. Who is the artist? What is the title of the artwork? Was it given by the artist? Or a museum at a later date? What is the date of the work? Do you know any other artists or artworks from that periods you can connect it to? Does it remind you of any other artworks you have seen, from any time period?

- Reflect on your response. Does the work incite an emotion? Does the image remind you of something, or jog a memory?

- Are you able to interpret and make an argument about the artwork based on everything you have observed and considered so far? Your interpretation of the artwork should be based on an appreciation of the combined forces of form, style, and subject matter/content, together with a consideration of when the work was made. How do you make meaning from this image or object?

- Summarize your response in 500 words.

References

Belshaw, John Douglas. 2015. “Introduction.” In Canadian History: Pre-Confederation. Victoria, BC: BCcampus. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/preconfedcdnhist/chapter/1-1-introduction/.

Canadian Artists in Exhibition. 1974. Toronto: Roundstone Council for the Arts.

Colgate, William. 1943. Canadian Art: Its Origin and Development. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

Duval, Paul. 1974. High Realism in Canada. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin.

Glass, Robert. 2017. “Introduction to art historical analysis.” Smarthistory. October 28, 2017. https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-art-historical-analysis/.

Harper, Russell J. 1994. Painting in Canada: A History. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Holmes, Kristy A. 2014. “Feminist Art History in Canada: A ‘Limited Pursuit’?” In Negotiations in a Vacant Lot Studying the Visual in Canada, edited by Lynda Jessup, Erin Morton and Kirsty Robertson, 47-65. Kingston; Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lacroix, Laurier. 2010. “Writing Art History in the Twentieth Century.” In The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century, edited by Anne Whitelaw, Brian Foss, and Sandra Paikowsky. Kingston; Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Mayer, Marc. 2017. “Redefining [Art] History.” Reprinted online from Art in Canada. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2017. National Gallery of Canada. https://www.gallery.ca/collection/collecting-areas/canadian-art/art-in-canada-essay/redefining-art-history.

Murray, Joan. 1993. The Best of the Group of Seven. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Reid, Dennis. 1973. A Concise History of Canadian Painting. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Robson, Albert H. 1932. Canadian Landscape Painters. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

Tate. n.d. “A guide to slow looking.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/guide-slow-looking

The Group of Seven was a group of Canadian landscape painters, active in the 1920s and 1930s.

Historiography is the study of how history has been produced and written about, particularly through analysis of the methods and theories used and how they change over time.

Slow looking is an immersive form of study or visual analysis that encourages the participant to find meaning or knowledge in an object, often an object in a museum, over time.