LAND/SCAPE

Figure 4.1 Françoise Sullivan. Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige), 1948. From the album Danse dans la neige published by Françoise Sullivan in fifty copies, S.l. Images Ouareau (1977).

In February 1948 [Françoise] Sullivan set out for Otterburn Park, southeast of Montreal, where her artist friends Françoise Riopelle (b. 1927) and Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) lived. Dressed in a sweater, a long skirt, leggings, and fur-lined boots, she improvised Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige). The sequence of movements was vigorous, suggesting a crescendo of emotions and raw energy. In the silence of the frosty day, Sullivan’s broad gestures were echoed only by the crunching of her steps on the thick, rough layer of ice covering the snow. Riopelle filmed the performance, while Maurice Perron (1924–1999) photographed it. Perron’s iconic pictures remain the only record of the event; Riopelle’s film has been lost. The photos show Sullivan in arrested movement, her arms, legs, and torso stretching or curving expressively. Her body appears to levitate because of the lack of differentiation between foreground and background in the barren landscape (Gérin 2018).

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.1

Land becomes landscape as we experience, mediate, and develop our own and cultural understandings of it. Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige) is a physical expression of this process by which the artist uses her body to feel and understand place. Experiencing land––be it a busy city block, a quiet courtyard, or a forested mountain peak––is something that unites the spatial and the sensorial. Go outside. Listen. Feel. Smell. Move. How are you experiencing the space around you through your senses? How does your movement impact your sensation of and relationship to the space around you?

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- describe landscape in Canada as a product of historical processes, mediated by social and cultural values

- analyze the relationship of landscape as an artistic genre to nationalism, colonialism, and power relations

- identify different visual styles for representing the land as landscape

- recognize key artists and artworks produced in Canada that address landscape.

It should take you:

Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige) Text 4 min, Video 4 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

Doctrine of discovery, settlement, and territorialization Text 46 min, Video 20 min

Land into landscape Text 39 min, Video 23 min

Environment and futurities Text 24 min, Website 10 min

The land remembers Text 24 min, Website 10 min, Podcast 25 min

Learning journals 9 x 20 mins = 180 min

Total: approximately 7 hours

Key works:

- Figure 4.1 Françoise Sullivan, Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige) (1948)

- Figure 4.2 A.Y. Jackson, Terre Sauvage (1913)

- Figure 4.3 Horatio N. Topley, Vegetable display by J. Strasburgerca (1910)

- Figure 4.4 Homer Watson, The Stone Road (1881)

- Figure 4.5 Edward Poitras, Offensive/Defensive (1988)

- Caroline Monnet, Mobilize (2015)

- Figure 4.6 Lucius O’Brien, Sunrise on the Saguenay, Cape Trinity (1880)

- Figure 4.7 Elizabeth Wynn Wood, Northern Island (1927)

- Figure 4.8 Elizabeth Wynn Wood, Passing Rain (1928)

- Figure 4.9 David Milne, Painting Place III (1930)

- Isabelle Hayeur, Losing Ground (2015)

- Figure 4.10 Charles Comfort, Smelter Stacks, Copper Cliff (1936)

- Figure 4.11 Yvonne McKague Housser, Cobalt (1931)

- Figure 4.12 Edward Burtynsky, Nickel Tailings #34, Sudbury Ontario (1996)

Doctrine of discovery, settlement, and territorialisation

Land is many things: it is the ground that we rest on; it is the host and source of flora and fauna. It takes many forms, from sand to dirt to waterway, and many shapes, from deep river basins to mountain peaks.

Everyone has an experience and understanding of land. It gives us sustenance, healing, and hardship. Land can provide us with physical, familial, spiritual, and emotional connection, but it can also separate and divide us. While the land itself simply is, human understandings of the land are complex and layered. The stories we tell and the histories that play out across the land infuse it with meaning. Françoise Sullivan’s performance, Dance in the Snow (Danse dans la neige), is a playful but poignant reminder that the human meaning ascribed to land is mediated through human encounter and experience. In this way, conventions about how the land is visualized become as important as the land itself.

In Western studies of art, depictions of the land are generally referred to as landscapes. In this module, we complicate the idea of landscape as a Eurocentric mode of representation, while opening up our study to a wide range of knowledge, engagement, and representation of land. The key works in this module take us in three directions that often intersect and layer upon one another: human relationships with land as places of identity, survival, and territorialisation; the ways that humans transform land into landscape through cultural, aesthetic, and political understandings; and the ways that art can reveal and address issues that face land itself, such as climate change, consumption and waste, and resource exploitation.

The Group of Seven has occupied a central place in the Canadian art historical narrative. In part, this place comes out of the historical moment in which the group was painting in the early 20th century. Throughout the 19th century, painting in Canada was heavily influenced by European styles of art making. This makes sense, given the French and British colonial histories of the land, as well as waves of European immigration and settlement. Artists coming to Canada from Germany, for example, brought with them German Romantic modes of depicting the landscape, rich in detail and awe-inspiring vistas. Visiting British military topographers, trained in watercolour, produced sketches and notebooks replete with visual descriptions of land and settlement. Even into the 20th century, it was not uncommon for Canadian-born artists to travel to Paris or London to train in academic styles. Similarly, art displayed and sold in Canada was commonly European in either origin or style.

Much of the impetus for Canadian landscape painters in the early 20th century lay in the struggle against the dominance of European painting collected in Canada. Wealthy collectors in Toronto and Montreal often preferred to “spend $5000 on an inferior Dutch painter than $700 on a Canadian masterpiece” (Tippett 1990, 93). The “inferior Dutch painters” referred to were members of the Hague School, a designation given by the Dutch art critic Jacob Van Santen Kolft in 1875 to a group of artists active in and around The Hague in the last half of the 19th century. At the time, The Hague had not yet developed as a major industrial centre and the area provided an ideal environment for the artists of two generations to explore new ways of viewing and depicting their natural surroundings. During the “Grey Period,” the height of production spanning from the early 1870s to the late 1880s, the Hague School of painters worked in oil and watercolours to convey their intimate knowledge of the Dutch landscape and its people. The group’s muted palette of soft grays as well as browns and greens reflected the moist climate and northern environment of the Netherlands. Their preference for tonal color and an expression of a permanent peacefulness, instead of pure hues and fleeting moments, restricted these painters from identifying with French Impressionism; instead, the group has been more closely linked to the en plein-air production of the Barbizon School. As the popularity of the Barbizon School began to rise, works by Hague School artists were considered to be suitable alternatives to the increasingly scarce French works.

Although initially influenced by the Hague School during his travels through Europe, A.Y. Jackson, one of the future members of the Group of Seven, later abandoned their subjects and style for a more “Canadian approach.” Painters of The Hague School such as Mauve, Israels and the Maris brothers were emotionally invested in their own country’s landscape, not in foreign vistas. Jackson seemed uncomfortable appropriating elements of their national identity, and is considered to have matured as an artist only when he was able to articulate himself as a Canadian painter, not as an imitator of Dutch art. He became, as one art historian noted, “as artistically faithful to the Canadian landscape as the Hague School had been to their native countryside” (Hurdalek 1983, 23). Both the Hague School painters and Canadian painters at the turn of the century were nationalistically motivated, “recognizing landscape and genre scenes as an ideological and psychological vehicle for defining a nation” (Tobey 1991). The decline in interest in The Hague School helped pave the way for the rise of the Group of Seven, and their rebellion against European dominance of the Canadian arts as symbolized by the Hague School (Buis 2008).

In addition to Jackson, the Group of Seven included Lawren S. Harris (the group’s de facto leader), Franklin Carmichael, Frank H. Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, and F.H. Varley. Tom Thompson is often linked with the group, though he passed away in 1917, shortly before the group was officially formed in 1920. Emily Carr was also invited to exhibit with the group on numerous occasions; later members included Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald and Edwin Holgate.

With a shared belief that a uniquely Canadian art style could emerge only through direct contact with its natural world, the artists carried out several expeditions together to northern Ontario, where they painted the forests and lakeshores they saw as the true spirit of Canada. These excursions into Algonquin and Killarney provincial parks contributed to the notion of the Group of Seven as painting raw wilderness undisturbed by human encounter, and lent them a perceived masculine fortitude and ruggedness that seemed required to access these remote places. The irony is, of course, that they were still influenced by European art movements, particularly Post-Impressionism and Expressionism. You can read about these movements and others here.

The title of Jackson’s painting, perhaps more than the painting itself, reflects the ways in which the Group of Seven conceived of the Canadian landscape. Directly translated from French, terre sauvage means wilderness. But there is a linguistic cognate (words that sound or look similar in different languages and have a closely related meaning) to the English word savage, which comes with deeply rooted colonial connotations.

In the following excerpt from a 2007 volume, John O’Brian investigates and challenges the legacy of the Group of Seven on Canadian artistic practice:

In the painting, the heavy autumn clouds that are lodged above the open blue sky and the long, bent horizon, a horizon punctured by red and green scatterings of trees, seem as fixed and unchangeable as the granite rocks they visually mirror in the foreground. It seems to me that the balanced weight of the clouds and the rocks still the image, so that only the faint curve of the rainbow on the left side of the painting hints at the ephemeral. The quality of stilling, or of timelessness, helped the painting to become an icon, a representation of nordicity and emptiness. Terra nullius. Jackson even carried the language of terra nullius into his title, whether he intended the connection or not. (O’Brian 2007, 26)

As early as the 15th century, the Doctrine of Discovery was the legal framework that Spain, Portugal, and England used to enable colonization of land, including in North America. This international law gave license to explorers to claim vacant land, terra nullius, in the name of their monarch or sovereign. It was understood that vacant land was that which was not populated by Christians. Under this law, colonization extended beyond land to the often-violent subjugation of those who lived on it. What is now known as North America had, however, been populated by Indigenous peoples for tens of thousands of years before European colonization.

The land in Jackson’s Terre Sauvage is characterized as raw, harsh wilderness, but also empty, unsettled, and ready to be brought under colonial law. The painting emerges from and perpetuates these colonial understandings of Canadian land. Members of the Group of Seven were not necessarily painting with the Doctrine of Discovery at the forefront of their minds, if at all, but in positioning the land in this manner, their landscapes became connected to Canadian identity and the colonial histories. The rhetoric of the vastness, emptiness, harshness, and northerness of the land—think of Canada’s national anthem’s “Our true north, strong and free”—informed conceptions of Canadian identity as well as institutional and government policies. The National Gallery of Canada, for example, was eager to use the work of the Group of Seven in nation-building efforts. In his review of the 1918 Royal Canadian Academy of Arts exhibition, critic Harold Mortimer-Lamb wrote that Terre Sauvage was “one of the most important paintings of landscape yet produced by a Canadian artist, and more clearly expresses the spirit and feeling of Canada than anything that has yet been done” (NGC, “A.Y. Jackson: Terre Sauvage”).

Watch this short National Film Board of Canada documentary from 1941, Canadian Landscape, which follows painter A.Y. Jackson on his canoe trips and on foot to the northern wilderness of Canada in autumn:

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.2

How does the video talk about, characterize, and describe the land? The narrator suggests that A.Y. Jackson has engaged in a “lifelong search into the meaning of the Canadian landscape.” How does the video present Jackson’s process as an artist and how does this process shape your understandings of his paintings as they present the land? When we think about the ideas presented by John O’Brian in his analysis of Jackson’s Terre Sauvage, how might the film reinforce settler narratives of the land while minimizing other narratives?

While the painters of the Group of Seven were concerned with showing the land as wild and empty, the Canadian government was determined to demonstrate that the land was bountiful and manageable for settlement. To do this, they relied on survey photographers to use the relatively new medium of photography to document government-sponsored topographical and geological expeditions. The federal Department of the Interior was established in 1873 to administer and develop the newly acquired territories in the West. It included a Survey Branch, which was responsible for surveying and mapping land. “Photographs were used by surveyors, scientists, engineers, government officials, and even amateur naturalists as a way to inventory and process the land and its contents visually” (Cavaliere 2016, 15).

Horatio Needham Topley, a trained photographer, took his camera out of the photographic studio and onto the land, working for the Canadian Department of the Interior in 1887. Topley was the younger brother of William James Topley, who in 1872 became proprietor of a photographic studio renowned for photographic portraits. The studio photographed the dignitaries and politicians who lived, worked, and visited Canada’s new capital city, Ottawa, photographing nearly 2,300 sitters a year at its height.

A copy of Topley’s photograph above appears in one of several photographic albums compiled by the Immigration Branch of the Department of the Interior between 1892 and 1917. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Canada recruited from predominantly European countries three classes of immigrants: farmers, agricultural workers, and domestic servants. Various policies under the Immigration Act of the early 20th century both encouraged and regulated immigration, particularly of people classed by the government as well suited to Canada’s harsh winters. The albums contain photographs relating to agriculture, railroads, ports, cities, and immigration. Here, the photograph shows a carefully arranged display of fruits and vegetables. Photographs like this one circulated in Europe in order to promote immigration to Canada and were crucial tools in this process.

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.3

Describe Topley’s photograph. What do you see? How is it arranged? What is in the background? How are the people dressed? Think about what these details might reveal to you about the land. How might the government use this photograph to visually entice European immigrants to come to Canada in the early 20th century and to record successful immigration programs and policies?

Where the paintings of the Group of Seven and A.Y. Jackson depict the landscape as awe-inspiring and wild, photographs made in the same historical moment demonstrate that the land was plentiful and bountiful. It was the occupation, use, and settlement of land that justified colonial claim over land, a process often referred to as territorialization. This physical process was coupled with a sense of Canadian national identity rooted in the land: empty, rugged, and harsh. Canadians thus began to see themselves as rugged like the land, its emptiness there for the taking. Taken together, land became central to formations of settler-colonial Canadian identity which in turn helped justify colonization.

Homer Watson’s The Stone Road was painted in 1881 and combines realistic elements, a nostalgia for a simple life, and a depiction of the physical fortitude of both the land and its early colonial settlers. Art historian Brian Foss describes how Watson’s paintings address the idea of settlement:

[Watson’s paintings] depict the results of early nineteenth-century settlement by portraying nature harmoniously coexisting with the human presence. That presence could take many forms—people, farm animals, fences, crops, mills, and other buildings—but it was almost always there. Watson’s paintings are in many ways Canadian art’s most consistent and loving visual documentation of the pioneer legacy in Ontario’s historical sense of identity. Yet beneath their reassuring and often bucolic surfaces, Watson’s landscapes raise difficult questions about the history of European settlement in Canada.

In recent years pioneers and settlers have become subjects of debate. Indigenous groups around the world demand that the descendants of pioneers recognize their status as members of privileged collectives. Settler societies tend to replicate their histories and beliefs in their new communities, often at the expense of Indigenous populations that substantially predate the arrival of non-Indigenous pioneers. The Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Neutral (Attawandaron) peoples had been living in the Grand River area (including what later became Waterloo County) for centuries. Before the early nineteenth-century arrival there of the first pioneers, the British government formally granted the land extending six miles on either side of the full length of the river to the Haudenosaunee, in the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784; but First Nations title to the land continues to be disputed to this day.

During Watson’s lifetime Europeans regarded pioneers and settlers as highly admirable people who homesteaded what was considered an empty wilderness. Rather than being viewed through a critical lens, pioneers were characterized almost entirely as having traits such as resilience, resourcefulness, an immense capacity for work, and an aversion to complaining about hardships. They stood for ideals of stability and human control. (Foss 2018)

Land supports and encompasses life––the streams that flow through it, the plants that grow on it, the climate that is both generated by and alters it, and the people and animals that move across it. Art historian Keri Cronin reminds us of the importance of considering these multifaceted and interconnected aspects of land when we view art that represents land:

In one of the best-known texts in Canadian art history, Dennis Reid’s A Concise History of Canadian Painting, he describes Watson’s The Stone Road as having “tremendous strength” and suggests that “the curve of the road introduces just enough tension to keep the picture taut—frozen, as in a dream, with every iron-hard detail assuming great significance.” What is absent from this discussion, of course, is close critical attention to the animals (human and nonhuman) who travel down the road referred to in the title. What can be said, for example, about the labour of nonhuman animals in 19th-century settler-colonial societies such as the one depicted here? (Cronin 2014)

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.4

Have a look at Watson’s artworks found on the website for the Homer Watson House in Kitchener, Ontario. Watson and his sister transformed this house into a small art gallery. Select an example of Watson’s work from the website and consider Keri Cronin’s idea of labour in the colonial process of settlement. Who or what is performing labour? What kinds of labour are taking place––agricultural, industrial, domestic? How is that labour presented visually? In a calm or serene way? In a harsh way? How does the land look? Welcoming? Hostile? What might Watson be presenting or communicating about rural Canadian land?

The land that artists such as Watson portray, which has been settled, colonized, and territorialized was, and continues to be, occupied by the many Indigenous nations who have lived on the land since time immemorial. Immigration and settlement were a colonial tactic to forcibly displace Indigenous nations and communities from the land. Likewise, the myth of a raw and empty landscape presented in works like Jackson’s, which has been supported by institutions like the National Gallery of Canada as a uniquely Canadian form of art, has further perpetuated the erasure of Indigenous presence and histories on the land.

VIEW IMAGES FROM EDWARD POITRAS’S OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE HERE

Figure 4.5 Edward Poitras. Offensive / Defensive, 1988. Silver, lead, pastel, photographs. Installed at Art museum, University of Toronto.

Born in Regina, Edward Poitras is a Métis artist and a member of the Gordon First Nation, where he currently lives and works. For his conceptual artwork Offensive/Defensive, Poitras cut a rectangular strip of sod from his home on the George Gordon First Nation and another from the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. He then switched the locations of the sod, replanting the strip from the gallery lawn on the reserve and vice versa. Buried beneath each strip, Poitras cast the words “offensive” and “defensive” in lead. Poitras’s Offensive/Defensive addresses the theft of land and land rights, colonial history, the tensions between urban and rural life, and the binary of land and landscape. Read curator Gerald McMaster’s assessment of Offensive/Defensive:

Though the work was installed in two places simultaneously, it was part of a one-person show. The first part was installed just outside the Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon; the second part appeared somewhere on the Gordon Indian Reserve. The work is notably deceptive. From the photograph we see two patches of grass: Poitras took one piece of prairie sod from the Reserve and placed it on the manicured lawn of the Gallery; he then took sod from the Art Gallery lawn out to the Reserve. What was the result? The urban sod on the Reserve died immediately; but it returned to life shortly thereafter. The Reserve sod at the Gallery, on the other hand, flourished quite nicely. Offensive/Defensive plays on at least two metaphors: identity and displacement. The metaphor of identity follows this logic: one’s identity can remain relatively unaffected in urban environments; conversely, in the smaller rural/Reserve communities, identity may be more problematic than meets the eye. As well, it indicates the (un)sustainability of identities in different spaces (urban and rural). The metaphor of displacement highlights having to move from one place to another, and the sense of feeling out of place in urban environments, even though they have their advantages. […] Offensive/Defensive implies that the issues surrounding land involve a constant struggle. In Canada, land claims have become big business as aboriginal people are now gaining real estate, and in doing so, are also exercising their cultural affinities once again. In other cases, aboriginal land claims are becoming an issue for the surprised urban dweller, as urban areas are now being targeted for claims. Now the Indians are on the “offensive.” Finally, this work is about centre and periphery, saying that in fact, in every centre there is a periphery, and vice versa. For example, it used to be that reserves were the outposts, the “backwater.” This was before the identity-conscious sixties and seventies when so many young aboriginal people were wanting to “go back” to the land. This meant going to reserves and other aboriginal communities in search of identity and to be identified. In effect, they were returning to the centre. These new centres have since begun to position themselves as such. Culturally, they are flourishing. The deceptiveness of this piece renders the question of who is on the offensive or defensive, a constantly shifting one, making the work even more powerful and effective. (McMaster 1999)

Look at Edward Poitras’s Offensive/Defensive, particularly the photographic components, which were included in the 2019 exhibition In & Out of Saskatchewan at the University of Toronto Art Centre.

Caroline Monnet is a multidisciplinary artist of Anishinaabe and French heritage. Her short film, Mobilize (2015), consists of archival footage from the National Film Board and takes the viewer on a journey from the far north to the urban south, over all kinds of landscapes and conditions. As the artist writes, “Hands swiftly thread sinew through snowshoes. Axes expertly peel birch bark to make a canoe. A master paddler navigates icy white waters. In the city, Mohawk ironworkers stroll across steel girders, almost touching the sky, and a young woman asserts her place among the towers. The fearless polar punk rhythms of Tanya Tagaq’s Uja underscore the perpetual negotiation between the modern and traditional by a people always moving forward” (Monnet). Watch the film here:

According to Monnet, Mobilize is about “how Indigenous people were instrumental in shaping Canadian society, to the extent of building skyscrapers in our city. It was about saying our presence as Indigenous people can no longer be ignored” (Cunningham).

Sarah E.K. Smith and Carla Taunton’s essay “Unsettling Canadian Heritage: Decolonial Aesthetics in Canadian Video and Performance Art” describes Monnet’s work:

In a recent work, she employs the holdings of the NFB, a venerated Canadian institution that has created still and moving images of Canada since its founding in 1939. . . . Monnet’s 2015 video Mobilize (3 min.) was commissioned as part of the NFB’s Souvenir series. . . .To create the work Monnet employed a range of footage from numerous NFB titles. She sampled clips from films including well known titles such as Cree Hunters of Mistassini (1974), César et son canot d’écorce / César’s Bark Canoe (1970), High Steel (1965), Indian Memento (1967) (Janisse 2015). In working with the archive, Monnet employs techniques of montage and pastiche to intercut, juxtapose, and deconstruct archival footage, as well as playing with timing to speed up and down the original footage. . . . Mobilize foregrounds labour and movement through the juxtaposition of footage to create an open-ended and ambiguous narrative. In Mobilize, movement is both literal and metaphorical—evidenced through clips of snowshoes, canoes, boats, planes, and subways, as well as the move between the rural northern climate and the urbanized south. The idea of progression and futurity is addressed through footage of the skilled creation of heritage objects, including snowshoes and canoes. The work is a positive, upbeat and quick-paced short that brings together a range of archival footage in a manner that invokes a journey. The film employs footage that emphasizes the rhythms of and knowledge derived from the land (Janisse 2015).

A key element of the video is the soundtrack; the footage is set to “Uja,” a song by Polaris Prize–winning Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq, featured on her 2014 album Animism. “Uja” is an enthralling, rhythmic song with an increasing beat. Tagaq’s pulsating, quick breath sounds give Mobilize a sense of urgency, and the pacing of the song also echoes the physical exertion of the individuals depicted. . . .Monnet’s use of a song by a contemporary Indigenous artist, Tagaq, who employs Inuk throat singing, also helps to foreground an Indigenous world view in the video.

The pace of Mobilize is apparent from the very beginning of the film. Against a quick beat, the work opens with a focused shot of hands, grasping the frame of a snowshoe as they bind the wood together, lacing it. The footage quickly jumps to a scene of a figure shot from the knees down, walking on finished snowshoes. The video jumps back and forth between hands and use, making, moving, all flashing by in pace with the increasing tempo of the beat. Slowly the focus zooms out so that the face of the female maker and the body of the snowshoe-clad figure are visible. This emphasis on bodies and the shift between the representation of skill and mobility repeats throughout the video.

Subsequently, the viewer is presented with footage of physical labour in the woods, tasks including chopping a tree, removing bark, framing a birch bark canoe, all intercut with footage of a man paddling a canoe. Here, the vantage point of the footage is dynamic, changing from the bow of the boat (looking toward the figure), to a sightline from the perspective of the man navigating waterways (looking outwards at the water). These perspectives are fragmented because different clips have been edited together. Nonetheless, the choppy footage gives a sense that the viewer is in the boat and moving forward. Mobilize quickly covers ground from the wooded location and waterways. Next, footage shows a motorized boat approaching a northern community by water. A snowmobile covers territory on the ground as we see houses in a rural community, with clean laundry hanging on lines between the homes. Footage shows children at play, enjoying string games. Subsequently the video is intercut with images of wolves in a snowy landscape, evoking wilderness. Then we are brought back to the waterway with footage of the canoe, a disjointed journey sped up to an impossible speed, as the canoe deftly navigates the water.

As Tagaq’s song peaks, the video depicts a more urban setting evidenced by footage of ironworkers constructing a skyscraper and shots of Inuktitut syllabics being used on a typewriter. A floatplane arrives and then takes off. The now frantic pace of the song resonates with the footage of the Montreal subway, with cars arriving and departing as the clips flicker in a disjointed fashion. Near the end of the work, we see the final protagonist of the film, a young Indigenous woman with a modern short haircut, dressed in a 1960s style green dress. The woman is, in fact, one of the Indigenous women from across Canada who were trained as the hostesses for the Indians of Canada Pavilion—depicted in Indian Memento. Her inclusion is a reference to the pavilion’s history as a key site for Indigenous self-representation, activism, and social justice. She alludes to the modernity and optimism of the exposition, as well as the nostalgia and ceremony imbued in the Canadian centennial. She walks the streets of Montreal, her path interspersed with clips of urban transportation—the streets, cars, subways, all revealing the movement and vitality of the city.

As the work concludes, the video slows, focusing on the woman’s contemplative face in the city. Describing Mobilize, Monnet recounts the video as urgent and intense (Janisse 2015). In employing footage of Indigenous peoples from the NFB archives, Monnet recontextualizes representations that have lost resonance in the contemporary moment. In doing so, she creates a new narrative that speaks to possibility and futurity. Monnet explains the importance of the contemporary in Mobilize: “This is what I wanted to create: a film where people feel that Indigenous people are very much alive, moving forward, anchored in today’s reality, vibrant and contemporary” (Dam 2015 ). Specifically, Monnet explains Mobilize as a “call for action,” noting that skilled cultural production like the creation of snowshoes in the video is a means to mobilize skills, as well as bodies. In her words, “… It’s also about being capable of movement, mobilizing ourselves to keep moving forward and encouraging people to act for political and social change” (Janisse 2015). (Smith and Taunton 2018, 330-32)

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.5

After reading the previous excerpt from Sarah E.K. Smith and Carla Taunton’s essay “Unsettling Canadian Heritage: Decolonial Aesthetics in Canadian Video and Performance Art,” consider how Mobilize counters stereotypical representations of Indigenous peoples in Canada and addresses the centrality of land to Indigenous identity and colonialism. How does Mobilize make a case for cultural continuity between historic and contemporary Indigenous practices? What and whose perspectives are privileged? How is the film an example of self-determined Indigenous representation? What is the role of land and landscape in the film?

Land into landscape

If land is the actual physical earth––the dirt and rock upon which plants, animals, and humans grow––then landscape can be understood as any human construction or understanding of land. This can be seen most clearly, perhaps, in landscape as an artistic genre or subject; a means for artists to interpret the land, employing individual creativity, styles, or modes. Landscapes are as old as human history and their making spans the globe. The term landscape, however, came into use in the English language in the 17th century specifically for works of art, though it was quickly taken up as a word used to describe vistas in other creative forms such as poetry and literature.

The creation of a landscape is influenced by all kinds of collective and individual philosophical, emotional, social, and political motivations that shape the final style or form of a work. In 18th- and 19th-century European art making, dominant approaches to landscape include the Picturesque, characterized by orderly beauty, and the Romantic, characterized by awe-inspiring and sometimes overwhelming vistas referred to as sublime, and later Impressionism, a sensory study of light and colour. These styles made their way to Canada through the movement of settlers, and influenced the ways that artists interpreted the land into the Canadian landscape.

In this section, we will look at four works made between 1880 and 2015. All four works transform the land into Canadian landscape through a different aesthetic lens that has been shaped by European modes such as the Picturesque, Romanticism, or Impressionism. While all four are distinct––two paintings, a sculpture, and a film––they are all concerned in some way with qualities of form, such as light, composition, colour, and texture, and provide distinct aesthetic interpretations that turn the dirt and rocks of the land into an aestheticized and politicized Canadian landscape. It is important to point out that, while form and beauty play a large role in this process, landscape, unlike land, is not inert or neutral. Art historian W.J.T. Mitchell encourages us to understand landscape not as a noun (a thing) but as a verb (an action). In this way the verb “to landscape” connotes a particular privileging of certain ideas and perspectives over others in understanding land, and views landscape as an instrument of power:

The aim of this book is to change “landscape” from a noun to a verb. It asks that we think of landscape, not as an object to be seen or a text to be read, but as a process by which social and subjective identities are formed. The study of landscape has gone through two major shifts in this century: the first (associated with modernism) attempted to read the history of landscape primarily on the basis of a history of landscape painting, and to narrativize that history as a progressive movement toward purification of the visual field; the second (associated with postmodernism) tended to decenter the role of painting and pure formal visuality in favor of a semiotic and hermeneutic approach that treated landscape as an allegory of psychological or ideological themes. I call the first approach “contemplative” because its aim is the evacuation of verbal, narrative, or historical elements and the presentation of an image designed for transcendental consciousness—whether a “transparent eyeball,” an experience of “presence,” or an “innocent eye.” The second strategy is interpretative and is exemplified in attempts to decode landscape as a body of determinate signs. It is clear that landscapes can be deciphered as textual systems. Natural features such as trees, stones, water, animals, and dwellings can be read as symbols in religious, psychological, or political allegories; characteristic structures and forms (elevated or closed prospects, times of day, positioning of the spectator, types of human figures) can be linked with generic and narrative typologies such as the pastoral, the georgic, the exotic, the sublime, and the picturesque.

Landscape and Power aims to absorb these approaches into a more comprehensive model that would ask not just what landscape “is” or “means” but what it does, how it works as a cultural practice. Landscape, we suggest, doesn’t merely signify or symbolize power relations; it is an instrument of cultural power, perhaps even an agent of power that is (or frequently represents itself as) independent of human intentions. Landscape as a cultural medium thus has a double role with respect to something like ideology: it naturalizes a cultural and social construction, representing an artificial world as if it were simply given and inevitable, and it also makes that representation operational by interpellating its beholder in some more or less determinate relation to its givenness as sight and site. Thus, landscape (whether urban or rural, artificial or natural) always greets us as space, as environment, as that within which “we” (figured as “the figures” in the landscape) find—or lose—ourselves. An account of landscape understood in this way therefore cannot be content simply to displace the illegible visuality of the modernist paradigm in favor of a readable allegory; it has to trace the process by which landscape effaces its own readability and naturalizes itself and must understand that process in relation to what might be called “the natural histories” of its own beholders. What we have done and are doing to our environment, what the environment in turn does to us, how we naturalize what we do to each other, and how these “doings” are enacted in the media of representation we call “landscape” are the real subjects of Landscape and Power. (Mitchell 1994, 1-2)

Consider the power dynamics of landscape as a genre in relation to Lucius O’Brien’s 1880 painting, Sunrise on the Saguenay. O’Brien’s painterly style was greatly influenced by a movement that was happening in the United States called Luminism that was characterized by effects of light in landscapes, such as reflective water and a soft, hazy sky; attention to detail and the suppression of brushstrokes; and an emphasis on tranquility and calm. Luminism comes out of Romantic aesthetic traditions in that its ultimate goal was to evoke an emotional reaction from viewers.

Read Dennis Reid’s essay in Canadian Art about the importance of Sunrise on the Saguenay, Cape Trinity which entered the National Gallery of Canada’s collection in 1880, the same year the gallery was founded.

O’Brien painted locations that he passed through as he traveled westward across the newly minted Canadian nation (recall that Canadian Confederation had occurred only 13 years earlier, in 1867). Many artists in this moment worked and traveled in the same way. In part, this was because artists believed their role was to visually record the land and express something unique about Canadian identity through the land. Settler-Canadians were eager to view these types of paintings as a way to access vistas of their new (to them) country and were inspired by landscapes such as O’Brien’s that were grand, beautiful, and moving. In short, Sunrise on the Saguenay was meant to instill a sense of national pride. In fact, O’Brien is known to have remarked to Prime Minister Charles Tupper, “Suppose that instead of Exhibiting Canadian art, Canadian artists should help to represent Canada by such portrayal as they can give of the picturesque aspects of her scenery and life. Pictures and drawings of Canadian life and scenery would have in this connection, an interest due to the subject & would materially help to make the country known and understood” (NGC, Lucius O’Brien). This idea of national identity manifest through imagery of the land is seen in O’Brien’s appointment as art editor of a two-volume book project called Picturesque Canada: The Country as It Was and Is (1882), which made views of remote parts of the land even more accessible and sought after.

Engage with Picturesque Canada: The Country as It Was and Is by thumbing through the digitized pages. Pay close attention to the visual style through which the land is presented and how the accompanying text describes it.

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.6

Think about how W.J.T. Mitchell emphasizes that we should focus not on “what landscape ‘is’ or ‘means’ but what it does, how it works as a cultural practice. Landscape, we suggest, doesn’t merely signify or symbolize power relations; it is an instrument of cultural power, perhaps even an agent of power that is.” Take a close and lingering look at Sunrise on the Saguenay. Describe it formally: How would you describe it to someone who could not see it? Is it realistic? Detailed? Abstract? Ask yourself how these formal qualities make you feel: Calm? Moved? Awed? What is in the painting and from whose perspective: What kind of boats? For what might sunrise be a metaphor? Who is telling the story and what story are they telling? Think about how the formal description that you’ve provided influences the work as “an instrument of cultural power.” It is aesthetically alluring, yes, but does it tell you something about the colonial context in which it was painted? And what about its place in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada?

Lucius O’Brien’s spent his painting career exploring landscapes all across Canada. In contrast, Elizabeth Wynn Wood, who worked many decades after O’Brien was part of a larger movement that attempted to connect Canadian identity to the small geographical region of Northern Ontario.

Elizabeth Wynn Wood remarked about land and sculptural form:

Sculptural form is not the imitation of natural form any more than poetry is the imitation of natural conversation . . . While a piece of sculpture may contain visual forms with which we are acquainted by daily experience, it is essentially a design worked out by means of the juxtaposition of masses in space, just as poetry is a design wrought by the sounds of words in time. (NGC, Elizabeth Wynn Wood)

Wood lived and worked in Toronto, and was part of the close-knit artistic circle that included the Group of Seven, whose paintings had by the mid-1920s epitomized a distinct Canadian visual idiom that connected the empty northern Ontario wilderness with Canadian identity (as you have read about in A.Y. Jackson’s Terre Sauvage). Wood achieved both critical and popular success in her lifetime––not an easy feat for Canadian artists in the early 20th century! As the art critic Jehanne Biétry Salinger wrote in 1931 of Wood’s aesthetic, “The bareness of [her] style offers a unique contribution to the aesthetic life of Canada” (Art Gallery of Ontario). We can see the “bareness” of Wood’s simplified style in works like Northern Island (1927) and Passing Rain (1928). Where conservative art critics had hitherto prized an artists’ ability to achieve a physical likeness to life, Wood (like other modern sculptors such as Romanian artist Constantin Brancusi) challenged convention, abstracting elements from nature into pared-down shapes and forms to evoke the essence of a scene, object, or figure.

VIEW ELIZABETH WYNN WOOD’S NORTHERN ISLAND HERE

Figure 4.7 Elizabeth Wynn Wood, Northern Island, 1927. Orsera marble, cast tin on black glass base, 22.5 x 37.7 x 20.8 cm with base. National Gallery of Canada.

VIEW ELIZABETH WYNN WOOD’S PASSING RAIN HERE

Figure 4.8 Elizabeth Wynn Wood, Passing Rain, 1928. Carved 1929, Orsera marble, 81.3 x 107.3 x 20.1 cm. National Gallery of Canada.

Elizabeth Wynn Wood was a sculptor and teacher from Orillia, Ontario. In 1925, she graduated from the Ontario College of Art (OCA) where she studied under Group of Seven members Arthur Lismer and J.E.H. MacDonald, as well as her future husband, Emanuel Hahn. She was a founding member of the Sculptors Society of Canada in 1928 and the Canadian Arts Council, and was made a member of the Royal Academy of Canadian Arts. She spent time studying at the Art Student League in New York City, where the influence of ancient Egyptian art greatly influenced the direction of sculptures, leading to her simplified, modernist interpretation of subjects ranging from figures like Linda, munitions factory girls, and perhaps the subject she is best known for now: the landscape. After her study at the OCA she began to focus almost entirely on sculpture, rendering in three dimensions the rugged Canadian landscapes she knew best––the low-lying rock islands of Lake Couchiching and the smooth granite ridges seen along the Pickerel River, where she spent many summers.

Wood stood out for her exploration of landscape in sculptural form, combining the forms of rocks, water, and trees in her own distinctive language, using uncommon materials like tin. In Northern Island, a solitary windswept tree is perched on a single smooth rock cast in tin (which does not tarnish or rust) and placed on a sheet of black glass to suggest water. Tin as an ingredient of bronze was a typical sculptural material at the time, but using tin on its own was Wood’s innovation (LeBourdais 1945, 20).

In 1929, the stock market crash shattered the already-slim market for public sculpture and triggered the decade’s subsequent hard times. To help make ends meet, and despite laws prohibiting married women from working if their husbands could support them, Wood began teaching at Toronto’s Central Technical School in 1930. Gender informed Wood’s interest in producing works such as Munitions Worker (1944), which immortalized women’s contributions to the war effort on the home front. Wood emerged as a sculptor at the apex of the Group of Seven’s fame. In feminist terms, Wood’s landscape sculptures may have been a strategy to gain acceptance in a male-dominated art world in Canada, where landscape was by then a widely established genre. It seems that Wood believed it would be easier to establish herself by adopting popular aesthetic trends with her sculpture, and in this choice she was not alone; many artists in the 1920s and 30s explored landscape in their work because the ground had already been laid for landscape as a dominating force in art exhibitions. Comparing Wood’s work to the Group of Seven’s Post-Impressionist aesthetic, however, demonstrates that her approach to representing the land is remarkably different, her sculptures original in their own right.

Wood’s training with members of the Group of Seven, her art community, the discourse on landscape in Toronto, and her own art practice prompted Wood to engage in contemporary debates about the role of the artist in the social world, and the debates that were ramping up about landscape art versus figurative art in Canada. In a popular periodical, Forum, university professor and social critic Frank Underhill argued that the various international crises in the thirties (related in many places, like Spain, to communism and democracy) were pushing American and European artists to engage with political and communist themes in their artworks, while he felt that Canadian artists were engaged in “rustic rumination,” meaning they were not confronting the social and political realities of the world. Wood weighed in with her own article attacking Underhill in Forum in February 1937. Entitled “Art and the Pre-Cambrian Shield,” Wood argued that “one cannot view everything in terms of politics and economics,” which she considered merely the “plumbing and heating” of society (Carney 105). She defended the long-standing centrality of landscape in English-Canadian art, asking “What should we do instead? Paint castles in Spain—crumbling?” A few months later the Canadian painter Paraskeva Clark responded to Wood’s essay, taking issue with what Clark saw as an abiding individualism that could not be sustained given the socialist fights taking place around the world (Clark).

The relevance of landscape versus human-centred subjects was hotly debated in the 1930s and Wood, too, participated in such debates. The following excerpt by Lisa Panayotidis outlines Wood’s engagement with Underhill and Clark on the place of the artist in society:

Wynn Wood deemed Underhill’s comments to be not only an attack on the freedom of artistic practice and expression but specifically on a younger group of artists, who the outspoken professor in essence pronounced as isolationists, derivative, and devoid of original ideas. The artist countered with a February 1937 article in the Forum, “Art and the Canadian Shield,” in which she dismissed Underhill as “riding a presently fashionable wave, wherein the idea of art as propaganda, serving the party, diarizing current experience, is easy to comprehend and insist upon. It is a mild epidemic of the Early Christian Martyr – Communist – Oxford Group fever which demands the consecration of all talent to the services of a readily recognizable cause.” Those artists, Wyn Wood pointed out, “had some doubt about the importance of civilization.” In walking off to the “hinterland,” the Canadian artist was, according to her, seeking “reality” and expressing his/her displeasure with society, arguing that the “gadgets and the civilization . . . somehow [are] not the be–all either of life or culture.” She outlined a dichotomised separation between the city (civilization) and the wilderness (the divine), heralding the wilderness as the space that sustains the artist through spiritual stimulation and nourishment. “Therefore, it should not surprise [Underhill] . . . that the artist should remain unimpressed by the dissolution.” (Panayotidis 2022)

Like Elizabeth Wynn Wood, David Milne was a contemporary of the Group of Seven. Yet unlike the Group of Seven, Milne was not interested in creating art that evoked a uniquely Canadian style. He was born in rural Ontario in 1882 and moved to New York to study at the Art Students League in 1904. His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, when he joined the Canadian army in 1917 as a war artist and was sent to Europe to paint the battlefields in France and Belgium for the Canadian War Memorials program. As a result of his wartime experiences, Milne became withdrawn from city life, seeking out the solitude of the Adirondack Mountains in Vermont and later moving back to Ontario. Milne moved frequently and the effects of the various places he lived had an impact on his artistic practice. “In 1929, Milne returned permanently to Canada, first settling in Temagami, then Weston, then at Palgrave, Six Mile Lake, Toronto, Uxbridge, and finally at Baptiste Lake near Bancroft, Ontario. A change in place for Milne always resulted in a change of colour, form, and theme in his work” (NGC, David Milne).

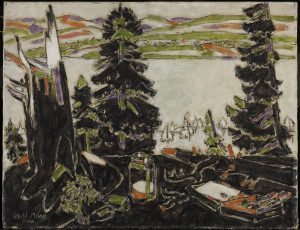

Milne’s style was influenced by Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, evident in his bold and expressive use of colour, albeit often dark or muddied. In thinking about the ways that land is transformed into landscape, Milne’s focus was not the pursuit of a national vision, but rather something that was filtered through a deeply personal lens. Milne didn’t paint the “untamed” and sweeping landscapes so common with the Group of Seven and Lucius O’Brien; instead, he painted his own lived experience of land that often show traces of the artist himself. In Painting Place III we see the artist’s tools laid out on, but inseparable from, the land. Megan Jenkin’s describes Milne’s work:

The paintings he produced after returning to Canada feel grim. He worked mostly in muddied blacks and browns, preoccupied with soil and mine runoff, and he created elaborate abstractions of the backcountry: white waterfalls, collapsed mine pits, dark reflective lakes. In all these tensions—between time spent in Canada and England, between war and peace, between life in New York and Temagami, between light and dark, colour and line—his oeuvre creates a portrait of the artist himself. His was a mind through which international visual idioms and Eastern Canadian wilderness coalesced into a Canadian modernism, important for its uniqueness and its innovation. As the exhibition’s co-curator, Sarah Milroy, noted at the opening, Milne, more than any other modern painter, taught her to appreciate the Eastern Canadian landscape—not by looking out over the horizon, but by looking straight down at muddied forest floors. (Jenkins 2018)

Balancing personal and national concerns around land, Isabelle Hayeur, who lives and works in Montreal, is known for her large digital photomontages, videos, and site-specific installations. Having lived in a suburb for some twenty years, a number of her artworks address the sad spectacle of urban sprawl and suburbia as ruins in reverse. Her approach is tied to her personal experience and draws from discourses about environmental issues and land-use planning. Losing Ground was filmed in Quartier DIX30 in Brossard, Quebec, the biggest and first “lifestyle centre” in Canada. The video reveals how local suburban and rural realities are increasingly marked by identical housing developments, retail complexes, shopping arcades and urban villages. Quarter DIX30 was designed to emulate an urban or downtown shopping experience for suburban dwellers living on the South Shore of Montreal. As well as shops and department stores, Quartier DIX30 includes a theatre, office towers, a hotel, a medical clinic, a toy superstore, and a spacious heated underground parking lot with 2000 free spaces. Hayeur critiques such urban sprawl and the resulting erosion and homogenization of rural environments. The slow pace of the film and the heightened sound mix aestheticize this otherwise banal space, proposing that this horizontal urbanization has an aesthetic allure, while simultaneously criticizing the way it eats away at landscapes and standardizes them. Watch Hayeur’s Losing Ground here:

https://player.vimeo.com/video/4709713?h=5b235706b4&portrait=0

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.7

In this section we have looked at the ways that artists transform or explore the transformation of land into landscape through distinct visual approaches that often reflect an idea, attitude, or outlook about the land. Each artist from Lucius O’Brien to Isabelle Hayeur has aestheticized the landscape, showing viewers the power and allure of the land around us. Get creative by going outside and photographing, sketching, painting, or sculpting the land that you see––a park, your balcony or backyard, the street, urban or remote spaces. Think about the decisions you are making in representing that land visually: are there people and animals? Are there elements of the built environment? What colours are you using? What is included and excluded? In a short paragraph, write down what those formal decisions might signal to you about your own understanding and relationship to the land, and how you think viewers might react to your artwork.

Environment and futurities

Canadian art and art history are haunted by romantic ideas of this land as northern, empty, and white, and in this section, we look at work by modernist painters Charles Comfort and Yvonne McKague Housser, whose representations of mining challenge this romanticism. They remind us that mining was a key component of industrial modernity in Canada, instigating the shift from an agricultural to an industrial nation. Minerals like nickel, copper, and silver were important here at home as well as being important export goods, and at the same time their exploitation was linked to profiteering, much conflict, and environmental destruction.

Public and media interest in climate change has increased exponentially in recent years. We have seen wildfires ignite across the globe, growing bigger every year, ocean levels rising, and entire ecosystems collapsing. Artists, too, have begun to turn their attention to the ways that human intervention in the land for resource extraction has transformed the landscape. Art historian Karla McManus has noted that the anthropocene is “the single most defining force on the planet and that the evidence for this is overwhelming. Terraforming of the earth through mining, urbanization, industrialization and agriculture; the proliferation of dams and diverting of waterways; CO2 and acidification of oceans due to climate change; the pervasive presence around the globe of plastics, concrete, and other technofossils; unprecedented rates of deforestation and extinction: these human incursions. . . . are so massive in scope that they have already entered, and will endure in, geological time” (McManus). In this section, we will also examine the scars of modern life on the earth in Edward Burtynsky’s large-scale photographs that inspire both awe and a sense of devastation.

Charles Comfort was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1900; he moved with his family to Winnipeg when he was 12, and then to Toronto in 1925. He was a commercial artist, landscape and portrait painter, printmaker, muralist, teacher and arts administrator. Comfort saved money to attend the Art Students League of New York under Robert Henri and Euphrasius Tucker. Working part-time for Brigdens commercial studio, he was temporarily transferred to Toronto in 1919. While in Toronto, Comfort joined the Arts and Letters Club, taking life-study classes and meeting members of the Group of Seven. Comfort visited the Group’s inaugural 1920 exhibition, which inspired him to work on landscape paintings, a theme he continued throughout his lifetime. He helped initiate Canada’s WWII War Art program and served as an official war artist in World War II, producing some of the best paintings by a Canadian artist of these events. He was one of the organizers of the 1941 Kingston Conference, a meeting of Canadian artists to discuss the role of art in society as well as other issues facing the arts at the time. Furthermore, he was a founding member of the Federation of Canadian Artists and contributed to the 1951 Massey Report, which led to the founding of the Canada Council, an organization that Comfort helped establish. After the war, Comfort served as Director of the National Gallery of Canada from 1960 to 1965. He was also a founding member of the Canadian Society of Graphic Art, the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour, and the Canadian Group of Painters, and he held executive positions in a number of arts organizations.

Comfort’s ordered landscapes bear the influence of the American Precisionists like Charles Scheeler, Joseph Stella and Charles Demuth. He was first introduced to the work of these American painters at the 1927 exhibition of the Société Anonyme at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario), an exhibition that influenced many Canadian artists, including Comfort. He was especially inspired by Joseph Stella’s futurist Brooklyn Bridge, among others. In 1932, he was commissioned to create his first of many murals for Toronto’s North American Life Building, and he later taught mural-painting at the Ontario College of Art. In 1933, he met the American Precisionist Charles Sheeler, an encounter which many suggest influenced his painting, Tadoussac (1935).

In Smelter Stacks, Copper Cliff, we see a very industrial landscape of smelter stacks at a nickel mine just outside of Sudbury, Ontario. The scene is rendered in Comfort’s simplified modernist style; the stacks––geometric minimalist vertical lines––are dwarfed by a massive and imposing sky. This was one of several panels and sketches focused on this site-specific project commissioned by Inco Limited, a Canadian mining company. In this tight composition, Comfort situates the iconic smelting stacks at the centre of the composition, with the billowing smoke dramatically filling the sky and swirling to the upper edges of the composition, highlighting both the beauty and danger of the mining industry. The painting is also in stark contrast to the commercial design work which sustained Comfort. The graphic work he produced for mining and railway companies often glorified these industries, but here the mine is offered for aesthetic consideration. Unlike the Group of Seven’s empty “wilderness,” Comfort shows viewers the industry that was pivotal to Canada’s early nation-building.

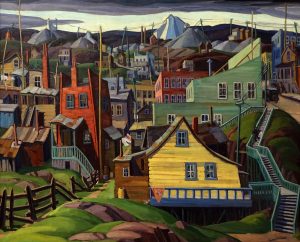

A contemporary of Charles Comfort, Yvonne McKague Housser studied at the Ontario College of Art from 1915 to 1920, where she also taught after her studies until 1949. She studied in Paris and Mexico under Hans Hofmann and Emil Bistram. Influenced by the Group of Seven’s interest in the landscape, Housser’s exploration of the genre is entirely her own. She made numerous sketching trips throughout her career, traveling to the Rockies, Quebec, Northern Ontario, Mexico and the Caribbean. Cobalt shows an affinity with the Group of Seven, with richly-coloured houses and glacier-like tailings. The artist discovered the town of Cobalt on a trip in 1917 when she was still a student and was instantly drawn to its architecture and the mining shafts you see in the background. They looked romantic to her, like a castle on a hill of slag heaps. As curator Joan Murray writes, “The town, founded in 1904, had a rough-and-ready quality. The houses, the twisting streets, the rocks set crazily on cliffs and hills, all seemed to be distributed helter-skelter. When Housser first saw Cobalt, it was still a strong producer of silver: its age of greatest prosperity was from 1907 to 1920. By 1930, its more than thirty mines were deserted, and the town a graveyard” (Murray 68). The decline of the industry captured Housser’s imagination, and she returned to the town and the subject of its mines and industry again and again.

The subject and themes in both Comfort and McKague Housser’s paintings resonate in the work of contemporary photographer, Edward Burtynsky, whose large-scale photographs of nature transformed by industry we will look at next.

Nature transformed through industry is a central theme in Edward Burtynsky’s work. One of Canada’s best-known and most celebrated photographers, Burtynsky now boasts an international reputation, in part because of the universal nature of his photographs. Burtynsky was raised around the sites and images of the vast General Motors plant in Ontario, which inspired the development of his photographic depictions of global industrial landscapes. His thought-provoking imagery explores the relationship between industry and nature. His photographs of landscapes altered by human activity, such as quarries, mines and refineries, present us with contradictions. They visually represent threats to the health of our damaged planet and our reliance on natural resources to feed our 21st-century lifestyles.

Offering an overview of his artwork, Burtynsky states:

Nature transformed through industry is a predominant theme in my work. I set course to intersect with a contemporary view of the great ages of man; from stone, to minerals, oil, transportation, silicon, and so on. To make these ideas visible I search for subjects that are rich in detail and scale yet open in their meaning. Recycling yards, mine tailings, quarries and refineries are all places that are outside of our normal experience, yet we partake of their output on a daily basis. These images are meant as metaphors to the dilemma of our modern existence; they search for a dialogue between attraction and repulsion, seduction and fear. We are drawn by desire––a chance at good living, yet we are consciously or unconsciously aware that the world is suffering for our success. Our dependence on nature to provide the materials for our consumption and our concern for the health of our planet sets us into an uneasy contradiction. For me, these images function as reflecting pools of our times. (Burtynsky 2022)

In Nickel Tailings #34, the land and nature have clearly been transformed by industry. The vibrant red river that cuts through the centre of the photograph looks like lava flowing but it is actually nickel tailings, the waste product of mining activities. Simultaneously beautiful and horrifying, this industrial scenery is a salient observation of the devastation humans can and have wrought on the landscape. The combination of beauty and horror is often present in Burtynsky’s artworks, representing a kind of industrial sublime.

The theory of sublime in art was put forward by Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). The sublime is an artistic effect that produces the strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling. T.R. Rover writes,

The sublime is understood as an aesthetic sensibility or quality evoked by an encounter with an object or phenomenon of such overwhelming power, grandeur, and immensity that it is almost beyond comprehension. The experience borders on the edge of outright terror, yet this is also combined at the same time with a sense of exhilaration and elation. Unlike other largely pleasurable or pleasing aesthetic qualities, such as the picturesque and the beautiful, there is always something intrinsically unsettling and disturbing about the sublime experience that nevertheless is also deeply alluring. (Rover 2014, 125)

Nickel Tailings #34 represents a kind of industrial sublime: a majestic scene that also provokes fear, terror, and powerlessness. Burtynsky’s photographs lure us in with their crisp detail, the repetition of patterns, highly keyed colour, and grand scale. His use of a large-format camera allows him to achieve tremendous detail. The viewer is struck by the colour, composition, and aesthetic allure of the images, while their detail and realism are chilling precisely because these are landscapes we will likely never actually see. But they are also ambiguous and contradictory: “[M]any critics wonder whether Burtynsky in aestheticizing environmental destruction is, in fact, justifying it or providing an aesthetic alibi for it. After all, many a Burtynsky print graces the walls of a corporate headquarters” (Rover 2014, 128). In his early artist statements, Burtynsky often shied away from coming across as an environmentalist or claiming that his artworks were didactic. He often suggested that he was simply presenting images of the land, leaving interpretation up to the viewer. More recently, however, Burtynsky has become more outspoken about his views on the human effects on the land and earth; no doubt this change is a by-product of seeing first-hand the damage that humans have done to the planet.

There is often a calculated distance to Burtynsky’s images; they assume a cold and distant authority, a depersonalisation. As with his larger body of work, Nickel Tailings #34 reads like a documentary photograph. The viewer is not aware of the mediation of the photographer; we are simply presented with a scene, but of course every image is the byproduct of the artist, of the maker. Burtynsky has thought carefully about his subject matter, the framing and composition, the scale, and vantage point of this image.

As art critic R.M. Vaughan has inquired:

Does Burtynsky’s rightfully admired cinematic approach…his positioning of the camera far, far away from the action captured, serve to inform, by giving the viewer a fuller picture, or does it simply distance the viewer from the action, and thus, perhaps, the acceptance of complicity? In other words, by removing the viewer from the grit, often via an elevated viewpoint, does Burtynsky’s work have an effect opposite to its apparent motivation? Instead of making us aware of how much we are part of the problem, stuff-crazed consumers that we are, does the work…in fact let us off the hook, by showing us, both figuratively and literally, that the problems are simply too big? (Vaughan)

Burtynsky’s work is neither celebration nor total denigration, and thus his photographs are deeply complex ruminations about the ruination of the planet. Nickel Tailings #34

, unlike the modernist representations of industrial progress by Charles Comfort and Yvonne Housser, shows us the unsettling reality of a landscape scarred by our consumer desires and needs.

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.8

Explore Edward Burtynsky’s artworks included in the online exhibition Footing the Bill by Art for Change here. Pick one of the “ACT” engagement activities on the website, and in 150-200 words describe whether or not Burtynsky’s artwork prompted you to want to take action, and reflect on the environmental issue and activity that the ACT button asked you to do. Consider your own reaction to Edward Burtynsky’s presentation of landscapes devastated by industry, global consumerism, and electronic waste. Do you find them captivating images? Would you have reacted differently if the images were more ruined and less visually seductive? How can we reconcile our desire for modern conveniences of mass-produced goods with our concern for environmental destruction? What can images do to help us understand the current debates that are circulating about the brand-new epoch we have brought about?

The land remembers

Watch Anishinaabe artist Bonnie Devine speak about her sculptural practice, her relationship to land, and the ways that land carries histories with it.

This excerpt from Amber Hickey’s essay “Rupturing settler time: visual culture and geographies of Indigenous futurity” discusses Bonnie Devine, ecological memory, and land:

Bonnie Devine is an artist based in Toronto and the Founding Chair of the Indigenous Visual Culture program at the Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCADU). Devine explores othered temporalities through very different means––primarily sculpture. Devine is known for her incorporation of story and longstanding Anishinaabe materials and practices into her work, much of which explores the impact of uranium mining on her home, the Serpent River First Nation. The Serpent River First Nation is situated along the Canadian Shield, which comprises some of the oldest stones on Turtle Island. These stones, shaped over billions of years, are highly contested. They are sites both of Anishinaabe teachings and of mineral extraction (Devine, 2017). Devine grew up with an awareness of the tensions between these two qualities of the stones. When I asked her what the legacy of uranium mining at the Serpent River First Nation looks and feels like, she responded by sharing an experience from when she was five or six years old. I quote Devine at length here, as this experience continues to shape her artistic approach and interests today:

[W]e were driving along the Trans-Canada Highway, Highway 17, which cuts right through our territory and our reserve. And I remember seeing on the side of the highway a giant pile of yellow powder––a giant pile of yellow powder. And all around the pile of yellow powder, the ground had been burned black. The very rocks were burned this charcoal black, and it was a really beautiful image because the color of the pile of powder was electric yellow. I had never seen a color like that before. It was accentuated further by the fact that it was surrounded by this black background, it was like a triangle against this black background. It looked like a drawing. And I really do believe that it was seeing that drawing-like landscape that made me an artist. It made me begin immediately to attach meaning to image, and to seek meaning in images. And that was early on. I remember asking my grandfather who was driving his pickup truck what that was, and he wouldn’t tell me. It became this mystery that I held close. And I remember they put me to bed that night and I’m lying there, and the silence up there is immense––we didn’t live in the village of Serpent River, we lived along the river in a house that was isolated from everything else and surrounded by forest, hills, and just a little dirt road that you got to that house by. And I’m lying there in the dark in my little bed and I remember making a promise to myself that I would find out what that was, and that I would tell the story of that. And I did find out what it was, it was sulfuric acid, and that’s why it was burning the land around the pile. The sulfuric acid was used in the refining process for the raw uranium ore.

This sulfuric acid wreaked havoc on the Serpent River First Nation. The water became unsafe, and the community is still on a boil-water advisory. The pow wow grounds are no longer useable as they are directly adjacent to the sulfuric acid plant. Dancers were unable to use their moccasins after three days of dancing––they were covered in holes burnt into the material by the sulfuric acid (pers. comm., October 5, 2017). Devine’s mention of the devastating impact of sulfuric acid surprised me to an extent, because she had not yet mentioned the impact of the uranium tailings. This, I believe, is evidence of the breadth of challenges this extractive project continues to present to the Serpent River First Nation. Regulatory systems to ensure the safety of small communities are lacking across Turtle Island. The number of communities with unmarked uranium tailings ponds is astounding, until one reflects upon the capitalist, white-supremacist, colonial foundations on which all of these projects were put forward. This is clearly the intended outcome within this violent framework.

Letters from Home is a sculptural work created in 2008, part of a broader project called Writing Home. Letters from Home comprises four glass casts of stones within the Serpent River First Nation. As mentioned before, these stones are known for being some of the oldest in Turtle Island. Amid the controversy in the Serpent River First Nation regarding the legacy of uranium mining, Devine wondered what these stones, these elders, would say of the matter. Could she find a way to make the arguments of the stones visible and legible? Devine decided to take casts of the stones, and consider them as texts or messages. In this act, Devine also framed the stones as elders, questioning Western notions of agency and expertise….

Devine qualified Letters from Home, noting that though it may seem metaphorical, it should be taken seriously:

When I speak of the land as containing a narrative, it’s not really an abstraction. It really is this idea that in fact the land remembers. And where our faulty human memory fails, the rocks actually contain a record. And of course it’s imaginative and it might strike some people as fanciful. But for me it’s deadly serious (pers. comm., October 5, 2017). (Hickey 2019, 172-77)

Engage with works from Bonnie Devine’s Writing Home in an exhibition at Connexion Artist Run Center in New Brunswick. Be sure to click the link to view the PDF exhibition catalogue. https://connexionarc.org/2008/01/25/writing-home/

LEARNING JOURNAL 4.9

Listen to “Where is the Land in Landscape?” Episode 12 of art historian Linda Steer’s podcast Unboxing the Canon (25 min, 39 sec). Steer’s podcast reflects many of the tensions between beauty and power in landscape that we have encountered in this module. It also situates differences between Eurocentric and Indigenous understandings of the land. For example, Steer discusses the idea that European landscapes can be seen as invitational, in which the viewer can enter the work and are an extension of colonial processes. This idea contrasts with some Indigenous-made landscapes that can be seen as anti-invitational in the ways that they deploy strategies to block a viewer’s entry into the work and to resist colonial processes. Bonnie Devine’s work resists colonial processes in her understanding of the land as holding memories of human and environmental stories––for example, the way the land scars from climate events. The land remembers and the land listens. Steer ends the podcast thinking about Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore’s artwork Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother (1991), a large wooden megaphone used to speak to the earth. Steer imagines what she would say if she could walk up to the megaphone and speak through it, addressing the earth. Write down what you would say if you had the chance to stand in front of Speaking to Their Mother.

OBJECT STORIES

- Elizabeth Cavaliere on William Notman, Ice Shove, Commissioner Street, Montreal (1884)

- Mark Cheetham on Noel Harding, Elevated Wetlands (1997-1998)

- Isabelle Gapp on Franklin Carmichael, Grace Lake (1931)

- Hana Nikčević on Rebecca Belmore, Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) (2017)

- John O’Brian on Robert Del Tredici, Stanrock Tailings Wall, Elliot Lake, Ontario (1985)

References

Art Gallery of Ontario. 2020. “A Landscape of Her Own.” AGO Insider, May 5, 2020. https://ago.ca/agoinsider/landscape-her-own.

Buis, Alena. 2008 “Ut pictura poesis: Edward Black Greenshields’ Collection of Hague School Paintings.” MA Thesis, Concordia University, Montreal.

Burtynsky, Edward. 2022. “Exploring the Residual Landscape.” Edward Burtynsky. https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/about/statement.

Carney, Lora Senechal. 2010. “Modern Art, the Local, and the Global.” In The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century, edited by Brian Foss, Anne Whitelaw, and Sandra Paikowsky. Montreal; Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Cavaliere, Elizabeth. 2016. “Now and Then: Situating Contemporary Photography of the Canadian West into a Shared Photographic History.” Imaginations 7(1): 14-21.

Clark, Paraskeva. 1937. “Come Out from behind the Pre-Cambrian Shield.” New Frontier 1, no. 12 (April).