ENCOUNTER

The handknit sweater shown here was made by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 2010, to be worn by Team Canada athletes at the Closing Ceremony of the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics. Made of chunky wool, the sweater features a zipper closure, garter-stitch shawl collar, and distinctive bands of patterning in black, white, gray, and red. The design—with two large elk heads on the front and the word “CANADA” across the back as well as a ribbon of maple leaves on the lower border—almost appears “pixelated,” an artefact of the knitted stitches used to produce the garment.

While similar to other mass-produced sweaters and to other Olympic gear featuring national emblems, this Hudson’s Bay sweater was considered controversial at the time of its production. Some accused HBC of cultural appropriation, pointing to the stylistic similarities between the garment and what is known as the Cowichan sweater, a type of wool sweater made with thick yarn in natural colours of black, white, and brown by the Coast Salish communities in and around Vancouver Island since at least the early twentieth century. In this sense, the Cowichan sweater is a relatively recent manifestation of Coast Salish expertise in working with wool. For centuries prior to European contact, Coast Salish women were renowned for their production of handwoven blankets, which not only fulfilled daily and ceremonial needs, but were also one of the most valued mediums of exchange between Indigenous communities.

As an object, the HBC sweater underscores the complex relations between Indigenous and settler peoples in Canada and, more broadly, the vexed objects that arise when disparate cultural groups encounter and interact with one another. Such encounters are embodied in the sweater for, according to Sylvia Olsen, they are a “material expression of the junction between two cultures, a fusion or a hybridization of European and indigenous [sic] art and craft” (2016, 16).

Canadian art history has often focused on a version of Canada as a nation founded on European settlement and trade, advanced by taming the “wilderness,” eventually gaining independence and national pride through military contributions and an embrace of multiculturalism. However, Canada’s history is complex, based on a violent history of colonialism, the government’s perpetration of racial injustice, and the view that the natural environment was, and is, solely for extraction and economic gain.

In this module, you will examine a series of case studies which demonstrate how art and visual culture reveal some of this complex history which includes interconnected relationships, cultural transfers, and translations. An early bandolier bag—a bag carried by European soldiers to store ammunition—can offer insight into early colonial encounters between French, British, and Indigenous peoples, while a contemporary “digital intervention” by Sonny Assu reframes our understanding of colonial-settler art and makes a claim for Indigenous futurity.

This module also examines the legacy of colonial encounter in Canada. John Ralston Saul has noted that a good part of Canada’s history is marred by the refusal to accept the ongoing role of Indigenous peoples in shaping Canadian society, in “Each way you turn, the roots of the Canadian idea are tied up in Aboriginal concepts and methods. That is the past, but it is also the present and the future” (2002). Objects and artworks can help us understand these roots by telling us stories about colonialism, migration, race, and gender, and their lasting legacy in the present.

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.1

Find an object in your house. Write three or four sentences about how it is the manifestation of encounter. Consider how it reflects a hybridization or conjuncture between cultures or cultural practices.

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- recognize the impact of early contact and settlement on people and land

- discuss the form, content, and context of contemporary artworks dealing with the legacy of the colonial encounter

- define the term “salvage paradigm” and correctly apply it to a discussion of key artworks

- analyze the complex connections between people, cultures, and ideas revealed by works of art and visual culture.

It should take you:

Team Canada Sweater Text 6 min

Outcomes and contents Text 110 min

Objects of encounter Text 28 min, Video 4 min, Video 7 min

Visualizing encounter Text 23 min, Video 3 min

Legacies of colonial encounter Text 46 min, Video 1 min, Video 4 min, Video 13 min

Learning journals 11 x 20 min = 220 min

Total: approximately 7.75 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 3.1 Hudson’s Bay Company, Team Canada Sweater (Vancouver Olympics) (2010)

- Fig. 3.2 Winnebago (possibly), Bandolier Bag (1880s)

- Fig. 3.3 Barry Ace, trinity suite: Bandolier for Niibwa Ndanwendaagan (My Relatives); Bandolier for Manidoo-minising (Manitoulin Island); and Bandolier for Charlie (2015)

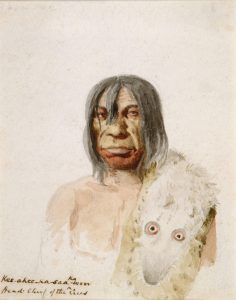

- Figs. 3.4a Paul Kane, Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow (1846) and 3.4b Paul Kane, Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow (c. 1849–56)

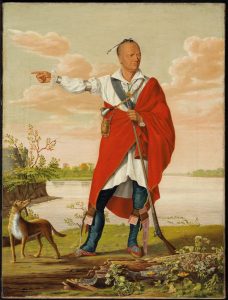

- Fig. 3.5 William Berczy, Joseph Brandt (Thayendanegea) (c. 1807)

- Fig. 3.6 Ruth Cuthand, Trading: Smallpox (2008)

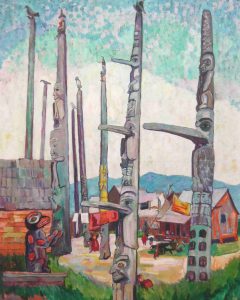

- Fig. 3.7 Emily Carr, Totem Poles, Kitseukla (1912)

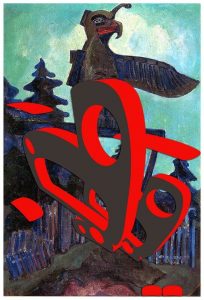

- Fig. 3.8 Sonny Assu, What a Great Spot for a Walmart! (2014)

- Fig. 3.9 Brendan Tang, Manga Ormolu Ver. 5.0-x (2020)

- Fig. 3.10 Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #16 (2004)

Much of the art historical analysis in this module is based on a basic understanding of complex historical events. For a broad chronological overview of key events and developments in Indigenous history in what is now Canada, please read and review The Canadian Encyclopedia entry Timeline: Indigenous Peoples.

You might also be interested in The Canadian Encyclopedia‘s Timeline of 100 Significant Events in Canadian History.

Objects of encounter

Mary Louise Pratt describes the “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other” as contact zones. These are spaces, she argues, characterized by “highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths, as they are lived out in many parts of the world today” (1991, 34). The objects and artworks under consideration in this module point to this idea of contact zones. They reveal the networks and relationships of exchange—often inequitable relationships—that form part of the history of visual culture in what is now Canada. The often-violent colonization and eventual permanent settlement of Canada required cultural exchange, negotiation and trade from the outset. Some artworks and objects, like the heavily beaded bandolier bags or Paul Kane’s portraits of Indigenous people, point to the ways that disparate cultures met and attempted to come to terms with each other.

Resistance to colonial power and transculturation have always been a part of Indigenous culture, and these processes are acutely visible in the work of many contemporary artists like Ruth Cuthand, Sonny Assu, and Brendan Tang. Pratt defines transculturation as the “processes whereby members of subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted by a dominant or metropolitan culture” (1991, 36).

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.2

Consider different perspectives on the idea of encounter. In what ways do you encounter other cultures in your life? Are there examples from your experience in which you have noticed disparate cultures “meet[ing], clash[ing], and grappl[ing] with each other”?

Bandolier bags are relatively large, very heavily beaded pouches or bags made from cotton, wool, velvet or leather and worn diagonally on the body like a messenger bag. They were beaded using glass beads, a trade good introduced by European settlers and which, in the mid-1800s, replaced the traditional porcupine quillwork in popularity, because they were easier to find and use, and were available in a greater variety of colours. The bags originated with Indigenous groups in the Eastern Woodlands/Great Lakes area of what is now Canada and the United States, and were modelled after European military ammunition bags. Women made bandolier bags, sewing thousands of glass beads over the entire surface of the bags. In Anishinaabe, these bags are called aazhooningwa’on, which means “worn across the shoulder.”

Watch the short film “From quills to beads: the bandolier bag”:

For contemporary artist Barry Ace, bandolier bags continue to be dynamic media for exploring intersections of tradition and technology. Honouring his Anishinaabe roots, his recent works incorporate reclaimed and salvaged electronic components that at first appear to look like Woodland-style beadwork. He explains,

It’s an introduction of a new technology, very much like beads when they were introduced to North America . . . It shows that our culture has never been in stasis. We’ve always been moving forward and are not stuck in an anthropological past, but are always looking for new ways of cultural expression (Deer 2019).

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.3

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) has many bandolier bags in its collection. Search the ROM’s collection here to find a bag. Based on what you have learned from the previous essay and video, describe the form, content, and possible context of your selected bag.

As a result of encounter during the 18th and 19th centuries, aspects of both European and Indigenous tastes, styles, and materials led to increasingly hybrid garments. The following video discusses how trade networks and exchange are reflected in an Anishinaabe outfit collected by a British Lieutenant that dates to around 1790.

Let’s look at another outfit that addresses issues of encounter and trade. O’Halloran’s Outfit was originally given to Captain Henry Dunn O’Halloran by Mi’kmaq chief Joseph Maly Itkobith as part of an honorary-chief ceremony on the banks of the Miramichi River near present-day Esgenoôpetitj First Nation. The outfit consists of a blue frock coat with silk appliqués, encrusted double-curve beadwork, blue cloth leggings, beadwork moccasins, a tobacco pouch in the shape of a beaver with four red cloth tabs covered with beadwork, and a beaded hood with a Union Jack and gold braids on both sides. It is assumed that three or more unidentified Mi’kmaq women contributed the needlework on the garments. After O’Halloran’s tour, the coat was taken back to England and remained in the possession of the O’Halloran family until 1977, when the Captain’s great-great-granddaughter put it up for auction in London, England. It was purchased by the Canadian Museum of History. In addition to the textile pieces, the outfit came with two parchment scrolls O’Halloran created in commemoration of his adoption ceremony into the Mi’kmaq nation. O’Halloran’s outfit is another example of early material culture whose visual details reveal cross-cultural exchange.

Visualizing encounter

The watercolour sketch and oil painting you see here, both entitled Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, Plains Cree, are evidence of the encounters the artist Paul Kane had with various Indigenous peoples during his years of travel across Canada. While out in the field, Kane produced sketches as you see on the left, and later, back in his Toronto studio, he developed these sketches into a cycle of one hundred oil paintings on canvas, an example of which you see on the right. While Kane’s sketches and journal writings capture what he saw with some accuracy, later in his studio he often modified his sketches to conform to a more Romantic ideal.

Kane is a complex artist whose artworks offer a compelling entry point for considering the encounter between Indigenous peoples and early settler artists and explorers in the 19th century. His remarkable travels in the Northwest at a time of great transition (particularly for Indigenous peoples across Canada) and his visual record and written observations of First Nations and Métis peoples reflect the prevailing attitudes toward Indigenous peoples held by white colonial settlers in the mid-19th century.

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.4

Compare and contrast the watercolour and oil versions of Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow. Consider what the sitter is wearing. What do the clothes tell you about the sitter? How much European influence do you see? What in the sketch leads you to this conclusion? What has changed from the original field sketch to the final oil painting? Why do you think Kane made the changes he did?

Paul Kane was born in Ireland in 1810 and arrived in Toronto with his parents as a young child in 1819. After his studies, he began working as a decorative painter in a furniture factory. He later made a name for himself with a studio on King St. in Toronto where he worked as a coach, sign and house painter, since it was challenging to make a living in Canada simply as an artist. In 1834 he left for Cobourg on the shores of Lake Ontario, where he began his long career as a portrait painter and married Harriet Clench. In 1836, he travelled around the US, eventually finding himself in Mobile, Alabama, where his reputation grew enough that he was featured in the local newspaper. In Mobile, he managed to raise enough money to travel to Europe. In 1841, and for the next four years, he ventured to France and Italy, visiting museums and copying the old masters, essentially teaching himself by copying and studying the great works of art’s past. After four years of European study, he returned to North America by way of Switzerland and London, where an encounter with the work of the American artist George Catlin changed the course of Kane’s career.

Paul Kane has also been an inspiration for contemporary artists. In the following video, more contemporary painters and artists talk about their engagement with Kane’s work:

In Arlene Gehmacher’s analysis of Kane’s oeuvre she identifies the salvage paradigm to be one of the major critical issues in his work. She explains:

Kane’s mission to record the life of Aboriginal peoples of the Northwest has all the hallmarks of what later became known as the salvage paradigm in which a dominant society attempting to save through documentation the culture of another that it considers to be at risk of vanishing. This motivation is particularly clear in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery project, created in direct response to the U.S. government’s agenda to remove the Aboriginal people to reservations. Although Canadian policy was less overt, this idea did have currency in Canada and was mentioned in 1852 in the context of an exhibit of Kane’s paintings. (The Provincial Exhibition). Kane’s attitude seems to have supported the salvage imperative as he accepted the inevitability of the Aboriginal peoples’ demise caused by the relentless encroachment of Western civilization.

Yet a conundrum lies at the heart of Kane’s work. Contemporary critical analysis pegs Kane as an appropriator who profited from picturing the lives of disempowered indigenous peoples, and even as a racist who failed to adequately respect the cultures he encountered and portrayed. However, Kane did make copious detailed and accomplished renderings of individuals and their thriving and vital culture. His work has no photographic parallel, for no one had yet turned a camera on the prairies and beyond. Kane thus built an enduring and valuable primary visual record of a culture that we otherwise would not have (Gehmacher 2014).

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.5

Define “salvage paradigm” in your own words. Can you think of other examples where this theory can be applied?

Paul Kane and other artists, including George Catlin and Cornelius Krieghoff, participated in the salvage paradigm by freezing Indigenous peoples in time. Viewers at the time, and for decades to follow, viewed Kane’s paintings as official, truthful documents that communicated accurate information about Indigenous communities and peoples. However, Kane romanticized his sitters and created historically inaccurate portraits of the peoples he saw on his travels. As Diane Eaton notes, “It was Kane’s custom in the studio oils to embellish the subjects of his field sketches with Native regalia––feathers and war bonnets, pipe stems, bear-claw necklaces, and elaborately folded buffalo-skin shirts––regardless of band or tribal origin, in order to recast them as Europeanized icons of the Romantic ‘noble savage.’ Europeans wanted mythologized depictions of North America’s Native people that dramatized them as proud, independent, virtuous, and manly” (Eaton xi).

Kane’s paintings should be viewed as emblematic of the colonial power that European settlers had in the process of representation, a colonial power intimately linked to the violent conquest of land and territory in Canada. Let’s turn now to one of Canada’s first professional portrait painters and his interpretation of the famous Mohawk leader, Thayendanegea.

The story of Western art-making in Canada—that is, paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures—begins to unfold as soon as contact and permanent settlement begin in the 15th and 16th centuries. However, it was not until the 18th century that portraiture as a genre–in particular secular portraiture–took hold in Canada. As the country’s forests turned into farms, and towns and cities grew, artists who had initially created art for churches began to turn their attention to the people who had been living here and who were slowly immigrating to Canada.

William Berczy was in many respects Canada’s first successful professional portrait painter. A German-born painter and the son of a prominent diplomat, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Austria in 1762 and exhibited with the Royal Academy in London. He came to Canada as overseer of a group of German settlers who were headed for upstate New York. Arriving in Upper Canada, York in 1794, Berczy was active in real-estate speculation for the next three years, designing and constructing some of the earliest buildings there and becoming known as a gentleman-painter. Business difficulties forced him to leave, and he eventually settled with his family in Montreal, Quebec in 1804 where he decided to make a living from his skill as a painter and architect. A community the size of Montreal offered opportunities for portraitists that were unmatched elsewhere in Canada, and the city benefited from a number of accomplished portrait painters in the 1700s. Most of his patrons were French-speaking, but Berczy also received many commissions from English merchants and soldiers too.

Berczy’s fame spread quickly in Montreal, and he received numerous portrait commissions, executed church decorations, and did some architectural work. Berczy was invited to Quebec City to paint what is perhaps his best-known portrait from this period, The Woolsey Family (1809)—a family portrait set in a finely decorated interior room; the father figure is placed at the centre, surrounded by his children, fine furniture, and loyal dog. The window on the left-hand side opens out onto a view of Quebec City, the gardens of the nuns of the Hotel-Dieu de Quebec, the St. Lawrence River and Orleans Island. As with many commissioned portraits, this painting communicates a great deal about the status and position of its sitters.

William Berczy met Joseph Brant, or Thayendanegea, the Loyalist Chief of the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawks) at what is now Niagara-on-the Lake, Ontario, in 1794. This portrait was executed after the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), one of the first truly global wars. Although Joseph Brant wasn’t heavily involved in the Seven Years’ War, he did work closely with the English militia, acting as an interpreter. Brant also aided missionaries in teaching Christianity to the Indigenous people of the area and helped translate religious materials into Kanyen’kehà (Mohawk). Berczy’s portrait shows Joseph Brant standing in a classically inspired pose with the head in a three-quarter profile. The outstretched arm evokes imperial authority, while the pleats in the brilliant red blanket echo the folds of a toga. Although the figure appears monumental—an effect emphasized by the low horizon line—each detail of the costume has been rendered with painstaking, almost documentary, precision. The toga aligns this work with classical Greek and Roman sculpture of emperors and other political leaders.

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.6

There is another aspect to this portrait worth considering. A year after the American Revolutionary War, in May 1784, Joseph Brant led the Kanyen’kehà Loyalists (those loyal to the British) and other Indigenous peoples to a large tract of land on the Grand River in southwest Ontario that was granted to them in compensation for their losses in the war. This tract was named Brant’s Ford (now Brantford, Ontario) after him. Because their tract of land was too small for hunting, Brant feared that Indigenous people would have to learn agriculture to survive. To provide them income, he hoped to lease or sell land to non-Indigenous people. A complicated controversy with the government arose over the nature of Indigenous land tenure, with Brant and other Mohawk leaders fighting for the right of their people to own the lands on which they lived. The government of Upper Canada refused to concede land title to the Mohawk in the Grand River Valley during Brant’s lifetime. For decades, from 1776 to his death in 1807, Brant fought in vain with the British and Upper Canada governments for the rights of the Mohawk people to obtain title to the lands of the Grand River Valley. Brant became known for his diplomatic work, especially as a leader of Indigenous tribes who fought for the right to remain on their ancestral lands. It is perhaps no wonder, then, that in Berczy’s portrait Joseph Brant is the focal point, personifying his status using European portraiture conventions for rulers and emperors, while the expansive background depicts the land awarded to the Six Nations on the Grand River.

Figure 3.6 Ruth Cuthand, Trading: Smallpox (2008). Acrylic paint, glass seed beads on beading medium mounted on suede board, 61 × 45.7 × 3.1 cm. MacKenzie Art Gallery.

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.7

Look closely at Trading: Smallpox by artist Ruth Cuthand and write a formal (visual) analysis of the artwork. Consider the materials used in conjunction with the subject matter. How might you begin to interpret this artwork? Refer back to the Slow Looking/Close Looking section in the Introduction module to review the steps.

In 2009, Cuthand created the series Trading, a collection of beaded and quilled artworks. Eleven of the works depict a different disease brought by Europeans to the Indigenous Americas; the twelfth depicts syphilis, the one novel disease that was brought back to Europe from Indigenous populations. The viruses represented in the Trading series are bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, diphtheria, influenza, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, syphilis, typhoid fever, whooping cough, and yellow fever. Each disease is visualized in its microscopic structure, as if in a petri dish. The name of each disease is stenciled in white acrylic paint against the matte black suede surface of the artwork underneath the circular image of the disease. The diseases brought by Europeans to the Americas are rendered using beads, while syphilis is displayed in quillwork, which consists of dyed porcupine quills sewn onto the backboard. As beads came to replace quills as a common currency for local trade they came to signify the unequal relations of Indigenous and settler systems of trade, where beads were exchanged for valuable furs. Their use is intended to signal both the exploitative practices of settler-colonialism more broadly and the new tools Indigenous peoples encountered because of exchange, such as iron and guns. The Trading series is a significant contribution to early 21st-century contemporary art through its evocative yet terrifying allegorical meaning.

Art historian Carmen Robertson describes Cuthand’s use of beadwork and its connection to land and territory in the following excerpts from her essay “Land and Beaded Identity: Shaping Art Histories of Indigenous Women of the Flatland”:

Indigenous beaders, too, hold a sensorial bond to place that translates through the process of making manifested in the beaded works. The movement of the needle and thread, creation of design, and choices of colour, demand keen performative attention, which both quiets and opens the mind. A key aspect of beading practices on the Plains references a generational sharing of technologies and knowledge. (15)

…With the arrival of Europeans to the Plains over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, cultural and artistic expressions changed and adapted new technologies to suit shifting identities. The quills, feathers, and natural pigments that adorned traditional garments were, for example, interspersed or replaced with glass beads, trade cloth, and new designs. Porcupine quillwork, a sacred art form connected to the ceremonies, societies, and protocols of the Plains peoples, served semiotically as a direct signifier of the land, with quills culled from porcupines and dyes derived from plants and other natural materials. Beads, then, operate as floating signifiers for the land, narrative traditions, and ceremony, but also for how colonial presence cross-pollinates to create meaning. Mohawk scholar Joel Monture puts it another way when he describes quillwork as the “grandmother of beadwork.” According to him, quillwork shaped beadwork in an evolutionary process, and the traditional Indigenous medium thus remains present.¹⁴ Beadwork, then, maintains an aesthetic connection to quillwork, even when contemporary issues and ideas complicate that meaning. (16)

Just as the bandolier bags invite close looking with their meticulous beadwork, Cuthand’s beaded representations of viruses and disease solicit the viewer’s engagement with their shiny, brightly coloured beaded surfaces. The diseases that Cuthand addresses were, and are, a by-product of trade and encounter, as with the glass beads.

In the next section, we will examine one of Canada’s best-known artists, Emily Carr, as well as contemporary artist Sonny Assu’s intervention into her artistic legacy. Finally, we will explore two contemporary artists, Brendan Tang and Brian Jungen, whose artworks address themes of identity, cultural value, and hyridization.

Legacies of colonial encounter

Settler artist Emily Carr is, like Paul Kane before her, a fascinating but deeply complicated case study in Canadian art history. Looking at her painting Totem Poles, Kitseukla, you might begin to wonder what this artist of British descent was doing, painting Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en totems in the village of Kitseukla. She straddled the ever-evolving colonial world of Canada, while simultaneously looking to Europe for the new and the modern. Her infatuation with Indigenous cultures was deeply romanticized, and she interpreted her encounters with, and depictions of, Indigenous culture as she saw fit.

Watch the Heritage Minute: Emily Carr by Historica Canada:

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.8

How does Historica Canada depict Carr’s encounter with Indigenous culture?

Emily Carr was born in Victoria, British Columbia, to British parents. Her mother and father died when she was a young woman. In 1890, to get away from Victoria, she convinced her guardian to let her study art at the California School of Design in San Francisco, when she was just 18. In late 1893, she returned to Victoria determined to be an artist and set up a studio in the family barn, where she proceeded to paint and offer children’s art classes. In 1899, at the age of 28, she saw an Indigenous village for the first time on a visit to the mission school at Ucluelet on the Pacific Coast of Vancouver Island (south of Tofino). Carr was intent on growing and developing as an artist and, having saved up enough money from her teaching, she left in 1899 for London, England to enrol in the Westminster School of Art. But her health soon began to suffer from the London air, and she decided to move to the artists’ colony at St. Ives in Cornwall for about six months in the early 1900s. In 1904, then 34 and with almost 15 years of art studies behind her, she decided to establish herself as an artist-teacher in Vancouver.

Carr’s early Vancouver work was nurtured in a slowly expanding art scene. She was also spurred on by a trip with her sister Alice to Alaska, where Carr chronicled their adventures extensively in notebooks and sketches, documenting everything they experienced, from extreme seasickness to visits to Sitka’s totem poles. The trip was the impetus for her next project which occupied the following five years of her life: to document Indigenous totem poles and village sites in BC.

In addition to her Alaska trip, Carr frequently visited the Indigenous reserves at Kitsilano and North Vancouver. Once back in Vancouver, she resolved––much as Paul Kane had done 60 years before––to paint a programmatic series that would record the villages and totems she saw for posterity, continuing a tradition of artists participating in the salvage paradigm. Over the next four summers, she visited many remote villages, painting hundreds of watercolours, but she was dissatisfied with the results. To gain more credibility as an artist and to strengthen her own skills, Carr left in 1910 for Paris, aged 39, hoping to acquire the pictorial language to express herself with force.

Carr stayed in Paris for 15 months and her time and training in France changed her work forever. While she didn’t take to big city life, in Paris she was exposed to the work of Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, and to the discourse of primitivism. Carr returned to Canada in the summer of 1912 and held an exhibition in her studio, bringing French avant-garde artistic traditions to Vancouver.

Art historian Gerta Moray defines primitivism as “the belief that the art of supposedly primitive societies had an expressive truth that transcended naturalistic representation” (Moray 2010, 60). Carr’s interest in primitivism fostered her conviction that the Indigenous visual culture she had seen on her earlier travels (the villages, totems, artefacts, and carvings) “should be recorded and preserved as well as emulated” (Moray 2020, 61). Overjoyed and bolstered by her recent success, Carr spent the summer of 1912 working first in Kwakwakaʼwakw villages on the east coast of Vancouver Island, then among the Gitxsan of the Upper Skeena River, and finally with the Haida of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands). In the autumn of that year she painted pictures employing the intense colour and broad, expressive brushwork she had learned in France. Totem Poles, Kitseukla documents a Gitxsan village scene with intact poles situated in close proximity to a series of houses and a few figures seen in the background, in contrast to Tanoo, Q.C.I., which shows no inhabitants, an historically accurate depiction reflecting the aftermath of the smallpox epidemics that devastated all except two Haida villages.

Carr exhibited these village scenes and other works from this period in her studio in April 1913, the largest one-person show ever held in BC. Sadly, Vancouver viewers seem to have found these paintings difficult to accept. The paintings challenged spectators much more than her French paintings had. Carr sold no pictures from the exhibition and attendance fell off at the painting classes she depended upon for her living. She retreated to Victoria and built a four-suite apartment in the hope of making a living as a landlord to support her art. Life became quite difficult, and Carr, at the age of 42, all but ceased any serious painting. Her reputation as an outsider grew.

Another reason for Carr falling out of favour with gallery-goers was her fervent, almost militant, modernism and her championing of Indigenous traditions. She had, as we might expect, internalized a colonialist view of Indigenous culture. She wrote, for example: “I glory in our wonderful west and I hope to leave behind me some of the relics of its first primitive greatness. These things should be to us Canadians what the ancient Britons’ relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness and I would gather my collection together before they are forever past” (Shadbolt 1979, 38). Carr may have had great respect for Indigenous culture, and her desire to salvage or preserve what she saw in BC was perhaps connected to values she was witness to in Indigenous cultures, such as pride in ancestry represented through totem animals, the power of First Nations women, and the terror inspired by nature and the elements. However, we cannot discount Carr’s privileged position as a white colonial settler and her appropriation of Indigenous material culture in her choice of subject matter.

In the 1920s she came into contact with members of the Group of Seven after being invited by the National Gallery of Canada to participate in the 1927 Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art, Native and Modern. This was another turning point for Carr as it gave her work greater exposure out east for audiences in Ontario.

Later in her career, Carr devoted her attention more to ecological themes, painting numerous images of clear-cut logging and the effects of deforestation. In Odds and Ends the cleared land and tree stumps shift the focus from the majestic forestscapes that lured European and American tourists to the West Coast, to reveal instead the impact of deforestation. Her concern with the effects of industry and its environmental impact, developments that were evident in outlying regions near the BC capital, paralleled her concern with encroachments on the lives of Indigenous people. Large-scale industrial logging had begun in British Columbia in the 1860s, and its influence was visible. We see at this time Carr’s anxiety about this industry as her choice of subject becomes the threatened landscape. At 64, Carr had begun to feel the joy of public recognition. She had great success in her late career, selling many paintings in exhibitions in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. She passed away in 1945, by which time her importance in Canadian art was unquestionable.

Emily Carr’s legacy has been examined and critiqued in more recent years by many scholars and art historians, who have grappled with the artist’s appropriation of and relationship to Indigenous culture. The following excerpt from Marcia Crosby’s essay, “The Construction of the Imaginary Indian,” is written from an Indigenous perspective and discusses the salvage paradigm and the ways that artists like Paul Kane and Emily Carr participated in it.

An interesting aspect of the salvage paradigm is that it may occur at many historical points. James Clifford describes the conditions under which “saving” an “othered” culture takes place: “a relatively recent period of authenticity is repeatedly followed by a deluge of corruption, transformation, modernization. . . but not so distant or eroded so as to make collection or salvage impossible.” Some sixty years after Paul Kane had recorded the remaining images of so-called authentic Indian life, Emily Carr made up her mind to record for posterity the totem poles of the Northwest Coast in “their own original” village settings before they became a thing of the past. Like Paul Kane, Carr claimed her paintings were “authentic.” There is a double edge to her serious endeavour to record for posterity the remnant of a dying people: Carr paid a tribute to the Indians she “loved,” but who were they? Were they the real or authentic Indians who only existed in the past, or the Indians in the nostalgic, textual remembrances she created in her later years? They were not the native people who took her to the abandoned villages on “a gas boat” rather than a canoe. My point is that the “produced authenticity” or stereotype that Clifford refers to is invisible in Carr’s work, and therein lies the danger. It could be argued that her paintings were authentic or real in the sense that they were ethnographic depictions of actual abandoned villages and rotting poles. However, the paintings of the last poles intimate that the authentic Indians who made them existed only in the past, and that all the changes that occurred afterwards provide evidence of racial contamination, and cultural and moral deterioration. These works also imply that native culture is a quantifiable thing, which may be measured in degrees of “Indianness” against defined forms of authenticity, only located in the past. Emily Carr loved the same Indians Victorian society rejected, and whether they were embraced or rejected does not change the fact that they were Imaginary Indians.

Images of abandoned villages, such as Tanoo, with the remaining poles leaning over, rotting in neglect and deterioration, call up images of a not-too-distant culture removed from the present. The remaining fragments of Northwest Coast native culture are to be recorded for the historical interests of British Columbia and Canada.

Obviously, material culture does not grow or exist in a forest by itself. The poles Carr painted were created by and belong to the First Nations peoples of the Northwest Coast. Carr’s literary description, in her mission statement, of the poles as relics to record (to “save” as traces of “the West’s primitive greatness”) locates her work within the salvage paradigm. She describes the poles as belonging to a geographical space, a landscape devoid of its original owners. Her association of the material culture of the Northwest Coast native people with the “primitive greatness of the West” was naturally facilitated by the already entrenched construction of the Indian as nature. Carr invests the “relics” of her country, Canada, with a meaning that has to do with her national identity, not the national identity of the people who own the poles. The issue here is that the induction of First Nations peoples’ history and heritage into institutions as a lost Canadian heritage should be considered within the context of the colonization of aboriginal land. At this time, when the struggles of First Nations people for aboriginal rights and self-identity are being widely publicized, it is inappropriate, I think, for an art historian to describe Carr’s remarks as a “statement of high moral purpose.” However, commonly held notions not only of Imaginary Indians, but of Canada’s mythical icons––or sacred cows––die hard.

Crosby summarizes her concerns with Carr:

I do not believe that Carr could have possibly had “a profound understanding” of the many nations of native people who inhabited the Northwest Coast during her time. They were, and still are: Nisga’a, Gitksan, Tsimshian, Haisia, Haida, Nuu’chah’nulth, Kwagiulth, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Songish, Cowichan, Nanaimo/Chemainus, Comox, Sechelt, Squamish, and Sto:lo. (this list does not include the southern-, central- or northern-interior nations.) If she did forge a deep bond with an imaginary, homogeneous heritage, it was with something that acted as a container for her Eurocentric beliefs, her search for a Canadian identity and her artistic intentions (1991).

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.9

What is your reaction to Marcia Crosby’s analysis and critique of Emily Carr? Consider your own perspective on Emily Carr and her artwork. How might we both appreciate her artworks, while at the same time remain aware of the role she played in colonization and in colonial attitudes toward Indigenous peoples?

It is hard to look past the bold, bright and graphic “tag” that contemporary Liǥwildax̱w/ Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Sonny Assu, foregrounds in his artwork, What a Great Spot for a Walmart!, to what lies beneath, but keep looking and you will see a historical work by Emily Carr from 1912. This 2014 “digital intervention” re-appropriates a historic painting by Carr, who, in turn, appropriated totem poles and Indigenous villages. “I think a lot of people assume that she was documenting a dying race,” Assu says. “But indigenous [sic] peoples are still here. We were brought to the brink of extinction. And now we’re fighting back” (Crawford 2016). Much of Assu’s work addresses issues such as Indigenous rights, consumerism, branding, new technologies, and the ways in which the past has come to inform contemporary ideas and identities.

Watch Sonny Assu discuss his exhibition “A Radical Mixing” at Canada Gallery, Trafalgar Square in London, England here:

In an ongoing series of works entitled Interventions on the Imaginary, Sonny Assu overlays digital “tags” onto historical paintings by settler artists like Paul Kane, Edwin Holgate, and Emily Carr. His bright, often neon-hued graffiti of ovoids and formline shapes hover like spacecraft over the appropriated and often iconic, historical images he has selected. Historical paintings by Emily Carr, for example, are suddenly marked by both a spectre and a contemporary presence of Indigenous peoples. His gesture is a form of resistance and emphasizes Crosby’s notion of “the Imaginary Indian,” a Western notion that has positioned Indigenous peoples as inferior and as a vanishing race. This notion has plagued popular representations of Canada, such as those made famous by the Group of Seven and Emily Carr, and has worked to picture the land as empty and unoccupied, as terra nullius. Through Assu’s appropriation of these art historical images and their juxtaposition with graphic Indigenous formline and satirical titling, Interventions on the Imaginary interrupts and ultimately unsettles (art) histories of colonization.

One of the most recognizable visual styles of Northwest Coast Indigenous art is formline, which contains ovoid, U and S forms, and features continuous curvilinear lines that outline figures, fill shapes and abstract designs. Assu’s use of formline within the series contrasts with the genres of Western art history painting that he appropriates. Assu makes visible an important practice of Indigenous artistic innovation and cultural resilience, prioritizing it over Western narratives of settlement and “progress” depicted in the appropriated paintings’ backgrounds. His use of bold colours makes the ovoids all the more visible, the graphic neon colour pairings interrupting and unsettling the landscapes they hover over. For instance, in Re-invaders (2014), which appropriates Carr’s painting Church at Yuquot (formerly Indian Church), Assu inserts neon pink and purple ovoid and U-shapes over the church, suspended like space invaders as the title suggests. The positioning of the formline hovering over the historic white building is significant. Like a graffiti tag on a wall, the formline attaches a signature of Indigenous survivance on the landscape, or what Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor explains as a radically active presence that moves beyond mere survival but connects to issues of sovereignty (2009).

In What a Great Spot for a Walmart! Assu appropriates Emily Carr’s Graveyard Entrance, Campbell River because it specifically depicts the graveyard in his grandmother’s village. Assu writes, “Today the geographical landscape of the graveyard entrance is dramatically different. However, a replica of the Thunderbird totem stands in a nearby band-owned commercial development. Just beyond the tree line in the background of this painting, a modern-day Walmart can be found. Although the store is not located in a culturally sensitive area, with this intervention I’m questioning the desire of First Nations to adopt colonial ways of consumerism, commerce and resource extraction as a means to provide a mode of income for their Nation(s). While I understand the need for and support a Nation’s mandate to build infrastructure to provide for the betterment of their people, I question what we might pave over in order to provide for our own” (Assu). Assu suggests that land continues to be colonized now, through processes of capitalism.

Curator Candice Hopkins locates Assu’s interventions within the trajectory of Canadian art history:

This repudiation of dominance, the resistance to narratives of nihilism, carries forward into Assu’s recent series, Interventions on the Imaginary, which began as a playful intrusion of one culture’s aesthetic practice into another. Brightly coloured ovoids descend, alien-like, into the picture plane of well-known paintings of the Northwest Coast by Emily Carr, Paul Kane and others. These paintings are almost entirely devoid of Indigenous people. Scholars such as Marcia Crosby have pointed out that what stands in for the absence of people, particularly in the work of Emily Carr, are signs of their demise: gravestones, memorial poles, and abandoned houses. The tongue-in-cheek titles for work in the Interventions series, including Spaced Invaders (2014) and What a Great Spot for Walmart! (2014), potentially obscure the deeper implications of what is initially proposed by these images––namely, making the Northwest Coast formlines appear strange and the paintings, done by the newcomers to the land, appear natural.

Growing up in the 1980s, Assu has stated interest in remix culture. This is found in the bold colour choices of his paintings that are more akin to the urban vernacular of the street than to the more muted palette of his ancestors. This isn’t a new tactic. The American media scholar Henry Jenkins argues that “the story of American arts in the 19th century might be told in terms of the mixing, matching, and merging of folk traditions taken from various Indigenous and immigrant populations.” This is also apparent in the paintings that Assu chooses as his source material. For Emily Carr, it wasn’t enough to represent the landscapes and villages of Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nult, Tsmishian, and Haida peoples; in her own form of cultural cannibalism, she quite literally became the other. For a time, she took on an Indigenous name, Klee Wyck. She also created works that took on the aesthetics broadly associated with Northwest Coast art, including ceramic bowls decorated with ravens, serpents, and turtles in a rather unsophisticated formline.

This being said, Interventions on the Imaginary challenges what is “natural” and what is a construct. While much of the early paintings of the Northwest Coast, including those by Carr, are described as landscapes, Marcia Crosby notes that “[Carr’s] association of the material culture of the Northwest Coast native people with the ‘primitive greatness of the West’ was naturally facilitated by the already entrenched construction of the Indian as nature.” Thus, the picture planes that Assu’s ovoids descend upon and over, like spaceships from another planet, are anything but natural. They are images inscribed with power and the entanglement of colonial relations. In some, like the rather elaborately titled Yeah…shit’s about to go sideways. I’ll take you to Amerind. You’ll like it, looks like home (2016), an ovoid hovers over a group of people seated in a circle in front of a big house, as though their own cultural forms have come back from the future to rescue them from Western painterly oblivion (Hopkins 2018, 25-27).

VIEW SELECTED WORKS FROM BRENDAN TANG’S MANGA ORMOLU HERE

Figure 3.9 Brendan Tang, Manga Ormolu 4.0 (2012) Ceramic and mixed media, 24 × 53 × 9 23 cm.

Themes of encounter and cross-pollination are central to the work of Brendan Lee Satish Tang. Tang’s ceramic works explore “issues of identity and the hybridization of our material and non-material culture while simultaneously expressing a love of both futuristic technologies and ancient traditions. Although he is primarily known for his ceramic work, Tang continues to produce and exhibit work in a wide variety of mixed and multiple mediums” (Tang).

Tang’s own history is as hybrid as his objects. He was born in Dublin, Ireland to Trinidadian parents who are of Chinese and East Indian descent. Manga Ormolu 4.0 is part of a larger series of ceramics in which ancient Chinese porcelain vases and objects battle futuristic robotic parts. Art historian Anne Dymond describes Tang’s work:

Like Rococo ormolu—French gilded luxury fittings applied in the 18th century to imported Ming and Qing dynasty vases (among other objects) to make them more appealing to European aristocracy—Tang’s vessels are the product of long and ongoing cultural interplay. Each piece begins with what looks like a traditional hand-painted Chinese vase, mostly blue and white, complete with a delicate craquelure that suggests authenticity. Yet where Europeans framed the East by adding golden filigree, Tang anachronistically adds cyber-pop ceramic armatures, airbrushed to smooth perfection, which are simultaneously fun and menacing.

Tang relates the robotic references to Japanese comics and anime, which, like ormolu, are culturally complex. They evolved out of a combination of Western and Japanese traditions, became incredibly popular in Japan and are now, in some sense, global. Tang’s work adds nuance to the seeming permanence of cultural archetypes, revealing the malleability of such categories in contemporary culture as well as their staying power. While manga is part of global pop culture, it still stubbornly reads as Japanese. Similarly, while the blue-and-white ceramics have been copied in Delftware and the Ming dynasty’s blue glaze may have been imported from the West, they persist in signifying the Chinese (Dymond 2022).

Watch Anatomy of an Object: Manga Ormou, which takes a close look at Tang’s Manga Ormolu series, here:

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.10

The previous video provides a definition for ormolu. What is it? How does it relate to Tang’s work? Consider what he is referencing in his sculptural artworks. How do you interpret this densely layered work? How does it connect to others you have seen in this module?

Brian Jungen is another artist whose multimedia sculptural artworks reveal an interest in hybrid combinations and eclectic mixes of materials from different cultures. Many of Jungen’s artworks are made from cut-up, dismantled, and reconstructed objects found in our everyday lives: Nike basketball shoes, golf bags, plastic chairs, recycling bins, and gasoline jugs, to name just a few. Cutting up, disassembling, and recombining materials works to create new meaning out of often ordinary, everyday objects.

Jungen’s Prototypes for a New Understanding (1998-2005) is a series of twenty-three masks created by taking apart Nike Air Jordan sneakers and putting them back together with human hair to produce soft sculptures that resemble Indigenous Northwest Coast masks. Curator Kitty Scott writes,

These forms have been understood as markers of cultural hybridity and critiques of consumerism and tidy ethnographic orders, as well as of the systems of museological display. In art-historical terms, these works may be broadly aligned with the neo-conceptual turn of the previous decade. More specifically, Jungen’s strategy of working with objects from the dominant culture in order to re-signify those materials might be compared with the approaches of African American artists such as David Hammons, Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker, or Fred Wilson. . . . Jungen would similarly turn toward popular culture and its representations of Indigeneity. The city of Vancouver had long incorporated generic motifs such as riffs on flat Haida formline designs, abstract renderings of thunderbirds and distinctive geometric forms into its civic identity, and Jungen was interested in how people perceived them without fully understanding what they were. At the same time Jungen was becoming interested in Air Jordans “as a collectible commodity, just like Native art” (Jungen). As he has stated, the Prototypes series is “about my experience of being First Nations and trying to figure out what that means at this time” (Enright) (Scott 2019, 15).

Scott alludes to Jungen’s Prototypes use of the black, red, and white colours of the classic Nike Air Jordan sneaker to evoke the colours of Haida masks and carvings, which have become ubiquitous on the West Coast, and have come to stand in for much Indigenous art and visual culture in Canada. Prototype for New Understanding #16 (2004) considers the immense cultural currency and rarity of sports paraphernalia (Air Jordans were costly in the 1980s and now command outrageous sums on eBay), and, by placing them in a gallery or museum, Jungen asks viewers to consider how we assign cultural value.

Basketball is as popular on First Nations reserves as anywhere, and the aspiration to the high style and high-level performance associated with Nike Air Jordans––a fashion made popular by 1980s rappers as well as aspiring athletes––is central to Jungen’s commentary. Deconstructing these status objects calls their associated symbolism into question; it also deconstructs their cultural capital. Jungen performs a powerful gesture, a violent act that dismantles the high-priced shoe by literally ripping it apart, all the while calling into question the stereotypical representations of Indigenous cultures. The colours and shapes of the sneakers lend themselves particularly well to Northwest Coast imagery, the swoosh operating like the classic U-form and ovoid shapes associated with Northwest Coast formline design. The Prototypes are a critical commentary on the tourist trade in souvenir Indigenous masks, often made for a market economy, and clashes them with the over-priced, globally sought-after commodity of the Air Jordan shoe. These hybrid sculptures make connections between more “traditional” Northwest visual culture and popular sportswear fashion, calling into question the ways that we arbitrarily assign value to objects that have no direct connection to their original use, and transform them into fetish objects.

LEARNING JOURNAL 3.11

Find and do some research about one other artwork by Sonny Assu, Brendan Tang, or Brian Jungen that addresses the idea of encounter. Write a 200-word paragraph describing the work’s form, subject matter, context, and meaning. How does the artwork that you have chosen address themes of encounter, exchange, or hybridity?

OBJECT STORIES

- Alison Ariss on Gina Grant, Helen Calbreath, Krista Point, Debra Sparrow and Robyn Sparrow, Out of the Silence (1997)

- Jennifer Burgess on the Inuvik Parka (1960-80)

- Emma Hassencahl-Perley on O’Halloran’s Outfit (c. 1841)

- Michael Rattray on Ruth Cuthand, Covid-19 Mask No. 6 (2020)

- Linda Sioui and Annette de Stecher on the Elgin Trays (1847-54)

References

Assu, Sonny. n.d. “Interventions On The Imaginary.” Sonny Assu. Accessed February 6, 2022. https://www.sonnyassu.com/pages/interventions-on-the-imaginary.

Clifford, James. 1987. “Of Other Peoples: Beyond the Salvage Paradigm.” In Discussions in Contemporary Culture, edited by Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay Press.

Crawford, Amy. 2016. “Sonny Assu Uses Graffiti to Reassert Native Culture.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/sonny-assu-graffiti-native-culture-180961143/.

Crosby, Marcia. 1991. “The Construction of the Imaginary Indian.” In Vancouver Anthology: The Institutional Politics of Art, edited by Stan Douglas, 267-94. Vancouver: Talon Books.

Deer, Ka’nhehsí:io. 2019 “Odawa Anishinaabe Artist Swaps Glass Beads for Resistors and Capacitors.” CBC News, November 17, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/electronic-bandolier-bags-barry-ace-1.5361435.

Eaton, Dianne. 1996. Paul Kane’s Great Nor-West. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Enright, Robert. 2011. “The Tortoise and the Air: An Interview with Brian Jungen.” Border Crossings 30, no. 2 (May): 31.

Gehmacher, Arlene. 2014. Paul Kane: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/paul-kane/.

Jungen, Brian. 2019. In conversation with Kitty Scott, October 23, 2017. Cited in Brian Jungen: Friendship Centre, edited by Kitty Scott. Munich: Prestel Verlag.

Monture, Joel. 1993. The Complete Guide to Traditional Native American Beadwork. New York: Wiley Publishing.

Moray, Gerta. 2010. “Emily Carr: Modernism, Cultural Identity and Ethnocultural Art History.” In The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century, edited by Brian Foss, Sandra Paikowsky, and Anne Whitelaw. Don Mills, ON: University of Oxford Press.

Olsen, Sylvia. 2010. Working with Wool: A Coast Salish Legacy and the Cowichan Sweater. Winlaw, BC: Sono Nis Press.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession (1991): 33-40.

“The Provincial Exhibition.” 1852. Anglo-American Magazine (Toronto) 1, no. 4 (October): 371-72.

Robertson, Carmen. 2017. “Land and Beaded Identity: Shaping Art Histories of Indigenous Women of the Flatland.” RACAR 42 (2): 13–29.

Saul, John Ralston. 2002. “His Excellency John Ralston Saul Introduces Georges Erasmus, The 3rd LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecturer.” The Globe and Mail, March 13, 2002. https://archive.gg.ca/media/doc.asp?lang=e&DocID=4543.

Scott, Kitty, ed. 2019. Brian Jungen: Friendship Centre. Munich: Prestel Verlag.

Scott, Kitty. “Courtside.” In Brian Jungen: Friendship Centre, edited by Kitty Scott, 14-23. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario; DelMonico Books; Prestel.

Shadbolt, Doris. 1979. The Art of Emily Carr. Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre.

Tang, Brendan. n.d. “About.” Brendan Lee Satish Tang. Accessed February 5, 2022, http://www.brendantang.com/about.

Vizenor, Gerald. 2009. Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

A term coined by Mary Louise Pratt, a contact zone is the often tense meeting point between societies and cultures with a current and/or historic imbalance of social, political, or cultural power.

The change in culture(s) resulting from contact with another, particularly as a result of colonization in which a colonized culture meets with and transforms aspects of the colonizing culture.