COLLECTIVITY

VIEW THE ACHIEVING A DREAM TAPESTRY HERE

Figure 9.1 Oolassie Akulukjuk, Dinah Andersen, Kathy Battye, Anna Etuangat, Leesee Kakee, Kawtysie Kakee, Sammy Kudluk, Louie Nigiyok, Mabel Nigiyok and Andrew Qappik (designer), with support from David Cochrane and Deborah Hickman, Achieving a Dream, 2009. Wool and cotton, 172.7 x 301 cm. Photograph: David Kilabuk, © The Artists.

A ski jumper sails through the air. A determined speed skater cuts a narrow path. And a hockey player raises his glove, signalling to an imagined arena. Among them are Inuit playing traditional games of the North. All of this takes place against a surreal backdrop, a landscape that is at once no place and many in the land now called Canada. This monumental tapestry, Achieving a Dream (2009), commissioned for the 2010 Olympic Games in Vancouver, not only brings together various sporting traditions and multiple geographies, it is also the collaborative work of many artists, including those who work with pencil and with wool.

The Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio, now part of the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts (which also includes a print shop) in Panniqtuuq, Nunavut, has been producing tapestries since the early 1970s. At minimum a collaboration between a local artist, who supplies the design, and a local weaver, who chooses materials and colours and translates the cartoon into wool, the tapestries have become a site for experimentation, storytelling, and community building.

Weaving is common among many North American Indigenous populations, including the Tsimshian of the Northwest Coast, who produce finger-woven blankets of cedar bark and mountain goat wool, and the Navajo of the American Southwest, who translate worldviews with the wool of the Navajo-Churro sheep, an animal that has been central to Navajo culture since the Spanish conquests of the 16th century. However, the presence of weaving among Inuit is a little different, as there is no natural source of spun fibre in the northernmost reaches of Canada. Instead, weaving came to Panniqtuuq through an employment scheme, part of the efforts of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs to establish arts and crafts programs in the Arctic. Though this program coincided with a revival of the textile arts which swept Canada in the mid-20th century, it was regarded more prominently by Canadian government officials as a means of supplementing, or even replacing, the livelihood Inuit made on the land, and an incentive for Inuit to remain in settled communities rather than seasonal camps.

At the same time, weaving drew upon the skills and strengths of the women residing in Panniqtuuq. Experts at fashioning caribou and seal skins into amautiit (women’s parkas) and kamiit (boots), in a climate where the fault in a seam could mean the difference between life and death, women were able to transfer the precision learned through sewing and working skins to weaving. According to early accounts from the weaving studio, the first women who participated in the training program quickly learned how to operate the European-style floor and tapestry looms and to work with wool, often imported from Iceland (Goldfarb 2020). But what emerged from this process was a fusion of European tapestry techniques and Inuit sensibilities. Unlike the tapestries produced at the major French workshops of Gobelins and Aubusson, which have a distinct front and back, the two sides of the tapestries made at the Pangnirtung Studio are nearly indistinguishable. This neat finishing harks back to Inuit women’s skills in other textile mediums.

Achieving a Dream is a composite image, and while the addition of athletes suits the subject of the commission, many of the other elements depicted are consistent with the broader output of the studio. Pangnirtung’s tapestries are varied, but the artists often return to significant subjects: the land, mythical beings or animals—here signified by their tracks in the snow—and scenes of traditional Inuit life. Some have suggested that the designers return to these ideas again and again because they are popular with those who purchase Pangnirtung’s tapestries. However, as Maria von Finckenstein has argued, it is reductive to reduce the richness of the studio’s output to market concerns. The tapestries also offer Inuit a space to document their own narratives and history: “The motivation behind the scenes from the past is, I believe, a deeply felt need on the part of the artist-weavers to hold on to their cultural roots and to express them in their images. Says Leesee Kakee, a long-time member of the studio, ‘Some people might think these are just wall hangings, but they are a part of us, our ancestors, our lives’” (von Finckenstein 2002, 7).

The communal aspect of storytelling evident in the tapestries’ imagery is also fundamental to the structure of the studio itself. For Achieving a Dream, for instance, Dinah Andersen, Sammy J. Kudluk, Mabel Nigiyok, and Louie Nigiyok supplied the individual design elements, which were assembled by Andrew Qappik, and weavers Oolassie Akulukjuk, Kawtysie Kakee, Leesee Kakee, Anna Etuangat, and Kathy Battye spent 2,030 hours translating the image to wool, working in consultation with Uqqurmiut’s artistic advisor, Deborah Hickman, and Scottish weaver David Cochrane, who advised on some of the techniques needed for creating the large-scale project. While the Olympic commission is one of the largest works the studio has completed, this collaborative form of working is also reflected at the smaller scale. As Hickman notes, dialogue and conversation are central to the process of selecting a drawing from those sourced from the community for weaving: “The images provided by the artists provoke discussions of the traditional Inuit way of life and the recounting of shared family stories. Personal interest in the subject or style of the drawing is a major consideration when the weaver is making her selection. She must also consider the suitability of the drawing to the weaving process. Together the tapestry weavers, studio manager, and arts adviser discuss the selected drawings before a final selection is made” (Hickman 2022, 47). This consultative process not only determines the final look of the work, it recalls methods of the historical tapestry workshops at Gobelins and Aubusson, upon which the Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio is loosely based. Here again, the women of Panniqtuuq have adapted this method of working to their own needs and desires. Of his experience of working with the Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio, David Cochrane notes how the studio was infused with laughter: “Their hands were always in motion, be it weaving or winding and crocheting during tea breaks—productive and happy” (Cochrane qtd. in Inuit Art Quarterly 2022).

The products of many hands, and of skills and stories passed through generations, the tapestries produced by the Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio are truly collaborative works, and offer one example of how collective labour has shaped art in Canada. The history of art has long been centred on the mythos of the lone male artist-genius, thus neglecting the collectives and collaborative labour that is also part of art history. This module seeks to reframe some of the more celebrated Canadian artworks by thinking about what might be gained when artists work together.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.1

As the Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio weaving Achieving a Dream reveals, working collaboratively can yield some truly spectacular results. This module seeks to reframe some of the more celebrated Canadian artworks by thinking about what might be gained when artists work together and to examine where, when, and why artists have formed organizations, collective and collaborations. In a few sentences, consider why you think artists might choose to work together or form artistic organizations. What benefits might come from such alliances?

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- explain the major art associations and artistic groups that have shaped Canadian art

- describe the establishment of various Canadian artistic groups

- analyze the connection between particular visual media, politics, and nationalism in Canada

- evaluate the development of abstract art and its political context in Canada.

It should take you:

Achieving a Dream Text 12 min, Video 4 min

Developing modern art in Canada, together Text 58 min, Video 59 min

Imagined communities Text 16 min, Video 10 min

The rise of abstraction and the Automatistes Text 44 min, Video 16 min

Skawennati TimeTravellerTM Text 8 min, Video 6 min

Learning journals 8 x 20 = 160 min

Total: Approximately 6 h 35 min

Key works:

- Fig. 9.1 Oolassie Akulukjuk, Dinah Andersen, Kathy Battye, Anna Etuangat, Leesee Kakee, Kawtysie Kakee, Sammy Kudluk, Louie Nigiyok, Mabel Nigiyok and Andrew Qappik (designer), with support from David Cochrane and Deborah Hickman, Achieving a Dream (2009)

- Fig. 9.2 John A. Fraser, A Shot in the Dawn, Lake Scugog (1873)

- Fig. 9.3 Ontario Society Members at the Opening of the Art Museum of Toronto (1918)

- Fig. 9.4 George A. Reid, Mortgaging the Homestead (1890)

- Fig. 9.5 Paul Peel, After the Bath (1890)

- Fig. 9.6 J.E.H. MacDonald, The Arts and Letters Club (n.d.)

- Fig. 9.7 J.E.H. MacDonald, Goat Range Rocky Mountains (1932)

- Fig. 9.8 A.C. Leighton, Mount Skoki (1935)

- Fig. 9.9 Edwin Holgate, Edwin A. Sherrard at the Violin (1934)

- Fig. 9.10 Lilias Torrance Newton, Self-portrait (c. 1929)

- Fig. 9.11 Pegi Nicol MacLeod, School in a Garden (c. 1934)

- National Film Board of Canada, “Headline Hunters” (1945)

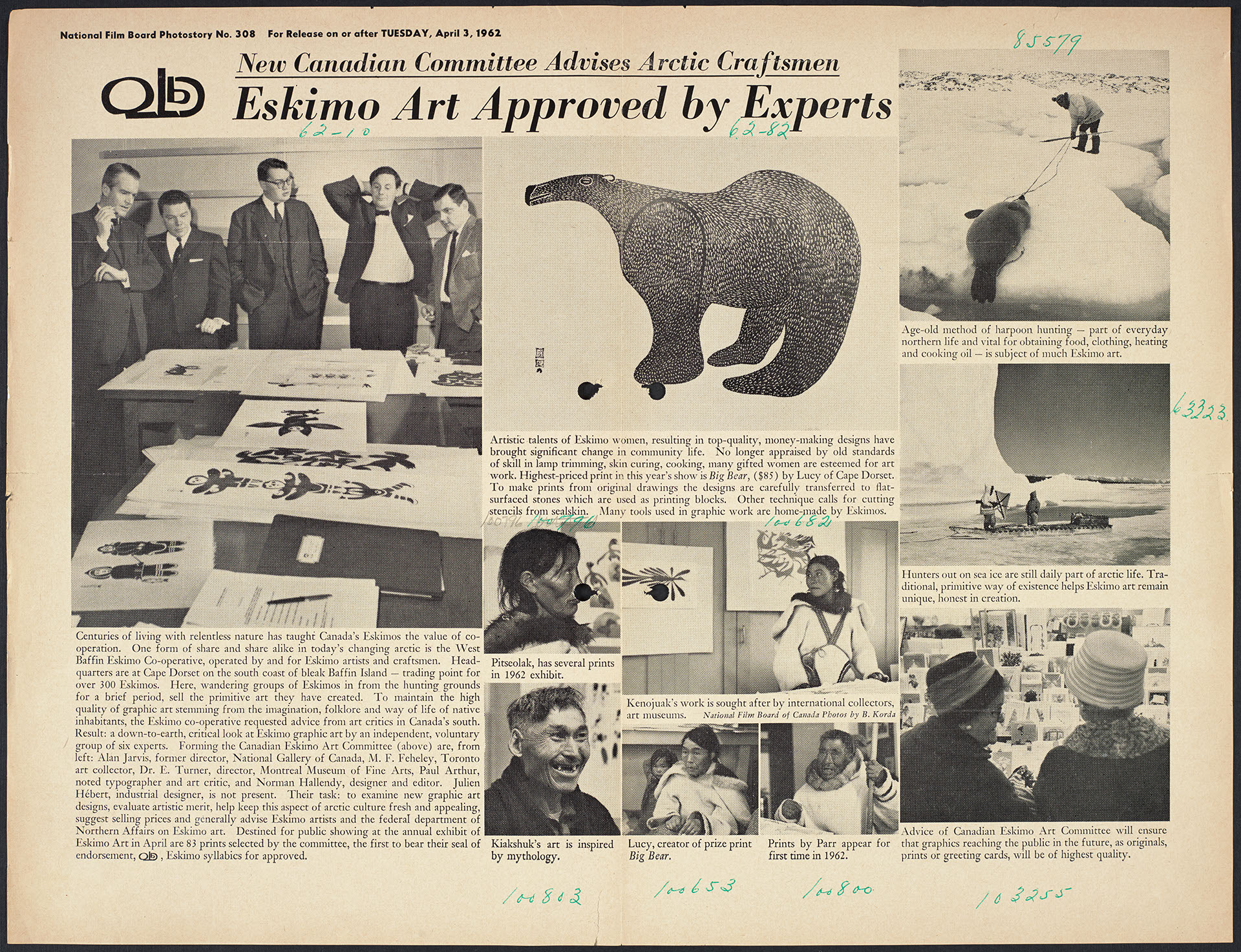

- Fig. 9.12 National Film Board, “Photostory #308: New Canadian Committee Advises Arctic Craftsmen: Eskimo Art Approved by Experts” (1962)

- Fig. 9.13 Paul-Émile Borduas, Abstraction verte (1941)

- Fig. 9.14 Paul-Émile Borduas, Sous le vent de l’île ou 1.47 (1947)

- Fig. 9.15 Refus global (cover) (1948)

- Fig. 9.16 Jean Paul Riopelle, Pavane (1954)

- Skawennati Time Traveller (2008-2013)

Developing modern art in Canada, together

Art history is traditionally presented as the individual (male genius)’s struggle for self-expression, but artistic collaboration and collectivity have also been central in art. This is particularly the case with the advent of modern art in the 19th century. Because art movements like Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism (to name but a few), were radical breaks from traditional academic artistic convention, it was particularly useful for modern artists to gather together, support one another, and help each other find exhibition venues to show their works to the public. Artist organizations and collectives worked together towards similar goals, united by political, economic, professional, or historical circumstances.

Artist organizations and societies were one of the earliest forms of art establishments in Canada. Beginning in the 19th century, groups of visual artists began forming often short-lived societies that have had a major influence on both professional and amateur artists. These organizations sit somewhere between the individual artist and the formal art institution. Art history is often taught as an ongoing series or chronology of artists. Examined in this way, artists and their work appear as unique and isolated. Focus is placed on the process, method, and output of the individual. Recently, re-examinations of the field of art history have called into question institutions—museums, galleries, schools—as determining which artists and works become a part of the art historical canon and are, in this regard, deeply problematic for their exclusionary biases. This is particularly evident in the nation-building exercise of Canadian identity, in which major institutions such as the National Gallery of Canada were mandated with exhibitions of artists that reflected particular conceptions of Canadianness.

Both the artist and the institution, however, sit at extremes. In the middle ground is the coming together of artists who want a community of shared outlooks and visual explorations, but not the imposition of stifling institutional mandates. In this middle ground, artists can take risks while still being supported by a community of peers. Sometimes these risks are played out in paint on a canvas, and sometimes these risks come in the form of political activism.

Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, collectives, associations, societies, and other groups were formed around unifying ideas presented through exhibitions, pamphlets, and manifestos. These groups were often deeply concerned with considerations of identity. In some instances, the coming together of artists would crystalize into a much more rigid and formalized institution. For example, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), established in 1880, was given its title by the British Queen Victoria and followed European traditions of selective membership to an art academy and calculated exhibitions of work. The RCA mirrored European models of art education and display, but had three key goals that were specifically Canadian outlined in its organizational constitution: to hold exhibitions in principal cities across what was then known as the Dominion of Canada; to establish a school of art and design; and to establish a national gallery at the seat of government. The RCA was the foundation for the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa as it exists today.

Founded in 1867, the same year as the Canadian Confederation, the Society of Canadian Artists (CSA) came together and pushed against the RCA’s commitment to the European organizational structures of the art academy. Instead, the CSA aspired to sell and exhibit work by Canadian artists in a market that still preferred European art. It was one of the first attempts to establish and support a local Canadian art market. Members of this group include painters Allen Edson, Adophe Vogt, C.J. Way, Henry Sandham, and John Fraser. Fraser played an important role in establishing the Society of Canadian Artists, though the organization quickly dwindled after he left in the same year it was founded. While there was no unifying visual style amongst its members, many of the artists emphasized qualities of ruggedness and demonstrated an interest in the qualities of light, as seen in Fraser’s A Shot in the Dawn, Lake Scugog (1873). These qualities continued to predominate in landscapes painted by the CSA throughout the 20th century.

Fraser went on to serve as the first Vice-President of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA), founded in 1872 in Toronto. Like the RCA, it had a mandate to foster original art and hold an annual exhibition. Unlike the RCA, it focused on supporting the work and ideas of Ontario-based artists. Part of its constitution was the establishment in Toronto of a permanent public art gallery, which it did in 1900 under the name Art Museum of Toronto, now the Art Gallery of Ontario. The organization was also concerned about the lack of art education in Ontario. By 1912, the OSA was granted a charter by the provincial government to establish an art college. George Reid was appointed the Ontario College of Art’s first principal.

Artist organizations such as the RCA and OSA quickly formalized institutions, and also fostered a flourishing of Canadian artistic production through stability, structure, and newly generated interest in art produced in Canada. Within this climate, artists who were members of these organizations were able to focus on new subjects and styles. Reid, for example, turned to subjects inspired by his upbringing on a farm in rural Ontario. His work, Mortgaging the Homestead (1890), envisions a moment from his childhood in which his family was forced to mortgage their farm, a necessity in hard times that meant a family giving up control over their land and their future. The subject was deeply compelling for an Ontario audience aware of the stigma of failure that was attached to the process. Instead of the rugged and sweeping landscapes that dominated Canadian painting throughout the 19th century, artists such as Reid and fellow OSA artist Paul Peel turned to more intimate subjects, such as these domestic scenes.

VIEW GEORGE REID’S MORTGAGING THE HOMESTEAD HERE

Figure 9.4 George A. Reid, Mortgaging the Homestead, 1890. Oil on canvas, 130.1 x 213.3 cm, National Gallery of Canada

Both the RCA and OSA are examples of artists coming together to address what they saw as a gap in art production support in Canada. The turn towards developing Canadian styles and subjects was artist-led, though this focus was soon overshadowed as both the RCA and OSA became formalized from artist associations into institutions—the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario—which influenced the direction of art in Canada through funding and exhibition. For example, the National Gallery of Canada was quick to support the work of the Group of Seven as a marker of national identity. The RCA’s inclination towards a modern, Canadian style can be considered a stepping stone towards the National Gallery of Canada’s aim to create a cohesive history of art in Canada. Ordering the works of artists such as John A. Fraser, to George Reid, to the Group of Seven parallels a development in which European visual modes applied to Canadian subjects for a European audience, to European visual modes applied to Canadian subjects for a Canadian audience, and then to modern Canadian visual modes of Canadian subjects for a Canadian audience.

The artists who formed the Group of Seven came together early in their careers through their employment at commercial design firms. It was while working at Toronto-based design firm Grip Ltd. that Tom Thomson, J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Frank Johnston and Franklin Carmichael first met and discovered their common artistic interests. The artists began taking weekend sketching trips together, and would often gather informally at Toronto’s Arts and Letters Club to socialise and discuss new directions for Canadian art.

A similar coming-together of artists occurred across Canada throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries that reflected both emerging national and more regional concerns. As settlements became cities and regions were folded into Canadian Confederation as provinces, settler artistic production began to increase. For example, the 1890s saw a flourishing of art and artists in what is now known as Alberta. (To give you a sense of the growth in the West, in 1906 Calgary and Edmonton each had a population of approximately 14,000; by 1914 it was 72,000.) In 1909 the Calgary Agricultural Exhibition held a display of more than 200 works by notable Canadian and European painters, including William Brymner and George Reid. In 1912 this event became the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede.

The Group of Seven influenced the development of art in the Canadian West. In the 1920s, its members Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer and J.E.H. MacDonald traveled to the Rockies. In 1928, the Calgary Museum displayed an exhibition of Group of Seven paintings. Many painters from the region went to the Ontario College of Art to study under Group of Seven painters. Harry Hunt, president of the Calgary Art Club, began collaborating with the National Gallery of Canada to establish an Alberta Society of Artists to select works to exhibit nationally.

However, not all artists embraced the style of the Group of Seven, whose own approach to painting was less interested in naturalistic representation or realistic approaches to painting and towards a more abstract formal exploration. A.C. Leighton, for example, a British-born and -trained painter who settled in Canada, was interested in painting the extraordinary landscape of the Rocky Mountains in traditional English modes. In 1931, A.C. Leighton formed the Alberta Society of Artists and was its first president. A work such as Mount Skoki, painted in 1935, is closer in formal style to the work of John A. Fraser—think of his 1873 A Shot in the Dawn—than to the geometric, colourful, and bold forms of land painted by the Group of Seven; a good comparison being J.E.H. MacDonald’s Goat Range, Rocky Mountains (1932). Both paintings are detailed renderings of the land informed by a careful study of form and light. MacDonald’s image of the Rockies reveals his graphic arts training with its emphasis on dark outlining and mountain formations turned into almost-abstract triangular forms, while Leighton’s much more detailed and realistic portrayal is more academic in style. It is perhaps no wonder then, that this painting gained Leighton acceptance into the RCA in 1935.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.2

The following excerpts come from the introduction of art historian Anne Whitelaw’s Spaces and Places for Art. This book examines the development of art institutions in western Canada from 1912 to the 1990s. Western art museums and art associations were initially dependent on loan exhibitions from the National Gallery of Canada, but art galleries across the western part of the country gradually began to build their own collections and exhibitions, forming organizations that made them less reliant on institutions and government agencies in Ottawa.

On a cold night in late October 1924, hundreds of Edmonton’s citizens made their way to the Palm Room of the city’s lavish Hotel Macdonald to view the first exhibition of the newly formed Edmonton Museum of Arts. is inaugural display featured sixty works from local collections as well as twenty-four paintings on loan from the National Gallery of Canada, all of which, according to press reports, were received enthusiastically by the public. e inclusion of works from the National Gallery’s collection was not an unusual occurrence for a new art organization trying to establish its legitimacy in what was still viewed as a relatively remote part of the country: the Winnipeg Art Gallery, founded in 1912 and the only other art gallery west of Toronto in 1924, was similarly dependent on National Gallery loan exhibitions for its ongoing activities, as were the art associations of smaller communities such as Brandon and Moose Jaw. Instituted in 1913, the loan exhibition program was one of the primary means by which the National Gallery was able to overcome the limits of its location in Ottawa and achieve its mandate of building Canadian public interest in the fine arts and promoting the nation’s artists. Closely following the passing of the National Gallery of Canada Act in 1913, its director, Eric Brown, justified the establishment of the loan exhibition program as being the best way to demonstrate the quality of Canadian art and to encourage individual Canadians to purchase in that area. Brown also argued that loan exhibitions would ultimately encourage the formation of art societies and institutions across the country, thereby increasing the appreciation and collecting of Canadian art.

The loan exhibitions are just one example of the complicated relationship between the National Gallery and art organizations in western Canada that this book explores. While the loan exhibitions mutually benefited both the national institution and regional galleries, they also became sources of tension as art organizations in the west sought more influence over the content of the exhibitions and the manner in which they travelled from centre to centre. The National Gallery, for its part, fought to maintain control over the kinds of work that circulated from its collections and to manage the movement of the exhibitions across the country. Over the roughly eighty years covered by this book, art galleries in western Canada both relied upon and resisted the leadership and assistance given by the National Gallery and other federal or federally funded institutions.

Whitelaw continues on to explain:

Arts organizations emerged in western Canada at about the same pace that cities developed in the region, with public galleries usually being formed by societies of either artists or art lovers as soon as some form of support from civic government – whether financial or in-kind – could be obtained. The Winnipeg Museum of Fine Arts (now the Winnipeg Art Gallery) was established in 1912 as a result of the activities of the Manitoba Society of Artists and the Western Art Association (formerly the Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada), and after spending its formative years in the city’s Industrial Bureau, it was housed in Winnipeg’s newly erected Civic Auditorium from 1933 until its current building opened in 1971; the Edmonton Museum of Arts (now the Art Gallery of Alberta) was established in 1924 by a group of private citizens with the support of the Edmonton Art Club and moved frequently until erecting its own building in 1968; the Vancouver Art Gallery was founded through the generosity of some of the city’s leading citizens who raised enough funds for a building as well as a collection of mostly British paintings in 1931; in Saskatchewan, the Saskatoon Art Centre, founded in 1944, afforded meeting and exhibition space to the Saskatoon Art Association, the Camera Club, and the Archaeological Society until funds and a significant donation of artworks from businessman Frederick Mendel made possible the construction of a permanent building – what would become the Mendel Art Gallery – in 1964; the Norman MacKenzie Art Gallery was finally opened at the University of Saskatchewan’s Regina College in 1953, seventeen years after Norman MacKenzie’s bequest of a significant portion of his collection and funds for a building; also in Regina, the Public Library’s chief librarian Marjorie Dunlop began to organize art exhibitions in the periodicals reading room in 1948 and successfully advocated for the inclusion of an art gallery in the new public library building, erected in 1964; the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria opened in 1951 but the Island Arts and Crafts Society had presented exhibitions in the city since 1910; and while the Glenbow Museum is currently Calgary’s principal collecting institution, from 1939 to its sale in 1960, Coste House was home to many of the city’s art and theatrical societies, exhibitions, as well as the first site of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (what would become the Alberta College of Art and Design). Meanwhile, artists and interested amateurs formed art societies in smaller towns across western Canada, many of which found spaces for exhibition of their members’ works in library and community halls, spaces that also displayed traveling exhibitions from the National Gallery or smaller shows organized by art galleries and museums in the regions’ larger centres. (Whitelaw 2017, 3-6)

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.3

Artist organizations and associations in Ontario throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries supported many facets of artistic development, namely: education, display, and commercial sales. This focus, which in many earlier art historical texts is mapped out as a progression of art-making in Canada that culminates in the establishment of the National Gallery of Canada and the work of the Group of Seven, often marginalizes the many associations that emerged in the same period that did not fit within this progression and nationalist outlook. The development of modern art in the early 20th century in Canada is also a story of artist organizations and groups who were less concerned with nationalism and in many cases challenged the conservatism of the RCA and/or were intent on participating in international artistic trends.

In 1920, Montreal was a busy commercial centre, far ahead of Toronto, but conservative in matters of art; with few exceptions, local critics and collectors still preferred European, more academic artistic styles. In this milieu, a selection of former students of artist William Brymner at the Art Association of Montreal pooled their resources and rented a house at 305 Beaver Hall Hill. The upper floors were individual studios and the main level, their exhibition space. The Beaver Hall Group, as the artists became known, were supported by A.Y. Jackson (their first president), and were a non-structured association of artists including Mabel May, Lilias Torrance Newton, Randolph Hewton, Edwin Holgate, Mabel Lockerby, Anne Savage, Emily Coonan, Adrien Hébert, and Henri Hébert. Prudence Heward was loosely affiliated with the Group but did not share space at Beaver Hill or participate in the first major Beaver Hall Group exhibition in 1921. The Group was short-lived, disbanding in 1923, but the friendships and alliances that formed lasted into the 1930s and 40s. Like many artist associations in Canada, the group formed out of friendships, but supported each other as artists—much needed given the still-developing art scene in Montreal—and shared a dedication to modernist approaches to art-making. As a group, they were not fervently committed to a single subject or nationalist view like the Group of Seven who formed in the same year; they are nonetheless now best known for their emphasis on figurative and urban subjects.

What made the Beaver Hall Group particularly remarkable was that almost exactly half of its members were women at a time when most professional artists in Montreal were men. In fact, as time wore on, the Beaver Hall Group was often characterized (mistakenly) by scholars as a group of women artists. The critical literature on the group is thin and up until recently they have received little notice. However, beginning in the 1990s a number of the Beaver Hall artists were rediscovered by female academics, some of whose scholarship focused solely on the female members of the group, contributing to the notion that the group was dominated by women artists (Meadowcroft 1999; Walters 2005). This view was revisited and critiqued in the somewhat recent touring exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1920s Modernism in Montreal: The Beaver Hall Group in 2015 (Des Rochers and Foss). Given that women have historically been overlooked in art history, it is perhaps no wonder that feminist art historians used the Beaver Hall to attempt to correct this oversight.

Watch the following NFB documentary, By Woman’s Hand (1994, 59 min), for more on some of the women artists involved with the Beaver Hall, through the eyes of Prudence Heward, Sarah Robertson and Anne Savage.

In an essay on Beaver Hall member Anne Savage, Katrie Chagnon and Elisabeth Otto address the miscategorization of the Savage and her colleagues:

This reassessment takes place in light of recent scholarship questioning the ideological and gender-based opposition between the Group of Seven and the Beaver Hall Group stemming from discourses on painting of the 1920s and 1930s. Indeed, for many years, Canadian art historians fostered the dichotomy between the manly aesthetic of the Toronto-based Group of Seven, focused on the idea of wild and uninhabited nature, and the supposedly “humanized,” individualized and thus feminized aesthetic of the Montréal-based Beaver Hall Group, of which Savage was a member. Seen by feminist art historians as a counterpoint to the “macho ‘bushwhacking’ that surrounded the Group of Seven,” the vision of nature espoused by Savage and her colleagues (including Mabel Lockerby, Mabel May, Kathleen Morris and Sarah Robertson) is often seen as contributing to the creation of an idyllic image of the Québec countryside, to the extent where it has often been equated with a nostalgic form of regionalism (n.d.).

Figure painting was definitely the prerogative of Montreal artists during the early 1930s. Ontario-born, Montreal-based Edwin Holgate was best known for his portraits and nude figure studies. He was one of the “elders” of the Beaver Hall Group of painters. Holgate was fluent in French and was introduced to Montreal’s francophone literary circles, which helped him access collectors; he was able to cross the cultural barriers between French and English Montreal, and his influence was felt in both communities. After leaving Ontario, he studied at the Art Association of Montreal with William Brymner and then Maurice Cullen before travelling to Paris to further his studies. Holgate returned to Montreal in 1914, travelling via Russia and Japan to Victoria, due to the outbreak of the First World War. He enlisted in the Fourth Canadian Division and served in the ranks until 1919. He was a key figure in the Beaver Hall Group, and in 1928 started teaching graphic art at the École des Beaux-Arts. His work was included in several Group of Seven exhibitions, and he became a member in 1929. Holgate was also a member of various social and professional groups, including the Canadian Group of Painters, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, the Casoar-Club, and the Pen and Pencil Club. His most notable works, like Edwin A. Sherrard at the Violin (1934), demonstrate an individual approach to portraying the human figure, a method that reveals the ascendancy of modernist figure painting over the traditional portrait image (Paikowsky 135).

VIEW LILIAS TORRANCE NEWTON’S SELF-PORTRAIT HERE

Figure 9.10 Lilias Torrance Newton, Self-portrait, c. 1929. Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 76.6 cm, National Gallery of Canada.

Edwin Holgate and Lilias Torrance Newton worked to revitalize art education at the Art Association of Montreal. You can read more about Lilias Torrance Newton on the National Gallery of Canada’s website. In her Self-Portrait from the late 1920s, Newton applies her skills as a modernist painter of individual character to herself. She portrays herself as independent, modern and sophisticated—an example of the new progressive Canadian woman. Her direct gaze and composed facial expression command the viewer’s attention. In contrast to the Group of Seven in Toronto, the Beaver Hall Group offered an alternative, more progressive view of modern art. Brian Foss has noted that the Beaver Hall was, broadly put, an inclusive collection of artists (unlike the Group of Seven). They encouraged women artists and validated their work and the group featured both Francophone and Anglophone artists, bridging a divide in the Montreal scene (Carleton, n.d.). While the Beaver Hall artists were diverse in their subjects and handling of paint on canvas, they did share a preference for striking colour masses and strong sculptural forms. They were urban artists who painted what they saw in the city and its inhabitants with a modernist spirit.

Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) catalogue 1947-48

An outgrowth of the Group of Seven, the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) formed in Toronto in 1933 and disbanded in 1969. It brought together many of Canada’s most recognized artists such as B.C. Binning, Jack Bush, Emily Carr, Charles Comfort, Paraskeva Clark, Prudence Heward, Yvonne McKague Housser, Jock Macdonald, Pegi Nicol MacLeod, and Isabel McLaughlin, among others. The CGP regarded itself as a successor to the Group of Seven, “to encourage and foster the growth of art in Canada which has a national character.” Although landscape continued to be the dominant subject among the members of the group, the CGP did encourage modern ideas, techniques, and subjects. As Alicia Boutilier writes,

[f]ar from being an end or transit point, the CGP was considered by many at the time to be a “vital force.” What made it such a force was its engagement with modern life–in subject matter, artistic approach and social activity–against a background of the Depression, World War II, postwar reconstruction and the Cold War. In the spirit of the times, the CGP sought a national bond, while at the same time displaying a progressively internationalist outlook. It was part of the move toward greater cultural organization in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s and participated in the expanding social consciousness of the period (Boutilier 11).

There were good reasons to form a new group. President Lawren Harris wanted to fill a need in Canada and form a group that could counter the Royal Canadian Academy. The CGP also sought federal support; even though it seemed like a long shot in the Depression, they sought financial support for shipping and packing artworks for exhibitions, which was their main focus.

VIEW PEGI NICOL MACLEOD’S SCHOOL IN A GARDEN HERE

Figure 9.11 Pegi Nicol MacLeod, School in a Garden, c. 1934. Oil on canvas, 112.4 x 99 cm, National Gallery of Canada.

Many of the key figures in the CGP saw themselves and their artistic tendencies as more in line with international, largely European art movements; Pegi Nicol MacLeod was one such artist. Born in Listowel, Ontario in 1904, she studied at the Ottawa Art Association and at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal in the early 1920s. During this time, she won five medals for her exceptional work, including the Willingdon prize for the landscape The Log Run in 1931. She joined the CGP in 1937, the same year she married and moved to New York. MacLeod’s artworks stand out from those of her contemporaries like the Group of Seven, whose experimentations with Post-Impressionism produced paintings that today almost seem retrograde. In life and in her art making, MacLeod was a bohemian whose emphasis on freedom is borne out in the very way in which she executed her paintings. In a 1947 letter to painter Jack Humphrey, McLeod wrote: “Art should be freedom; its essence is freedom; Rules, laws, controls, standards—these works smell of the academy (power, lust to dictate)” (Murray 270).

Her modernist self-portraits, figure studies, paintings of children, still-lifes and landscapes are characterized by a fluidity of form and vibrant colour. MacLeod’s paintings are typified by their expressive flowing brushwork verging toward abstraction. There were few artists working in Canada alongside MacLeod who captured the vivacity, movement, and dynamism of people and life as she did (Smither 67). Many scholars have noted that MacLeod’s interest lay in modernist developments in contemporary painting and that her technique and style had no equivalent during her lifetime.

Throughout her bohemian and vibrant social life, painting remained MacLeod’s focus as she gradually developed her unique style. An active member in the CGP, her career was supported by Eric Brown, the first director of the National Gallery of Canada, who arranged for many of her paintings to be included in a CGP exhibition after she had moved to New York City in 1937. School in a Garden was completed in Ottawa just prior to her departure. One of a series of studies of children working in the school garden across the street from her parents’ Ottawa house, the painting reveals the sinuous, flowing arabesque brushwork which is a signature of her artistic style.

MacLeod did not obey convention. Her friends and fellow free-spirited artists helped to nurture her independence, encouraging her willful experimentation—much to the chagrin of her mother, who disapproved of MacLeod’s artistic endeavours. Her friend Marjorie explained that it was not exactly her painting that bothered her parents: “It was more the way she painted that they could not understand. The books she read, the music she played, everything she thought and did was contrary to their conditioning” (Brandon 32). MacLeod’s artworks were praised during her lifetime; however, being a woman artist with a modern artistic style that defied convention meant that MacLeod was overlooked for decades by those writing the first textbooks on art history in Canada. More recent critical examinations of how the artistic canon has been produced and reproduced has renewed attention in MacLeod’s singular paintings.

LEARNING JOURANL 9.4

Research one of the artists from the Beaver Hall Group or Canadian Group of Painters. Research one of their artworks, and write a paragraph or two (200-500 words) visually describing and analyzing it.

Imagined communities

Historically, war is a time of innovation and resourcefulness. In the recovery from war there is often a period of stability that leads to a continuance of industriousness—but of course it can’t last for long. After the First World War (1914-1918), Canada was productive economically and culturally—we see this in the 1920s with the emergence of so many artistic developments: the Group of Seven’s first show in 1920; the Beaver Hall exhibition of 1921; and the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art in 1927, to name only a few. Stability is difficult to sustain, however. The stock market crash of 1929 officially signalled the beginning of the Great Depression, which began a 12-year economic slump that affected all of the Western industrialized countries. From 1930 to 1933, the Canadian economy suffered a rapid collapse, and the recovery that eventually followed was slow. In some respects, the Second World War (1939-1945), which Canada entered to support Britain, brought Canada and the world out of the Great Depression. The Second World War was instrumental in defining Canada, transforming the country from a relatively overlooked country on the periphery of global affairs into a critical player in the war, one of the 20th century’s most important struggles. New initiatives were developed after 1945 to foster a sense of national cohesion. In this next section we will look at one project—The National Film Board of Canada’s (NFB) Still Photograph Division—mandated by the federal government to promote the nation.

Benedict Anderson’s now-seminal book Imagined Communities, first published in 1983, reshaped the study of nations and nationalism. In his book, Anderson asks what we mean by “nation” or “nationalism;” according to him, these are not natural, but relatively modern, phenomena. According to Anderson’s definition nations and nationalism are “imagined communities,” made up of groups of people who see themselves as belonging to the same community, even if they have never met, and otherwise may have nothing in common. Anderson argues that the nation is inherently limited in scope and sovereign in nature. It is imagined because the actuality of even the smallest nation exceeds what it is possible for a single person to know—one cannot know every person in a nation, just as one cannot know every aspect of its economy, geography, history, and so forth. Anderson’s approach emphasizes the material conditions that shape culture as well as the institutions that facilitate its reproduction—from newspapers and novels to censuses, maps, and museums. He writes: “the birth of the imagined community of the nation can best be seen if we consider the basic structure of two forms of imagining which first flowered in Europe in the eighteenth century: the novel and the newspaper. For these forms provided the technical means for “re-presenting” the kind of imagined community that is the nation” (Anderson 2006, 24-25).

In Canada, both the National Film Board (NFB) and its Still Photography Division were instrumental in the creation of an imagined community. The NFB’s Still Photography Division was just that, a division of the larger NFB, which had been established in 1939 by an act of Parliament as an “advisory body rather than a production house, yet it was granted extensive powers over other governmental film work including advising on production, financing, distribution, and liaison within and beyond the government” (Payne 2013, 20). In 1941 the Still Photography Division of the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau was transferred to the NFB. Art historian Carol Payne writes of the directive of the Still Division:

From the earliest days of the NFB, the question of national unity had been central to its mission and, accordingly, that mandate extended to Photo Services. Because the NFB was founded in 1939 and shortly became known for wartime films, it may appear to have been formed largely in response to the dramatic events of the Second World War, but the archival record tells a different story. The National Film Act of 1939 prioritized anxieties around Canadian unity over concerns about the war. The Film Act charged the government film commissioner with “the making and distribution of national films designed to help Canadians in all parts of Canada to understand the ways of living and the problems of Canadians in other parts” (Marchessault 1995, 131-46). The mandate, which echoed the NFB’s emphasis on cinema (and photography) as a means for “one part of Canada . . . to know . . . other [parts of Canada],” would be reiterated throughout the NFB’s history and accentuated by its leaders, including [John] Grierson. Indeed, it became such a prominent rallying cry that it would be echoed by staff for years. In a 1996 interview, long-time photographer Gar Lunney, for example, reiterated that rhetoric proudly, announcing, “Our job . . . in the National Film Board, as I understand it, was: to show Canada to Canadians” (Payne 2013, 21-23).

Documentary filmmaker Bob Lower examines the ways that the NFB represented Canada to Canadians in his 2014 film, Shameless Propaganda. Lower watched 400 films created by the National Film Board of Canada in order to make his own documentary about the NFB that demonstrated a self-awareness about the ways the NFB produced information.

Watch this short NFB film from 1945 titled “Headline Hunters” (10 min) that chronicles the complex ways information about the war is recorded, edited, and distributed. As you watch the film, consider John Grierson’s famous quip, “Art is not a mirror, but a hammer.”

The NFB Still Photography division was intent on producing an “official” portrait of Canadian society, using images to construct an imagined community. “The Division commissioned its photographers to travel across the country, where they shot approximately 250,000 images of people, places, work, leisure, and cultural activities. Millions of Canadians as well as international audiences saw these photographs reproduced in newspapers, magazines, books, filmstrips, and exhibitions” (Agnes 2016). The Still Photography Division of the NFB was realized to tap into photography’s potential for reaching a large public through mass-circulation publications, particularly newspapers. The division produced representations using a common and accessible medium—photography—to capture images of the everyday. These images were powerful in part because they were so familiar, so widely available, and so unassuming: they formed a kind of backdrop to daily life in Canada.

Greirson used the growing collection of photographs to produce a form of editorial called a photostory. A photostory is a highly-crafted combination of text and image that often takes one idea or theme as its subject. For the NFB Still Photography Division, the main story was focused on Canadian civilian life during the war, and on what Canadian citizens and industry were doing at home to support the military. The photostory centers photographs as the primary source of information, with text supporting images instead of the other way around.

The NFB employed photographers to work somewhat independently in the field, loosely following assignments given to them. But the photographers were part of a much larger enterprise, including editors, writers, clients, and bureaucrats, and were considered only the partial authors of the final images. Editorial strategies such as cropping (excluding particular parts of a photograph), scale (placing large and small photographs alongside one another for emphasis), vantage (photographs of the same subject taken from various perspectives and angles), and considerations of balance, flow, pattern, and repetition worked to accentuate ideas and narratives within a photostory. Once completed, photostories would be circulated in various print media and magazines.

The NFB and photostories remained dominant until the end of the 1950s. By 1959, the NFB had amassed 13,000 negatives and made them accessible through displays and special projects. Though the war may have ended, the NFB photostories continued to perpetuate propagandistic values, serving the needs and mandates of government policy, particularly in fostering a sense of Canadian identity. As Payne’s study points out, the images and photostories reproduced for a collective audience via mass media publications were celebratory and optimistic. Taken together, the NFB’s Still Division photographs create a composite portrait of Canada made from nationalistic and bureaucratic points of view and aspired not just to present an image of the country, but the image. As a result, the NFB holds a unique position in the history of Canadian visual culture as a conveyor of shared values and governmental programs in photographic form.

The National Gallery of Canada now has a searchable database of over 800 photostories, created between 1955 and 1971 by the National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division, which you can explore here.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.5

What is happening in the photostory above? Think about how the images work together visually (are some bigger, are some higher on the page than others, what narrative does this create)? Who put this story together? Who is photographed and how? Who is its intended audience? How is text used to support the images? If the NFB’s mandate is to show Canada to Canadians, what is being demonstrated in this photostory?

The Government of Canada and the National Film Board used visual images to unite and mobilize Canadians during the war, and to foster an ongoing sense of Canadian identity. At the same time that photographic images were increasingly used as political tools, artists too were moving away from representation towards abstraction. This shift was a reflection of the ways, in part, that photography filled the need for representational images, freeing up artists to move towards expression. Both, however, were intimately tied up in the political. In Canada, particularly in Quebec, abstraction emerged as a response to tense political contexts and identities that refuted the representational, which artists viewed as restrictive and stifling to political and artistic advancement.

The rise of abstraction and the Automatistes

Watch The Art Assignment video “The Case for Abstraction” (9 min) below:

As “The Case for Abstraction” outlines, abstract or non-objective art uses forms such as geometric shapes or gestural marks which have no source at all in an external visual reality. Since the early 20th century, abstract art has formed a central stream of modern art. The artists who were the pioneers in Canada exploring abstraction often used nature-based subject matter. They took as images landscape, the body, and nature, filtered through methods we still think of today as abstracting—summarizing, subtracting, and stylizing. Relatively speaking, Canadians were late to abstraction. In Canada, Kathleen Munn was the first artist to exhibit abstract, Cubist-inspired paintings in 1923. Early women abstractionists were given little credit in early accounts of art history, and recent renewed interest in artists like Munn, Edna Taçon, and Marian Scott has worked to correct this oversight. Watch the Art Canada Institute preview video for their online book on Kathleen Munn to learn more:

A few years later, Bertram Brooker was the first Canadian artist to hold a solo exhibition of abstract work in 1927 in Toronto at the Arts and Letters Club. To his dismay, the works in view were not received well; especially hurtful were the reactions of his friends and supporters, J.E.H. MacDonald and Arthur Lismer, who could not understand his process and approach. Watch the Art Canada Institute preview video for their online book on Bertram Brooker to learn more:

Artists like Bertram Brooker and Kathleen Munn were influenced by the latest modern art trends happening in the US and Europe, and in their experiments in abstraction they, too, explored the process of separating qualities or attributes from the individual objects to which they belong. The forms these painters used were often blocky, solid, and three-dimensional; they used colour as an expression of mood, musical feeling, or ideas rather than a reflection of the natural world. Art historian Joyce Zemans observes that this “first generation of English-Canadian abstractionists came to maturity at a time when the nationalist discourse of the Group of Seven dominated Canadian art. Artists who chose a different path struggled for critical and institutional support” (2010, 163). It is difficult to pinpoint where and when abstraction began to gain ground as an approach to art making in Canada, and, because abstraction was a tentatively grasped idea that led to numerous strands of development, it is impossible to characterize Canadian abstraction as a cohesive movement. As a result, the efforts of these breakthrough artists in the 1920s and 30s are best defined as individual approaches to abstraction. The first collective of abstract artists in Canada exploded onto the scene in Quebec in the 1940s with the Automatistes.

In 1946 artist Claude Gauvreau pronounced, “At last! Canadian painting exists.” He was referring to an exhibition of works by painter Paul-Émile Borduas and some of his disciples in Montreal. These artists came to be known as the Automatistes and would revolutionize art-making in Quebec, making works that could stand up to both New York and Paris (Nasgaard 53). The Automatistes were the first artists to embrace avant-garde gestural abstraction. Gathered under the leadership of Paul-Émile Borduas in the early 1940s, they were inspired by stream-of-consciousness writings of the time and approached their works through an exploration of the subconscious.

The Automatistes were united by their sympathies for European abstraction and outrage over Montreal’s pervasive cultural and political conservatism. The group comprised not just visual artists, but also included dancers, playwrights, poets, critics, and choreographers. Members included Marcel Barbeau, Marcelle Ferron, Roger Fauteux, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Pierre Gauvreau, Louise Renaud, and Jean-Paul Riopelle.

The Automatistes’ leader, Paul-Émile Borduas, had originally aspired to be a church decorator, and apprenticed with one of the forefathers of Quebec art, Ozias Leduc, a distinguished painter who is best known for his extensive religious work in churches. Leduc encouraged Borduas to go to Paris in 1928 to study art with Maurice Denis, a French artist who was devoted to reviving Catholic religious art by recasting its traditional iconography in a more contemporary language—not exactly the most progressive teacher when we consider some of the other radical avant-garde art movements going on in Europe. When Borduas returned to Quebec, there was little church decoration work to be found because of the onset of the Depression in 1929. Instead, he began teaching young children in the Catholic School Board in Montreal, dropping off of everyone’s radar. However, Borduas later recalled of this period that working with children re-established his feelings about art and helped him “unblock his creativity.” Children, he wrote, thus “opened wide for me the door to Surrealism and automatic writing” (Nasgaard 60). He emerged in 1937 to teach at the École du meuble in Montreal. There he joined the intellectual company of colleagues like the art historian Maurice Gagnon. In the early 1940s Borduas began to form strong relationships with his students and with other younger intellectuals, artists, writers, and dancers. Borduas and his followers, including Marcel Barbeau, Jean Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, and Jean-Paul Mousseau, met in Borduas’s studio to discuss Marxism, surrealism and psychoanalysis, all subjects disapproved of by the church. Together the group discussed art, life, and politics, and began to reject the Catholic Church, which maintained a firm grip on francophone life and culture.

Preeminent Borduas scholar François-Marc Gagnon writes of the artist’s early foray into abstraction,

[Borduas’s] style was still figurative [in the late 1930s] and betrayed the influences of his Parisian masters, James W. Morrice and finally also Cézanne and Rouault. His discovery of the Surrealist movement and his reading of “Château étoilé” by André Breton (a text Borduas read in the review Minotaure and which eventually would become chapter 5 in Breton’s L’Amour fou) were decisive for his further career.

In this chapter Breton cited Leonardo da Vinci’s famous advice to his students to carefully look at an old wall until shapes and forms appear in its cracks and stains–shapes that the painter will only have to copy afterwards. This inspired Borduas to consider the piece of paper or the canvas on which he wanted to paint as a kind of psychic screen. By haphazardly tracing a few strokes, that is “automatically” and without any preconceived ideas, Borduas recreated Leonardo’s “old wall.” In this way he would only have to discover and refine arrangements in the drawing and, at a second stage, set them apart from the background by colour.

The art of pictorial automatism was born. Borduas’s first automatiste painting, if we are to believe him, was Abstraction verte in 1941. In 1942 he exhibited 45 “surrealist works” in gouache at the Théâtre de l’Ermitage in Montréal. This exhibition was a profound success. The year after, he attempted to transfer to oil the effects he had obtained in his gouaches, but not, however, without introducing important changes. To the dichotomy of drawing and colour which he had explored in the gouaches, he introduced the contrast of figure and ground. (Gagnon 2008)

Fernand Leduc had a central role in the development of ideas of the Automatistes between 1943-47. He was the first to suggest that the grouping of artists, writers, and dancers form a group and the first to propose they come up with a collective manifesto. The first time they were referred to as the Automatistes was in 1947, at an exhibition held in the apartment of the Gauvreau brothers, Claude and Pierre. Tancrède Martin reviewed the show and, inspired by Borduas’s Sous le vent de l’ile ou 1.47 (1947), he coined the group’s name.

VIEW PAUL-ÉMILE BORDUAS’S LEEWARD OF THE ISLAND OR 1.47 HERE

Figure 9.14 Paul-Émile Borduas, Sous le vent de l’île ou 1.47 (Leeward of the Island or 1.47), 1947. Oil on canvas, 114.7 x 147.7 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

READ Brian Foss’s object story essay on Borduas’ Sous le vent de l’île, in which he argues that the painting can be seen productively as a socio-political document as much as an ambitious work of fine art. Sous le vent de l’île is one of the earliest and most accomplished visual statements of the radical changes defining French Quebec between the mid-1940s and the Quiet Revolution of the early 1960s. Its automatist technique, its semi-abstract character, and its surrealist-inspired philosophy all became basic to French Quebec’s desire to overthrow the socio-political conservatism of “la grande noirceur” in favour of a society premised on individual freedom and creativity.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.6

The Automatistes shared a collective approach to art-making that emphasized a creative process without preconception. They believed that artists should draw what comes naturally to them and then give the work of art a title after it is completed. Using any art materials you have on hand—paper, canvas, paint, pencil, pencil crayon—attempt to create an artwork using the automatism technique, using Borduas’s method of drawing “what the mind sees.” Free your mind and let the image dictate where it goes. Once you feel it is completed, reflect on the experience of making your artwork.

Looking at your artwork, what do you think it represents? What did you like or dislike about this exercise and why? What was challenging and why? Why do you think artists were interested in creating art “without preconception”?

One of the most important legacies of the Automatistes was their anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto, Refus global. Refus global, or “total refusal” in English,went on to become one of the most important and controversial artistic and social documents in modern Quebec society. The incendiary text caused an uproar, and Borduas exiled himself, first to the United States and then to France. Refus global helped trigger the Quiet Revolution to come. The manifesto was written by the painter Paul-Émile Borduas and signed by 15 members of the Automatistes. It included texts by Bruno Cormier (later a psychoanalyst), poet Claude Gauvreau, painter Fernand Leduc and Françoise Sullivan (then a dancer). The manifesto was illustrated by Marcel Barbeau, Paul-Émile Borduas, Marcelle Ferron-Hamelin, Pierre Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Jean Paul Riopelle, and Maurice Perron, a photographer. Other signatories included Thérèse Renaud, Madeleine Arbour, Françoise Riopelle, Muriel Guilbault, and Louise Renaud. It was launched at the Librairie Tranquille in Montreal on August 9, 1948.

The passionately written rallying cry advocated a need for not just liberation but “resplendent anarchy,” vehemently challenging the traditional values of Quebec. One of its iconic lines was: “To hell with the holy-water-sprinkler and the tuque!” It also anticipated the coming of a “new collective hope.”

The Automatistes were directing their anger at the oppressive nationalism defined by the province’s premier, Maurice Duplessis. The 15-year period that his government was in power became known as “La grande noirceur” (the Great Darkness). Duplessis’s conservative Union Nationale party favoured private businesses and gave overwhelming control of both education and health care to the Catholic Church. It is also clear from its text that the signatories of Refus global railed against the Catholic Church, which was at the time very fundamentalist, defensive, and moralizing in terms of the French language and repressive customs and habits which lingered still.

Their manifesto claimed:

. . .The fatal disintegration of our collective moral strength into strictly individual and sentimental power has undermined the once formidable shield of abstract knowledge behind which society takes cover to enjoy its ill-gotten gains at leisure.

It took the last two wars to achieve this absurd result. The horror of the third war will be decisive. We are on the brink of a D-day of total sacrifice.

The rats are already fleeing a sinking Europe by crossing the Atlantic. However, events will eventually overtake the greedy, the gluttonous, the sybarites, the unperturbed, the blind and the deaf.

They will be mercilessly swallowed up.

A new collective hope will dawn.

It is already demanding the passion of exceptional insights, anonymous union in renewed faith in the future, in the future collectivity. . .

You can read the entire text of the anti-establishment manifesto Refus global here.

The effects of Refus global, the Automatistes’ anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto, rippled far and wide. It went on to become one of the most important and controversial artistic and social documents in modern Quebec society. The manifesto voiced the group’s desire for liberation and the ushering of a collective hope. The incendiary text caused an uproar in the media, leading to Bordaus’s firing from his teaching job at the École du Meuble. Borduas exiled himself, first to the United States, and then to France, where he died. Refus global helped trigger the Quiet Revolution to come.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.7

A manifesto is a strongly worded written statement declaring publicly the intentions, motives, or views of the author(s). What would your manifesto be? Draft a short manifesto about something you are passionate about.

Jean Paul Riopelle was another major figure of the Automatistes, a co-signer and cover designer of the manifesto; internationally, he is probably still the best known Quebecois artist. He studied at the École du Meuble, and while he achieved success in Montreal, it was his relationship with Paris that secured his reputation. He first visited Paris in 1946, and in 1947 he decided to settle there. He was included by André Breton and Marcel Duchamp in the last major group show of the Surrealist movement at the Galerie Maeght in 1947. His work of the 1940s and onward is characterized by a technique in which he squeezed paint directly from the tube onto the canvas, the paint’s threads trailing across the surface so that they criss-cross in a number of directions. From around 1953 Riopelle used a palette-knife, which we can see below in Pavane (1954)—here, the whole surface of his work becomes a mosaic of compact and varied palette-knife strokes that wedged together to form contrasting chromatic zones and movements.

The National Gallery of Canada describes Pavane and Riopelle’s style:

Jean Paul Riopelle was one of the most ambitious artists of the group “Les Automatistes”. The artist applied paint directly to the surface of the canvas using a palette knife, blending each mark in a free, abstract and automatic gesture. Space is created by the relationships of colours as they intersect or lay in close proximity to each other. This creates an animated surface, with some colours receding and some dancing forward. This monumental triptych was first exhibited in Canada in 1963 as part of the artist’s retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada, and its title refers to a Spanish dance that originated in the 16th century. The dance incorporates a stately and processional rhythm, which is captured in the energy and movement of this painting. (National Gallery of Canada, n.d.)

Watch this CBC clip from 1965 about Riopelle and his approach to painting:

The coming years brought Riopelle increasing success and immersion in the Parisian cultural scene. He spent his evenings in Paris bistros with friends, including playwright Samuel Beckett and artist Alberto Giacometti. In the 1960s, Riopelle renewed his ties to Canada. He had exhibitions at the National Gallery of Canada (1963), and the Musée du Quebec held a retrospective of Riopelle’s work in 1967. In the early 1970s, he built a home and studio in the Laurentians in Quebec and divided his time between France and Quebec.

A number of other artist collectives and groups emerged on the heels of The Automatistes. The Painters Eleven formed after a number of its members exhibited in a show at Simpson’s Department Store in Toronto, entitled Abstracts at Home. The Painters Eleven—Jack Bush, Oscar Cahén, Tom Hodgson, Alexandra Luke, Ray Mead, Kazuo Nakamura, William Ronald, Jock Macdonald, Harold Town, Walter Yarwood, and Hortense Gordon—introduced the kind of abstraction happening in New York to Canadian viewers.

Around the same time in Quebec, a second avant-garde formed. Les Plasticiens were Jauran (Rodolphe de Repentigny), Louis Belzile, Jean-Paul Jérôme, and Fernand Toupin, followed by Guido Molinari, Claude Tousignant, Yves Gaucher and Charles Gagnon. These painters made a decisive impact on art through their explorations of geometric abstraction developed both in Paris and in New York.

Artistic collaboration and collectivity continue to inform the work of many contemporary artists working in Canada today. The desire for artistic collectivity and collaboration has persisted into the late 20th and 21st centuries. There are numerous examples of groups and collectives in Canada like General Idea, Condé + Beveridge, Feminist Art Collective, FASTWÜRMS, Tennis Club, PA System, Neon Kohkom, 44.4 Mothers/Artists Collective, ReMatriate Collective, and Life of a Craphead, for example.

The desire for artistic collectivity and collaboration has persisted into the late 20th and 21st centuries. There are numerous examples of groups and collectives in Canada, including General Idea, Condé + Beveridge, Feminist Art Collective, FASTWÜRMS, Tennis Club, PA System, Neon Kohkom, 44.4 Mothers/Artists Collective, ReMatriate Collective, and Life of a Craphead, for example.

You can read more about contemporary art collectives in Canada in Alison Cooley and Daniella Sanader’s essay in Canadian Art, “Gang Up: 16 Great Canadian Art Collaborations.”

There are a number of Indigenous art collectives working in Canada today. OCICIWAN Contemporary Art Collective in the region of Edmonton supports Indigenous contemporary art, experimental creative practices, and innovative research. In Saskatchewan, Sâkêwêwak has been supporting Indigenous artists in the Regina area for more than two decades. The collective provides support to artists helping them to create, grow, and reach audiences. They hold an annual Storytellers Festival, as well as residencies, workshops, exhibitions, and performances.

Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTec) is another Indigenous collaboration and the brainchild of new media artist Skawennati Fragnito (Mohawk) and Jason Lewis (Cherokee), a digital media poet, artist, and software designer. AbTec “is an Aboriginally determined research-creation network whose goal is to ensure Indigenous presence in the web pages, online environments, video games, and virtual worlds that comprise cyberspace” (AbTec, n.d.). Their projects have included artworks, writing, lectures, workshops, residencies, and exhibitions. AbTec began with a project called CyberPowWow, a cutting edge online gallery and chat space for contemporary Indigenous art. Lewis and Skawennati fervently believe that cyberspace and virtual worlds should be (and need to be) self-determined places for Indigenous peoples to call home. These tenets also underpin much of Skawennati’s artworks.

Skawennati, TimeTraveller™

Cyberspace and the internet have the ability to build community and collectivity. Skawennati and Jason Lewis contend that cyberspace may be one of the remaining territories not impacted fully by the histories and claims of colonialism. They write:

Cyberspace—the websites, chat rooms, bulletin boards, virtual environments, and games that make up the internet—offers Aboriginal communities an unprecedented opportunity to assert control over how we represent ourselves to each other and to non-Aboriginals.

[…]

History has shown us that new media technologies can play a critical role in shaping how Western, technologically oriented cultures perceive Aboriginals. The camera, for instance, taught people that we all wore headdresses and lived in teepees. Cinema claimed that we spoke in broken English—if we spoke at all. The World Wide Web has offered us the possibility to shape our own representations and make them known. Traditional mass media such as newspapers, magazines, television, and film are expensive to produce and distribute and consequently exclude Aboriginal peoples. On the internet, we can publish for a fraction of the cost of doing so in the old media; we can instantly update what we publish in order to respond to misrepresentations, misunderstandings, and misreadings; and we can instantly propagate our message across a world-spanning network. And we don’t need to fight through any gatekeepers to do so (Lewis and Skawennati 2005).

Skawennati’s TimeTraveller™ is a multiplatform project that includes a website, a nine-episode machinima series, a set of digital prints, and a prototype action figure. TimeTraveller™ tells the story of Hunter, an angry young Mohawk man living in the 22nd century. Hunter is disillusioned with his life in an overcrowded, hyperconsumerist, technologized world where his traditional skills as hunter, warrior, and ironworker don’t seem to be enough to get him by. He decides to use his edutainment system—his TimeTraveller™—to embark on a technologically enhanced vision quest that immerses him in historical events significant to First Nations, such as the Dakota Sioux Uprising, the Oka Crisis and the occupation of Alcatraz Island. Watch TimeTraveller™ Episode 01 here:

David Gaertner, Professor in the First Nations and Indigenous Studies Program at the University of British Columbia, writes of TimeTraveller™:

TimeTraveller™ is a love story. It’s a piece of science fiction. It’s a history of colonialism and Indigenous resistance. But of all these things TimeTraveller™ is a story about media and remediation. This is not to say that this work is more of an aesthetic than political piece. It is to say, however, that the import of Skawennati’s politics is realized through the refashioning of “old media” in the new.

[…]

In Episode 01 Hunter sets his VR headset to travel back in time to Fort Calgary, Canada. The year is 1875 A.D. He arrives just as a group of colonialists are finding their seats: “It looks like there’s going to be a show,” Hunter remarks. Indeed, in his engagement with his own “new media,” the TimeTraveller™, Hunter inadvertently stumbles across the “new media” of the nineteenth century, a moving panorama.

One hundred and fifty years ago the moving panorama was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the world. Hundreds toured Europe, the United States, and Canada. Moving panoramas were composed of a series of contiguous scenes that scrolled past an audience behind a proscenium, which hid the machinery and the person turning the crank. Kerosene lanterns illuminated the “moving pictures,” while a “Delineator” narrated the story.

The moving panorama in TimeTraveller™ contextualizes Hunter’s VR and locates Skawennati’s piece itself within a layered history of “new media.” Skawennati imagines Hunter’s interface via a medium as novel to the twenty-first century as the panorama was to the nineteenth: machinima, an animated movie that uses computer or video game software to generate the characters and scenes. Then, through both her own medium, and the one she retroactively imagines for Hunter, Skawennati reimagines and refashions the 1863 Minnesota Massacre panorama in her own narrative.

[…]

Like CyberPowWow before it, TimeTraveller™ enacts visual sovereignty in the way that it inscribes Indigenous politics, identities, voices, and perspectives into the present, past, and future of screen culture, a medium that has historically worked to efface Indigenous presence. In engaging the past TimeTraveller™ re-positions Indigenous presence and future and imagines new spaces to create and share stories (Gaertner 2017).

TimeTraveller™, which was developed between 2008 and 2013, used the virtual world of Second Life as its platform, a cyberspace where users can create and activate avatars that is, by its very nature, a collective or communal space.

LEARNING JOURNAL 9.8

Take some time to go through the website for the Initiative for Indigenous Futures, a program described as “a partnership of universities and community organizations dedicated to developing multiple visions of Indigenous peoples tomorrow in order to better understand where we need to go today.” How are digital- and cyber-spaces used to encourage Indigenous youth and Elders to envision their own future on their own terms? Choose one example of a workshop, project from the archive, residency, or symposium to illustrate your answer. Lastly, think about the ways that this example engages the idea of collectivity and collectivism.

OBJECT STORIES

- Emma Hassencahl-Perley on O’Halloran’s Outfit (c. 1841)

- Brian Foss on Paul-Émile Borduas, Sous le vent de l’île ou 1.47 (1947)

- Hilary Doda on Bessie Bailey Murray (designer), Nova Scotia Wool Mural (1953)

References

Agnes Etherington Art Centre. 2016. “The Other NFB: The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division, 1941–1971.” https://agnes.queensu.ca/exhibition/the-other-nfb-the-national-film-board-of-canadas-still-photography-division-1941-1971/.

Anderson, Benedict. 2006 [1983, 1991]. Imagined Communities. London; New York: Verso.

Boutilier, Alicia. 2013. “A Vital Force: The First Twenty Years.” In A Vital Force: The Canadian Group of Painters, 11-31. Kingston; Oshawa: Agnes Etherington Art Centre; The Robert McLaughlin Gallery.

Brandon, Laura. 2005. Pegi By Herself: The Life of Pegi Nicol MacLeod, Canadian Artist. Kingston; Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Buis, Alena. 2012. “‘A Story of Struggle and Splendid Courage’ Anne Savage’s CBC Broadcasts of The Development of Art in Canada.” In Rethinking Professionalism: Women and Art in Canada, 1850-1970, edited by Janice Anderson and Kristina Huneault, 106-31. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press.

Carleton University. n.d. “Remembering The Beaver Hall Group – Canada’s Unsung Modernists.” https://carleton.ca/fass/2016/08/remembering-the-beaver-hall-group/.

Chagnon, Katrie, and Elisabeth Otto. n.d. “Anne Savage: A Latent Collection.” Ellen Gallery, Concordia. http://ellengallery.concordia.ca/annesavage/en/.

Cooley, Alison, and Daniella Sanader. 2016. “Gang Up: 16 Great Canadian Art Collaborations.” Canadian Art. June 27, 2016. https://canadianart.ca/features/gang-up/.

Cross, L. D. 2003. “Woven, Not Carved: The Pangnirtung Tapestries Are Northern Art with Global Appeal.” Arctic 56(3): 310-16.

Des Rochers, Jacques, and Brian Foss et. al. 2015. 1920s Modernism in Montreal: The Beaver Hall Group. Montreal; London; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Black Dog Publishing.

Gaertner, David. 2015. “Back to the Future: Sovereignty and Remediation in Skawennati’s TimetravellerTM.” Artexte. https://e-artexte.ca/id/eprint/27920/1/Skawennati-RealizingtheVirtual_ATimeTravellerExperience.pdf.

Gagnon, François-Marc. 2008. “Paul-Émile Borduas.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 21, 2008; last updated August 28, 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/paul-emile-borduas.

Gagnon, François-Marc, and Clayton Ma. 2006. “Refus global.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 11, 2006; last updated December 21, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/refus-global.

Goldfarb, Beverly. 1989. “Setting Up Shop (1960-1970): Early Days at the Pangnirtung Weave Shop.” Inuit Art Quarterly, republished online March 11, 2020. https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/setting-up-shop-(1960-1970).

Hickman, Deborah. 2002. “Tapestry: A Northern Legacy.” In Nuvisavik: The Place Where We Weave, edited by Maria von Finckenstein, 42-50. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Inuit Art Quarterly. 2022. “How 10 Inuit Artists Came Together to Weave an Olympic Tapestry.” Inuit Art Quarterly, January 19, 2022. https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/how-10-inuit-artists-came-together-to-weave-an-olympic-tapestry.

Issenman, Betty Kobayashi. 2007. “The Art and Technique of Inuit Clothing.” McCord Museum. http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/scripts/printtour.php?tourID=CW_InuitClothing_IK_EN&Lang=2.

Lee, Yaniya. “Forget Art Basel Miami Beach—Put on Your Puffer Coat and Head North to Toronto.” Vulture, November 29, 2018.