ACTIVISM

In fall 2017, Life of a Craphead (the art, film, and curatorial duo of Amy Lam and Jon McCurley), produced a series of performances in which they floated a life-size replica statue of King Edward VII, who ruled the British Empire in the first decade of the twentieth century, down the Lower Don River in Toronto, Ontario. The sculpture imitates the 15-foot bronze statue that sits in Queen’s Park adjacent to the Ontario Legislative Building in Toronto. This playful intervention is a work of activism that critiques “the persistence of power as it manifests in public art and public monuments—symbols that are often preserved in perpetuity, even when the stories we want to celebrate change” (Don River Valley Park). In this module, we will examine art that seeks to intervene in social, political, economic and environmental issues, going beyond an aesthetic statement to enact meaningful change.

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.1

Read the following three op-eds. What perspective does each writer take on this artwork? Do the writers support the premises in the work? Why or why not? What words do they use to characterize and describe the work (e.g., unpatriotic, rebellious, timely, activist, good, bad)?

- Murray Whyte, “King Edward, Down the Don River without a Paddle,” Toronto Star, November 3, 2017.

- Yaniya Lee, “Forget Art Basel Miami Beach — Put on Your Puffer Coat and Head North to Toronto,” Vulture, November 29, 2018.

- Makda Ghebreslassie, “Dumping Statue in the Don River a Statement about Colonialism, Performance Artists Say,” CBC News, October 29, 2017.

Toppling monuments

While Life of a Craphead’s work takes part in the debates that raged across Canada, the US, and Europe (among other places) in recent years, other controversial monuments have also been toppled in recent years. Christiana Abrahms, curator of an exhibition at Concorida University in Montreal, entitled “Protests and Pedagogy: Representations, Memories, and Meanings,” provides this concise overview of the recent backlash against public monuments spurred by protests around racial injustice:

The police killing of George Floyd, an unarmed African-American man in Minneapolis, United States, in early 2020 unleashed a wave of angry street protests led by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Huge anti-racism protests featuring tens of thousands of persons of diverse races and ages, that began largely in the United States, have brought attention to the proliferation of police brutality, systemic racism, and racial in/justice (Cheung 2020; Altman 2020).

The replay in the media of video that captured the arrest and slow, public killing of Floyd sent ripples across the world in the weeks and months that followed, spurring protests in Canada, Europe, and further afield (Bennett et al. 2020; Aljazeera 2020). As part of these manifestations, protestors have taken to demonstrating against statues and public monuments (MacDonald 2020; Selvin and Solomon 2020). These targeted monuments are viewed as heroizing persons associated with colonialism, slavery, and imperialism. Hence, protestors demand the removal of these symbols of slavery or colonial power. Monuments that have received the most vehement protestations are those representing historical figures, recognized slave traders or owners, or those viewed as having supported outright racist policies against Indigenous, Black, and other racialized people. In these protests, prominent public monuments have been pulled down, defaced, painted over, toppled, graffitied, reconfigured, restaged, and reimagined in myriad ways (Draper 2020; Togoh 2020).

Colonial figures, confederate generals, and slave traders across the United States, Great Britain, and Europe have received the brunt of protestations….In Canada, various statues of the first prime minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, were selected. A group protesting against police violence in Montreal, pulled a statue of MacDonald off its plinth such that it was decapitated as it crashed to the ground (CBC 2020).

Activists, demanding that these statues be brought down, say their aim is to change historical narratives and to remind people of the full and complex biographies of these heroized figures who actively participated in the often-genocidal marginalization of Black and Indigenous people and other people of colour. As David MacDonald writes, “These protests highlight the racism of these infamous figures, the racist societies that produced these representations and the ways these representations and these statues continue to both normalize and obscure settler violence and systemic racism” (MacDonald, 2020).

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.2

VIEW DAVID GARNEAU’S DEAR JOHN; LOUIS DAVID RIEL HERE.

Figure 11.2 David Garneau, Dear John; Louis David Riel, 2017. Performance.

While artists haven’t necessarily removed statues, they have staged activist interventions to address controversial monuments in public spaces. For instance, in 2017 David Garneau, a Métis artist, engaged with a statue of the former Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald in the performance work Dear John; Louis David Riel. In this work, Garneau comments on MacDonald’s role as architect of the residential school system in Canada and in the arrest and subsequent hanging of Riel for treason. In Dear John, Garneau takes on the persona of 19th-century Métis leader Louis Riel to create what he calls a “monologue” and a “dialogue” with the statue, which includes “a rant taken from his trial transcripts; there’s a pleading, moving through all these stages, these types of grief” as Garneau puts it (Balzer 2014).

VIEW REBECCA BELMORE’S QUOTE, MISQUOTE, FACT HERE.

Figure 11.3 Rebecca Belmore, Quote, Misquote, Fact, 2003. Graphite on cotton rag vellum, 45.7 x 134.5 cm (each panel). Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, ON.

Anishinaabe artist, Rebecca Belmore”s Quote, Misquote, Fact (2003) also responds to a statue of MacDonald. To create this three-part graphite on vellum work, Belmore made a series of rubbings from an inscription at the base of a monument to MacDonald in City Park in Kingston, Ontario—the city of MacDonald’s birth and where he was buried. By selectively removing words from various sections of the inscription, Belmore’s rubbings drastically change the meaning of the text. For Belmore, the statues of MacDonald offer a means to engage with current representations of history. Explaining the work, she states: “As someone who grew up with very little access to our history through the education system—I feel compelled to witness and articulate and in some way visually mark current history” (Agnes 2023).

In her interview with curator and communication scholar Christiana Abraham, art historian Charmaine Nelson speaks to the importance of public decolonial activism in Canada. She notes:

In general, most Canadians have no idea about the nation’s colonial history. They don’t understand how Canada became Canada; they don’t understand about Indigenous dispossession. They certainly don’t understand that we had at least two hundred years of transatlantic slavery where both Black and Indigenous people were enslaved in a province like Quebec, and Black people were enslaved from Ontario all the way to Newfoundland.

Therefore, our conversations about monuments as colonial are not based upon a full understanding of these contexts because we don’t know how to grapple with the complexity of colonial history. Some people can’t hold these two thoughts in their minds at the same time—Sir John MacDonald central in founding the nation of Canada and Sir John MacDonald central in the architecture of the residential school system and the death and harm of many Chinese male immigrants. They can’t hold these two thoughts at the same time (Abraham 2021, 10).

Given the lack of acknowledgement and understanding of colonialism in Canada, art offers one way forward—a means to engage with public historical record. The above examples of how artists have engaged with monuments speak to a few of the ways we can understand art as activism. This module examines a wide range of practices in this vein, showcasing different modes of engagement and ways that activism can and has functioned as a means of resistance and as a driver of social change. As such, the module makes the case for art as activism in a manner explained by artist Marcus Ellsworth, who describes art as “a bringer of change . . . a way to connect people, to engage people, to motivate and move people to action” (Ellsworth 2014).

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.3

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- explain how art can function as a form of activism

- describe how artists have used monuments to speak to contentious histories in North America

- analyze how artists have employed art as a means to address hegemonic understandings of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation (amongst other topics)

- discuss how artists have engaged with non-traditional materials as an effective medium for relaying activist ideas, including articulating anti-war sentiments and critique militaristic policies.

This module will take you:

Life of A Craphead Text 2 min, Video 4 min

Toppling monuments Text 37 min

Outcomes and content 5 min

Privilege: Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge Text 4 min, Video 4min

General Idea & AIDS activism Text 6min, Video 5.5 min

Violence meets vulnerability – Barbara Todd & Barb Hunt Text 10 min

Where Hope Meets Action: Black Lives Matter Text 45 min, Video 24 min

Learning Journals 10 x 20 = 200 min

Total: approximately 6.5 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 11.1 Life of a Craphead, King Edward VII Equestrian Statue Floating Down the Don River (2017)

- Fig. 11.2 David Garneau, Dear John; Louis David Riel (2017)

- Fig. 11.3 Rebecca Belmore, Quote, Misquote, Fact (2003)

- Fig. 11.4 Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, It’s Still Privileged Art (1975)

- Fig. 11.5 General Idea, AIDS (1987)

- Fig. 11.6 Barbara Todd, Security Blanket (1989)

- Fig. 11.7 Barb Hunt, Antipersonnel (1998-2010)

- Fig. 11.8 Natalie Wood, I Can’t Breathe (2019)

- Fig. 11.9 Bank of Canada, Ten dollar bank note (2018)

- Fig. 11.10 Letitia Fraser, Virtuous Woman (2019)

- Fig. 11.11 David Woods (design) and Laurel Francis (quilting), Preston (2007)

- Fig. 11.12 Sade Alexis, Rosemary Brown (2021)

Introduction to activism and art

The activist potential of art has long been debated in art history. A dominant trend within discussions of activist art, exemplified by publications such as But is it Art? The Spirit of Art and Activism (1995), is to focus on activist art in relation to the emergence of conceptual art and political movements in the 1960s and 1970s like the civil rights and feminist movements. However, recent publications such as Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader (2007) have sought to recognize the longer historical relationship between art and activism at heightened moments of social and political transformation, tracing this connection back to periods like the Paris Commune in 1871. More recent discussions in the field of activist art focus on collaboration as a key element of socially engaged art practice, including the analysis of relational practices in Relational Aesthetics (1998) by Nicolas Bourriaud and the examination of diverse artistic partnerships in Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (2004) by Grant Kester. Collaborative methods of practice are increasingly the norm in contemporary art. Such works prioritize process over object production and technical proficiency, as well as social engagement and community over artistic autonomy. At the same time, the spheres of contemporary art and activism are increasingly intertwined.

Privilege: Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge

Against the backdrop of ongoing debates over labour (including “women’s work” and developments in the labour movement), Toronto-based contemporary artists Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge have often engaged with trade unions in their art practice. Collaborating for more than thirty years, they have sought to bridge working communities and the art world through their projects. They have been recognized for their unique collaborative practice and their extensive collaborations with trade unions since the 1980s, resulting in the production of vibrant photographic compositions that critically reflect on workers’ conditions and histories of labour in Canada.

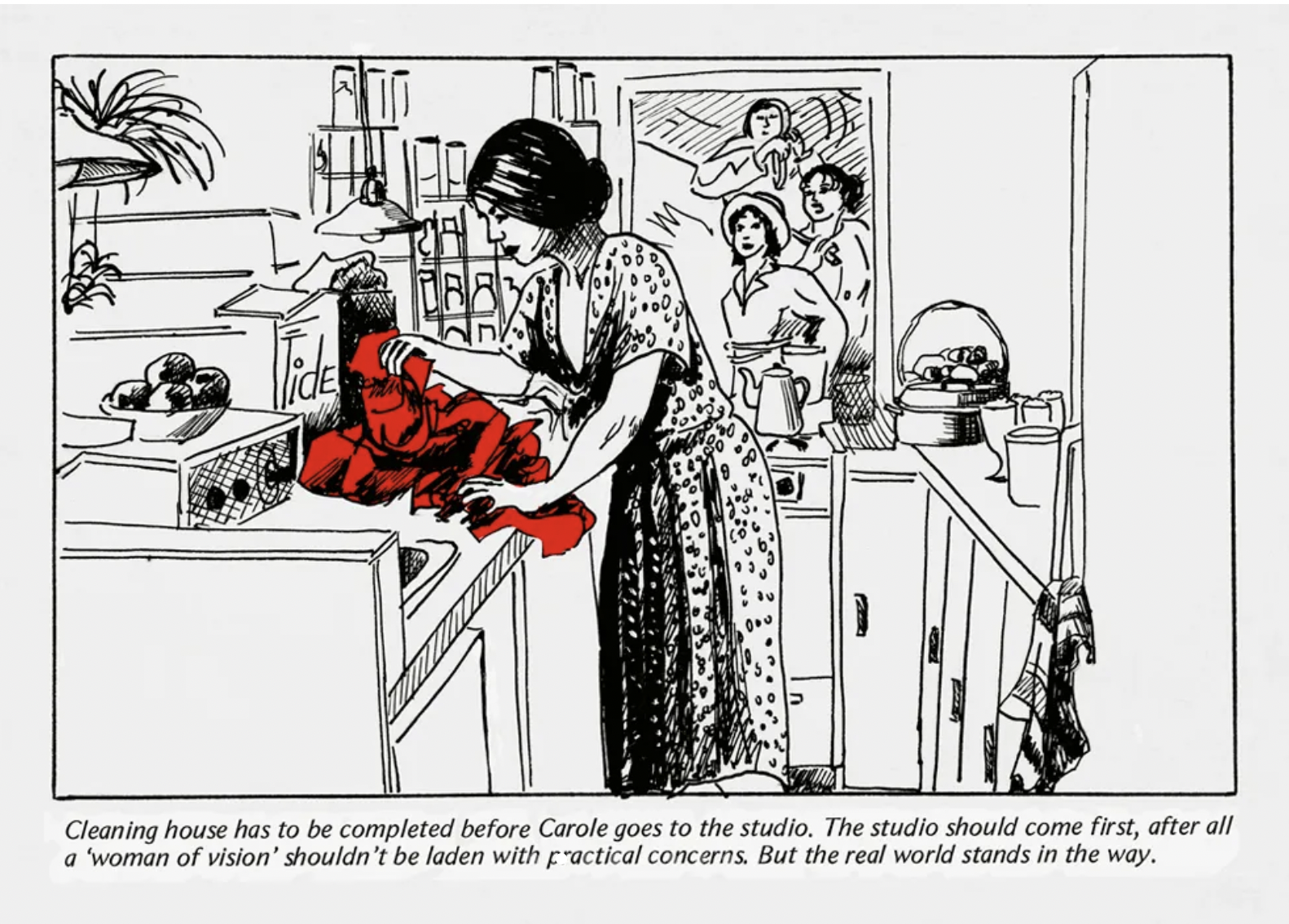

Art and activism often collide in the work of Condé and Beveridge. The two artists moved to New York City in the early 1970s with ambitions to have careers making minimalist sculpture. In the environment of the intensely competitive New York art market, they gradually realized that they were competing with one another for attention from dealers and curators, and that Condé’s work would automatically be considered secondary since she was a woman. Eventually, this realization led the artists to a complete break with their former minimalist practice, just at the moment when they had been invited to prepare a show of new work for the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). They turned away from the role of artist as individual creator for the art market, and began to instead work together as a collaborative team, developing a new role for artists as social citizens. Influenced by their relationship with the New York art scene (including the Art & Language group), in 1975 Condé and Beveridge created a series of new works which would comprise the 1976 AGO exhibition, It’s Still Privileged Art, which was subsequently exhibited at Canada House Gallery in London, in England. The show was charged by revolutionary iconography. It contained several silkscreen and photographic works based on the artists’ political involvement.

It’s Still Privileged Art was both the title of the AGO exhibition and one of the key works in the show. It’s Still Privileged Art took shape as a series of twenty-one illustrations in a stark representational style, in black and white, with bright accents of red. These drawings were exhibited and also formed a bookwork that took the place of a traditional exhibition catalogue. It’s Still Privileged Art is based on a series of conversations between the artists in 1975 that reflected critically on the nature of the art world and their place within it. These conversations address both the personal and professional roles of the artists and are in part playful, confessional, critical, and self-critical. Formally, the artists are quoting Soviet revolutionary iconography and Chinese comics of the period. Each scene is punctuated by a text caption explaining the narrative. One, for example, features Beveridge creating a minimalist work in the studio. The caption reads: “Karl sets up a new variation within a series of work that has preoccupied him for the past year. The work focuses on possible shifts of perception brought about by exclusively logical means.” Other scenes delve into the dynamics of a meeting with a curator, their interactions with a collector, and with their larger artistic community. Power relationships are foregrounded, for example in the depictions of the curator’s visit and the artists’ interactions with a collector, the latter depicting the successful sale of a drawing. Pivotal issues such as gender relations, the art market, and artistic labour are all addressed in It’s Still Privileged Art.

These key themes are in evidence in subsequent work by Condé and Beveridge, and continue to drive their practice today. It’s Still Privileged Art also marks issues of interest that the artists subsequently pursue in concrete ways through different labour organizations in Canada—including their work to develop banners for various unions and groups.

General Idea: Art addressing queer identity and the AIDS crisis

Another artist group that coalesced in Toronto in the same period as Condé and Beveridge was General Idea, initially an anonymous group that crystallized into an intentional three-part collaboration comprised of Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson. The group is well-known for their work addressing the discourse on AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s. Sarah E.K. Smith explains:

In the late 1980s AIDS was a taboo topic and a climate of fear surrounded the disease due to widespread and extreme homophobia. This was because initially the disease was thought to exclusively affect gay men. For instance, in 1981 the first article in the New York Times to address AIDS identified it as a cancer that only affected homosexuals. This was not helped by the fact that inaccurate and inflammatory information about the disease circulated widely in the media. Many aspects of the AIDS pandemic, including its scope and severity, were not at first understood. Tremendous prejudice—including within the medical community—was widespread given the initial impact of AIDS in the gay community and its sexual transmission. As such, there was a moral dimension to the AIDS pandemic that activists, as well as artists, sought to address. (Smith, 2016)

VIEW GENERAL IDEA’S AIDS HERE.

Figure 11.5 General Idea, AIDS, 1987. Acrylic on canvas, 182.9 x 182.9 cm. Private collection, Chicago.

Within this context, General Idea took a brazen approach to addressing the crisis, beginning with their 1987 painting AIDS produced for a fundraiser to benefit the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). This painting subsequently led the group to address the discourse on HIV/AIDS more broadly in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In AIDS (1987) the artists appropriated American artist Robert Indiana’s painting LOVE (1966), replacing the word “LOVE” with the name of the new disease. AA Bronson later noted that the ironic appropriation of Indiana’s work was in “bad taste. There was no doubt about that.” At the time, other artists, like Gran Fury, were addressing the disease didactically in their work, in contrast to the more ambiguous statement General Idea made with AIDS.

Despite the initial reaction to their AIDS work, General Idea went on to create a series of projects using their AIDS logo, producing them in diverse media, from posters to stamps to rings. They disseminated their logo to raise awareness about and combat the stigma and misinformation surrounding AIDS. Bronson stated, “Part of the hook of it for us was the fact that it involved so many issues, not only health issues, which were especially acute in the U.S., but also issues of copyright and consumerism.” The artists also continued to raise funds for AIDS charities through initiatives such as General Idea’s Putti (1993), a large-scale installation created from a commercially available seal pup–shaped hand soap placed on a beer coaster. Ten thousand of the soaps were assembled to create a gallery installation and were available for viewers to take, with the suggestion to leave a $10 donation for a local AIDS charity.

The significance of General Idea’s activism cannot be understated. At the time AIDS was a taboo topic surrounded by stigma and fear. Speaking to the climate of the era, artist and writer John Miller explained, “In 1987 especially, identifying oneself as HIV-positive differed from coming out. You could lose your job and your friends. Others still might want to quarantine you. Even obituaries skirted all mention of the disease” (Miller 2003, 291).

In the late 1980s General Idea’s AIDS work took on personal significance. One of the group’s closest friends (who helped GI in producing their artworks, Going thru the Motions (1975–76) and Test Tube (1979)) died of AIDS-related causes in 1987 in New York. The group served as primary caretakers for the last weeks of their friend’s life. Partz and Zontal were diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1989 and 1990, respectively. Both artists publicly disclosed their status and, until their deaths in 1994, General Idea continued to create poignant and engaging artwork addressing AIDS (Smith 2016).

In 1994, General Idea’s collaboration concluded with the deaths of Zontal and Partz from AIDS-related causes. Bronson continued to produce work in the wake of the loss of Zontal and Partz as well as producing works in tribute to General Idea.

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.4

In what ways is this activist project similar to General Idea’s AIDS works? How does the AIDS Memorial Quilt approach AIDS in a different way?

Violence meets vulnerability

Tom Magilery, Image of activists at the Vancouver Climate Strike Rally on October 25, 2019 at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

At the 2019 Climate Strike Rally at the Vancouver Art Gallery, thousands of demonstrators gathered to listen to environmental activists Greta Thunberg and David Suzuki, and to promote their belief that urgent action is needed to ensure the survival of the planet and the people who live on it. Many of the protesters carried cardboard placards championing their views—with slogans like”Listen to the science,” “There is no planet B”—while others brought banners or wore T-shirts emblazoned with the name (and rallying cry) of the Indigenous protest movement Idle No More. This use of banners and T-shirts within the context of a protest is not novel. Textiles—selected for their malleable, durable, and accessible properties—have long been used by activists to convey social and political messages within the public sphere. Examples abound: the abolitionist quilts stitched by anti-slavery organizations in the antebellum United States; the collection of coffin-sized blocks that raise awareness of HIV/AIDS and commemorate those lost to the disease through the AIDS Quilt (1987-); the embroidered and appliquéd banners advocating for women’s suffrage crafted and carried by members of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in the early 20th century; and the appliquéd panels (arpilleras) depicting the atrocities suffered by Chilean citizens under the reign of dictator Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s and 1980s. Artists too, have engaged with textiles as an effective medium for relaying activist ideas. Canadian artists Barbara Todd and Barbara Hunt have used fibre arts to articulate anti-war sentiments and critique militaristic policies.

Created at the tail end of the Cold War, Barbara Todd’s Security Blanket: 57 Missiles (1989)—one in a series of security blankets produced by the artist in the 1980s and 1990s—features fragments of grey, blue, brown, and black wool suiting fabric cut to echo the shape of military projectiles. These shapes are fixed to the quilt’s surface using the appliqué technique, a needlework technique commonly used in quilting which has historically been used to attach fabric pieces to a quilt that together illustrate flowers, baskets, and birds. The materials, palette, and imagery of Todd’s quilt allude to Western masculinity, aggression, technology, and the military-industrial complex, while the method of assembly draws upon techniques associated with domesticity and craft: spaces and techniques traditionally coded as feminine. By fusing these elements together, Todd creates a jarring juxtaposition that highlights the distinct and often opposing systems of value that operate simultaneously—all while positing an anti-war message. As Marni Jackson argues, by “placing these fear-filled, totemic shapes inside a larger pattern, the benign grid of the quilt, their menace is to some extent neutralized. They become mere vocabulary. . . Bombs are reduced to mere ‘decorative’ elements” (Jackson 1993).

Artist Barb Hunt similarly addresses the notion of contrast in her series Antipersonnel, which consists of a sequence of knitted and crocheted replicas of anti-personnel landmines (created to-scale) in various shades of pink yarn. Sparked by the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction, which was signed in Ottawa in 1997 and calls on signatories from the global community to end the production, storage, and use of landmines, Hunt’s work offers a meditation on human ingenuity and the many tools and weapons that have been created to ensure the destruction of human life.

In Antipersonnel, each landmine is carefully stitched in detail. Hunt has attentively articulated the mechanisms and triggers that figure into the construction of the actual objects, contrasting the mechanical and technical attributes of the landmines with the handmade qualities of knitting and crochet. The fluffy, pink forms of Hunt’s landmines, which conjure stereotypical ideas of femininity also sit uneasily with the intended function of the objects depicted. Designed to rip bodies asunder, landmines are very far removed from the notions of domesticity, comfort, and care suggested by the artwork’s materiality. However, at the same time, Antipersonnel draws upon a long association between knitting and war.

During both the First (1914-18) and Second World Wars (1939-45), Canadian women, and sometimes men, knitted sweaters, socks, scarves, hats, and bandages for service members stationed overseas, as well as for those displaced by military occupation. As the image of Dorothy McCabe, Queenie Edward, and Edith Allen knitting in a Toronto Red Cross workroom suggests, their efforts—which, in the Second World War alone, generated some 50 million garments—were often coordinated by organizations like the Red Cross, the Women’s Institute, or church groups (Canadian War Museum 2014).

In the immediate sense, the production of knitted articles was intended to fulfill an urgent need, however makers and organizers were also aware of the potential alternative readings embedded in these objects: of the connection to care and a reminder of the domestic space of the home. This feeling is alluded to in the opening pages of Monarch Knitting Company’s book, Hand Knits for Men and Women in Service: “Hand knitting is an opportunity to express, in tangible form, care and affection for those who are dear. It is an opportunity to put idle time to profitable advantage, realizing that some airman, some soldier or some sailor (often unknown to you) will be made happier by your work.” (Monarch Knitting Company 1941, 2). This fusion of violence with vulnerability, care with conflict reoccurs, not just in Hunt’s work, but also in Barbara Todd’s quilt, which melds an appliqué stockpile of armaments with the notion of a child’s security blanket.

Hunt’s and Todd’s subversive stitches are not simply political for their anti-war messaging, for their use of craft and the domestic to neutralize objects of war, but also for the very use of fibre itself—for the use of quilting and knitting, activities traditionally associated with women’s domestic craft, in a high art context. Todd’s security blankets are, for instance, displayed on the wall, not a bed, and Hunt’s knitted replicas are frequently positioned on plinths or displayed within glass cases in gallery spaces. In this way, Antipersonnel and Security Blanket: 57 Missiles continue the politicization of fibre and textiles that became pronounced in North American feminist artistic practice starting in the 1970s as makers and scholars sought to better understand women’s creative contributions historically, and to repurpose “craft” mediums for art production in the present. As art historian Elissa Auther notes, “In this context, the once negative associations of fibre with femininity and the domestic realm were recast as distinctive and culturally valuable features of an artistic heritage specific to women” (Auther 2010, 96). Since the 1970s, craft mediums have become an integral aspect of contemporary art practice; however, makers such as Hunt and Todd often still rely on the historical and seemingly unshakeable associations of fibre with the domestic, feminine, and handcrafted, to give their work its charge: to protest war—and the hierarchies of art that historically limited women’s participation in the professional sphere.

Where hope meets action: Black Lives Matter

VIEW NATALIE WOOD’S I CAN’T BREATHE HERE

Figure 11.8 Natalie Wood, I Can’t Breathe, 2019. Watercolour, acrylic and pen 47 x 32.4 cm. Private collection.

“I am particularly interested in the counter-narratives, experiences and forms of resistance, marginalized peoples convey through media and other forms of popular culture” (Wood 2021).

Trinidadian-Canadian Natalie Wood is an artist who has “waded into the sociopolitical discourse, using their creativity as a force for change” (ACI 2021). In Wood’s semi-abstract watercolour I Can’t Breathe, she depicts herself surrounded by pale floating circles, disembodied hands float before her and words flow from them reading: “This cannot be how the story ends.” The poignant title of this work—the last words spoken by Eric Garner after being put in a chokehold by a New York City Police Officer in 2014—takes on increased significance in the aftermath of George Floyd’s May 2020 murder at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. The killing of Floyd in the US sparked calls to address anti-Black racism, which reverberated across the United States, Canada, and globally, leading to #blacklivesmatter protests.

Black Lives Matter groups were, in fact, established before 2020. In 2014, artist and activist Rodney Diverlus co-founded Black Lives Matter – Toronto, and subsequently Black Lives Matter – Canada. According to their website, the group is a platform for dismantling all forms of anti-black racism, liberating blackness, supporting black healing, affirming black existence, and creating the freedom to love and self-determine, Diverlus saw the historic resurgence of BLM in the summer of 2020 as a breaking point, “Since [2014], Black artists across all disciplines have been speaking more boldly and urgently, sharing their personal experiences with the longstanding existence of anti-Black racism within Canadian arts industries and institutions.” He explains:

The legacy of anti-Black racism persists in our museums, galleries, sets, recording studios, theatres, opera, and ballet institutions; in our “classical” companies and contemporary arts spaces; in digital and new media spaces; in commercial and non-commercial spaces; in every milieu. These examples are not outliers, but the standard. These institutions, in many ways, are functioning precisely as they were created to. Weaved into the foundations of arts institutions in this country is an innate othering of the Black experience. Indeed, there has never been a time in which these institutions have included our full personhood. What we are asking for is something that has never been seen before. The task at hand will require much imagination and sacrifice by those who have historically guarded the gates of these institutions.

Black art-makers, we have done enough to educate and to teach. Much of the past year has been about identifying what is not working for us — but now, in 2021 and beyond, we have an opportunity as Black art makers and arts-related professionals to set out a collective vision for Black arts in Canada; to identify solutions made for us, by us. We have an opportunity to decentre traditionally white arts institutions and whiteness as the standard. We have an opportunity to carve out a new era of “contemporary art” that properly reflects contemporary society and those who inhabit it.

And there is no time more apt than now to imagine new possibilities. We begin this year with the arts and cultural sector in the midst of the metamorphosis of our lifetimes. Thousands of artists remain without work, practices are being adapted and morphed, and storied institutions are closing their doors or teetering on the brink of collapse. As we enter new and uncharted territories, rather than expending all our energies, talents, fixing the bricks of the fortresses that spent so long keeping us out, let us build our own. (Diverlus 2021)

Diverlus’s call for more inclusive spaces for BIPOC artists is echoed by curator Pamela Edmonds assertion, “I am no longer interested in a seat at the table. I now want to build my own table” (2019). Art historian Joana Joachim locates Edmonds at the forefront of intersectional Black feminist curatorial practices in Canada:

While large-scale museums in Canada rarely include Black artists in their collections and exhibitions, as evidenced by a 2015 study published in Canadian Art, Black women have been working in smaller institutions as artists and curators to address this exclusion (Cooley, Luo, and Morgan-Feir, 2015). Indeed, for decades, exhibitions by and for Black women in Canada have led conversations about race, representation, settler colonialism, sexuality, and class, among other subjects. As underscored by Yaniya Lee in her article “The Women Running the Show,” the late 1980s saw the advent of the very first Canadian exhibition to centre Black women and their work. Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter (1989) was also the first exhibition to be curated by Black Canadian women curators, namely Buseje Bailey and Grace Channer, members of Diasporic African Women’s Art Collective (DAWA), a non-profit network of Black Canadian women founded in 1984 (Jim 1996). This travelling exhibition ushered in the 1990s, a decade that also saw the creation of CAN:BAIA (Canadian Black Artists in Action) (1992) and the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia (BANNS) (1992). In the late 1990s, curator Pamela Edmonds began her career co-curating Skin: A Political Boundary (1998) with Meril Rasmussen, who was a student at NSCAD at the time, and who is now an instruction designer focused on social networks for education and research. Edmonds has subsequently worked in several galleries across the country, including as the Exhibitions Coordinator at A Space Gallery, Toronto, and the Director/Curator at the Art Gallery of Peterborough (Edmonds). The following decade was marked by such interventions as the exhibition Through Our Eyes (2000), curated by Edmonds and Sister Vision Press, as well as Charmaine A. Nelson’s appointment as the first Black art historian in a tenure-track position at a Canadian University in 2003. Nelson’s scholarly contributions continue to push the boundaries of Canadian art and history. (Joachim 2018, 39)

Learn more about Pamela Edmonds’s practice by watching her 2020 presentation at the conference The State of Blackness: From Production to Presentation.

Edmonds’s statement inspired a panel discussion entitled, How We Build: On Craft and Blackness, at Mount St. Vincent University (MSVU) Art Gallery in 2019. One of the speakers was artist Letitia Fraser. A graduate of the Nova Scotia School of Art and Design (NSCAD) University, Fraser was born and raised in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Her work centres around her experience as an African-Canadian woman growing up in North Preston near Halifax, home to one of the oldest and largest Black communities in Canada. Fraser’s digital portfolio includes a pencil sketch of Viola Desmond, a now-iconic image given its recent inclusion on Canada’s $10 bill.

Learn more about Viola Desmond in this video by the Canadian Museum of Human Rights:

In her resistance to segregation and her seminal role in the Canada’s civil rights movement, Desmond has often been compared to African American Rosa Parks. She was even the first historical woman of colour to be given a Heritage Minute in Historica Canada’s collection— watch it here:

Long after her death in 1965, in 2010, Desmond was pardoned by Nova Scotia’s Lieutenant Governor, Maryann Francis. Reflecting on the significance of the moment, Francis recalled, “Here I am, 64 years later—a black woman giving freedom to another black woman” (Hutchins 2014). Eight years later, the Canadian federal government unveiled an historical vertical $10 bank note featuring Desmond’s portrait with a map of her north-end Halifax neighbourhood in the background.

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.5

Art historian Gabby Moser describes the portrait of Desmond as an example of an “untaken photograph”:

a category of images introduced by the Israel-born philosopher Ariella Azoulay that describes the power photography has in shaping how we imagine history, even if no photo is ever produced. A profound optimist, Azoulay is best known for arguing that photography initiates a contract between the subject, the photographer and the viewer that compels us to act. But Azoulay also argues that untaken photos can be used to help us to picture the past differently. When events like Desmond’s spontaneous act of defiance go uncaptured, we can use the pictures taken just before, just after or at the periphery of events to imagine what was not captured (Moser 2019).

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.6

Can you think of an example of another “untaken photograph” related to activism in Canada? What would it have depicted? Why does it remain untaken?

VIEW LETITIA FRASER’S VIRTUOUS WOMAN HERE

Figure 11.10 Letitia Fraser, Virtuous Woman, 2019. Oil on canvas, 121.9 x 137.1 cm.

Returning to Letitia Fraser’s work, one of her most striking images is Virtuous Woman. Painted in 2019 and featured in her solo show at the MSVU Art Gallery it depicts her great-aunt, Liffian Downey, who helped raise her. In her unique practice she primes hand stitched quilts with rabbit skin glue and then paints her figures, with the quilt design shimmering below (Frater 2020). In an artist statement she articulates the significance of quilting:

I use, used fabrics in connection to the resourceful way my grandmother, Rosella “Mommay” Fraser, made quilts for her family. My Grandmother’s quilting, to me, was survival for my family. It was less about decoration, and more about warmth and protecting those close to you. Her quilts, as well as the African American Gee’s Bend Quilters greatly influenced my quilts. My goal is to nurture my family traditions, honouring those before me in the process (Fraser n.d.).

Another important figure leveraging quilting to tell stories for communities is the archivist, arts administrator, and activist, David Woods. He is the organizer of Nova Scotia’s first Black History Month (1984) and the founder of several arts and cultural organizations including the Cultural Awareness Youth Group of Nova Scotia (1984) and the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia (1992). In 1998 he co-curated In This Place: Black Art in Nova Scotia at NSCAD’s Anna Leonowens Gallery, a survey of art by Black artists from the past one hundred years in the province. By uncovering many overlooked artists and forgotten histories, “Woods created a sense of place, a way to teach emerging artists about the work of those who preceded them, whose legacies had largely gone undocumented and unpreserved” (Adams 2020).

VIEW DAVID WOODS’ AND LAUREL FRANCIS’S PRESTON HERE

Figure 11.11 David Woods (design) and Laurel Francis (quilting), Preston, 2007. Pieced, appliquéd, machine- and hand-stitched, hand-dyed quilt with photo transfers, 147 x 132 cm. Images on quilt courtesy the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia.

Woods’s and Francis’s work is reminiscent of artist Faith Ringgold‘s story quilts which combine imagery with text using the medium of quilting. The text in Preston alludes to the community of Preston, Nova Scotia, near Halifax, one of the most historically significant communities of Black Canadians, originally settled by Black Loyalists. The text is accompanied by historical black-and-white images which are not only appliquéd to the surface but which—as blocks—make up the fabric of the quilt itself. The confident figure in contemporary dress, similar to Fraser’s figures, appears to draw strength from the community, as one might draw water from a well.

In 2012, along with his colleagues at BANNS, Woods curated The Secret Codes: Contemporary African Nova Scotian Narrative and Picture Quilts. The exhibition featured twenty-five quilts by members of the Vale Quiltmakers Association from the New Glasgow area of Nova Scotia, and explored quilting as a vehicle for storytelling. According to the exhibition, The Secret Codes “refers to the use of quilts as a subversive medium to guide escaping slaves to the Underground Railroad” (UNB Art Centre 2014). Historians debate whether this actually occurred; however, quilting is an important art form within African American cultures. Examples include Harriet Powers’s pictorial quilts, which fuse Christian narratives with Fon symbolism and Abomey appliqué techniques, and the pieced quilts of salvaged materials crafted by Loretta Pettway, Mary Lee Bendolph, and other quilters—many the descendants of enslaved individuals—living in rural Gee’s Bend, Alabama. We might also think of the story quilts of Ringgold and the contemporary work of Sanford Biggers, who reinvents antique quilts through the application of paint or ornamentation, or by reshaping them to tell a new narrative.

Nearly ten years later, The Secret Codes was revived for a cross-country tour in 2022 with shows at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery (Charlottetown, PEI), the National Black Canadians Summit (Halifax, NS), the Quilt Canada national conference (Halifax, NS), and the Textile Museum of Canada (Toronto, ON). Filmmaker Sylvia D. Hamilton lauds Woods’s contributions to the community, noting that he has “has worked tirelessly for years to uncover early Black artists in Nova Scotia—to say, ‘Yes, we have always created art, and here are the artists’. . . . It is rare to find a visual artist who undertakes such curatorial work, and at the same time does his own work” (Parris 2018).

Hamilton herself is an important storyteller contributing to the ongoing vitality of Black communities. Her 2007 documentary, The Little Black School House, addresses the often forgotten history of Canada’s racially segregated school systems. Drawing on her own experiences in an all-Black school in Beechville, Nova Scotia, Hamilton explains her motivation for documenting this “historical amnesia,” reflecting in an interview with Brianne Howard and Sarah E.K. Smith: “It was essential for me to try to capture as many of these experiences on film as possible. So those who lived it would have some validation of what they had experienced, and so those who denied that this existed or those who had no idea, would be able to see” (Howard and Smith 2010, 64-65).

Hamilton continues:

Repurposing photographs and archival footage to use in a new manner is an important aspect of my work. Aesthetically, it was the archival footage that enabled audiences to see inside these schools, and I think this helped to concretize the memory for anyone who has attended one of these schools. This was also important for those who deny that segregated schools ever existed in Canada, as it builds a case of visual evidence. Another important part of my aesthetic strategy was the locations where I shot new footage of the old schools, often with former students returning to these locations. The old buildings became ‘‘sites of memory,’’ to use Pierre Nora’s term, and the buildings had embedded stories that I wanted to bring to light in the film. The way I structured the narration was to personify the building, to evoke those memories so that the building itself becomes a storyteller (Howard and Smith 2010, 64-45).

Watch the trailer for The Little Black School House here:

VIEW SADE ALEXIS’S ROSEMARY BROWN HERE

Figure 11.12 Sade Alexis, Rosemary Brown, 2021. Poster.

This poster was created by illustrator Sade Alexis in 2021 for Gordon House in celebration of Black History Month. In an Instagram post she shares “I had the pleasure of working with the folks at @gordonnhouse who commissioned me to make a piece about the late Rosemary Brown for BHM! This piece has been printed as posters and put up around the Gordon Neighbourhood house area!” (Alexis 2021). The poster features a stylized portrait of Brown, adorned with flowers from her homeland of Jamaica. Below the image is a quote by Brown: “When I fight for your freedom I am also fighting for my own freedom, and when I am fighting for my freedom I am fighting for my sisters’ and my brothers.”

The post goes on to share a brief biography: “Rosemary was a Black feminist, politician, writer, educator, mother and community leader. She worked tirelessly for the Black community of Vancouver as the first Black woman elected to the BC legislature. Miss Brown was responsible for bringing civil rights legislation into BC parliament, and along with this she worked to open up housing options and employment opportunities for our community here on these lands. Rosemary was, and is, an integral part of our community; she stood for the uplifting of Black people as a means of uplifting all people. As the descendant of slaves, Rosemary worked hard to make her ancestors proud, which is why this month, and every month, we honour and remember her for all she has done for us” (Alexis 2021).

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.7

The illustrator Sade Alexis shares that “her drive to draw has evolved along with her lived experience as a Black person” (Johnson 2021). For her, “Drawing and art have also always been a way for me to do something about the way I feel about Blackness. It started as a way for me to deal with the pain we experience. As I’ve grown as an artist and a Black woman, it’s been a way to cultivate my love for my Blackness and my community” (Johnson 2021).

Learn more about Alexis’s views on portraiture in this video:

Alexis’s work was recently featured in an exhibition at the Royal BC Museum. Created in partnership with the BC Black History Awareness Society, Hope Meets Action: Echoes Through the Black Continuum was curated, written, and designed by Black voices to reclaim and retell “the complicated history of stolen people on stolen land, and how the contributions of Black leaders echo across the centuries into the present” (Royal BC Museum n.d.). She recognizes the significance of representation: “It’s important for us to see depictions of ourselves and to learn our history from our own people, to go to an exhibition for us, by us,” she says. “This exhibition is also important because it’s disrupting the predominantly white Royal BC Museum. The museum has been historically a space dominated by white narratives, or narratives of BIPOC history as told to us by white people. By having this exhibition, we are forcing ourselves into this space, not to fit within it but to tear it down and build anew” (Johnson 2021).

Curator and activist Joshua Robertson, a founding member of the Hogan’s Alley Society, an organization that works to redress the displacement of Vancouver’s long-standing Black community centred around the area familiarly known as Hogan’s Alley, and to advance their social, political, economic, and cultural well-being. Joshua’s research, advocacy and consultancy focus on the centering of racialized communities in city planning, alternative economic models of inclusion, social enterprise development and redress-based urban design principles.

Watch this interview with Joshua Robertson, curator of the exhibition Hope Meets Action: Echoes Through the Black Continuum.

Robertson writes of protest and Black activism:

We as Black people have always had to fight for our rights, for our community and for our story. From the time we stepped onto Turtle Island, we have fought for the acknowledgement of our inherent right to freedom and liberation. From the start of our journey in ‘British Columbia’ we saw the mass of Black protestors at ‘Victoria’s’ docks, demanding the release of enslaved boy Charles Mitchell, held captive in 1863. Countless community organizing and direct-action efforts have been waged, such as the 1923 mobilization of Hogan’s Alley’s Black community around Fred Deal, a man whose murder conviction and sentenced to hanging for the death of a white police officer was seen as racially motivated. As the year of reckoning that was 2020 is an indication our voice will not be further silenced. To this day we grip the handle of our future tighter. We have never been mistaken about our inalienable right to liberation, and as descendants of survivors, we bear the responsibility to keep fighting.

ENGAGE with the exhibition Hope Meets Action: Echoes Through the Black Continuum here.

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.8

Select one of the images from the Hope Meets Action: Pictures From the Past exhibition. Write a detailed analysis of the image reflecting your learning from this course.

LEARNING JOURNAL 11.9

OBJECT STORIES

- John O’Brian on Robert del Tredici, Stanrock Tailings Wall, Elliot Lake, Ontario (1985)

- Mark Cheetham on Noel Harding, The Elevated Wetlands (1997-98)

- Hana Nikčević on Rebecca Belmore, Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) (2017)

References

“Abolition.” 2013. World Quilts: The American Story, International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2013. https://worldquilts.quiltstudy.org/americanstory/engagement/abolition.

Abraham, Christiana. 2021. “Toppled Monuments and Black Lives Matter: Race, Gender, and Decolonization in the Public Space. An Interview with Charmaine A. Nelson.” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice 42 (1): 1-17.

Adams, Kelsey. 2020. “Black History Decades.” Canadian Art, September 14, 2020. https://canadianart.ca/features/david-woods-black-history-decades/.

Agnes Etherington Art Centre. 2023. “Rebecca Belmore, Quote, Misquote, Fact, 2003.” https://agnes.queensu.ca/explore/collections/object/quote-misquote-fact/.

Alexis, Sade (@sade.b.alexis). 2021. “I had the pleasure of working with the folks at @gordonnhouse.” Instagram, February 25, 2021. https://www.instagram.com/p/CLuPHezhhIA/.

Allaire, Serge. 1993. “Une tradition documentaire au Québec? Quelle tradition? Quel documentaire ? [Quebec’s Documentary Tradition: What Tradition? What Documentary?].” In Le Mois de la photo 1993: Aspects de la photographie québécoise et canadienne. Translated by Vox Photo. Montreal: Vox Populi.

Angel, Sarah. 2011. “True Patriot Love.” Canadian Art, September 15, 2011. https://canadianart.ca/features/joyce_wieland/.

Art Canada Institute. 2021. “Art Activism and Politics.” ACI Newsletter, January 2021. https://www.aci-iac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Art-Canada-Institute-Newsletter_Art-Activism-and-Politics-A-Canadian-Commentary.pdf.

Auther, Elissa. 2010. String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Balzer, David. 2014. “Riel Confronts John A. Anew in Regina Performance.” Canadian Art, November 10, 2014. https://canadianart.ca/interviews/david-garneau/.

Barbara Todd. 2021. “Security Blankets.” Accessed February 19, 2023. http://www.barbaratodd.com/work/securityblankets/.

Black, Anthea, and Nicole Burisch. 2011. “Craft Hard Die Free: Radical Curatorial Strategies for Craftivism.” In Extra/ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, edited by Maria Elena Buszek, 204-21. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Canadian War Museum. 2014. “An Army of Knitters in Support of the War Effort.” Inside History, Canadian War Museum. March 10, 2014. https://www.warmuseum.ca/blog/an-army-of-knitters-in-support-of-the-war-effort/.

CBC News. 2017. “Artist Imagines ‘Man-to-man’ Chat between Riel, Macdonald on Parliament Hill.” CBC News, June 19, 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/david-garneau-parliament-hill-louis-riel-1.4167730.

Cooley, Alison, Amy Luo, and Caoimhe Morgan-Feir. 2015. “Canada’s Galleries Fall Short: The Not-so Great White North.” Canadian Art, April 21, 2015. http://canadianart. ca/features/2015/04/21/canadasgalleries-fall-short-the-not-sogreat-whitenorth.

Diverlus, Rodney. “Why Black artists need to forge our own paths–not try to fix broken institutions.” CBC News, January 15, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/arts/why-black-artists-need-to-forge-our-own-paths-not-try-to-fix-broken-institutions-1.5872571

Lee, Yaniya. 2017. “The Women Running the Show.” Canadian Art, October 2, 2017. https://canadianart.ca/features/women-running-show/.

Edmonds, Pamela. n.d. “I Curate Art.” Pamela E. Curates. Accessed March 30, 2018. http://www.pe-curates.space/about.

Ellsworth, Marcus. 2014. “Art as Activism.” Filmed November 15, 2014 at TEDxUTChattanooga, Chattanooga, TN. Video, 13:41. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLg8LMK_Ct4.

Fraser, Letitia. n.d. “Artist Statement.” Letitia Fraser. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://www.letitiafraser.com/copy-of-about-1.

Frater, Sally. 2020. “Making Throughlines.” Canadian Art, October 13, 2020. https://canadianart.ca/features/making-throughlines/.

Hollenbach, Julie. “Unpacking the Living Room.” Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, 2018. https://www.msvuart.ca/exhibition/unpacking-the-living-room/

Howard Brianne, and Sarah E.K. Smith. 2011. “The Little Black School House: Revealing the Histories of Canada’s Segregated Schools—A Conversation with Sylvia Hamilton.” Canadian Review of American Studies 41(1): 63–73.

Hunt, Barb. 2021. “Antipersonnel.” Barb Hunt. January 14, 2021. https://barbhunt.ca/2021/01/14/antipersonnel/.

Hutchins, Aaron. 2014. “‘Here I am, a black woman giving freedom to another black woman'” Mayann Francis, the first African-Nova Scotian lieutenant-governor, pardoned Viola Desmond.” MacLean’s. June 29, 2014. https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/mayann-francis-gives-viola-desmond-freedom/

International Quilt Museum. 2013. “Underground Railroad Quilts?” World Quilts: The American Story, International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2013. https://worldquilts.quiltstudy.org/americanstory/quiltsare/undergroundrailroad.

Jackson, Marni. 1993. “Uncoverings.” In Barbara Todd: Security Blankets, by Marni Jackson and Bruce Grenville. Lethbridge: Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Jim, Alice Ming Wai. 1996. “An Analysis and Documentation of the 1989 Exhibition Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 23(1/2): 71-83.

Joachim, Joana. 2018. “‘Embodiment and Subjectivity’: Intersectional Black Feminist Curatorial Practices in Canada.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 43(2): 34–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26530766.

Johnson, Gail. 2021. “Local Illustrator Works for Black Liberation through Art.” Stir: Arts & Culture Vancouver, September 16, 2021. https://www.createastir.ca/articles/hope-meets-action-sade-alexis-bc-black-history-awareness-society.

Kingston Frontenac Public Library. n.d. “Knitting for Soldiers.” Digital Kingston. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.digitalkingston.ca/wwi-in-kingston-frontenac/knitting-for-soldiers.

Lambert, Maude-Emmanuelle. 2017. “Ottawa Treaty.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 10, 2017; last edited May 15, 2017. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ottawa-treaty.

McElroy, Gil. 2020. “Barb Hunt: Antipersonnel.” International Sculpture Centre. January 28, 2015; last updated May 26, 2020. https://sculpture.org/blogpost/1860252/348635/Barb-Hunt-Antipersonnel.

Miller, John. 2003. “AIDS (1987).” In General Idea Editions 1967–1995, edited by Barbara Fischer, 291. Toronto: Blackwood Gallery; University of Toronto at Mississauga.

Monarch Knitting Company. 1941. Monarch Book No. 87: Hand Knits for Men and Women in Service. Dunnville, ON: Monarch Knitting Company; Toronto: Southam Press.

Moser, Gabrielle. 2019. “Viola Desmond Photograph—Now on $10 bill—Reminds Us That Her Brave Battle against Prejudice Went Undepicted.” Toronto Star, November 15, 2019. https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/opinion/2019/11/15/viola-desmond-photograph-now-on-10-bill-reminds-us-that-her-brave-battle-against-prejudice-went-undepicted.html.

Museum of Fine Arts. n.d. “Pictorial Quilt.” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/116166.

Museum of London. 2018. “The Hollowayettes.” Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-hollowayettes-museum-of-london/3AXB981UR9ErJg?hl=en.

National AIDS Memorial. 2021. “The History of the Quilt.” National AIDS Memorial. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt-history.

Parris, Amanda. 2018. “5 Black Canadian Artists Whose Names Should Be Known alongside the Group of Seven.” CBC Arts, January 18, 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/arts/5-black-canadian-artists-whose-names-should-be-known-alongside-the-group-of-seven-1.4493206.

Paul Petro Contemporary Art. 2021. “Exordium, Natalie Wood.” Exhibitions. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://www.paulpetro.com/exhibitions/578-Tba.

Robertson, Kirsty. 2011. “Rebellious Doilies and Subversive Stitches: Writing a Craftivist History.” In Extra/ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, edited by Maria Elena Buszek, 184-203. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Royal BC Museum. n.d. “Hope Meets Action: Echoes Through the Black Continuum: Pocket Gallery Exhibition.” https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/visit/events/calendar/event/110386/hope-meets-action-echoes-through-black-continuum

Smith, Sarah E.K. 2016. General Idea: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/general-idea/biography/.

Tousley, Nancy. 1992. “Night Watch: Barbara Todd’s Quilts Protect against the Chill of the Post-Cold War Dawn.” Canadian Art 9(4): 42-45.

Wood, Natalie. 2021. “Artist Statement.” i am Natalie Wood. Accessed February 19, 2023. http://iamnataliewood.blogspot.com/p/artist-statement.html.

An op-ed is an opinion or editorial article, typically published in a newspaper and not necessarily written by a journalist.

Often collaborative or community-based art that calls for or works toward social or political change. Most associated with the 1960s and 1970s civil rights and feminist movements, respectively.

A Toronto-based activist artist group working to destigmatize, raise awareness, and correct misinformation surrounding AIDS largely in the 1980s and early 1990s.

A widespread movement and slogan against systemic anti-Black racism, particularly in the criminal justice and law enforcement systems. Brought to international attention following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in May 2020.