ABROAD

The black and white photograph above depicts an installation view of the “Canadian Section of Fine Arts” at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924. Three large paintings by Tom Thomson (1977-1917) are featured prominently. From left to right, these paintings are: The Jack Pine (1916-7), Northern River (1914-5), and The West Wind (1916-7). Arranged below The Northern River are twelve additional panels by Thomson. Although later accounts describe the room as focused on landscape works by Thomson and his contemporaries the Group of Seven (Lawren S. Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, F.H. Varley, Frank Johnston, Franklin Carmichael and A.Y. Jackson), works by other artists, including several portraits, were also featured. One of the large artworks seen in the centre of the wall in the photograph is F.H. Varley’s Portrait of Vincent Massey (1920), and the canvas in the lower right corner (also by Varley) is John (1921), which was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada shortly after it was completed. Mirroring John on the other side of Thomson’s studies is a portrait of a young girl, possibly Emily Coonan’s Girl in a Dotted Dress (1923). In addition, interspersed between the landscapes is Regina Seiden’s Old Woman, later known as Old Immigrant Woman (1922). The various paintings and prints are hung together tightly in a style reminiscent of 19th century French salon-style exhibitions. Three small sculptures are displayed on wooden plinths at eye level. At left and in the centre are Frances Loring’s The Rod Turner (1918) and Furnace Girl (1918-19), and the larger nude male figure on the right side of the image might be The Indian by A. Phimister Proctor.

For more on the British Empire Exhibition, watch this archival footage from the Smithsonian Channel. Consider the implications of empire. How are different people from the British Empire being represented?

The “Canadian Section of Fine Arts” was one small part of the Dominion display area in the Canadian Pavilion of the British Empire Exhibition held at Wembley Park, England, from April 23rd to November 1st, 1924, and again later in 1925.

According to the exhibition catalogue:

The story of Canadian art and artists cannot be told in the forward to a catalogue. It is not at all without romance, whether it is dealing with its earliest landscape painter, Paul Kane’s wanderings among the Indians, Cornelius Kreighoff’s inimitable studies of the life of the Quebec habitant or the later rise of the Canadian art societies such as the Ontario Society of the Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy in the seventies and eighties and the establishment of the National Gallery and other art institutions.

We are living in stirring times in the literal sense of the word. The Canadian fine arts are stirring, too, for which we may be devoutly thankful, for if they were not, they would be either dead or degenerate. Canada is having the opportunity of measuring her art for the first time against that of the other British Dominions at the British Empire Exhibition and whatever may be the relative verdict, Canada will at least show that she possesses an indigenous and vigorous school of painting and sculpture, moulded by the tremendously intense character of her country and colour of her seasons (National Gallery of Canada 1924, 3).

When we consider the legacy of Canadian art abroad, the Wembley exhibition emerges as a pivotal starting point for understanding how nationalism is constructed through international exhibitions. The catalogue further hints at the aims of a regular programme of foreign exhibitions, suggesting they would “do an incalculable amount for the growth and public appreciation of art both at home and in the several dominions” (NGC, 4).

The 1924 Wembley “Canadian Section of Fine Arts” was the first of three major international exhibitions organized by the National Gallery of Canada to showcase the visual art of Canada. The following year, National Gallery of Canada Director Eric Brown and his jury revised the installation, but continued to focus on the landscapes of Thomson and the Group of Seven. In 1927, Brown was the sole curator of Éxposition d’art canadien at the Musée de Jeu de Paume, adjacent to the Louvre in Paris. This exhibition focused even more heavily on the Group of Seven’s works, and added retrospectives of Thomson’s oeuvre as well as that of the recently deceased painter James Wilson (J.W.) Morrice.

However, as these case studies demonstrate, not all exhibitions of Canadian art were resounding successes. As art historian Leslie Dawn explains, complex cultural conditions affected the international reception of the National Gallery of Canada’s attempts to “establish a unified national image and identity, different from the nascent nation’s main colonial sources” (2007, 193). According to Dawn:

The Wembley shows of 1924 and 1925 were triumphs. The British critics readily discerned and applauded the nationalist and modernist agendas within images of nature depicted as wilderness. The NGC collected the reviews and republished them in two anthologies for Canadian audiences as proof of the venture’s success (NGC, 1924). Both the reviews and the exhibitions figure prominently in the histories of Canada’s arts as validation of an emerging national identity in the 1920s.

The Parisian exhibition, however, provoked a different reception. The reviews were again collected and then translated, anticipating a third vindication (NGC, 1927). But problems arose. Bluntly put, the Paris exhibition failed. The responses were largely patronizing, if not negative. Confirmation of the works’ “nationality” and “modernity” was withheld, while the emphasis on landscapes was disparaged. The reviews were never made public. Indeed, their existence was obscured, even suppressed (McInnes, 1950, 60). And for good reason. The negative responses from the centre of modernism destabilized the foundational premise, handed down to the present, that the British reception constituted a universal recognition of the works’ uniqueness, originality, and difference, that is, its essentialized “Canadianness” (Davis 1973, 48-74).

But the variations in national receptions raise other questions. Why did the British respond positively and the French negatively? Could one infer from the British appreciation that they were already predisposed to the new Canadian painting based on their own traditions? Were, then, the Group works a recapitulation rather than a repudiation of British landscape conventions and consequently a continuity of colonial culture rather than a break with it? Conversely, did these images and issues remain unreadable to French audiences, unfamiliar with the principles and codes of the picturesque and its implementation within colonial contexts? What are the consequences of such possibilities? (193-4).

As Dawn makes clear, exhibitions are significant sites of nation-building. Art can be circulated abroad to success or failure. Art can also be exhibited domestically to international impact. This module considers how Canadian art circulates abroad, and to what end, as well as the dimensions of international representation within Canada. This module focuses on three central sites for international arts engagement: the circulation of Impressionism, the Venice Biennale, and the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67.

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.1

If you could share one work of Canadian or Indigenous art with someone unfamiliar with Canadian art, what work would it be? Why? Select an artwork and write 3 to 4 sentences about what themes and ideas it might convey about Canada.

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- describe how works of art allow us to consider international connections (e.g., Commonwealth, US-Canada, diaspora, etc.)

- discuss how Canadian artists encountered Impressionism abroad and how their engagement in modern painting styles connects to themes of intercultural and transnational hybridity, travel, exchange, and leisure

- explain Canada’s participation in the Venice Biennale in the 20th and 21st centuries

- analyze how Indigenous artists exerted sovereignty over their self-representation at Expo 67

- consider art as a venue for self-representation and the articulation of identity.

It should take you:

Installation View Text 10 min, Video 3 min

Outcomes and contents Text 5 min

Impressionism in Canada Text 25 min, Video 10 min

Canada at the Venice Biennale Text 20 min, Video 26 min

Indians of Canada Pavilion Text 15 min, Podcast 28 min, Video 18 min, Video 31 min, Video 4 min, Video 18 min, Podcast 36 min, Podcast 32 min

Learning journals 7 x 20 min = 140 min

Total: approximately 7 hours

Key works:

- Fig. 7.1 Installation view of the Canadian Section of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park in (1924)

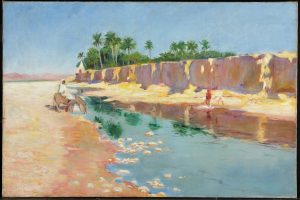

- Fig. 7.2 Maurice Cullen, An African River (1893)

- Fig. 7.3 Helen McNicoll, Chintz Sofa (c. 1912)

- Fig. 7.4 Frances M. Jones Bannerman, The Conservatory (1883)

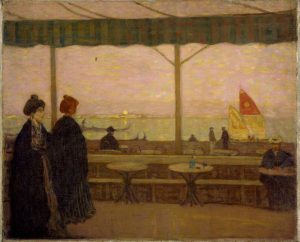

- Fig. 7.5 J.W. Morrice, Venice, Looking Out over the Lagoon (c. 1904)

- Fig. 7.6 Anne Kahane, Queue (1955)

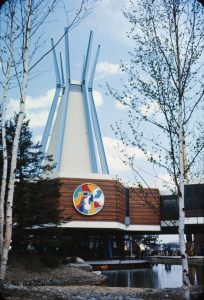

- Fig. 7.7 Indians of Canada Pavilion (1967)

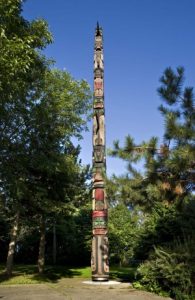

- Fig. 7.8 Henry Hunt and Tony Hunt, Totem Kwakiutl (1967)

- Fig. 7.9 Gerald Tailfeathers, Blackfoot Design (1967)

Impressionism in Canada

What, you may ask, does Canadian Impressionism look like? If only the answer was easy. A foreigner might guess at snow––a vastness of white-blanketed, frozen ground. It’s true: Canadians have created some of the most bold yet sublime effet de neige paintings, but the Impressionists with Canadian roots display an adventurous diversity of vision and experience. They travelled, collaborated, and engaged with their international artistic peers. (Burrows 2019, 7)

In the more than one hundred years since its inception, there has been a radical rethinking of the way that Impressionism has been positioned in the discipline of art history (Clark and Fowle 2020; Burns and Price 2021). For example, in the 1990s, feminist art historian Norma Broude not only reconsidered the gendering of the modern art movement, but also its international scope. More recently, the discipline of art history has sought to decolonize, globalize, and, in turn, decentre histories of modernism. Impressionism is no longer viewed through a national framework that centres it as a purely French movement. Impressionism is not one fixed style, confined to a few dozen artists; nor is it a uniquely French art form. It is now viewed as an “aesthetic toolkit” (Burns and Price 2021, 5) of techniques, subjects, meanings, and applications which artists around the world adapted and reshaped to express local experiences and places while participating in a global historical discourse.

Arguably one of the most popular artistic movements, Impressionism should instead be viewed as a plurality of impressionisms, each iteration of which might be seen as a focal point for the contacts and exchanges so central to the movement’s development. It was a truly international phenomenon, which, as the Canadian examples in this section show, connects to themes of intercultural and transnational hybridity, travel, exchange, and leisure.

Impressionism was all about artists traveling abroad and coming back, their artworks, personalities, and relationships changing the course of Canadian art forever. Art historian Brian Foss claims, “By the end of the nineteenth century. . . it was clear that Impressionism was the first major statement of modernism in Canadian art” (2010, 24). To be taken seriously as a professional artist, one had to undertake rigorous academic training in the anatomy of the human body, draw from the live model, study the great works of art from books and prints—or ideally in collections of art in Europe—and learn from other professional art teachers. This was precisely what the early art academies in Europe had been set up to institutionalize. So Canadians who wanted to be taken seriously by their peers and by art collectors in Canada often travelled abroad to study, primarily in Paris, although a few also went to London.

Many Canadian artists studied at the Académie Julian or Académie Colarossi in Paris—private schools that did not have language requirements, making them very attractive to English-speaking artists. At these training centres, artists took life-drawing classes and learned the techniques and traditions of the great European masters. Paradoxically it was at these “French system” academies that Canadian artists first became acquainted with Impressionism. The artworks in this section signal the artistic networks and transnational contexts in which Canadian artists participated. Frances Jones, Paul Peel, George A. Reid, Mary Heister Reid, William Blair Bruce, and countless others studied Impressionism and brought it back to Canada, transforming the art worlds in Toronto, Québec City, and Montreal in particular. Like their German, Swedish, or Australian contemporaries, Canadian artists were also important players in the transnational development of Impressionism.

One such artist was Maurice Cullen. The National Gallery of Canada describes his relationship with Impressionism: “Cullen depicted Canadian landscape in accordance with local terrain, light and colour. He composed his landscape paintings and pastels in keeping with European and Canadian tradition. His innovative use of luminous, Impressionist-influenced colours influenced the next generation of Canadian artists, especially the Group of Seven” (NGC 2022).

Cullen was born in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1866 and arrived in Montreal as an infant. Although he showed an early interest in art, he was obliged at the age of 14 to find employment as a clerk at the local Gault Brothers fabric company. During the evenings, after work, he studied at the fledgling Institute National des Beaux-Arts et des Sciences. After five years of part-time study, he quit his job and studied sculpture full time. He was persuaded to go to Europe, and, as soon as Cullen set his eyes upon Impressionist works, he forgot all about sculpture and turned his attention to painting. Cullen spent each summer in France in the countryside at Giverny, Poldou, Pont Aven, and Moret-sur-Loing, where the great Impressionist Alfred Sisley lived and painted.

Collector François Thiébault-Sisson advised Cullen, “At the point where you have arrived, it would be disastrous to stay away from Paris for too long a period. You need to live here several years yet—to work in the midst of the artistic movement until you are fully master of yourself and secure of success here. I will do all I can to help you sell more of your pictures from time to time” (Atanassova 253). But against the advice of his friend, who clearly believed Cullen needed to stay in Europe, the artist decided to return to Quebec in December 1895. He was a man on a mission, determined to give Canadians the opportunity to appreciate the Impressionist art he loved—and to paint the Canadian landscape in his Impressionist style. In Montreal, critics initially gave him a warm reception, although this enthusiasm did not translate into sales. In January 1896, Cullen organized an exhibition in a storefront space he rented in the Art Association building on St. Catherine Street in Montreal, where he displayed about 100 paintings, including five that he had shown in the Paris Salon. The exhibition included scenes of Moret in the Forest of Fontainebleau; of far-away panoramas of Tunisia, Algiers, and Africa; and paintings of Quebec, including the Beaupré coast. The Montreal Gazette called his works exquisite and urged all art lovers in Montreal to visit the show, but hardly any of his paintings sold. Unfortunately for Cullen, most collectors still preferred to fill their homes with the subdued colours of the “finished” canvases by the artists with the French Barbizon and Dutch Hague Schools, and they considered the pioneering artists’ works gaudy, if not crude. Another exhibition in 1897 of his paintings was also a financial flop.

For art historian Marin Young, in the history of Canadian Impressionism one particular example stands out as a “mixture of French Impressionist technique and French imperialist iconography” and an exemplar of “the assumed synthesis of local and international World Impressionism.” Read an excerpt from Young’s essay on Maurice Cullen’s An African River (1893) here:

A Canadian Impressionist is simply an Impressionist in Canada. The colored marks on an Impressionist canvas are the same, the standard argument goes, as the “impressions” received from the corner of nature in front of which the painter stood when producing the painting. (Young) This is what makes an Impressionist painting Impressionist. The stylistic means of conveying this generative logic as a significant part of a painting nonetheless emerged out of a distinctly French pictorial tradition. Indeed, most all Canadian Impressionists learned their technique in France. Non-French iconographies depicted by non-French artists could thus be assimilated to the history of French art. . . .Cullen was preparing to return to Canada after a successful six years abroad, studying and working in Paris. Having abandoned his academic training with Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alfred-Philippe Roll, he had come to embrace the plein-air painting then gripping the fancy of North American expatriate artists in France—and with some success. In early 1895, he had become the first Canadian elected as an associate member of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, and the French State had purchased one of his paintings at the Salon that year. He was surely optimistic for the public reception in his home town. No critical evaluation of Cullen’s work survives from the autumn of 1895, however, so it is all but impossible to know what the Canadian public made of such a picture. Some viewers would certainly have been able to situate the iconography within the broader artistic tendency called Orientalism. Cullen’s training with Gérome would only have confirmed such a reading. (Nochlin) The palm trees in the background and the man on a donkey clothed in a white burnous situates the “African river” more precisely in North Africa, in the mahgreb. And for those who looked closely in 1895, the artist’s inscription marking the location of his motif was still visible on the canvas: the location is Biskra, an oasis town in Algeria, a destination of growing popularity for French and other European tourists.

. . .

For a well-travelled viewer in 1895, the small structure in the background of Cullen’s painting might also have been recognizable. Situated on the edge of the embankment, to the left of the palm trees, is the tomb of a holy man, usually called a qubba or, in North Africa, a marabout (also the word for the holy man buried in the tomb) (Jenkins 10). . . . [Cullen] sought to compel the conviction that he had rendered his motif as directly as possible. Or to put it differently, the artist selected his motif carefully and sought to convey how he painted it in situ, from a precise place: seated next to the Oued Biskra, observing the play of shadow and light, of reflections on water.

As early as 1891, Cullen had been singled out as an artist who “rather inclines towards the impressionist school” (Antoniou 5). And, upon his return to Canada, he was called “an impressionist of the modern French school” (Antoniou 11). What this meant, primarily, is that the painter used broken brushstrokes and high-keyed colour. This has certainly been the quality of An African River most readily noted by viewers ever since. As Dennis Reid put it in 1990, the canvas “reveals a bold ability to describe the fraying fragmentation of forms as observed under the intense southern sunlight that suggests an affinity to the closer analysis of the Impressionists” (Reid 96). Reid alerts us here to Cullen’s use of abbreviated brushstrokes throughout the canvas. The rendering of the reflections on the water offers a good example of his sketchy facture, but the technique is also visible in the greenish and reddish tints applied on top of the ground at left. Even closer to Impressionist practice is Cullen’s treatment of the modifications of local color under the conditions of full exterior illumination. Most striking in this regard is his use of purple hues in the rendering of shadows on the riverbank cliffs at right. These formal effects, coded as the record of perceptions obtained directly en plein air was precisely what defined Impressionism for the global generation of the time.

. . .

Such “site-specific” painting became Cullen’s default mode throughout the rest of his career. After the failure to find traction at the Montreal exhibitions of 1895 and early 1896, he began to paint a series of canvases in and around Quebec City. In this campaign, he reversed his Biskra motif of sunlit sand and began painting the subject that would define his career: snow. “No Canadian painter has approached Mr. Cullen in his delineation of snow in sunshine,” wrote Margaret Laing Fairburn in 1907 (Fairbairn 12). (Young 2021, 75-94)

As Young points out, Cullen developed his own method and techniques in his home country, but his time abroad had an immense impact on his career. Back in Quebec, he sketched out-of-doors, even if it meant standing in freezing temperatures on snowshoes. He made his own small painting boards from the wood of young poplars; after drying them in heat, he plunged them in boiling linseed oil and painted them with a layer of white lead. Once he arrived at his chosen painting place, he made several sketches on these carefully prepared boards, later selecting the ones he wanted to develop into canvases, which he painted in his studio, often during the summer months. His palette mirrored the clear, high colours of the French Impressionists, but he did not break his brushstrokes to the same degree as many of his French colleagues did. He applied his colour in solid strokes so that his forms did not fragment. In one of his most famous paintings, Logging in Winter, Beaupré (1896), we can see his masterful handling of light on snow and his abilities at translating Impressionist techniques to a Canadian scene, leaving little wonder that he was seen as a major inspiration for the Group of Seven working some years later.

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.2

Advances in technology and transportation meant that by 1880 transatlantic shipping lines were established to facilitate travel to Europe. At the same time, social conventions that had governed the lives of upper-class women, such as the idea that an escort was required for any engagement outside the home, had come to seem pointless and unnecessary. The academies of Paris and London offered training that was vastly superior to that offered in Canada, especially for women. As students in these cities, young women benefited from access to the finest art galleries and museums in the world; they could join the lively communities of artists there; and the picturesque countryside was nearby for sketching trips. Florence Carlyle, Laura Muntz Lyall, and Helen McNicoll were among those who ventured to Europe to study.

Private ateliers or schools were more inclined to take female students but charged a higher rate for them than for male students, thus making attendance a privilege only for the wealthy or those lucky few who were assisted by relatives. Still, women increasingly signed up. In 1801, only twenty-eight women artists exhibited in the Paris Salon. By 1878, that number had grown to 762; by the year 1900, more than 1,000 of the exhibitors were women. Although women’s participation in art schools increased markedly in the late 19th century, they still struggled. The opportunity to study the nude model was restricted for women, as was instruction in anatomy; women students instead drew from engravings and casts of torsos. Many of the art associations allowed women members but prohibited their participation in decision-making or in upper-level positions. As a result, independent clubs surfaced for women only; while they addressed some of the crucial issues facing female artists, such groups tended to act as buffers, further insulating or marginalizing women from the general development of the visual arts. Despite the growing involvement of women in the suffrage movements of the early 19th century, women still found it difficult to participate in society as individuals.

During her lifetime, Helen McNicoll was frequently referred to as a “painter of sunshine,” a fitting description for an artist who, in her mature years, practiced the classic broken-colour Impressionism of Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley, with its preoccupation with light for its own sake. McNicoll is today best known for her Impressionistic canvases depicting children, family, and friends often posed in tranquil domestic scenes, languid afternoons at the seashore, and in intimate interior scenes. McNicoll grew up in Montreal in a family that encouraged her artistic aspirations, and their wealth and position as part of the Anglophone Protestant elite enabled her to study art in Montreal and later in England, France, and Italy. She contracted scarlet fever when she was two years old, and became deaf as a result, but it did not hold her back. McNicoll first studied with the accomplished artist William Brymner at the Art Association of Montreal. He stressed working directly from nature, and McNicoll’s work confirms that she followed his example. Her landscapes and seascapes, genre scenes, and figure works reveal her interest in capturing the subtle plays of light and shade found in nature. Brymner recognized the skill of his student and encouraged her to go to the Slade School of Art, University of London, to complete her studies, which she did in 1902.

Katarina Atanassova, Senior Curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada writes of McNicoll:

McNicoll had swiftly become a leading practitioner of Impressionism among her contemporaries. After graduating under [William] Brymner in Montreal, she went to England to expand her art studies with Algernon Talmage at St. Ives in Cornwall and absorbed certain aspects of British Impressionist painting in the country. Her Stubble Fields, c. 1912, is an example of the landscape studies for which she garnered recognition as an impressionist painter. McNicoll returned to the subject of haystacks on a number of occasions, suggesting that she was familiar with Monet’s preoccupation with the same subject, perhaps as early as 1905 when his paintings were shown at an exhibition organized by the Durand-Ruel gallery in London.

McNicoll’s immense talent in handling light—sunshine in particular—can be seen in Stubble Fields, and was very likely influenced, as Atanassova notes, by Claude Monet’s almost obsessive focus on the optical qualities of light on haystacks in his own series from the 1880s and 1890s.

It was no easy feat to be a woman artist in this period, and McNicoll’s female friendships with fellow artist Dorothea Sharp, in particular, were key to her success. As Samantha Burton writes,

Perhaps the greatest challenge for women was in being acknowledged as “professional” artists. Although women—especially women of high social standing like McNicoll—had long been encouraged to draw and paint as a demonstration of their refinement, they had difficulty in rising above the status of amateur in the eyes of art historians and curators. McNicoll does not seem to have suffered from this perception; she exhibited widely and sold her work to public institutions and private collectors. Indeed, her obituary emphasized her professionalism, saying that “Miss McNicoll was no amateur—there are few painters in the Dominion who take their art as seriously as she did.” (Saturday Night 3)

However, McNicoll’s reputation after her death seems to have been affected by this issue. When histories of Canadian art began to be written in the 1920s, McNicoll was omitted, as were most of her female colleagues. In a new nationalist narrative, wild, open landscapes were given precedence over quiet domestic scenes such as McNicoll’s Beneath the Trees, c. 1910. Not until the late twentieth century did McNicoll and her peers begin to see some recognition as practising professionals, largely due to the efforts of feminist art historians and curators who have attempted to recuperate their work. Still, research on Canadian women artists in the years before the First World War continues to lag far behind that on their female peers in France, England, and the United States (2017).

Watch Samantha Burton’s short lecture on the work of Helen McNicoll and the question: What Makes Art Canadian?

Another artist to travel widely abroad was James Wilson (J.W.) Morrice. His oeuvre is filled with scenes of Spain and Italy, North Africa, and the Caribbean. As Sandra Paikowsky notes despite his travels, he maintained a studio in Paris “with ready access to galleries, exhibitions, newspapers, art, and illustrated magazines, and conversations with his wide circle of artistic and literary friends. Morrice was a first-hand witness to the evolution of the original Impressionists” (2019, 73).

In the essay “James Wilson Morrice: Venice at the Golden Hour,” Dennis Reid describes Morrice’s relationship with the city of Venice as follows:

James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924) was born and raised in Montreal, and although he studied law in Toronto and was called to the Ontario bar in 1889, he was by then already exhibiting professionally as an artist. In 1890 he left Canada to study painting in London, and in the fall of 1891 he moved to Paris and enrolled in the Académie Julian, where he became involved with other English-speaking painters who introduced him to painting locales around France and drew him into the Anglo-American circle of artists and writers that had gathered around the famous American artist James McNeill Whistler.

That connection may have piqued his initial interest in Venice, which was a favourite subject of Whistler’s. Morrice first visited Venice in 1894. He returned for a longer stay in 1897 and for a visit of some duration in the summer of 1901, then again in 1902, 1904 and 1907. He began exhibiting Venetian work in 1902, canvases painted in his Paris studio based on oil sketches and drawings. He participated in the Venice Biennale twice—in 1903 and 1905—but showed French subjects.

Morrice exhibited regularly in the Paris Salon and in major exhibitions in London and Canada, and his Venetian work came just when he was beginning to receive regular praise from international critics. One of the most memorable of his Venetian canvases, however, seems not to have been shown in a catalogued exhibition during his lifetime, and remained in his hands until his death.

Decades later in 1903, when Morrice’s work was selected by the National Gallery to represent the country at the Venice Biennale, he was positioned as a key point of origin for the European influence on Canadian art:

He is probably the best painter Canada has yet produced, and his position is enhanced by the fact of his being the first to introduce Canada to modern movements in art. Before him, we were an artistic backwater into which European movements arrived a quarter of a century late; after him we began to swim in the full stream of western art. In his own time Morrice could not have been what he was by remaining in Canada. He was born in Montreal and, after a short period spent studying law in Toronto, he became an expatriate in Paris…Later he became the friend of some of the most important painters of his time, notably the Fauves. (NGCA, NGCF, Canadian Exhibitions – Foreign, Venice Biennale, 1958, Hubbard, “Canada,” 1958, 159)

Morrice was the first Canadian artist to exhibit at the Venice Biennale, first showing in 1903 and then again in 1905 when On the Cliff, Normandy (c. 1902) and Regatta at San Malo (c. 1905) were hung in Room V of the Central Pavilion, housing Italian and International works in eleven different galleries (Paikowsky 1999, 131).

Canada at the Venice Biennale

The promotion abroad of a notion of Canada is not a luxury but an obligation, and a more generous policy in this field would have important results, both concrete and intangible. . . . Exchanges with other nations in the field of the arts and letters will help us to make our reasonable contribution to civilized life. (“The Projection of Canada Abroad” Massey Report, Section V)

Although Morrice was the first Canadian to exhibit in the 5th and 6th Biennales, he participated as an individually invited artist, not as a national representative. As a country, Canada did not have formal representation with a national pavilion until 1952. This debut appearance, Sandra Paikowsky notes, “positioned Canada on the world stage and marked the first significant ‘projection’ abroad” of the country’s aesthetic identity following the Second World War (1999, 131).

According to Paikowsky,

The groundwork for Canada’s participation in the 1952 Venice Biennale was being prepared at home. In the political arena, Canada’s impressive presence on the international stage during World War II and her subsequent record as an aggressive advocate of post-war collective security pacts brought her new recognition as a middle power… prior to Canada’s first participation at the Biennale in 1952, her cultural presence in Italy was rather limited. The Information Division of the Department of External Affairs had expressed an interest in art exhibitions in 1949, although it was decided that education was a more pressing matter. A year later External Affairs attempted to involve the National Gallery, or more accurately its Design Centre, in exhibitions of “Decorative and Industrial Modern Art and Modern Architecture in Milan,” but this took several years to come about. The two agencies did cooperate in 1950 in writing an article entitled “Canadian Art Abroad,” published in the government’s magazine External Affairs. However, the Department noted in an internal memorandum that the relations with the National Gallery were “not good.” Meanwhile, the National Gallery lent Renaissance works from its permanent collection to a few Italian exhibitions and it was involved in the 1949 presentation of engravings and gouaches by Roloff Beny and gouaches by Robert LaPalme in Rome. It also assisted in “Il Mostra Internationale di Bianco e Nero” held in Lugano shortly before the opening of the 1952 Venice Biennale, which included work by Albert Dumouchel, Lilian Freiman, Jack Nichols and Alfred Pellan. This weak record of Canadian cultural activities in Europe, however, would receive attention with the establishment of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences.

The import of the 1949-1951 Massey Commission has received lengthy examination in the discourse on Canadian cultural nationalism. (1999, 134-5)

Canada’s first national representation in 1952 included selected works by Emily Carr, David Milne, Goodridge Roberts, and Alfred Pellan. A retrospective of J.W. Morrice’s contributions to Canadian art was mounted in 1958, juxtaposing his oeuvre with the next generation of artists from Montreal: painter Jacques de Tonnancour, sculptor Anne Kahane, and printmaker Jack Nichols.

See footage of the 1958 Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in Katerine Giguère’s 2020 documentary Open Sky, Portrait of a Pavilion in Venice.

In her thesis on Canada’s participation at the Venice Biennale in the 1950s, art historian Elizabeth Diggon comments on the exhibition in the newly constructed space:

Given the pavilion’s symbolic significance to the NGC as Canada’s “coming of age” within postwar biennial culture, the NGC required an actual exhibition to accompany the pavilion. The NGC opted to present a Morrice retrospective (as the major component of the exhibition, along with works by contemporary artists Jacques de Tonnancour, Anne Kahane and Jack Nichols. Morrice had exhibited extensively in France and Britain and maintained an excellent reputation abroad. Given his past successes in Europe, Morrice was an undeniably safe choice. Additionally, his lengthy stays in France led to working relationships with major French painters including Henri Matisse; relationships that were credited as being highly influential and beneficial for Morrice’s work.

Of the included artists, Morrice is undeniably the focal point. However it is important to note that the new pavilion is discussed first. Jacques de Tonnancour, a Quebecois landscape painter, is given a paragraph later in the catalogue, which discusses the evolution of his painting style, with particular emphasis placed on his work, which was influenced by the School of Paris. Anne Kahane and Jack Nichols––a sculptor and painter/printmaker, respectively––the other two contemporary artists included in the Biennale, are given almost incidental mention in the catalogue entry’s final paragraph.

. . .Nichols, Kahane and, to a lesser extent, Tonnancour are treated as ancillary additions to the Morrice retrospective. Given the characterization of Morrice as the entry point for European influence into Canadian art, they are effectively situated as three of many Canadian artists who were indirectly influenced by Morrice. These priorities are emphasized by the number of works chosen for each artist: twenty-two from Morrice, eleven from Tonnancour, seven from Nichols, and five from Kahane (2012, 72).

Born in 1917, Jacques de Tonnancour studied at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal in the late 1930s, but left to pursue more innovative approaches to painting, later joining the Contemporary Arts Society of Montreal in 1942. The National Gallery of Canada describes his travels abroad, noting:

In 1945, de Tonnancour was awarded a grant by the government of Brazil and settled in Rio de Janeiro for sixteen months. He created a number of major canvases inspired by his luxurious and exotic environment there (The Sugar Loaf, Rio de Janeiro, 1946). Upon his return to Canada, de Tonnancour became disenchanted with the more familiar landscape of his homeland and turned to still life and studies of people, strongly influenced by Picasso and Matisse, such as Seated Girl (II) (1953). In the mid-1950s, travels in the Laurentians, northern Ontario and Vancouver revived his passion for the Canadian countryside and its vast spaces. His progression toward representing these led him to develop, starting in 1959, his “squeegee” technique. Abstraction followed soon after, as he explored mixed techniques and “hieroglyphics” in his later works, such as Epitaph (1968). His participation in conferences in South America during the 1980s renewed his interest in entomology and he abandoned painting in order to devote himself to collecting and photographing insects. (NGC 2022)

Figure 7.6 Anne Kahane, Queue, 1955. Wood, 63.5 x 122 x 24 cm. National Gallery of Canada.

Similarly, Anne Kahane became known internationally for her sculpture:

Born in Vienna in 1924, Anne Kahane immigrated to Montreal with her parents when she was two. After attending the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, she studied at the Cooper Union School in New York City from 1945 to 1947. In 1953, Kahane won a prize at the first International Sculpture Competition sponsored by the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. In 1958, she represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. She quickly gained prominence as an artist, with exhibitions at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, among others.

From 1950 until the 1970s, Kahane favoured wood as a medium. During the period, she created several public artworks, including one for Montreal’s Place des Arts. By 1978, she had switched to sheets of aluminum, a material that gave her a flexibility impossible to obtain with wood. Although the brass sculpture in the Town’s collection was made long before the late 1970s, it departs from the esthetic criteria in fashion at the time by stepping away from abstraction and using construction and assembly as opposed to the more traditional techniques of modelling and direct carving (Ville de Montreal 2022).

To learn more about the other artist included in the 1958 exhibition at the Canada Pavilion, watch Jack Nichols speak about his work:

Deanna Schmidt provides this thoughtful history of Canada’s participation at the Venice Biennale:

As the name suggests, the La Biennale di Venezia / Venice Art Biennale takes place in Venice, Italy, every two years and is widely considered the most significant global contemporary art exposition. Often referred to as the “Olympics of the Art World,” the Biennale brings together almost a hundred countries that collectively showcase the work of a formidable group of artists chosen to represent their home nations.

A consistent theme of nationhood has been a part of the Biennale since its inception, positioning artists and their artwork within larger political contexts and narratives. The first iteration opened on April 30, 1895, at a newly constructed pavilion in the public Giardini della Biennale / Biennale Gardens of Castello, the largest of the sestieri (districts) of the city. The genesis for a Venetian-organized contemporary art festival grew out of the success of the 1887 Esposizione Artistica Nazionale / National Art Exposition hosted in the city and is now attributed to Riccardo Selvatico, then mayor of Venice, Antonio Fradeletto, member of city council, and philosopher Giovanni Bordiga. “The international emphasis was deliberate and productive, reflecting the ambition to make the exhibition an international event,” observes Margaret Plant, and, “in this way it diverged significantly from previous national expositions, although Italian and Venetian art were well represented.” In that first year, 285 artists (with a total of 516 works) from France, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands and other countries participated.

Today, the main venue of the Biennale is located at the eastern tip of the island of Venice, occupying one of the city’s few green spaces. These Giardini are a product of major urban renovations made under Emperor Napoleon I after the fall of the Venetian Republic at the hands of the French in 1797. Since then, however, the site has gradually been adopted and transformed into a psuedo-international village with many of the participating nations constructing highly individualized permanent architectural pavilions to house their country’s biannual offering, affording each nation (who has the space and resources) independence to determine its representation.

Canada’s formal representation at the Biennale began in 1952 with an exhibition of paintings by Alfred Pellan, Goodridge Roberts, Emily Carr and David Milne mounted in the Canadian room in the Padiglione Italia / Italian Pavilion (later renamed Padiglione Centrale / Central Pavilion). Within the Central Pavilion countries were organized alphabetically, with Cuba and Brazil as Canada’s neighbours, providing an early example of how the dominance of national participation shapes visitor experience. The significance of such inclusion at the Biennale to Canada was noted by Donald Buchanan, then Director of the Industrial Design Division of the National Gallery of Canada, in the 1952 summer issue of Canadian Art. “Canada now takes its place with most of the other nations of the free world in this assembly of the arts,” he noted. Only six years later, Canada inaugurated its own permanent pavilion. (2019)

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.3

Find the website for the upcoming Venice Biennale. When is the next edition? What is the curatorial approach to the event? What types of works and artistic approaches are being emphasized? Has the Canadian representative been announced?

Artists who have represented Canada at the Venice Biennale:

| 1952 | Emily Carr, David Milne, Goodridge Roberts, Alfred Pellan |

| 1954 | BC Binning, Paul-Emile Borduas, Jean-Paul Riopelle |

| 1956 | Jack Shadbolt, Louis Archambault, Harold Town |

| 1958 | James Wilson Morrice, Jacques de Tonnancour, Anne Kahane, Jack Nichols |

| 1960 | Edmund Alleyn, Graham Coughtry, JeanPaul Lemieux, Frances Loring, Albert Dumouchel |

| 1962 | Jean-Paul Riopelle |

| 1964 | Harold Town, Elza Mayhew |

| 1966 | Alex Coville, Yves Gaucher, Sorel Etrog |

| 1968 | Ulysse Comtois, Guido Molinari |

| 1970 | Michael Snow |

| 1972 | Gershon Iskowitz, Walter Redinger |

| 1976 | Greg Curnoe |

| 1978 | Ron Martin, Henry Saxe |

| 1980 | Collin Campbell, Pierre Falardeau & Julien Poulin, General Idea, Tom Sherman, Lisa Steele |

| 1982 | Paterson Ewen |

| 1984 | Ian Carr-Harris, Liz Magor |

| 1986 | Melvin Charney, Krzysztof Wodiczko |

| 1988 | Roland Brener, Michel Goulet |

| 1990 | Genevieve Cadieux |

| 1993 | Robin Collyer |

| 1995 | Edward Poitras |

| 1997 | Rodney Graham |

| 1999 | Tom Dean |

| 2001 | Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller |

| 2003 | Jana Sterbak |

| 2005 | Rebecca Belmore |

| 2007 | David Altmejd |

| 2009 | Mark Lewis |

| 2011 | Steven Shearer |

| 2013 | Shary Boyle |

| 2015 | BGL |

| 2017 | Geoffrey Farmer |

| 2019 | Isuma |

| 2022 | Stan Douglas |

| 2024 | Kapwani Kiwanga |

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.4

Deanna Schmidt describes recent participation at the Biennale by Canadian artists:

In recent years, there has also been an increasing acknowledgement of the politics and privilege tied to exhibiting at the Biennale. Framing her solo exhibition Music for Silence at the 55th Biennale in 2013, Toronto-based Shary Boyle presented a silent, 35 mm film featuring a deaf woman signing the poem Silent Dedication (2013), which Boyle also read aloud at the opening. Serving as a direct reminder to those in attendance of their position, the poem asked audiences to consider who was not present at the Biennale and why that may be.

In turn, Geoffrey Farmer’s A way out of the mirror in 2017 coincided with the country’s sesquicentennial celebrations, inhabiting the Pavilion mid-renovation with material and metaphoric rubble from 150 years of national construction, including rebar from the Peter Pitseolak School in Kinngait (Cape Dorset), NU, that burned down in 2015.

Still, whether lauded or loathed, the Canada Pavilion remains material scaffold for larger concepts of nation-building—political, economic and artistic—as they continue to transform. As the collective Isuma prepares to release their newest film One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019) and live streaming project Silakut Live inside the Pavilion that, together, explore the damages of this colonial project, perhaps there is no better home.

Isuma the artist collective from Igloolik, Nunavut represented Canada at the 58th Venice Biennale in May 2019. The NGC described their methods noting, “Using the internet as a tool, Isuma uses this technology as a vessel for Inuit knowledge and engages with the core value of being accessible. They encourage as many people as possible to have access to their video work. This includes their website which is used to pass on this information, that Inuit find important along with many other people living on our planet. This year, with a grounding in Venice, two methods of communication and storytelling are presented.” (2019)

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.5

Go to Isuma TV online and explore the platform. Take note of the different ways you can explore the videos on this website. Identify a video you are interested in and watch it. Please answer the following questions about the video once you have viewed it:

- How did you make your video selection? For example, did you search by topic or select a recommended video?

- Describe the video work you watched. Is there a narrative? What happens?

- Think about the aesthetic strategies employed in creating the video. What formal choices did the creators make? For instance, you might describe the types of shots used, the lighting and colour, etc.

Considering Isuma’s representation, Lori Blondeau notes: “When Edward [Poitras] and Rebecca [Belmore] showed there it was such a huge thing, I remember, and now Isuma is there too. I think it is important to recognize them like this because of the great work they do. Not only in what they produce, but also the way they involve the whole community in their work” (Igloliorte 2019).

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.6

Imagine you are invited to program the Canada Pavilion at the next Venice Biennale. What contemporary artist (or artists) would you choose to exhibit? Consider the field of Canadian contemporary art, the history of Canadian programming at the Venice Biennale (both in the pavilion and off site), and also the audiences––curators, artists, museum workers, collectors, donors, diplomats, students, tourists, the general public, and many others––who will see your exhibition.

- Explain your choice of artist with reference to their practice, career stage, and suitability for this opportunity.

- Discuss two works by the artist you would like to include in the pavilion. Be sure to provide a visual analysis of the works! Include at least two figures in your assignment.

- Justify your choices for the pavilion in relation to the context of Canadian representation at the biennale.

Discuss how the work of the artist(s) you select will connect with diverse international audiences. What messages do you hope to convey, and why?

Indians of Canada Pavilions at Expo 67

Historically, international cultural events have been an important site for issues of representation. These events occur not only abroad in places like Venice, but also in domestic contexts intended for international audiences.

As Magdalena Milosz argues, Expo 67 was an important site for Indigenous representation. The Indians of Canada Pavilion was the first large-scale exhibition of Indigenous art organized by Indigenous people in Canada. As Milosz writes: “Expo 67 in Montreal was different in that First Nations took control of their own representation on the world stage. Artists created contemporary works that defied stereotypes while the exhibits inside the pavilion presented a critical—and subversive—narrative of First Nations-state relations. Yet the federal government remained significantly involved in the pavilion’s creation, notably through the design of its architecture. The pavilion can thus be read as a contact zone between Indigenous and settler-colonial representations, illuminating First Nations’ struggles for sovereignty at the moment of Canada’s centennial” (Milosz 2021).

Learn more about the connections between settler colonialism and J.W. Francis’ architecture, in this article by architectural historian Magdalena Milosz.

The Indians of Canada Pavilion was designed by settler architect J.W. Francis. Francis was the architect for Indian Affairs; in this capacity he also designed projects including residential schools and model homes for Indigenous communities across Canada. As Milosz notes, the pavilion “become a complex site of negotiation as a committee of Indigenous representatives struggled to reclaim their nations’ representation on the world stage” (2021).

Check out Magdalena Milosz’s object story, which examines the design process for the Indians of Canada Pavilion and assesses the building itself. Milosz employs settler-colonial theory as a lens to discuss the tensions and contradictions of using a government-designed pavilion to represent Indigenous communities in an international exposition. Further, Milosz speaks to the ways in which Indigenous artists and exhibition designers reclaimed the pavilion’s narrative to tell a more critical story of Indigenous relationships with the settler state. She argues that the pavilion is “a highly visible example of one of many twentieth-century architectures that constituted ‘sites of encounter’ between Indigenous peoples and the settler state of Canada. The pavilion allows us to question the notion of architecture as a neutral, unchanging backdrop for politics and examine architecture itself as political, and in particular the forms of power and resistance registered at this particular site.”

Outside the pavilion was Henry Hunt and Tony Hunt’s Totem Kwakiutl, created in 1967. Still standing on Île Notre-Dame, as the Art Public of Ville de Montreal website describes, the pole differs from poles traditionally erected:

Sculpted from a red-cedar trunk, it comprises six mythological figures placed vertically: Gwa’wis (Sea Crow), Gila (Grizzly Bear and Salmon), Sisiutl (Two-headed Snake), Makhinukhw (Killer Whale with Seal in Its Mouth), Tsawi (Beaver), and Numas (Old Man). Some sections of the pole are painted red, green, or black, whereas other sections have been left unpainted.

The Kwakiutl totem pole differs from poles traditionally erected on reserves in that it was a commission from outside of Aboriginal culture for the 1967 World Fair. It was produced in relation to the aesthetic code in force on the Pacific Northwest coast. The six mythological figures portrayed are emblems of a number of KwaKwaka’wakw clans and do not draw on a particular family line, in order to illustrate that all of these clans are acting together.

The artwork was an integral part of the concept for the Canadian Indians pavilion at the 1967 World Fair. Today, it is the only remaining vestige of the pavilion, which recognized the contribution of Indigenous nations to Canadian society and the unique nature of their cultures. At the inauguration of the artwork, on 10 February 1967, a ceremony in the Kwakiutl tradition complemented the official speeches.

Born in Fort Rupert, British Columbia, Henry Hunt (1923-1985) was known for his carved sculptures and research on all forms of art of Pacific Coast Indigenous cultures. Between 1962 and 1974, he was chief sculptor at the Royal British Columbia Museum, where his son, Tony, served as his assistant. During their careers, the two men created, together or individually, numerous totem poles that are on display all over the world. For example, in 1970 they jointly produced a totem pole for the Osaka World Fair.

The Hunts were trained through the passing of knowledge from generation to generation, reaching back to Charlie James, a renowned late-nineteenth-century artist known for having created a style specific to the Kwakiutl of Fort Rupert. His son-in-law, Mungo Martin, was exceptionally talented and one of the great master sculptors of the Pacific coast. He transmitted his knowledge, technique, and art to his son-in-law, Henry Hunt, and his grandson, Tony. Tony Hunt was also the founder of Arts of the Raven Gallery, an organization devoted to teaching young Aboriginal sculptors. (Ville de Montreal 2022)

Watch this archival video about carvers Mungo Martin and Henry from 1963, a few years before Expo. Please note that it uses terminology of the time, and should be viewed as a document of the 1960s.

In this more recent video, David Knox and Mervyn Hunt describe the restoration of a pole carved in the 1960s.

Writing about Norval Morrisseau, art historian Carmen Robertson notes: “In 1967 Indigenous artists were commissioned to create the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67, a moment now considered pivotal in acknowledging activism and awareness of Indigenous issues in Canada. Morrisseau was part of a group called the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., which was established by Odawa artist Daphne Odjig (1919–2016) in Winnipeg in 1973 and labelled the Indian Group of Seven by the press.” She explains that Morrisseau left the project after his mural design depicting bear cubs nursing from Mother Earth was deemed too controversial by government officials.

Watch Michel Régnier’s National Film Board of Canada documentary, Indian Memento (1967), which takes a first-hand look at the Indians of Canada Pavilion:

Blackfoot artist Gerald Tailfeathers created the exterior mural for the Indians of Canada Pavilion. Tailfeathers’ mural, art practice, and political life in the 1960s have been largely overlooked in Canadian art history.

LEARNING JOURNAL 7.7

What artists were mentioned in “Canadian artists at Expo 67”? Reflect critically on what work in this period was seen as significant to national representation: Which artists were shown? What type of work?

OBJECT STORIES

- Samantha Burton on Frances Jones (Bannerman), In the Conservatory (1883)

- Magdalena Milosz on Joseph W. Francis (architect), Indians of Canada Pavilion (1967)

References

“A Loss to Canadian Art.” 1915. Saturday Night 28, July 10, 1915.

Antoniou, Sylvie. 1982. Maurice Cullen. Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Atanassova, Katerina, et al. 2019. Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880-1930. Ottawa; Stuttgart: National Gallery of Canada; Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

Broude, Norma, ed. 1990. World Impressionism: The International Movement, 1860–1920. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Buchanan, D. W. 1958. “Canada Builds a Pavilion at Venice; with French Summary.” Canadian Art 15 (January): 29-75.

Burns, Emily C., and Alice M. Rudy Price. 2021. Mapping Impressionist Painting in Transnational Contexts. New York and London: Routledge.

Burrows, Malcolm. 2019. “A Message from the Exhibition Patron.” In Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880-1930, Katerina Atanassova et. al. Ottawa; Stuttgart: National Gallery of Canada; Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

Burton, Samantha. 2017. Helen McNicoll: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/helen-mcnicoll/credits/.

Canada, and Vincent Massey. 1951. Report: Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, 1949-1951. Ottawa: King’s Printer.

Clark, Alexis, and Frances Fowle, eds. 2020. Globalizing Impressionism: Reception, Translation, and Transnationalism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dawn, Leslie. 2007. “The Britishness of Canadian Art.” In Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art, edited by John O’Brian and Peter White. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Davis, Ann. 1973. “The Wembley Controversy in Canadian Art.” Canadian Historical Review 54 (March): 48-74.

Diggon, Elizabeth. 2012. “The Politics of Cultural Power: Canadian Participation at the Venice and San Paulo Biennials, 1951-1958. MA Thesis, Queen’s University.

Fairbairn, Margaret Laing. 1907. “A Milestone in Canadian Art.” The Canadian Courier 1, April 13, 1907.

Foss, Brian. 2010. “Into the New Century: Painting c. 1890-1914.” In The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century, edited by Brian Foss, Anne Whitelaw and Sandra Paikowsky, 17-37. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Igloliorte, Heather. 2019. “Indigenous Art on a Global Stage.” Inuit Art Quarterly, May 10, 2019. https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/vantage-point-indigenous-art-on-a-global-stage.

McInnes, Graham. 1950. Canadian Art. Toronto: Macmillan.

National Gallery of Canada. 2022. “Maurice Cullen.” https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artist/maurice-cullen.

National Gallery of Canada. 2022. “Jacques de Tonnancour.” https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artist/jacques-de-tonnancour.

National Gallery of Canada Archives, National Gallery of Canada Fonds. 1958. Canadian Exhibitions—Foreign, Venice Biennale, 1958. Hubbard, “Canada,” 159.

Jenkins Jr., Everett. 2000. The Muslim Diaspora: A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Vol. 2: 1500–1799. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Milosz, Magdalena. 2021. “Settler-Colonial Modern.” Canadian Architect, September 1, 2021. https://www.canadianarchitect.com/settler-colonial-modern/.

Nochlin, Linda. “The Imaginary Orient.” Art in America 71, no. 5 (May 1983): 118–31, 186, 189, 191; reprinted in Nochlin, The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society, 33-59. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

Paikowsky, Sandra. “Constructing an Identity. The 1952 XXVI Biennale di Venezia and ‘The Projection of Canada Abroad.'” Journal of Canadian Art History 20 no. 1/2 (1999): 130-81.

Reid, Dennis. 1990. “Canadian Impressionism.” In World Impressionism: The International Movement, 1860–1920, edited by Norma Broude. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Reid, Dennis. 2013. “James Wilson Morrice: Venice at the Golden Hour.” Canadian Art, September 11, 2013. https://canadianart.ca/features/james-wilson-morrice-venice/.

Schmidt, Deanna. 2019. “The Canadian Pavilion in Venice.” Inuit Art Quarterly, May 3, 2019. https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/vantage-point-the-canada-pavilion-in-venice.

Young, Marnin. 2021. “Impressionism and Criticism.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Impressionism, edited by André Dombrowski, 11-26. Oxford: Wiley.

Ville de Montreal. 2022. “Anne Kahane.” Art Public Montreal. https://artpublicmontreal.ca/en/artiste/kahane-anne/.

Ville de Montreal. 2022. “Henry Hunt, Tony Hunt, Totem Kwakiutl 1967.” Art Public Montreal. https://artpublic.ville.montreal.qc.ca/en/oeuvre/totem-kwakiutl/.