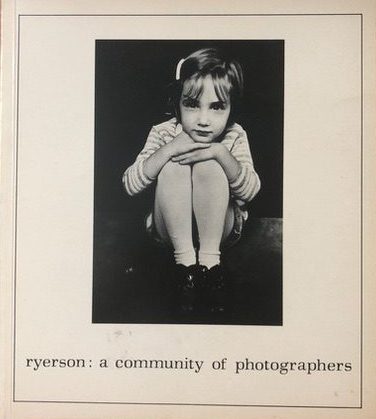

Ryerson: A Community of Photographers (1974)

by Tal-Or Ben-Choreen

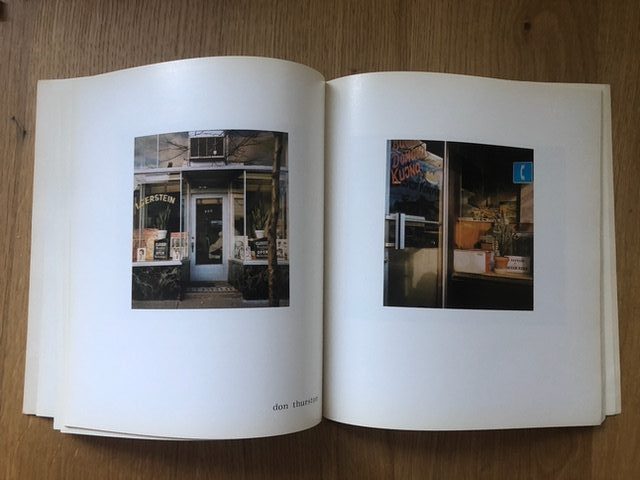

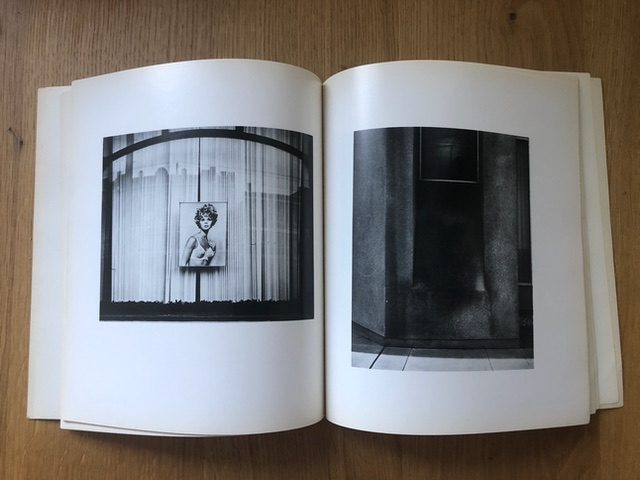

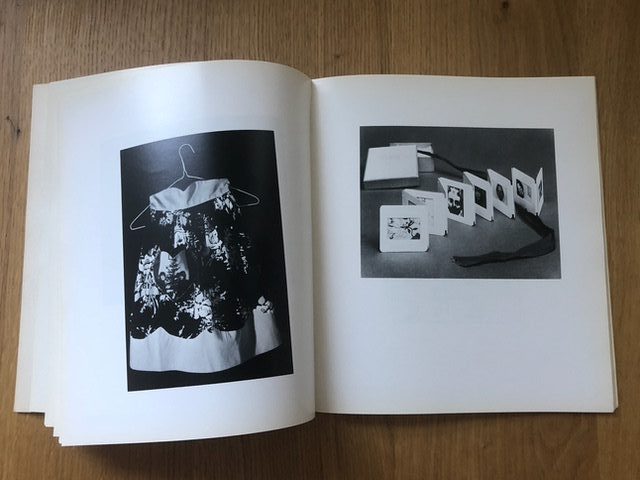

Ryerson: A Community of Photographers is a 64-page catalogue published in 1974 to accompany an exhibition of the same name held at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) and organised by Image Arts students at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute [currently Toronto Metropolitan University], in Toronto, Ontario. The catalogue opens with a brief introduction by faculty member Don [Donald Arthur] Dickinson (1942-2007) that describes the creative atmosphere at the school. Three reproduced works from each of 16 participating photographers are included, each image centered on a single page. These works vary greatly, showcasing colour photography, ‘straight’ and ‘documentary’ photography, mixed media, collage pieces, and sculptural work. This catalogue demonstrates the active role students played in the emergence of photography as a creative discipline.

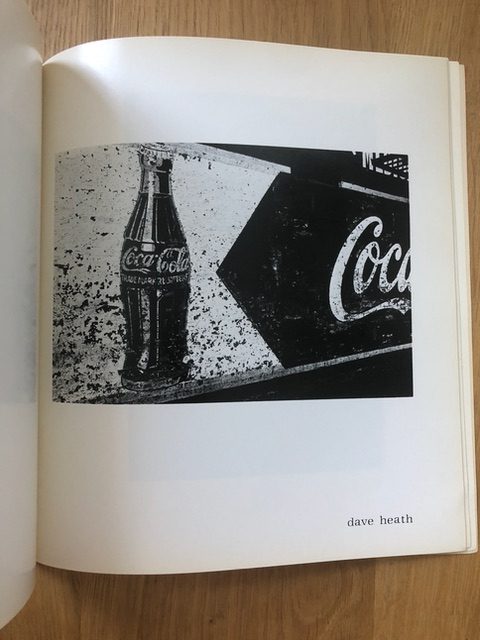

The 16 photography students are Ellie Forrest, Marci Colthorpe, Bill Morgan, Don Thurston, Clare Schreiber, Bill Grigsby, Eleanor Lazare, Michael Rafelson, Chris Clark, Edwin Gailits, Paul Douglass, Roger Schip, and John Bloom. Faculty members include Phil Bergerson, Bill Scanlon, and David Heath.

Ryerson

In 1948, Ryerson [currently Toronto Metropolitan University] opened its doors in Toronto, Ontario as an alternative to the traditional apprenticeship school model, uses hands-on skill specific training typically guided by an expert in the field. The new institution was meant to quickly and efficiently prepare its student body to respond to the growing needs of the post-World War II economy. At first, photography education at the school was largely focused on technical skills, and students were trained to become commercial studio photographers or lab technicians for Canada’s booming photography industries and companies, including the Canadian Kodak Co., a branch of the Eastman Kodak Company.

In 1970, the Photographic Arts Department was established to house the photographic art diploma. This new department was part of the larger Applied Arts Division which included departments such as Library Arts, Journalism, Interior Design, Radio and Television Arts, Business and Technical Communications, and Home Economics. The 1970-1971 academic year also introduced several diploma options for the study of photography. Under the Photographic Arts diploma students could specialise in still photography studies, motion picture studies, or media studies. In addition, a new diploma was made available titled Photographic Arts Advanced. These programs were designed to teach the use of photography as a tool of creative expression, a central aspect of the emerging ‘creative photography’ field. This shift in the conceptualization of the medium mirrored a larger educational shift led largely by American universities and colleges.

Creative Photography in Toronto

Toronto’s metropolitan centre, its connection to Kodak as a major manufacturing hub, and its close proximity to Rochester, made it a hotbed for photography. Kodak’s manufacturing facilities operated in Toronto between 1899-2005 and at Kodak’s peak the facilities employed some 3,000 people. Kodak sponsored photography activities in the GTA. Over the course of the 1960s, photographers in the United States and Canada sought to establish themselves as artists. As there were few venues for the serious treatment of photography as a creative medium, these photographers relied upon each other to form loose communities and informal support systems, both locally and transnationally. In the Toronto region, local institutions of higher education such as Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, Sheridan College of Applied Arts and Technology, York University, and the Ontario College of Art developed programs that educated generations photographers. Prior to the 1970s, photography was not typically displayed in commercial galleries, although few exceptions could be found, such as Isaac’s Gallery. The lack of institutional support for photography as an artistic approach meant that photographers had to create spaces and communities to sustain and nurture their creative output. In 1969, the Baldwin Street Gallery (BSG) opened as the first independent photography gallery in Toronto, Canada. As Americans immigrated to Canada to avoid the draft and as photography graduates emerged from different programs in Toronto, they created spaces to display and discuss photography. These communities would form vital artist-run centres that still sustain artists today such as the Toronto Photographers Workshop (TPW), Gallery 44, and the Art Gallery at Harbourfront (the Power Plant). Artists-run centres activities and commercial galleries continued to expand well into the 1980s. As the number of active photographers in the region grew, new organizations formed such as the Hamilton Photographs’ Union and the Native Indian/Inuit Photographers’ Association (NIIPA), both in Hamilton. These communities led to a wider array of modes of production through journals, exhibitions, conferences, and community exchanges. Records of these vital interactions shed light on the budding Canadian creative photography field.

The ROM Exhibition

In 1973, students John Bloom, Bill Grigsby, John Luna, Roger Schip, and Clare Schreiber decided they would organise an exhibition and accompanying catalogue of photography and mixed-media work by Ryerson students. They aptly named the venture Ryerson: A Community of Photographers. Faculty and students were encouraged to submit three pieces each for review and selection. Bill Grigsby later explained the motivation for the exhibition as being highly influenced by the students’ exposure to American exhibition catalogues. The Ryerson: A Community of Photographers publication was key to the exhibition organisers as a means of publishing their work and historizing the project. They understood that the catalogue could more easily be distributed and was not restricted to gallery visitors. Exhibitions by their nature are temporal and locally specific. They play a key role in facilitating an audience for artworks locally and as such support a local artist community by displaying their work. Exhibition catalogues help cement these temporal events, allowing the exhibited artists to share their work across vast distances by sending the catalogue to peers in other cities. Moreover, catalogues as books, negate the fleeting nature of the exhibition producing a record of the curatorial thought and production. In cases such as Ryerson: A Community of Photographers such catalogues provide historical insight into the creative output of the student community that would otherwise be difficult to trace.

The exhibition, Ryerson: A Community of Photographers was held in the lower rotunda of the Royal Ontario Museum between March 26 and April 21, 1974. Student organizers made postcard invitations and sent them out to individuals and journals – including Afterimage – announcing the upcoming show. In 1972, Afterimage began publication. The journal was published by Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester under the leadership of Nathan Lyons. It quickly emerged as a vital source for cultural criticism. Like Ryerson: A Community of Photographers, students of the Visual Studies Workshop played a central role in the journal’s production acting as editors and contributing articles, as well as working on all other aspects of the journal.

The faculty members’ work included in the exhibition and corresponding catalogue was not singled out; rather, it was integrated into the students’ work. Further, while they were supported by the faculty, the exhibition’s conceptualisation and realisation was entirely carried out by the students. The exhibition and catalogue demonstrated the blurring of lines between faculty and students. As the medium was developing as a creative discipline, faculty members relied on their students to help form, shape, and nurture their local artistic networks. The lack of institutional support for photography as a creative medium meant that those who understood photography as such relied on one another for support. Moreover, the rapid expansion of photography education meant that many of the faculty members were close in age to their students. This obscuring of hierarchy was welcomed by some of the faculty members. Phil Bergerson described the exhibition in terms of a whirlwind, one in which he saw little distinction between himself and the student organisers. Part of this association was due to Bergerson’s proximity to student life, as he had been a student himself in the department only a few years prior. He later stated that he was taken aback by the students’ ability to organise the exhibition and was impressed that they had succeeded. The experimentation present in the exhibited work Bergerson credited to the students’ involvement in the photography community at large.

Extensions Department at the Art Gallery of Ontario

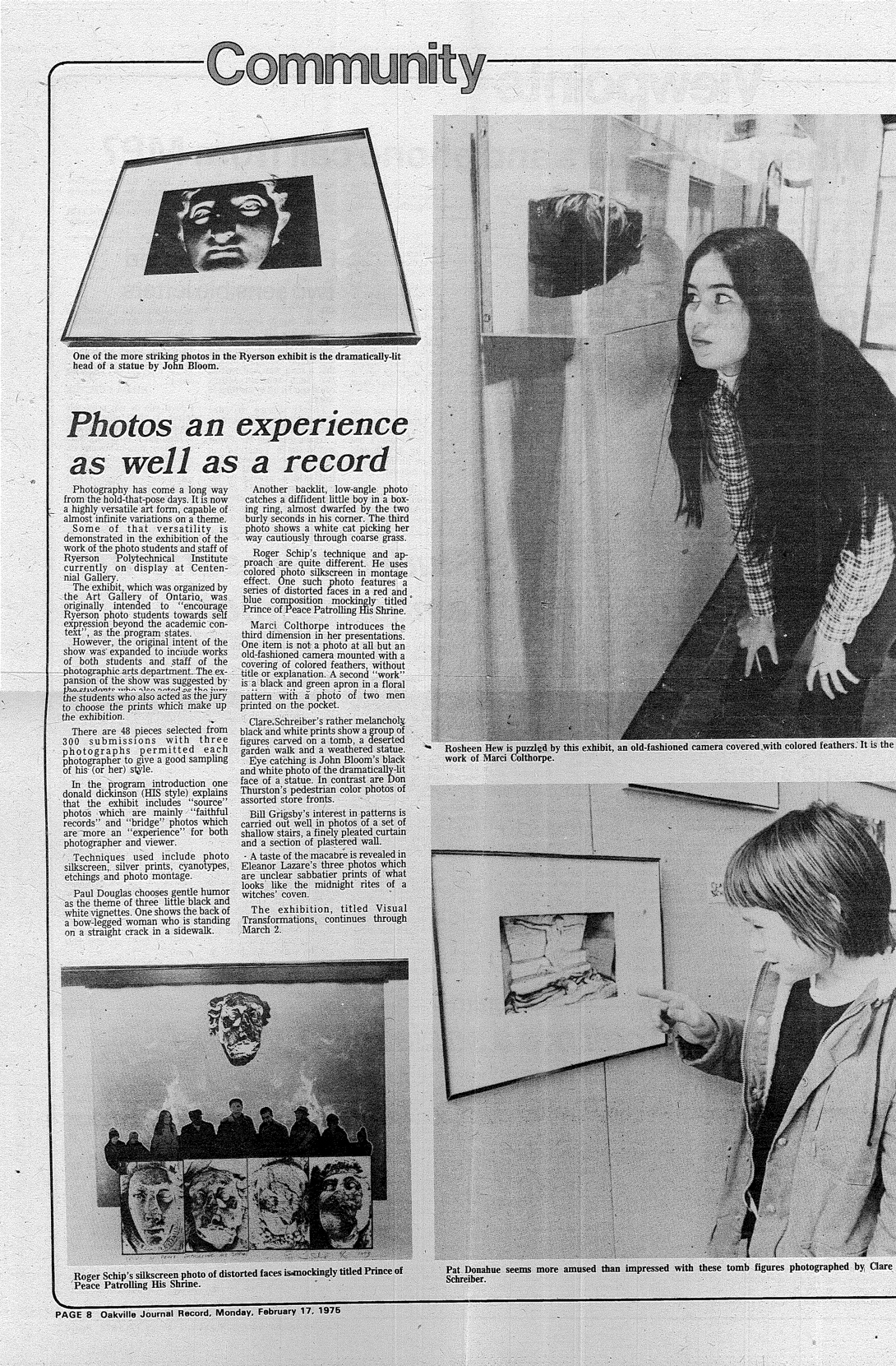

After the exhibition concluded at the ROM, the student organisers were able to secure the travel of their exhibition through the Art Gallery of Ontario’s (AGO) Extension Program under a new title Visual Transformations. Such partnerships were not facilitated through official channels, such as an institutional partnership, but rather through the connections made with individuals within the local photography community. This relationship illustrates the students drive in promoting their work. Over the course of three years, the exhibition was presented in twelve locations: Elmira District Secondary School; Sir Sandford Fleming College; Brampton Public Library; Toronto New College; Oakville Centennial Library; Elliot Lake Centre; T. D. Centre; Trinity College School; Kenner Collegiate; Parry Sound [location not specified]; Atikokan Centennial Museum and Public Library; Orillia Public Library.

At the time, the AGO did not have a formal department charged with curating and collecting photography. This was tied to the biases of the established art world towards the medium, which viewed it as having less artistic merit than painting or sculpture. As such, photography exhibitions held at the AGO were frequently organised by the Extension Services Department. Extension Services was tasked with coordinating circulating exhibitions, lectures, and programs throughout Ontario. These exhibitions, displayed through the 1970s and 1980s, can be seen as both establishing Canadian photography practices and enforcing the developing canon. In 1975 for example, the AGO held Exposure: Canadian Contemporary Photographers an exhibition of over 200 Canadian photographers from across the country. Like Ryerson: A Community of Photographers the catalogue from Exposure remains a key record of the exhibition as it documents a moment in the emerging Canadian creative photography network.

Today, Ryerson: A Community of Photographers catalogue still acts as a vital record of the students and faculty members creative output in Canada in the 1970s. By probing the conditions under which this object was produced, we can learn more about the realities of the local artistic community. The diversity of work included in the pages of the catalogue demonstrates the fluidity in affixing a stylistic approach to define artistic photography.

About the Author

Tal-Or Ben-Choreen, PhD is Curatorial Coordinator at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Her areas of expertise include American and Canadian photography between 1960 and 1990 which she explores with particular emphasis placed on social networks and institutional contexts. Her curatorial projects include the AGO’s 2023-2024 exhibition Building Icons: Arnold Newman’s Magazine World, 1938 – 2000, co-curated with Sophie Hackett. Ben-Choreen’s research has been published in the History of Photography journal, Contemporary Review of the Middle East, Canadian Jewish Studies, and Afterimage Online.

Further Reading

20005.001.08.05.15, “Community Engagement and Corporate Sponsorship” folder, Kodak Canada Corporate Archives and Heritage Collection fond, Ryerson University, Archives and Special Collections, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Ben-Choreen, Tal-Or. “The Institutionalization of Creative Photography’s Higher Education in the United States and Canada, c. 1960-1989.” PhD thesis, Concordia University, 2021.

Blackflash [Special Education Issue] 2 (Fall 1984).

Bloom, John, Bill Grigsby, John Luna, Roger Schip, and Clare Schreiber, Ryerson: A Community of Photographers. Toronto: The Ryerson Community, 1974.

Chartrand, Rhéanne. #nofilterneeded Shining Light on the Native Indian / Inuit Photographers’ Association, 1985-1992. Hamilton: McMaster Museum of Art, 2018.

Doucet, Claude W. “A Brief History of Ryerson University,” Ryerson Archives and Special Collections, accessed January 28, 2020, https://library.ryerson.ca/asc/archives/ryerson-history/brief-history/.

Exposure: Canadian Contemporary Photographers. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1975.

Falkr, Lorne. “The Dilemma of Photography in Canada,” Photo Communiqué 1. 2 (May/June 1979): 15-17.

Kavanagh, Anne. “Private Collections & Public Exhibitions: the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Respond to Photography.” MA thesis, Ryerson University, 2014.

“Kodak in Toronto, 1899-2005: A Century of Traces,” January 5, 2015, Ryerson Archives and Special Collections, accessed July 8, 2020, https://library.ryerson.ca/asc/2015/01/kodak-in-toronto-1899-2005-a-century-of-traces/.

Langford, Martha. “Hitching a Ride: American Know-How in the Engineering of Canadian Photographic Institutions,” in Narratives Unfolding: National Art Histories in an Unfinished World. Ed. Martha Langford. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017: 209-230.

McManus, Karla. “Producing and Publishing The Banff Purchase: Nationalism, Pedagogy, and Professionalism in Contemporary Canadian Art Photography, 1979.” Journal of Canadian Art History 36.1 (2015): 76-101.

Payne, Carol and Andrea Kunard. “Writing Photography in Canada: A Historiography,” The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada, eds. Carol Payne and Andrea Kunard. Montreal and Kingston: McGill- Queen’s University Press, 2011: 232-240.

Ryerson Polytechnical Institute. Canadian Perspectives: Conference Transcript. Toronto: Ryerson Institute, Photographic Arts Department, 1979.

Szikora, Erin. Visual Sovereignty and the Making of NIIPA: Tracing an Archival History of the Native Indian/Inuit Photographers’ Association (1985-2005/2006), MA thesis, OCAD University, 2020.

“Visual Transformations” file, Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.