Pas de deux, (1968)

by Marcus Jack

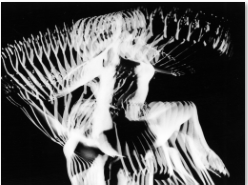

A couple of flecks of light emerge from the centre of a vast black field. Ambiguous and fluid, they soon consolidate into something legible; an arched back pulls the forms into figuration. The silhouette of dancer Margaret Mercier stretches, rising to a standing position. She is backlit from two off-screen light sources on either side, rendering only the edges of her body visible. The image is pushed to extreme contrast. Mercier steps forward to occupy more of the film frame, before withdrawing, spirit-like, and leaving a static double suspended in space. A dance of multiples and mirrors, Scottish-Canadian filmmaker and artist Norman McLaren’s Pas de deux (1968) unfolds as a study of motion, sparing in its technique and beguiling in effect. The ballerina’s solo is soon intruded upon by danseur Vincent Warren and the two begin a courtship, structured around key poses and resolving in the union of their forms. Any expectations of a conventional narrative arc, however, are fast dispelled by the 13-minute film’s intensive experiment with form.

Shadowplay

Shot at half-speed on black and white 35mm Kodak stock, Pas de deux explores the palimpsestic possibility of multiple exposure, manipulating the capacities of photochemical film to capture layers of light. McLaren explains, “the same shot was exposed on itself, but each time delayed or staggered by a few frames. […] When the dancers started to move, each exposure would start moving a little later than the preceding one, thus creating the effect of multiplicity.”[1] In effect, this process—which doubles, then triples, rising exponentially to six, nine, and eleven overlays—creates a metamorphic geometry, finding coherence in stillness before exploding in movement. In this visualisation, McLaren’s images invoke the proto-cinema of early photographer Eadweard Muybridge who sought to capture human and animal movement through sequential still photographs, or the ambition of subsequent avant-garde artistic movements which variously attempted to collapse viewpoints (as in Cubism) and motion (as in Futurism) into a static whole.

With the added dimension of time, however, McLaren leverages film media’s experiential quality to heighten dramatic impact. Nowhere is this manipulation clearer than in the work’s audio. Reworked from a panpipe rendition of “Song of the River Olt” by Constantin Dobre and the United Folk Orchestra of Romania, music editor Maurice Blackburn’s sound design of twinkling percussion and long-held, reverberating strings complement the film’s stark visuals, further lending the dance an almost spiritual sensibility. Despite its remarkable economy of form, Pas de deux is decidedly theatrical. The fantastical images which result from the overlays, solicit an awe that serves a central, romantic vision. While contemporary avant-gardes in Europe and North America had been increasingly concerned with interrogating photographic representation, forming structural critiques of the truth of film, McLaren’s tendency towards spectacle and illusion renders him something of an outsider to the modernist movement.

Rethinking contingency

Norman McLaren’s films are not easily categorized. They draw from the disciplines of drawing, dance, photography, and classical and popular music with little discrimination. Unlike the postwar avant-garde of the artists’ film co-ops in London and New York, McLaren’s work was largely produced under conditions of employment: at the General Post Office Film Unit in London (1936–1939), then the National Film Board of Canada, Ottawa/Montréal (1941–1983).[2] Serving the interests of these patrons, his artistic practice reflects an immutable sense of contingency. Included amongst McLaren’s works are several public information films that make their state-sponsored origins very clear. Less obviously, however, his most abstract works were also commissioned under the pretence of advancing broader national interests—requests for funds at the National Film Board of Canada consistently stress the novelty of processes and techniques, deprioritizing claims upon artistry and subject.

The commercial influence upon McLaren’s work accounts for his exclusion from discourses and histories of avant-garde filmmaking for some of its key promoters.[3] McLaren, meanwhile, voiced a disinterest in the strictures of conceptualism above values like craft, beauty, storytelling, and entertainment—later confessing “I always try to make my films as short as possible. I have a horror of boring people.”[4] In making these concessions, McLaren achieved significant recognition within the realm of mainstream cinema. Pas de deux won a BAFTA (Best Animated Film, 1969) and was nominated for an Academy Award (Live Action Short, 1969). It was also amongst his most expensive projects.

Filmmaking has been recognised as both an art and an industry since the earliest avant-garde cinema of the Surrealists. Unlike the traditional media of painting and sculpture, the production of moving images has always necessitated specific resources including but not limited to: equipment, display apparatus, lab services, consumables and technical support. Artists’ film, as such, has been uniquely compelled to negotiate this tension. McLaren’s unapologetic participation in the cinematic mainstream afforded him a degree of economic security which was rarely available to artists. The choice to make a living at the expense of total creative freedom, however, has led to his omission from histories of artists’ cinema. Knowing the cost of film production, this exclusion could be reinterpreted as a failure of an avant-garde logic to recognise the degrees of contingency inherent to all forms of film. In this way, McLaren’s work raises the question of what really distinguishes avant-garde and commercial in this period?

Into the light

Described as “the most protected artist in the history of the cinema” by his long-term mentor John Grierson, the storied documentarian and first Commissioner of the National Film Board of Canada, the primacy of McLaren’s institutional affiliation might suggest another reading. As a student in Scotland, McLaren had been a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and in 1935 visited Moscow gaining a deeper appreciation for Soviet theatre, film, and culture. He was also a prominent gay man whose fifty-year partnership with NFB producer Guy Glover was an open secret. Working amidst a renewed Red Scare which followed the Gouzenko Affair and before homosexuality was partially decriminalised in Canada in 1969, we might recast McLaren as a more vulnerable figure whose relationship to state protection was complex. Though offering an attractive prospect for gay makers, the National Film Board benefitted from the ready exploitation of unequal loyalties, allegedly keeping McLaren and Glover’s salaries at a bare minimum into the 1960s.

Emerging from this context of social and political repression, Pas de deux is layered with a more confessional expression. The first in a loose trilogy of live-action movement studies, followed by Ballet Adagio (1972) and his final work Narcissus (1983)—in which queerness is staged explicitly in the romantic dance of two men—Pas de deux marks a pivot in McLaren’s oeuvre towards a more personal conviction, evacuated of the whimsy which had arrested his earlier hand-drawn animation. In working with dancer Vincent Warren, as one of many queer collaborators, for instance, an off-screen network can be imagined. Warren was the storied lover of New York writer Frank O’Hara and the addressee of his significant poem “Having A Coke With You” (1960)—which incidentally likens the dancer’s movements to Marcel Duchamp’s multi-perspectival cubo-futurist painting Nude Descending A Staircase (1912), itself inspired by Muybridge’s chronophotography. Whether or not these connections were conscious, they offer new layers to the film’s assemblage of art historical references. Whilst the carefully choreographed movement of Pas de deux on-screen might uphold normative social values, behind-the-scenes McLaren’s productions established a temporary space and community for similarly marginalized artists.

Beyond its mesmerising affect and technical accomplishment, Pas de deux offers something of a cipher for major crosscurrents in mid-twentieth century art and society. It interfaces with and is a challenge to a shifting paradigm in avant-garde filmmaking whilst serving as a subliminal record of invisible networks on the precipice of gay liberation. For McLaren alone, this film marks the beginning of a long personal journey towards closure and disclosure.

About the author

Marcus Jack is a Lecturer in Contemporary Art and Curation at the University of Exeter. He was a SGSAH Postdoctoral Research Fellow at The Glasgow School of Art in 2023 and a visiting researcher with the Archive/Counter-Archive project at York University, Toronto, in 2022. Marcus develops screening events and publications through Transit Arts (2015–) and is the founding editor of DOWSER (2020–), an open-access serial concerning artists’ moving image in Scotland. He is a Trustee of Glasgow Artists’ Moving Image Studios SCIO (2020–) and has advised on the Steering Group of the British Art Network (Tate and Paul Mellon Centre, 2019–2022) and submissions panels of Glasgow Short Film Festival (2016–2020; 2021–) and Open City Documentary Festival, London (2019–2021).

Further reading

Broomer, Stephen, and Michael Zryd. Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada. Edited by Jim Sheddon and Barbara Sternberg. Fredericton: Goose Lane, 2021.

Curtis, David. ‘Where Does One Put Norman McLaren?’ In Norman McLaren, 47–55. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, 1977.

Dobson, Nichola. Norman McLaren: Between the Frames. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Dobson, Terence. The Film-Work of Norman McLaren. Herts: John Libbey, 2006.

Druick, Zoë. Projecting Canada: Government Policy and Documentary Film at the National Film Board. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007.

Dulac, Germaine. “The Avant-Garde Cinema.” In The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, edited by P. Adams Sitney, 43–48. New York: New York University Press, 1978.

Glover, Guy. McLaren. Montréal: National Film Board of Canada, 1980.

Leighton, Tanya, ed. Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader. London: Tate, 2008.

McWilliams, Donald. Creative Process: Norman McLaren. Canada: National Film Board of Canada, 1990.

O’Hara, Frank. The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara. Oakland: University of California Press, 1995.

Waugh, Thomas. “Two Great Gay Filmmakers: Hello and Good-Bye (1988).” In The Fruit Machine: Twenty Years of Writings of Queer Cinema, 195–207. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Norman McLaren, “Note on the Multiple Image Technique of ‘Pas de deux,’” c.1967. National Film Board of Canada Archive, Production Files, T.17.66. Pas de deux. ↵

- For a comprehensive timeline of his career, see Guy Glover, McLaren (Montréal: National Film Board of Canada, 1980). ↵

- See David Curtis, ‘Where Does One Put Norman McLaren?,’ in Norman McLaren (Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, 1977), 47–55. ↵

- Norman McLaren, letter to Jean-Paul Vanasse, 11 April 1969, P01.B.19, 12598: Correspondance de Norman McLaren (1951–1970), National Film Board of Canada Archives, Montréal. ↵

A pas de deux, or step of two in English, is a common dance duet in ballet, generally performed by a man and woman. In classical form, this follows a strict structure beginning with an adagio, solo variations for the man, then woman, and ending in a coda in which they reunite.

In photography, multiple exposures involve a technique that layers more than two different exposures on a single image, combining multiple photographs into one. This technique or exposure creates a surreal feeling in photographs.

In the 1960s and 1970s, artist communities began to assemble around the Film-Makers' Cooperative, New York (1962–) and the London Film-Makers’ Co-op (1966–1999). The dominant output of these transatlantic co-ops was called structural film and was a movement characterised by intense formalist experimentation with the materiality of film.

The Gouzenko Affair (1945–1946) was amongst the earliest spy scandals in the Cold War. Defecting from the Soviet Union, cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko leaked materials that revealed the existence of a Communist ring operating within universities and government agencies across Canada. The incident prefigured the Red Scare of the 1950s.