In the Conservatory (1883)

by Samantha Burton

In Frances Jones’s Impressionist painting In the Conservatory, a young woman reads in a glass windowed interior full of tropical plants.[1] The setting is the conservatory in the Jones family’s home in Halifax. This might be a familiar, even mundane scene to a twenty-first-century viewer, but it was very unusual for nineteenth-century Nova Scotia. A large collection of exotic indoor plants was a luxury few could afford before the widespread availability of plate glass and the invention of modern heating and ventilation systems. As such, while this painting seems at first glance to be an intimate representation of modern domesticity, it in fact reflects Halifax’s—and Jones’s—place in political, economic, and cultural networks that stretched across the globe.

Modern domestic life

In the Conservatory shows the artist’s cousin Nelly sitting on a wicker chair surrounded by a lush collection of colorful plants and flowers. Wearing a modern dress and casual hairstyle, Nelly reads a book by herself. We see her from behind, her figure framed by the curving leaves of a large green plant in the background. This warmly lit composition emphasizes her quiet solitude. This cozy scene contrasts with the damp grey exterior outside the big plates of glass. Here, the trees have been stripped of most of their leaves and the blurry brushwork gives the impression of condensation on the windows. Comfortably indoors, Nelly seems the very picture of domestic leisure, untouched by the outside world. Absorbed in a book, she turns her back to the viewer. She, like the plants that surround her, might be seen as a delicate object sequestered away in a space dedicated to her care.

Women artists like Jones often painted domestic subjects similar to that depicted in In the Conservatory. Jones’s Impressionist peers Helen McNicoll, Mary Cassatt, and Berthe Morisot all painted women in domestic interiors and gardens reading, sewing, and doing other activities associated with white, bourgeois femininity. Women painted these subjects not because they were naturally inclined to them, but because of their limited access to the modern public spaces—bars, cafés, city streets—painted by their male colleagues.

Although often not recognized as such, the everyday lives of women like Nelly were equally modern subjects, and a new and exciting theme for art. Plant conservatories were popular subjects for artists in the later nineteenth century. Versions of the theme by Morisot, J. J. J. Tissot, and Édouard Manet would have been familiar to contemporary exhibition audiences.

Jones’s painting was exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon, the first painting of an identifiable Canadian location to be given such an honor.[2] Viewers in Paris must have been surprised by the modern luxury of this Canadian domestic interior and the cultured refinement of Nelly herself.

Transplants

But In the Conservatory is not a straightforward representation of a domestic space separate from the outside world. The painting, in fact, suggests political, economic, and cultural networks that stretch across the globe in both its subject matter and style. In particular, the plants and flowers are tropical varieties non-native to Nova Scotia. The plants on display were part of Jones’s father’s extensive horticultural collection, which also included an arboretum on the family’s Halifax estate. The vivid colors of the plants present a striking contrast to the gloomy grays and browns beyond the windows, highlighting their foreignness to nineteenth-century Nova Scotia. The artist includes numerous terracotta pots and a watering can, emphasizing the deliberately cultivated origins of the plants.

Plant collecting has a long history in Western Europe and in settler colonies like Canada and the United States. Beginning in the fifteenth century, this practice was closely linked to European colonization. Plants from across the world came to European attention through colonial exploration and trade. The development of natural history as a field of knowledge was one way Europeans made physical and aesthetic sense of their new worlds. Visual culture played an important role in developing new knowledge about plants and animals, as specimens were chronicled in illustrations that circulated widely. The discipline of natural history also gave colonization a scientific backing and provided a false justification for the exploitation of local labour and natural resources. As part of this process, plants were uprooted from their places of origin and transported to Europe, where they became objects of study, commerce, and display.

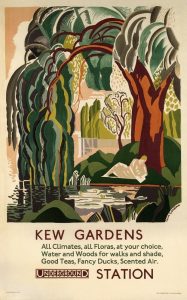

The first modern public Western botanical gardens emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Built for public education and entertainment, botanical gardens promised to make the flora and fauna of the empire visible to the metropole. An advertisement for London’s Kew Gardens, for example, promises “All Climates, all Floras, at your choice.” Kew was home to one of the largest and most extensive plant collections in Europe in the nineteenth century, and its glass conservatory buildings were some of the first and largest of their kind. Jones and her family may have visited Kew on one of their many trips to London—it was a “must see” for Canadians abroad. Another Canadian artist, Emily Carr, wrote about her own experience at Kew, describing it as “a bouquet culled from the entire world.” Smaller-scale private conservatories like the Joneses’ gained popularity in the mid-nineteenth century, inspired by places like Kew. Part of the pleasure these spaces gave to their owners and visitors was pride that they were members of a global community that had the power and wealth to amass such an impressive collection, and the knowledge to transplant, condense, and reorganize the world on their own terms in their own backyards.

The transnational links evident in the painting are based firmly on Canada’s membership in the British Empire. When this painting was made in 1883, Canada was still a fairly new nation. While Confederation in 1867 had united several British colonies as a self-governing country, Canada remained closely tied to Britain politically, economically, and culturally. The Jones family was securely embedded in these networks. Halifax was a key port linking Canada, Britain, the United States, and the Caribbean in the nineteenth century, and the artist’s father was a wealthy merchant and company owner in the thriving West Indies trade market. He was also a politician who was elected to Parliament on an Anti-Confederation platform aimed at preserving Nova Scotia’s colonial trade economy. Photographs, sketches, and written evidence show that the extended Jones family travelled widely throughout the British Empire, trips that made their plant collecting possible.

Although it is difficult to identify and trace the painted plants with any certainty, photographs and another painting of the conservatory show pots of geraniums and clivia, two varieties originating in South Africa. Most prominent in the painting is the large green taro plant at the back of the conservatory. Taro was originally transplanted to the Caribbean alongside breadfruit and plantain to serve as a food source for enslaved people. Here, its broad leaves form an overhanging umbrella that visually shields the reading woman from the rainy outdoors. Hovering over this idyllic scene, the plant’s connection to a history of subsistence and enforced labor is a sobering reminder of the colonial power systems that make this white woman’s leisure possible.

Light and air

In the Conservatory also suggests transnational networks through its style. The painting was one of the first major Canadian experiments with Impressionism, an artistic movement focused on representing modern subjects and experimenting with new compositions, loose, sketchy brushstrokes, and the effects of light and color studied en plein air (in the open air). Impressionists like Jones attempted to represent a more spontaneous view of the world, painting what they saw directly from nature. These qualities are shown in In the Conservatory. While the figure is treated relatively conventionally, the space seems somewhat off-kilter, light glints off each surface, and the brushwork used to represent the flowers and outdoor landscape is loose and sketchy.

Impressionism originated in France but was transported across the globe by artists like Jones, who studied art in Paris. Jones was a member of the first generation of Canadian artists for whom it was common to travel to Europe to attend art school and pursue a professional art career, due to improved transportation and communication infrastructure. Although she would have gone seeking a traditional art education, she also found a more avant-garde approach to art than was available in Canada at the time. Although the painting may not seem especially controversial today, Impressionism was the subject of much debate in the Canadian art world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and unpopular among audiences who found the style too modern.

Although on first glance In the Conservatory appears to be a representation of bourgeois femininity, this is not just a domestic scene shut off from the outside world. Jones’s painting provides evidence of how her family’s household, Halifax, and Canada were connected to global artistic, trade, and colonial networks. By looking closely at the work’s subject and style we can begin to expand the boundaries of Canadian art history beyond the nation’s geographical borders.

About the author

Samantha Burton is a lecturer in the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California, where she teaches undergraduate classes on visual culture, modern and contemporary art, the history of photography, and more. Her research focuses on transnational mobility and cultural exchange in the nineteenth-century British World. Sam is currently completing a book manuscript that examines the ways in which white settler Canadian women artists who lived and worked in Britain managed multiple and often competing ideas about empire, race, and national identity in the decades prior to World War I. Her research has been published in venues that include Victorian Studies, Journal of Canadian Art History, and Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. Her biography of the artist Helen McNicoll, published by the Art Canada Institute, was released in 2017.

Further reading

Atanassova, Katerina, ed. Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880–1930. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2019.

Burton, Samantha. “Transplanting Impressionism to Canada.” In Mapping Impressionist Painting in Transnational Contexts, edited by Emily C. Burns and Alice Price, 65-76. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Davies, Gwendolyn. “Art, Fiction and Adventure: The Jones Sisters of Halifax” Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 5 (2002): 1–22.

Lowrey, Carol, ed. Visions of Light and Air: Canadian Impressionism, 1885–1920. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1995.

Prakash, A.K. Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2015.

O’Neill, Mora Dianne. Two Artists Time Forgot / Deux artistes oubliées par l’histoire: Frances Jones (Bannerman) and Margaret Campbell MacPherson. Halifax: Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2006.

- Although the artist is now often known by the name Frances Jones Bannerman, I use Frances Jones throughout because the work under discussion was painted and exhibited before her marriage to the English artist Hamlet Bannerman. ↵

- Mora Dianne O’Neill, Two Artists Time Forgot / Deux artistes oubliées par l’histoire: Frances Jones (Bannerman) and Margaret Campbell MacPherson (Halifax: AGNS, 2006), 78. ↵

In Paris at this time, there was one official, state-sponsored exhibition—called the Salon. For most of the nineteenth century, the Salon was the only venue for exhibition (and therefore the only way to establish your reputation and make a living as an artist).

A form of colonization that seeks to remove Indigenous populations from their traditional lands and replace them with a new society of settlers.

The Anti-Confederation Party was a short-lived Canadian political party that opposed Canadian Confederation in 1867. The movement was centered in the Canadian Maritime provinces.