Whatever Happened to the Prisoners?

Trust is something that you give. It is a gift.

Nobody can make you trust them.

If anyone demands that you trust them, it’s probably a good clue that you shouldn’t trust them at all.

Introduction

Pay attention[1]. You may need this later.

It’s sort of about games. It’s also sort of about how people make decisions and how, regardless of what scientists, economists, game theorists (or just plain anything-ists) might like, we’re an irrational sort. Actually, that’s kind of important because trust, you see, is not always a rational thing. Let’s see now, it all started with Chuck (Chuck is the one with the mask!) and his co-conspirator Eve getting caught.

Read on…

‘Allo ‘Allo

(Not the TV show, which was good, but what the police officer says…) Chuck and Eve were out on their usual nefarious business being less than good. It so happened that Officer Crabtree, our police officer, was following them. Naturally they got caught. That’s how it works.

Now Officer Crabtree chats with his captain, who says, “This pair have done a few heists. Make ‘em squeal” (that’s how police captains speak). They’ve got our pair of criminals bang to rights on this heist so they use it as leverage. Let’s see how that works.

Chuck is told, “We know you did other things, tell us what you know about Eve’s involvement and you can go free!” (A plea bargain no less.) Naturally there’s an ‘or else’ which goes like this: “If you stay quiet, Eve will rat on you and you go down for the lot whilst Eve goes free.”

Eve gets the same ultimatums.

To translate a bit: Both get told they can rat or stay quiet and the results will depend on what the other said. Trouble is, they can’t talk to each other and make a pact.

It’s a dilemma.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

[2].

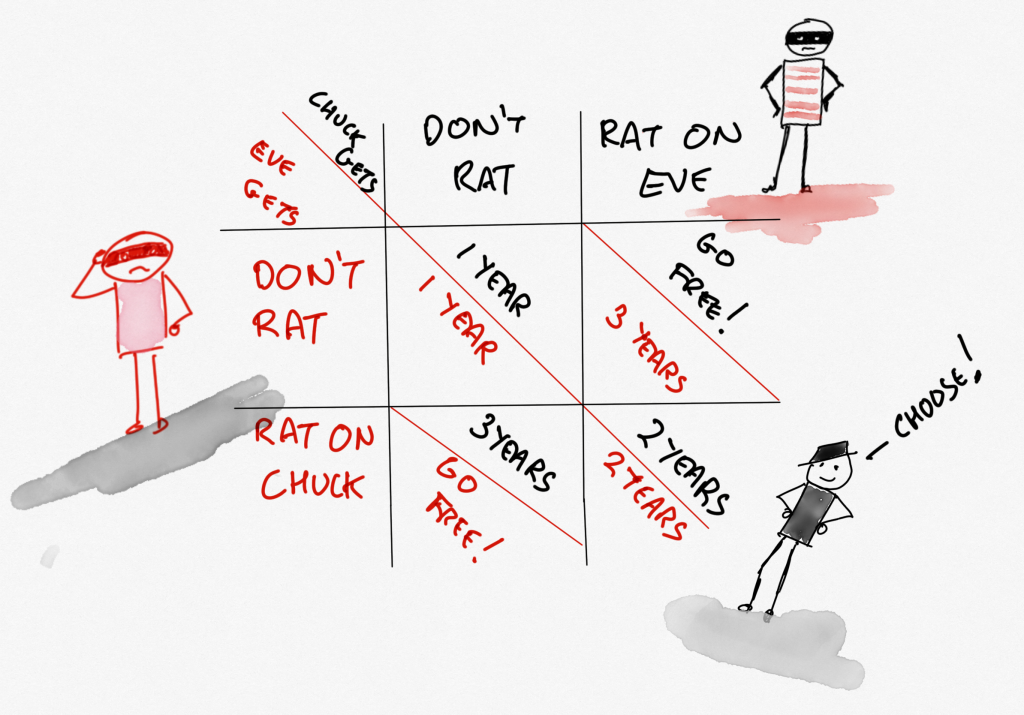

To recap, Chuck and Eve can’t talk to each other and they’re faced with a choice – rat or stay quiet. Each can’t tell what the other will do until it’s done.

Well, what would you do? Be honest, there’s no-one here but us. To make it more interesting, let’s add a little more nuance.

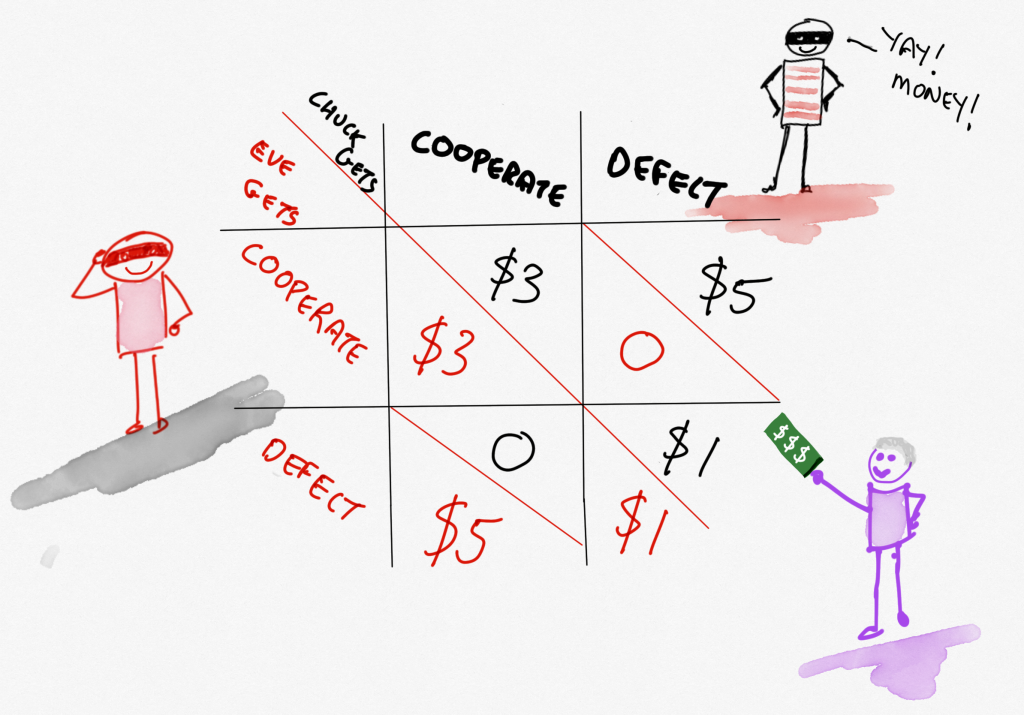

If Chuck rats on Eve and Eve stays quiet, Chuck goes free; but Eve, who has now had a bunch more bad stuff pinned on them, has to serve three years. The same would happen to Chuck if Chuck stayed quiet and Eve ratted. There’s more. If Chuck and Eve both stay quiet, they’ll serve the one year that they would get anyway for the heist they got caught in. And if they both rat on each other, they get to spend two years in jail for admitting to more than the heist they got caught in. I hope that makes sense.

This is a pretty pickle, and can be represented by a ‘matrix’ of sorts. There it is look![3]

A little thought will suggest to you that the best both could do was to stay quiet and hope the other does too. If they get ratted on, though, they will get three years! So that’s not a good thing, right? So maybe they should just spill the beans! (But then they’d get two years instead of the one they would’ve got if they’d stayed quiet! Free is good. Jail is not.

Let’s Make It a Game!

The thing is, Eve and Chuck just have to make this choice once. What happens if the choice happens again? And again? And again?

It’s kind of like this: if they both know how many times they’ll have to make the choice, they’ll both just rat on each other every time because, well, they’re going to rat in the last stage and so they will have to rat on the previous one, and so on. See how that works?

Men are not prisoners of fate, but only prisoners of their own minds.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

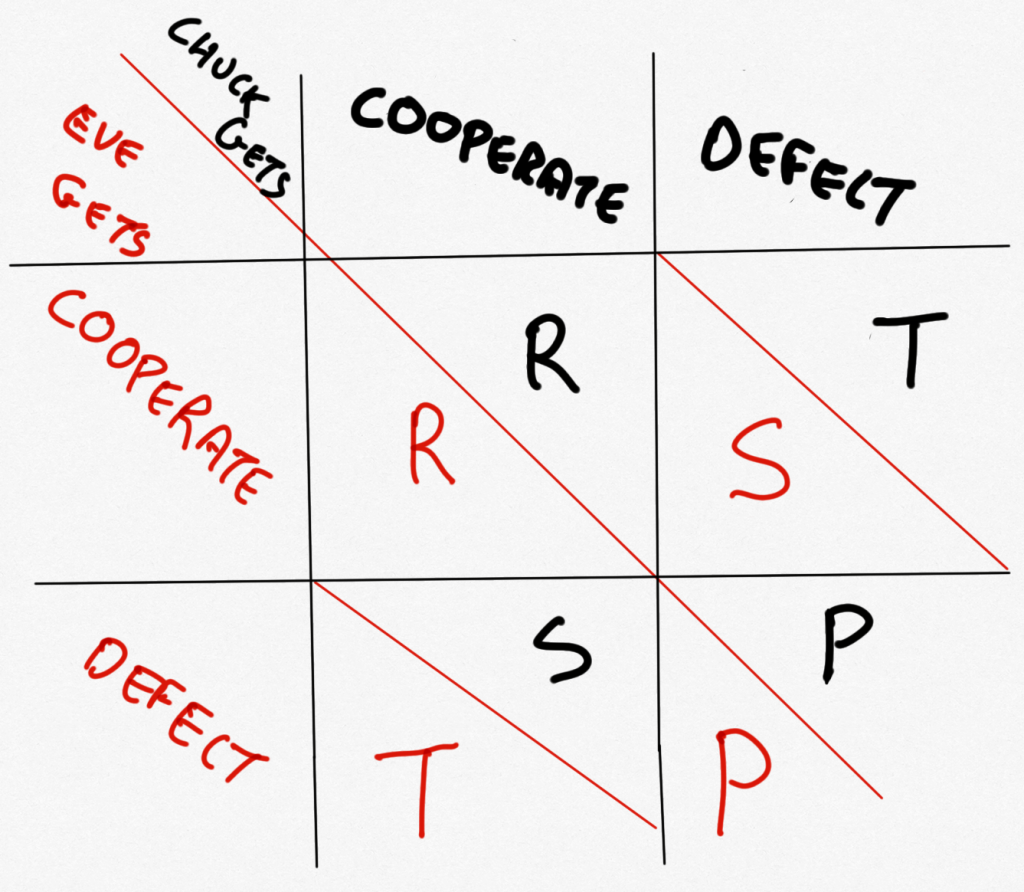

It becomes much more interesting if they don’t know how many ‘rounds’ they will have to ‘play’. At that point they can’t be sure what’s going to happen and so perhaps the best strategy is to stay quiet? Imagine if the choices were for money instead of jail time. For this, let me introduce Alex[4], our game show host. Hello, Alex. Now in our game the competitors get a similar choice to the crooks: cooperate (stay quiet) or defect (squeal). If they both cooperate they get a Reward for cooperation, which is, say $3. If they both defect they get a Punishment, still a bit of money but just $1. If one cooperates whilst the other defects then the one who cooperated gets a Suckers payoff. Basically nothing. And the other? They get the biggest money – a $5 Temptation to defect. See those bold letters? Good.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll have noticed that those red, underlined letters are worth something. For this thing to be a Prisoner’s Dilemma, they need to be arranged in a particular way: T>R>P>S. You can see that in the picture (I hope!) You can make all kinds of games around this and the dilemma remains. It’s pretty neat (and simple)

The Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) has been the source of many different studies since its inception in the 1950s by two RAND researchers: Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher, and its subsequent codification and description (using the prisoners we know today) by Canadian mathematician, Albert Tucker. To bring it to our more recent past, let’s talk about a couple of tournaments run by Robert Axelrod in the 1980s (Axelrod, 1984). Axelrod is a political scientist and was examining the dilemma as a kind of lens for looking at how decisions can get made in the context of international relations (it’s a long story and has roots in the Cuban Missile Crisis — if you’re interested, here is a very nice telling of the story). It’s worth noting that Flood and Dresher didn’t ‘invent’ the Dilemma – it’s always been there, but they identified how it kind of works (and that T>R>P>S relationship. Actually, it happened to be a really good explanation for mutually assured destruction (MAD) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (CES, 2019).

Before we go too much further and people get all excited about games and Game Theory–yes, it is neat and yes, we can explain or even possibly try to predict behaviours (or maybe shape them the way we want). But people aren’t rational and people don’t behave according to simple assumptions. Sure, you can definitely use it to generalize and even study over vast quantities of people and economic behaviour, and it has been done. I have always thought of it a little like Asimov’s (Seldon’s) psychohistory – it works, but there are some assumptions and restrictions. To put it another way, “Applied in the right way— by understanding the motivations of those who participate and the social norms that guide them — game theory can successfully predict how people will behave and, similarly, its techniques can help in economic system design.” (Wooldridge, 2012). The trick? understanding[5]

Anyway, back to Axelrod. He built a computer program that ran a tournament for the PD which would face off different strategies against each other for a number of rounds (the number being unknown to the strategies). He asked several notable social scientists to submit code for the strategy they would like to run and pit them all against each other in a kind of round robin tournament.

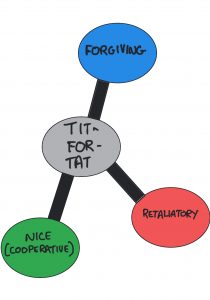

The results were surprising: the strategy that did the best, submitted by a social scientist and peace studies researcher, Anatol Rapoport[6]. It goes like this: cooperate first round, then do whatever your opponent does on the previous round for your next decision. So, it was nice: it cooperated first, but if you ever defected against it, it would assuredly defect back (which made it provokable). It was also forgiving because, well, if you subsequently cooperated, it would too. Tit for tat. Nice, provokable and forgiving.

Axelrod, being on to something, then put ads in various journals for people to submit their own strategies, telling them which one had won the previous tournament. Lots of very complex and sneaky algorithms were submitted, the tournament went again and… tit for tat won again. Pretty neat eh? What is the take-away from all this? Well, being nice, provokable and forgiving is pretty good.

Finally, it became very clear to other strategies exactly what tit for tat would do next: it was predictable and clear in its intentions.

What does this mean for cooperation? What, in fact, does it mean for trust, since this is a book about trust?

It’s like this: tit for tat never actually won any of its games, if winning means ‘got the most points,’ it just pushed every other strategy to do better. Why? Because it basically encouraged cooperation. You can never do better than cooperating against tit for tat (unless of course you came across a complete sucker who always cooperated no matter what you did!) But more to the point, strategies playing against it began to cooperate because it was the sensible thing to do. It’s a pretty neat thing and Axelrod went on to do a whole bunch of research into tit for tat in many different fields, from political science to molecular biology.

If Tit for Tat encourages cooperation, what does that tell us about trust? On a simple level, it tells us that if you are clear in your intentions and you always do what you say you will, it becomes pretty easy to trust you in that particular context. If I know you’ll poke my eye out if I poke yours, I probably won’t try to poke yours out… And so, it’s not necessarily trust in the other (it probably goes without saying that the USSR and the US didn’t trust each other) but trust that you will do as you say (“Bomb us, and we will bomb you back to the Stone Age”).

I mentioned earlier in the book that trust is contextual. It is. It’s also very sensitive to the what for question. What is one agent trusting another for? What is it they are trusted to actually do? Here, Tit for tat shows us that we can trust it to do exactly what it says it will. That’s an important thing. We can take this into a different direction and think about why cooperation happens. Why do, for example, some animals help each other out? Are they just being kind? Let’s dive into evolution and stuff for a little bit.

Hamilton’s thought (Hamilton, 1963; 1964) was that natural selection favours genetic survival, not, as you may have thought, a particular species’ reproductive success (it’s called Hamilton’s Rule). So, because the genes ‘want’ to survive, animals in the same species who are also kin will help others (like vampire bats sharing blood with those who haven’t fed that day – for an excellent discussion of which, see Harcourt, 1990). Altruism is about helping the genes survive at some cost to the individual, in other words. It becomes a bit mathematical and has to do with the number of shared genes and stuff but it’s interesting explanation for some altruistic behaviour. Richard Dawkins took at look at that in The Selfish Gene (Dawkins, 1976[7]). So, altruism might actually evolve because it is good for the population, to put it (far too) simply.

This brings us to reciprocal altruism – doing something nice because you expect it will come back as something nice for you). It goes along the same kind of lines and is sort of explained by things like kin selection. But how does that all work in humans? After all, we do nice things for other people all the time (and sometimes not expecting anything back – call that ‘real altruism’). One thing we might do is something nice in the expectation someone will do something nice back to us (call it ‘calculated altruism’). In other words, there’s some form of quid pro quo.

What has this got to do with trust? Think about it this way: it’s entirely possible you could do something really nice for someone at some cost to yourself in the expectation you’ll eventually get a reward of some sort from them. There’s a risk, of course, that they won’t do anything for you at all. So in effect you are trusting them to be nice back. Trivers (1971) suggests that trust and trustworthiness (two distinctly different things) as well as distrust are actually ways of regulating what are called subtle cheaters.

It works sort of like this: trustworthiness is something that is exhibited by a trustworthy person, right? So if someone wants to be seen as trustworthy (and thus, get the nice things) they will behave in a trustworthy manner (by repaying the nice things). If they don’t, they will become distrusted (because, well, nobody will do nice things for them if they’re just nasty). And so it goes. Cheaters are encouraged to be trustworthy simply because being trustworthy gets nice things. Nevertheless, cheaters do exist, and there are plenty of strategies to manage this kind of regulation for cheaters, which we’ll get to later in the book. Still, it sometimes does pay to be ‘good.’ It also sometimes pays to be able to look like you’re good (see Bacharach & Gambetta, 2000).

Okay, so the Prisoner’s Dilemma is all nice and everything, and in a while we’ll come back to it, because as I’ve mentioned before Deutsch did a bunch of research with it too, back in the day. But before we go there, let’s visit the Commons.

The Tragedy of the Commons

I’ve already mentioned Hobbes and his famous Leviathan. Well, to be fair I’ve mentioned Hobbes and quoted from Leviathan (Hobbes, 1651) (that bit about nasty, brutish and short) which was really arguing that people need governments to be able to be ‘good’ because governments could punish people who were ‘bad’[8]. Well that’s great, you think, but I want to take you to another kind of argument, and to do that, we need to think about what is called The Tragedy of the Commons. It was brought forward in a seminal paper by Garrett Hardin. Imagine if you will…

Not clear enough? Try this: in a situation where some kind of resource is shared, it just makes sense for individuals to try to use as much of it as possible. That’s a problem because doing that is bad for everyone as a whole. This relates to the Prisoner’s Dilemma right? How? Because once again we are asked to believe that people are rational. Read on.

There may well be a way around this problem, and in Hardin’s paper the suggestions are privatization or government regulation. Both of these can work because all of a sudden the private individuals want the resource to last in the first case, or the government can punish them if they don’t in the second case (remember Leviathan?). To put it another way, humankind is basically screwed because it’s too self-interested and overexploits its resources.

Okay then, this of course means we’re basically not going to survive. At this point, we can either pack up and go home or turn to Elinor Ostrom.

Ostrom was a political economist, and one of only two women ever to win the Nobel Prize for Economics for the work she did on the Commons, which may well save us all, or at the very least provides a path.

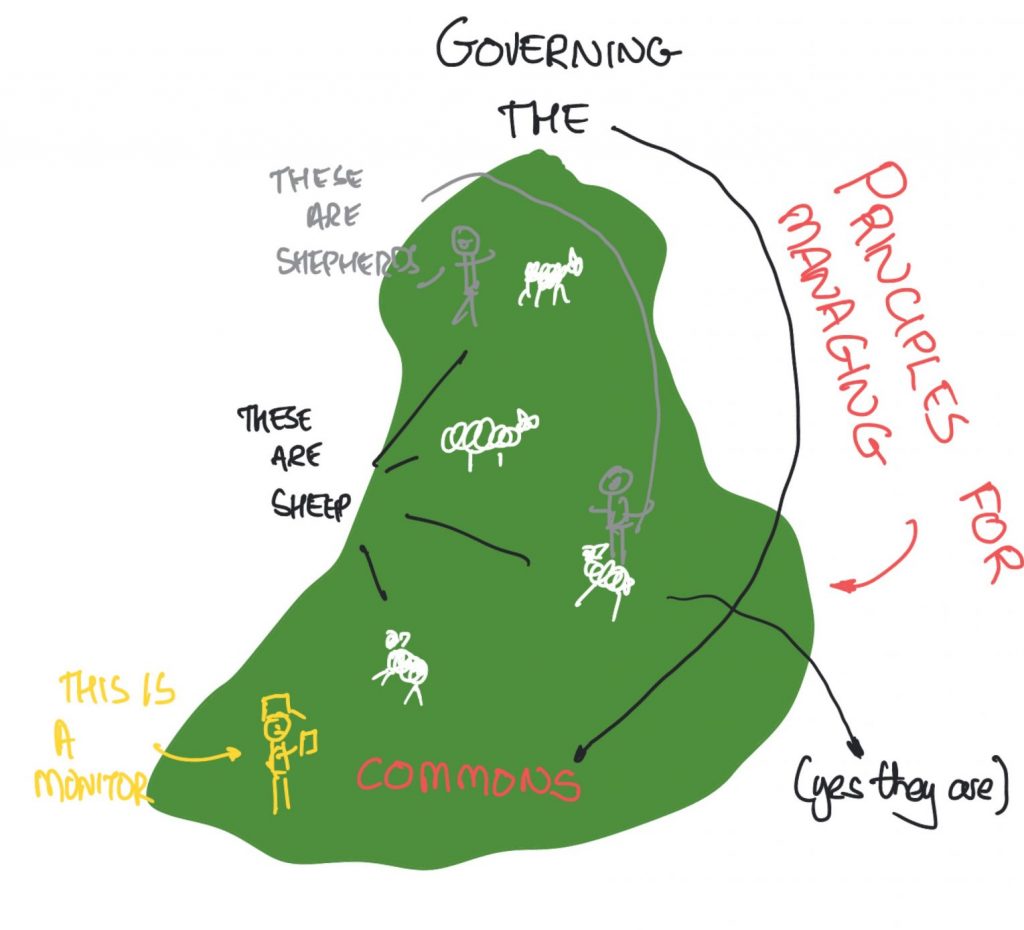

Governing the Commons

It goes like this: understand institutional diversity. “What are you talking about?” I hear you say.

Let me explain. Sure, you can privatize resources, but in the end, there are always people who will try to rob you. You can rely on governments, and sure, that can work if the government itself understands what it is trying to protect. There are examples of where these kinds of solutions just don’t work (fisheries, for example) for various reasons.

But Ostrom in her research found that there are examples of where the ‘Commons’ was a shared (private to the individuals sharing it) resource and was sustainably managed, harvested, or whatever. By the very people who used it. How can this be? Because the people who were using that resource had recognized that the answer to the question of shared resources was not ‘it’s this or that’ but in fact was ‘it’s complex’. That means that they figured out that the resource they were sharing was a complex system within a set of other complex systems and that it needed a really complex set of rules to ‘govern’ (and thus share) it. There are examples of this from lobster fishers off the coast of Maine to Masai tribesmen in the bush grazing cattle.

What have we learned here? That complex problems sometimes involve complex solutions, and, well, simple games aren’t always the answer.

To paraphrase what Ostrom found in two words, in one sense we are talking about sustainable development. Or perhaps we are talking about managed commons. And did you notice something else? It comes down to the trust that the people in the local system have in each other, because they need to trust each other to make this work!

Well, sort of. In fact, Ostrom introduced a set of ‘design principles’ for how to manage a commons (technically a Common Pool Resource (Commons), but you get the idea). The book is a little academic, so I’ll do my best to do the ideas justice here. I’ll also perhaps order them in a way different than you may see them elsewhere. That’s okay – as long as the eight are there, you’ll do fine.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that there is a resource (the Commons) and there is a group of people who want to (or must) share it for their own well-being. Once you realize that, the first of the principles becomes clear: there has to be a clearly defined group and a clearly defined Commons, so that everyone knows within the group that they are in it, that others are not, and what it is they are making rules about for sharing. Because this is all about rules: how to use, who can use when, how much to use, and so on. So the second principle is to match the right rules to match the local conditions that the Commons is found in. It may be, for instance, that even though the Commons is the same between different groups (land, say, or water) the local conditions can be very different. When the rules are matched, things are good.

This brings us to the rules themselves, because the third principle is that the rules are made, and can be changed, by the group of people who are using the Commons.

Why does this matter? Because the people using the Commons are the people who are local enough to be able to understand what works. They’re also the ones ‘on the ground’, as it were, and so the fourth principle comes into play: there needs to be a system for monitoring how the rules are followed – this can be amongst the people using the Commons or some third party – and we’ll talk more about monitoring in a bit. But when you monitor, you may well find that some people are breaking the rules and using just that little bit more than others, for instance. In that case, there needs to be some form of punishment (Ostrom calls them sanctions) for breaking the rules. The people who do the punishing may be the people who use the Commons and set the rules, but they could be some other third party again, which is fine as long as they answer to the people who use the Commons. I’m sure you can understand why – after all, if the punishers are not accountable, they could do whatever they wanted with impunity[9]. For the fifth principle, it is important to note that these sanctions should be gradual in some way. Sometimes a slap on the wrist, or diminished reputation, is enough to bring people back in line, especially if the infraction was small. Bigger, or more prolonged bad behaviours likely need gradually bigger punishments. You get the idea.

Now it gets even more interesting because, well, sometimes people disagree on what is happening and that’s no good! So, there needs to be some form of conflict resolution system that everyone agrees to. When we say everyone we mean both the people using the Commons and, if there are any, the third parties that do the monitoring and sanctioning – that’s because there may well be times when they disagree too. So, the sixth principle talks about how there need to be fair and agreed upon ways of resolving these disagreements. The emphasis is on purpose. If people start thinking that things aren’t fair, they’re going to stop trying to care.

Of course, we’re usually talking about a Commons that exists inside, say, a country, and isn’t the whole country. Clearly, the people who use the Commons are probably not the leaders of the country! The thing is, the leaders of the country (or what Ostrom called ‘external authorities’ – so it may be the local council or the provincial or state government, and so on) need to agree that the people using the Commons know best, ultimately, and are allowed to makes these rules and choose sanctions, and so on. This is the seventh principle, and if they decide that this isn’t allowed, usually things go bad because in general they don’t understand how the Commons itself is used – and so at least principles 2 and 3 are not followed. Usually this results in the Commons being over-exploited and, ultimately, early lost. A whole chapter in Ostrom’s book is devoted to these sadly avoidable instances.

Still, this is important: there are outside authorities, and more often than not, they have their own sets of rules and are themselves part of bigger conglomerates: cities, councils, provinces, countries, and so on. Each of these higher levels may actually use or benefit from things that are associated at least with the Commons in the first level (like streams flow into rivers, or rivers to the sea, and what happens to one can seriously affect the others. And they need their own rules for how these are managed. So the eighth principle is that this is complex and that to be successful you need to have nested levels of complexity from the initial Commons all the way up. Rules that are missing or inappropriate in any level will seriously limit the ability of other levels to be successful.

Well that sounds just fine, and I think we can (mostly) all agree that sustainability is a wonderful thing. But what has this to do with trust?

Okay then, let’s see. First, the people need to trust each other enough to come together and make some rules. Then we get to the monitoring and sanctions bits, and it gets really interesting. If the people utilizing the Commons don’t trust each other, or think there could be infractions, they need to spend a lot of time and effort monitoring to make sure everyone is behaving. Okay then, sometimes this is too much for everyone concerned – they have their own jobs to do, after all! So, as we noted, third parties can be used to monitor and sanction. “Now then,” you may be thinking, “that’s all very well, but you just said monitoring costs something. People won’t do it for nothing.”

This is true. There are usually rewards (prestige, goods, money) for being a monitor. Ostrom notes though that “the appropriators tend to keep monitoring the guards, as well as each other” (Ostrom, 1990, p.96). This is an important point in our own narrative, because it implies that there needs to be some form of trust between people and guards and vice versa. The less the trust, the more the monitoring (which costs you!). You have to trust the system to make sure that it will enforce its rules.

And then, there needs to be trust between the external authorities and the nested systems within, all the way down to our original common resource and back again. Trusting the authorities to do the right thing (even if the authorities are those who sanction in our name) or the system to do the job of trust for you (because it ensures the rules are followed) is what we call system trust, and it’s pretty important notion that we’ll revisit later in the book.

It should be pretty clear by now that trust is a central component of the ways in which these resources are managed. Interestingly enough, trust itself can be seen as a Commons, and exploited in various ways – and people often talk about how trust gets used up or destroyed by things that happen or systems that exploit it. We’ll come back to that too.

Can we do this without trust, though? I’m glad you asked, because in another excellent book, which is part of the Russell Sage Foundation series on trust, the authors argue that we can. The book, Cooperation without Trust? (Cook et al, 1995), argues that there are institutions, practices, norms and so on that we put in place to be able to manage in a society without having to trust those we are dealing with. This may well be so: we have legal eagles looking out for us all the time, and police monitoring us, courts to impose sanctions, and so on. The question is, what happens when you stop trusting them?

I said earlier that trust was important in the systems Ostrom explored, and I hope I’ve made it clear where it can be important, whilst (with the help of Cook et al.) it’s also possible to look at it from the point of view that trust is at least sidelined by the systems that are put in place to enable people to be able to go through their daily lives, commerce, and so on, without thinking about trust all the time. It’s complicated, you see.

What’s really neat about all of this is that it has been taken (the principles) and embedded into computational structures to examine, for example, what rules for monitoring might be decided upon in self-organizing systems, which are usually computational systems which are sort of distributed, and sometimes (often) without some form of central control. Sometimes we might have ad hoc networks, for example, or a multi-agent system (MAS). An important body of work leverages Ostrom’s principles into these systems.

And that brings us all the way back to Jeremy Pitt. For whom, see here!

But it doesn’t stop there. Up to here I’ve brought you through some of the thoughts of people who have been thinking about this for a long time. However, I did say at the start of the book that it is about computational trust. And so it is, which is why we didn’t dive too deep into the mists of trusty time – don’t worry, there’s plenty of space left for the second edition! The thing is, as with ice-nine, the things I’ve talked about so far are the seed of the computational side of things: look at different pioneers and you’ll likely get a far different form of computational trust.

Because there are far different forms from the computational trust that this book focuses on.

Without further ado then, let’s consider: for something to be computational possible, it must be ‘reduced’[10] to a state that makes sense to computers. And to do that, it is necessary to figure out whether or not you can actually see it enough to reduce it properly. And that’s what the next chapter is about.

- Have you ever wondered why people say "Pay Attention"? It's because attention is a finite resource and it is worth something. When you use it, you are actually paying the person or thing with something you have only a finite amount of... ↵

- Okay, so there are two prisoners, so it probably should be The Prisoners' Dilemma, but if I typed that purists would undoubtedly shout at me, and anyway, the dilemma is that of Chuck, or Eve, who are singular, if you see what I mean. ↵

- (I knew these drawings would come in handy) ↵

- Alex Trebek, in memoriam. ↵

- It may appear at this point as if I am 'against' Game Theory in some way. Nothing could be farther from the truth. A healthy amount of scepticism is not always a bad thing. Do your research, properly. Having undoubtedly upset some people I move on. ↵

- So, another peace researcher, like Morton Deutsch. Maybe there is something to thinking about peace, after all...? ↵

- Dawkins, R., The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1976. ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7 ↵

- See also System Trust. ↵

- See also here. ↵

- I say reduced, but I mean 'moulded.' ↵