Pioneers

Introduction

In any field of research there are people who have helped us to change the way we think about a topic. Trust, despite being a field of study that is centuries old, is no exception. This chapter explores the thinking of some of these trust pioneers. Of necessity it’s a somewhat subjective, personal choice of material. That’s how research works, particularly in fields like this. There is an immense amount of literature revolving around trust, much of it recent. For instance, the Social Science Citation Index lists more than 46,000 articles on the subject of trust in the past 25 years or so. To put that into perspective, only around 4,500 were published in the previous 1,000 years. That’s just the social sciences.

The result is that you tend to, if not pick and choose, at least get excited about certain writings. That they fit your own narrative is inevitable–they, after all, pretty much shape it. Note this: different researchers in a field such as this will have different thoughts about it. That is quite healthy: it would be quite a boring world if everyone agreed on everything. My own take on the research that is important is in this chapter specifically and in this book in general. There will be people who think I have missed certain authors or seminal papers or whatever. That’s okay. For one thing, I can’t possibly synthesize 46,000 papers, and nor would I want to. For another, the point of being a so-called expert is that you get to curate stuff in much the same way as a museum curator shows you the things that they think are important from the vastly larger collection the museum may have. It’s a fun part of the job.

Bear in mind, important doesn’t necessarily mean right. In this book I aim show a few different viewpoints from different researchers and thinkers. Sometimes I’ll show why I think these are ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ but often I won’t: the things I present are important to me regardless of their correctness. Your own practice will ultimately determine the rightness of them. That’s part of the joy of doing the research!

This is a book about trust systems and computational trust. It’s not, specifically, a book about trust in human beings, but it is informed by the phenomenon of trust in human beings. So it works like this: I show some of the important work that explores trust in humans which helps to inform the field of computational trust. I’ll show how and why this is the case. I will also, in this chapter and throughout the book, show several different views of how trust in human and computational systems works. Guess what? One such viewpoint is my own (that’s also part of the joy of research: you get to think about and create your own stuff and, if you’re really lucky, change the way people think).

This chapter is titled Pioneers. As such, it will explore the people and research that excites, bothers, informs and moves the field forward. I’ll do it person by person because to a large extent the difference in our thinking were shaped by these individuals as they have presented their work. This is often true of many fields. Take a look back at physics, for instance. Copernicus and Galileo for their solar system and telescopes; Newton and his apple and his three laws (amongst other things!); Einstein and his theory of relativity. Or perhaps Ampére, Ohm, Faraday and Watt. The point isn’t just that they (in some cases) made individual strides forward for the fields they were in. The point is that they took what others had done and moved the world forward in its understanding. Could it have been different people? Sure. Of course in some sense they were the right minds at the right time. But they were the right minds, which is why when we talk about physics in all its guises, their names always come up. Science is like that. The field of the study of trust is not any different.

So who are the pioneers of trust? Read on and find out! For different reasons, the writers and researchers I talk about in this chapter have had an important impact on the field of trust as it relates to trust systems. In many cases the impact has been far-reaching across the study of trust as a whole. For the interested reader (and I hope you are), there is a comprehensive further reading section toward the end of this book. Since the book is electronic rather than paper (but do feel free to print it!) that section and the chapter as a whole will continue to evolve, so do jump in.

Trust Systems Pioneers

Morton Deutsch

Morton Deutsch was a pioneer of peace studies and conflict resolution. It goes without saying then that he would have studied trust. After all, given what we as humans perceive trust to be, it would hardly be possible to have peace of some form or other without trust. In fact, Deutsch was foremost in the study of trust as some form of a computational phenomenon. His definition of an individual focusing on trust, which is foundational, is:

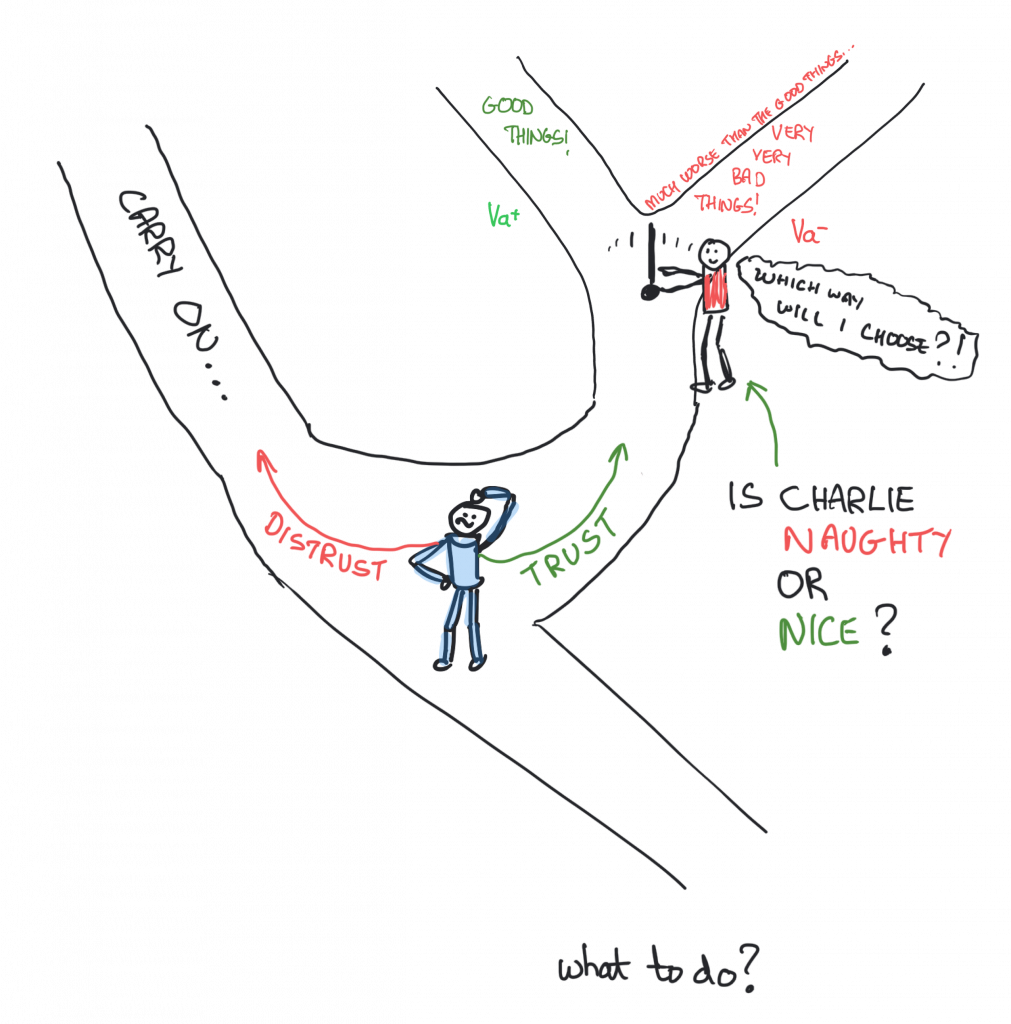

“(a) the individual is confronted with an ambiguous path, a path that can lead to an event perceived to be beneficial (Va+) or to an event perceived to be harmful (Va−);

(b) he perceives that the occurrence of Va+ or Va− is contingent on the behaviour of another person; and

(c) he perceives the strength of Va− to be greater than the strength of Va+.

If he chooses to take an ambiguous path with such properties, I shall say he makes a trusting choice; if he chooses not to take the path, he makes a distrustful choice.” (Deutsch, 1962, page 303)

“Well, sure,” you’re saying to yourself, “but what does that actually mean?” Perhaps it’s easier to see in a picture. Which is good, because I drew one.

To begin, it’s important to tell a story. It’s one that Deutsch himself used (Deutsch, 1973) to make things a little clearer, as well as to discuss things like confidence. We’ll come to confidence, but let’s hear the story first. Stories are good. I’ve taken the liberty of bringing this one into the 21st Century because I can. And because it matters that everyone feels valued. So it’s an adaptation of The Lady or the Tiger.

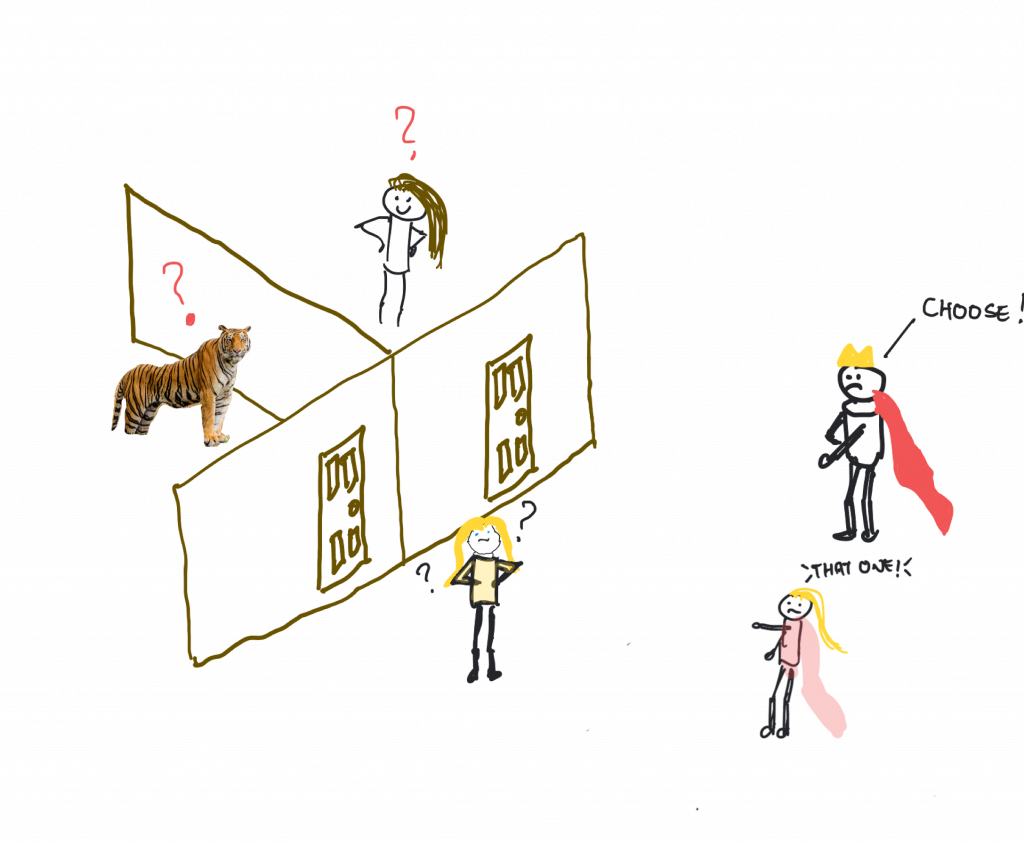

Okay, so there’s this princess. Princesses are fine. This one, let’s call her Alice (see, I knew those characters would come up!). Anyway, Alice falls in love with a beautiful but poor writer in the local town, whose name is Carol. Carol and Alice have an unfortunately brief partnership because Alice’s father, King Bob, finds out about it and is less than pleased. Perhaps not for the reasons you think, after all this is the 21st Century and even kings move with the times. Bob is stuck somewhere around 1970 but for royalty fifty-odd years out of date is pretty hip. In fact, Bob just wants to be able to choose Alice’s life partner himself – alliances are made in such a manner and the blood can’t be diluted etc., etc. (Okay, maybe he’s stuck in 1870).

Here’s where the picture I promised comes in. You can see it on this page. King Bob has poor Carol arrested and brought before him. With a distraught Alice standing next to him he has Carol taken to face two identical doors.

Bob goes on to inform Carol, in suitably kingly tones, that behind one door there is a beautiful someone, who (it is assumed) will steal her heart. Whatever. Anyway, behind the other door there is a tiger. You know, the roaring kind, which almost certainly means almost certain death for Carol (perhaps he’s stuck in 1570). What to do?

Well, Carol is about to make a choice when she notices Alice pointing subtly toward one of the doors. What would you do if you were Carol? (No, not be captured in the first place is definitely not an option.)

Carol chooses that door instantly and steps through to… well, that’s where the story ends. Make your own choice. But that’s precisely the point, you see: you get to make your own choice. If you think back to Deutsch’s definition of trust you’ll remember a few things.

First, there’s the ambiguous path that can lead to a beneficial or a not so beneficial outcome. I’d say we have that situation here. The choice faced by Carol is one that leads to good (technically – I mean, the beautiful lady may not be Alice but at least Carol is alive) or bad (definitely – well, on the assumption that being eaten by a tiger is bad.)

Second, the “occurrence of” the good or the bad is dependent on the actions of another person, who is not under Carol’s control. We’ve definitely got that. After all, Alice is pointing at a door, Carol has no way of making Alice choose one or the other, it just is what it is and it’s Alice’s choice.

Third, the bad has to be worse than the good. We’ll come back to this because it’s important where trust is concerned. In this story, well, as I said above, being eaten is probably seen as worse than not.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The choice to go through a specific door is Carol’s, not Alice’s. So whilst Alice may choose a specific door, Carol is under no obligation to head through it. She chooses to. So, Deutsch’s final condition is met because in the story, Carol chooses to go through the door that Alice points to.

In other words, from Deutsch’s definition, Carol trusts Alice to have made the “right” decision for her. We’ll come back to the reasoning in a bit, but before we do there’s one more important thing to notice in the definition. It’s that Deutsch uses the word perceives a lot. What does this say about trust? That’s right! It’s an individual’s choice based on what the individual subjectively sees in the situation. Trust is subjective. It’s something that is for us to give. This is a vital thing to understand where trust is concerned. It is entirely possible for someone to ask you to “trust me” or “trust the police” or whatever may be. It is entirely wrong for them to demand that you trust them, the police, politicians, and so on. Because trust is a personal choice. You are the one that chooses to trust, based on, well, we’ll see.

Why does this matter? Quite apart from the obvious that I already mentioned (police, politicians, etc.) it matters greatly in situations where people talk about making ‘users’ trust AI (Artificial Intelligence). Nobody can make you trust anything, let alone AI. The choice is yours. No-one can design an AI you will automatically trust because you must. The only thing that can be done is to design systems that are worthy of your trust in some way. Trustworthiness is something separate from but related to trust in very interesting ways. We will get to those in this book and undoubtedly take the time to reinforce this important fact: trust is something you give.

Let’s get back to our tiger, who is either now very hungry or very full of Carol. You’ll remember that I asked the question, why does Carol choose the door Alice points to at all? We’ve kind of established that Carol makes a trusting choice – that Alice will do the ‘right’ thing for Carol, Alice or both. The thought process might be difficult but the choice is clear: choose the door Alice points at. In his 1973 book, Deutsch explores several different reasons why Carol would make the choice, all of them related to a specific kind of trusting action (see also Golembiewski and McConkie, 1975). Without spoiling the fun, think about the negative bits of trust. Sometimes all that trust is, is the best of two bad choices.

Maybe that did spoil it a little, but there we are. Deutsch examines the choice in detail, and so should we. In fact, the decision may have been influenced by entirely different kinds of trust. That they are different raises a very important point about trust – trust is different in different contexts. In this case Deutsch suggests there may be at least nine different (reasons behind) the trust choices made. So, let’s see.

First, and perhaps, hopefully, least, is trust as despair. Sadly, this is something most of us have experienced: that the act of choosing is better than the situation we are in right now (for Carol, it’s the purgatory of both not being with Alice and indeed not knowing if Alice meant her to get eaten or not –which might well have ramifications for their relationship).

The second is trust as social conformity. In many situations, trust is expected, and violations lead to severe sanctions. And so, Carol chooses the door because she may end up socially ostracised or labelled a coward.

The third is trust as innocence. The choice of a course of action may be made upon little understanding of the dangers inherent in the choice. This innocence may be rooted in lack of information, cognitive immaturity, or cognitive defect (so-called pathological trust).

The fourth is trust as impulsiveness. Inappropriate weight may be given to the future consequences of a trusting choice. As we’ll see in our Prisoners chapter, this is a bit like the shadow of the future that Axelrod talks about in his work (for example, Axelrod, 1984). It is also exhibited in the decision of many children to choose one marshmallow now instead of two later.

Fifth, we have trust as virtue. Here, trust is naturally considered a virtue in social life. By now, hopefully, we have reach an understanding that trust is important to society (and it working!) and so, to be sure, it is virtuous. How does this relate to Carol? It’s like this: she trusts Alice because it’s a good thing to do, and not trusting Alice would be, well, wrong. I know, I know, her life is at stake, and so on, but read on, because…

The sixth is trust as masochism. Here, Carol opens the door because she expects (or wants) the tiger rather than the beautiful other, since pain and unfulfilled trust may be preferable to pleasure. Sure, it’s a thing.

Seventh, we have trust as faith. Carol may have faith in ‘the gods’ such that she has no doubt that whatever awaits is fated and thus to be welcomed. As Deutsch notes, and what is more, this chapter explores a little in some way, having faith to a large extent removes the negative consequences of a trusting decision.

Eighth, we have trust as risk-taking or gambling. Carol (faithless Carol) jumps because the benefits of the beautiful other are so much more than the risk of the tiger that it’s worth risking.

Lastly, ninth we have what most people see trust as — trust as confidence. Here, Carol chooses because she has confidence that she will find what is desired rather than what is feared. Cast your mind back a little to the way we discussed trust earlier in this book: it has to do with risk. And so, to make a trusting decision, first we have to accept that there is a risk involved. This story is the very definition of such a situation.

I put it another way toward the start of the book: trust is the response to a situation of risk — it’s one way we manage such situations. It’s also optimistic in the confidence sense. Trust is “strongly linked to confidence in, and overall optimism about, desirable events taking place” (Golembiewski & McConkie, 1975, page 133). The truster always hopes for good things, whilst taking a risk that bad things will happen (Boon & Holmes, 1985).

If you revisit Deutsch’s definition above you’ll notice that the bad things is required to make the situation worse than the good thing would make it better. Deutsch isn’t the only person to think such a thing. As we’ll see, Luhmann defines trust much the same way. It makes sense, too. Think, for example, of a couple who want to go out for a movie together. They get a babysitter for their baby so that they can have some ‘them’ time and off they go. They are clearly expecting the babysitter to look after the baby so that they can get a small reward of a few hours together. This is trust — the cost of the baby not being looked after are incalculably worse than the benefits to be gained from a few hours of peace.

This requirement is not always present in researchers’ definitions of trust, but it is seen as important in many cases. Deutsch goes a little further with some basic assumptions about people. Put simply, that they tend to try to do things that they think will be good for them and not to do things that they think won’t be. The strength of these ‘trying’ actions is related to things like perceived utility (we’ll get to this in a second); whether they think their actions are more likely to make something good happen, or more likely to make something bad not happen; the probability of the good or bad thing happening; the utility they can get from doing the things and the ‘immediacy’ of the event happening (how close are we to the good or bad thing happening). What does that all mean? Think about a situation where you eat a marshmallow and lose a year of your life as a result. Now, losing a year of your life at the age of five is not that ‘immediate’ and so the marshmallow (which has a positive utility–it tastes good!) Is probably going to disappear pretty quickly. But what if you’re 60, 70, 80? You may be less willing to risk losing that extra year and so, well, the marshmallow can wait for the grandchildren to come around. To be even more basic: people are likely to act in a way that helps them to survive.

Deutsch goes a bit further and says that people are actually all ‘psychological theorists’–not only do they do this stuff for themselves, they also think about how others might be doing it and make assumptions (that people will act to survive, get nice things but not at any cost, and so on).

Actually that last bit is interesting not only because it is almost certainly true and helps us to understand the actions of others. It’s also interesting because of one of the problems of doing research on trust: there are an awful lot of definitions of trust. We are all, in our own ways, experts in what trust is. How could we be otherwise? I often start talks about trust by saying that there’s probably a different personal definition of trust for everyone in the room. It’s not too much of an exaggeration either. Remember at the start of this chapter I mentioned the massive number of articles written about trust. This is a part of the reason why.

Okay, so utility. Put simply it’s a measure of what you get out of a situation. Dive a little deeper and you could say that it is the difference between the good bits and the bad bits of the situation. You might measure it with money in some circumstances. For example, you pay the babysitter and you pay for the movie when you go out. It costs you something (forget the trust bit for a second). What do you gain? The pleasure of the movie, the pleasure of being with your significant other for a few hours without interruptions. Are the costs worth the gain? That’s the utility bit. Yes, you can take it much further (we will in our Prisoners chapter) but it’s kind of like this: you gain something and you lose something in most situations. If there is a risk of losing something much more important to you than what you stand to gain, and you can’t control the situation, you put something in place to make that situation bearable.

That something is trust.

This is pretty much where we are with Deutsch at the moment, but consider this: people are not rational and, whilst they do try to maximize the good stuff they’re actually not that good at figuring out what the potential costs are — you might say we’re pretty poor at risk evaluation — and even if we could do it well, putting our baby in the hands of a (potentially very young) stranger is sheer madness. What is the difference between leaving the stranger in your home with the baby and giving the baby to a stranger on the street to look after while you popped into the shops? That we do it (the former not the latter) is evidence of how irrational trust actually is.

Still, we manage to make it work and we can justify it quite well to ourselves. As an exercise, try asking someone to explain why they trusted another person in some circumstance. The further into the rabbit hole of trust you take them, the more defensive they are likely to become. Why? Because trust isn’t rational.

Does this mean that we can trust machines? We’ll see.

Niklas Luhmann

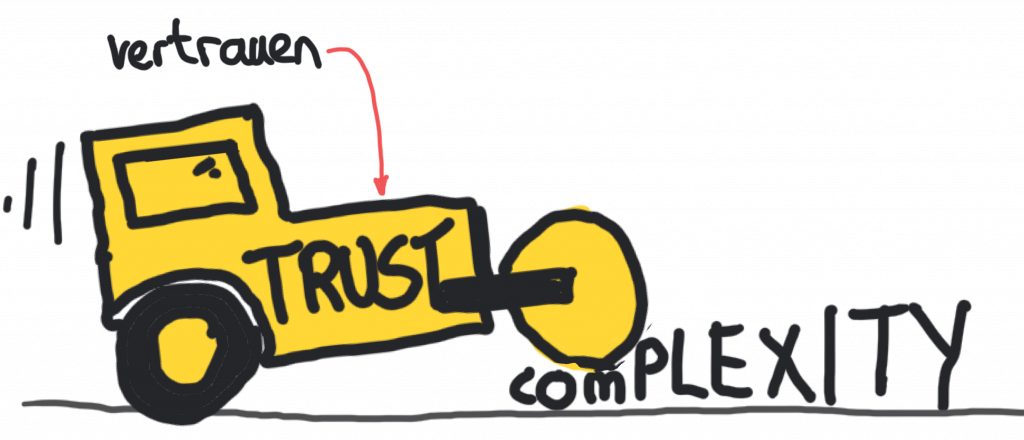

Niklas Luhmann was a sociologist who wrote prolifically about subjects as seemingly disparate as intimacy and the law. His social theory is a little too complex to go deeply into here, and undoubtedly theoretical sociologists would be quite unhappy with me trying to anyway. This, of course, is not to mention how they might feel about what I’m going to talk about anyway, which is Luhmann’s theory as it relates to trust. Luhmann wrote about trust (vertauen) and power (macht) in separate but connected volumes in German. These volumes were brought together in an English translation in 1979 (oddly enough called Trust and Power).

The trust part of Luhmann’s work is what I’ll focus on here. It has the added benefit of being to the point in the English version. Apparently Luhmann’s writings in German were a little complicated. It is at this point that my limited grasp of German would fail, in other words.

For Luhmann, an awful lot of what his eventually systems theory of society would look at was that a social system (a society, if you like) was sort of a zone of non-complexity. It allows the individuals inside it to exist in an infinitely complex external environment because they get to choose what to communicate and pay attention to, and society is constructed of these communications.

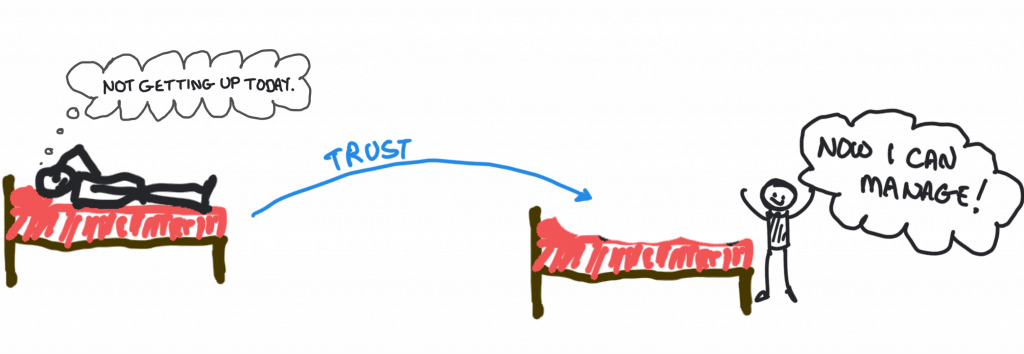

Okay, that was almost certainly not what he would have said at all, but it’ll do for now because as far as trust is concerned, this is exactly what was meant. Trust, for Luhmann, was a means of reducing the complexity of life. Indeed, without it we would have trouble getting up in the morning.

How does that work? You can think of it in a relatively simple way. When you cross the road, you’re implicitly trusting the driver around you not to drive over you. You are implicitly trusting the people around you not to do something bad. You are trusting, in other words, that the society around you will ‘behave’ so that you can continue to go about your own business. Think about this for a second. If you had to think about all the bad things that could possibly happen in your day, how would you feel? Honestly, if you thought about everything, good or bad, you would probably blow your mind. I’m sure I would.

Trust means we don’t have to think about all of those things. It means that we can take some things as given. To put that another way, we can take some things ‘on trust’. We don’t have to think about those car drivers because we can ‘trust’ they won’t try to run us over. When we look at it like that, we can see exactly how trust reduces complexity in everyday life. This was Luhmann’s point, of course. Naturally there is much more. In particular, Luhmann sees trust as a “basic fact of human life” (Luhmann, 1979, page 4).

It’s actually a really powerful theory because it explicitly acknowledges a few different things:

- The fact that human beings live in a complex society

- The fact that human beings can’t really control other human beings (not really, and this is where that power bit comes in, although we won’t go there right now).

- The fact that human beings can therefore make life much more complex of themselves and others because of this agency.

If that all seems a little complicated, think of it like this. We all wander around doing our own thing. Much of the time us doing that has no effect on other people, but sometimes it does. Sometimes people might need us to do something. Sometimes us doing something gets in the way of what others might wasn’t to be able to do. And so on. Because of this, we have the means to make things more complicated for ourselves and others simply because of the things we can do. Not only that, because if we do trust people, or even take things on trust, like we talked about earlier, this vastly increases the things that we can in fact do. We can cross the road to look at what is on the other side. We can hire a babysitter, and so on. As Luhmann said:

“Where there is trust there are increased possibilities for experience and action, there is an increase in the complexity of the social system and also in the number of possibilities which can be reconciled with its structure, because trust constitutes a more effective form than, for example, utility theory of complexity reduction.”

(Luhmann, 1979, page 8).

Pretty powerful stuff, that–not only does trust allow us to do more and new things, it allows us to handle these new things at the same time. One more way of looking at it? Trust is a way of coping with the freedom of others (Luhmann, 1979).

What was that about utility theory? It’s like this: in utility theory people, as rational actors, as supposed to act to maintain or increase utility–we’ll pick the path which has the best reward (or lowest cost) and so on. That sounds great until you realize that really, we’re not very rational at all and in fact we do some rather silly things.

The point Luhmann was making there is that trust isn’t an entirely rational thing. But that’s okay because it allows us to do things which utility theory might say were stupid (or wrong). Like, for instance, jump off a bridge with an elastic cord tied around our ankles.

In other words, trust allows us to accept the fact that risk exists. We’ll come back to this a lot more in the course of the book, because trust and risk are beautifully intertwined. For Luhmann, as for Deutsch if you think about it, trust is needed because risk is there. As Luhmann put it, “Trust . . . presupposes a situation of risk” (Luhmann, 1979, p.97).

Now we are getting somewhere, you think to yourself. Sure. Look at it like this: we know that risk is there is pretty much everything we do, right? There’s a risk the babysitter might not be a nice person. There’s a risk the person we elect might be a sociopath (more on that one later). There’s a risk that the person controlling a huge social network is a sociopath, come to that. There’s a risk that Steve might fail to finish this book. Put it another way: making plans means looking at the risk that in the future stuff might happen that makes the plans screw up: “a knowledge of risk and its implications allows us to make plans for the future which take the risks into account, and thus make extensions to those plans which should succeed in the face of problems or perhaps unforeseen events” (Marsh, 1994, page 42).

Sounds good, right? A quick look back at Deutsch will show you something a little similar. Carol chooses the door she does despite the risk of being eaten. The truster, in this sense, hopes for an outcome that is good, but accepts the risk that it might turn out, erm, badly (Boon & Holmes, 1991).

This view is not unusual. Piotr Cofta (2007) also looks at how risk and trust, as well as control, are related, as we’ll see later.

Diego Gambetta

Gambetta, another (and another of our pioneers) who has studied trust extensively, defines trust like this in his book:

“Trust (or, symmetrically, distrust) is a particular level of the with which an agent assesses that another agent or group of agents will perform a particular action, both before he can monitor such action (or independently of his capacity ever to be able to monitor it) and in a context in which it affects his own action.”

(Gambetta, 1990, page 217).

Clearly this has a lot in common with Luhmann, especially the last bit — trust is a way of coping with the freedom of others. It also brings in the idea of subjective probability, which is quite important, especially when we start talking about how to compute trust, but bear in mind that trust is not probabilistic. It’s also important that Gambetta talks about using values for trust, again because computers like that sort of thing.

You may have spotted that Gambetta refers to distrust in this definition. Specifically, he talks about distrust being symmetrical to trust. It’s not entirely clear what that means, and I’m not sure it’s correct, but we’ll get to distrust and things like that later in the book. It is worth bearing in mind though that trust and distrust are not two sides of the same coin. As Luhmann notes, they are not merely opposites, they are functional equivalents. You can have trust where distrust has been, and vice versa.

Gambetta’s work is interesting, and not just because he studies the mafia. One of the things he talks about is signs (Bacharach & Gambetta, 2001). Basically this is about the signs we give about how trustworthy in a given situation we might be. These are things like businesspeople wearing business attire, or police officers wearing their uniform. The signs can be more or less overt than that, and the basic assumption for this is of course that the person who is about to make a trusting decision has eyes. To put it another way, “the truster sees or otherwise observes the trustee before deciding. She therefore can, and should, use these observations as evidence that the trustee has, or lacks, trustworthy-making qualities” (Bacharach & Gambetta, 2001, page 148). Now this is interesting not just because the signs are acknowledged, but that the word trustworthy is used. It’s an important word and we’ll discuss it in detail later, but for now remember: trust and trustworthiness are not the same thing.

As I will repeat through the book, Trust is something that you give, Trustworthiness is something that you have. To put it another way, I’m quite free to trust an untrustworthy person…

So far, we’ve seen that people have defined trust in terms of risk, and in terms of the freedom of others. But what if we look at it from the point of view of how people might behave in a society where they are perceived to be, say, experts in some field or other? This is related in part to what we were just talking about with trustworthiness. Surely you would be more likely to want to trust a car mechanic to fix your car than a computer scientist? I can fix cars, but I’m really not very good at it. The end result is not a great job and it takes ten times as long, I’m afraid. On the other hand, whilst I have the greatest of respect for mechanics, I wouldn’t necessarily ask them to fly a passenger jumbo jet across the Atlantic.

Bernard Barber

Do you see where this is going? Bernard Barber did. He’s another of our pioneers. He’s another sociologist who studied trust. He actually started to look at it because he was a little dissatisfied with how trust was referred to in everyday life. I can’t say I blame him. Things have not got any better. Trust is probably one of the most overloaded words out there in the English language. Sometimes we even use it in the exact opposite way that it should be used. But we’ll come to that when we talk about security. Let’s return to Barber. In his The Logic and Limits of Trust (Barber, 1983) he attacks the problem in various ways. As a sociologist he sees trust as an aspect of all social relationships, and “predominantly as a phenomenon of social structural and cultural variables and not . . . as a function of individual personality variables” (Barber, 1983, page 5). That last bit puts him squarely in Luhmann’s camp, by the way, and not Deutsch’s. That’s definitely okay. And it’s not just there either because Barber sees trust as a way of looking at the future. An expectation. Barber specifically lists three types of expectations in these social relationships (Barber, 1983, page 9, from Marsh, 1994, page 44)

There are many reasons why this is important. Firstly, because there is an explicit reference to natural as well moral social orders. Part of this is an expectation that things like physics and biology stay the way they are. This is actually a really neat thing because all of a sudden we can say things like “I trust this chair to hold my weight” and have it mean that I trust the laws of physics will keep on working and I won’t fall through the substance of the chair (which is unlikely to happen but you never know). Barber’s reference to the moral social order is also interesting and akin to the kind of trust that Bok says society will collapse without (Bok, 1978).

Secondly, it’s important because it introduces the idea of competence to us. We trust people because they are technically competent. For instance, when I say I trust the chair it is also likely because I trust that the person who made the chair was competent at making chairs . It’s this kind of trust we place in politicians in the sense that they are good at their jobs, for example.

Third, Barber introduces us to the idea of fiduciary trust. This is a vital part of how our society actually works. Remember that car mechanic? How would I even know if the work they did was dangerous and liable to result in a crash? It’s about responsibility and obligations: the mechanic is obligated to be responsible when fixing my brakes. Think about it from the point of view of a patient in a hospital talking with a surgeon: at some point the surgeon is the expert who will be cutting into the patient and it would be nice if they knew what they were doing, It would also be nice if they were good at what they did. Further, and probably even more importantly, the patient trusts the surgeon to have their best interests at heart when performing their job. That’s fiduciary trust.

It’s interesting, isn’t it? When the year 2020 started few of us even knew about Wuhan, and probably even fewer knew anything much about COVID-19. When it finally appeared in our midst we trusted the professionals (the health-care experts) to have our best interests at heart as a society, and as a result to give the right advice to the politicians (who we elected to have our best interests at heart, at least in some way). We trusted the politicians to listen and do the right thing. And so when the lockdown happened in various parts of the world, people listened.

Where trust in any of those things broke down, the lockdown either simply didn’t happen, to disastrous effect, or its effect was limited by people who perhaps didn’t have the best interests of their constituents at heart. And as I write this in 2021 when we are still facing the problem, our trust in the chain may well be broken in various parts of the world because those we trusted to have our best interests at heart failed that test in some way: perhaps they travelled when they asked us not to; perhaps they didn’t wear masks when we were asked to; perhaps it was other things. The result? If you’re reading this you can probably see it for yourself.

Trust can be a matter of life or death.

It’s the fiduciary trust, allowed with the idea of competence-based trust, that is quite powerful in Barber’s work. It gets even better though because Barber then thinks about the fact that someone who is good at one thing might be rubbish at another. To put it another way, “trust cannot necessarily be generalized.” (Barber, 1983, page 18). As a case in point, I’m actually quite good at writing and I’m not too bad at cooking but, as we will see later, neither of those things say anything about my skills as a brain surgeon.

Onora O’Neill

Trust as non-generalizable is important and something that Dame Onora O’Neill (another of our pioneers!) put quite succinctly in her TEDx Parliament talk in 2013:

My own usual example in this regard is that I would trust my brother to drive me to the airport but not to fly the plane.

The thing is, though, if someone has your best interests at heart, they won’t actually try to do something they know they can’t do because it would let you down. In this sense, we trust people to know their limits and stick within them. There’s much more wrong with saying you can do something that you can’t and failing than there is of saying you don’t know how and asking for help. This of course begs another question: is the person who trusts mistakenly at fault for doing so? Is the person who was trusted mistakenly at fault? I’ll leave you to think about that one for a while.

Importantly and certainly poignant at the time of writing, Barber sees fiduciary trust as important as a social control mechanism in a positive sense. Think about it like this: society would probably like to be peaceful and well run by, say, politicians. The thing is, to run society means that someone has to have power. This power is the politicians’ because they are granted our trust (Dasgupta, 1990). As Barber notes:

“… the granting of trust makes powerful social control possible. On the other hand, the acceptance and fulfillment of this trust forestalls abuses by those to whom power is granted.”

(Barber, 1983, page 20).

The thing is, if we do want to trust the people we put in power, we have to trust that we can remove them from power, through the ballot box preferably, otherwise if necessary (Dasgupta, 1990). As we have sadly seen, the breakdown of this trust is apt to be violent if the ballot box is seen as an inadequate control mechanism (Marsh, 1994, page 46).

Piotr Cofta

Control is one of the main aspects of the work of Piotr Cofta (for example in 2007), yet another of our pioneers. Cofta sees trust and control as diametrically opposed. Let’s see what that means. As we’ve already seen in this chapter and we’ll see much more in the book as we go on, trust is explicitly tied to risk: if risk exists, trust is necessary (Luhmann, 1990). As Dunn says, “however indispensable trust may be as a device for coping with the freedom of others, it is a device with a permanent and built-in possibility off failure.” (Dunn, 1990, page 81). When we trust someone (or something) in some situation to do some thing, we accept that they might not do it. We accept that things can go wrong. We accept risk.

This brings us back to the question I left you with earlier: whose fault is it when trust is betrayed? Still thinking about it? Okay, let’s carry on then.

If it is the case that trust “presupposes… risk” (Luhmann, 1979, page 97), and I certainly believe that it is, where does that leave us with respect to control?

Control means what it says. If you control something, you know from one instant to the next what it will do. How can it be otherwise? So here’s the thing: if you know what will happen, where is the risk?

Exactly.

Cofta’s argument is that we are increasingly relying on technology to connect us, and this has problems if we think about those signs I talked about before – after all, how can you tell who is a dog on the Internet? In his work, Cofta examines the idea of trust and control with respect to our inability to tell if someone is trustworthy at the other end of the line.

There’s more though: part of the problem isn’t that visibility thing, it’s complexity. How does the Internet work? How do mobile communications work? Does anyone have a really solid understanding of the whole of the Internet – where the cables are, where the routers are, how they all work together and where a single piece of information might be at any given time?

Of course it’s a rhetorical question.

More to the point, some people probably do understand all this, but bear this in mind: our general lack of understanding is a definite barrier to our ability to control the systems we use. And if we can’t control the systems we use, what does that leave us? It leaves us with a risk that they might not work the way we want them to. And when there’s a risk, there’s going to be trust.

Another example might help here, so let’s return to my car. Actually, I drive an electric one, so let’s return to the truck I owned previous to the car. There’s a picture of it (Figure 2.8).

In this picture you will notice that the weather is a little inclement. This happens sometimes in Canadian winters. At such times, if I needed to go someplace, there may well have been fingers crossed. You see, the real value I placed in my vehicle is the ability to start when the weather is like that, and the temperature is around –30 or so Celsius. The conversations I have had in the past with my vehicles are often telling. They include cajoling, begging, and more than once, threatening the scrap dealer (needless to say they don’t always work). The thing is, I need my truck to start in all weathers. I trust it it to do that.

Consciously or not, there is an expectation, perhaps based on all the other –30 days, perhaps based on the fact that I plugged in the vehicle overnight, maybe even that I had it serviced regularly, and so on, that the thing will start, and I won’t be left stranded in the cold.

Looked at another way, this is a transactional form of trust In a sense. I give care to be able to trust. The more care I give in the sense of servicing, or plugging in when the weather is going to be cold, etc., the more entitled to not being ‘betrayed’ by the vehicle I might feel. This is related to the transactional trust explored in Reina and Reina’s Trust and Betrayal in the Workplace (Reina & Reina, 1999) where, amongst other things, trust is given in order to maintain trustworthiness (see also Stimson’s quote earlier in this little book). The difference, as others have pointed out, is that the truck doesn’t actually have the capacity to betray me – it’s an inanimate object.

And yet, we still talk about inanimate things as if we trust them. We’ll get to this when we start talking about the Media Equation later in the book.

This quite nicely brings us to my unanswered question though: if your trust is betrayed, whose fault is it? The picture is perhaps building a little more, especially if we bring transactional trust into the picture. The question begins to turn itself around to something like “Do I have the right to trust you to do this thing?”

Let’s leave it there and carry on.

Jeremy Pitt

Of the pioneers here, Pitt is one of the more recent, but his work has left a lasting impression on the field[1], particularly in the how to use social agents to investigate theories. In his extensive work Pitt has examined social justice, Ostrom (see here for Ostrom!), fairness, forgiveness, trust, prisoners dilemmas (if you don’t know what that is, I write about it in the next chapter) and more. He has invented a particular way of looking at these things, which he calls Artificial Social Construction. What, you ask, might this be? Put simply, it’s using artificial agents to create artificial societies in which to test the theories he examines. It’s actually pretty cool when you think about it.

At the heart of this is that many people have lots of ideas about how societies work. For instance, as you’ll find in the next chapter, game theory researchers think in terms of how rational agents behave in specific situations, Ostrom thought about how people come together in resource management contexts, Gambetta uses trust to think about things like cooperation among people in different groups, with different information, and so on. It is not always evident, despite the fact that some of these theories are based on careful observation or experimentation, that they actually might be relevant or useful (or powerful) in other social settings. So, one way to find out is to build one of those social settings and find out what happens. How does one do that? With plenty of coding and plenty of thinking about how to take an abstract theory and make it implementable so that you can encode it into the agents that you want to use the theory.

In turns, Pitt and colleagues have examined trust, forgiveness, justice, fairness, scarcity and much more. His work is far-reaching and his methodology extremely powerful.

I am by no means doing justice to Pitt’s work here. In fact, to do that, you’d need a whole book, so it is indeed fortunate that there is one! There are also extensive publications for you to look at in the further reading section! And to make things even more worthwhile, I was able to interview him and he has given permission to use the result here in this book. To watch it (I highly recommend you do…) head to the website for this book.

We’re about at the end of our pioneers for now. However, the interesting thing about pioneers in a research field is that they’re always popping up. If the research field is living, there will be moments in it where everyone should stand up and take notice. That makes this chapter, perhaps even more than the rest of the book, a living document.

In other words, watch this space.

Meanwhile, it’s time to talk about Prisoners, in what could be another chapter but could as easily just belong in this one. It’s your call.

- And continues to do so ↵