9.6 The Spectrum of Allies

Often, we think that if we could just give someone the right fact, they would instantly change their mind. This, however, is not true. Changing your mind is a hard thing to do, and many people rarely do it. No one likes to admit that they’re wrong. So, sometimes it can help to think about not just delivering a convincing argument, but thinking about how to move someone from one position to another.

In her essay “Making Them An Offer They Can’t Refuse,” Jeanie Wills suggests that if you want to persuade your audience, you shouldn’t just focus on what you want your audience to do, but what you want them to be. She says:

Our words can have an even more profound effect if we consciously offer the audience a clearly defined role to play. When the role is one the audience knows how to accept, then they can become people who are more knowledgeable, who have more intellectual depth, and who have a greater understanding of a subject than they did before. Accepting such a role has a ripple effect. For instance, audiences who have been moved to take on a new role may be more likely to accept other roles that are similar in nature. In other words, the audience learns that they can learn, and they take that knowledge not only into other classes, but also into their professional life. (Wills, 191)

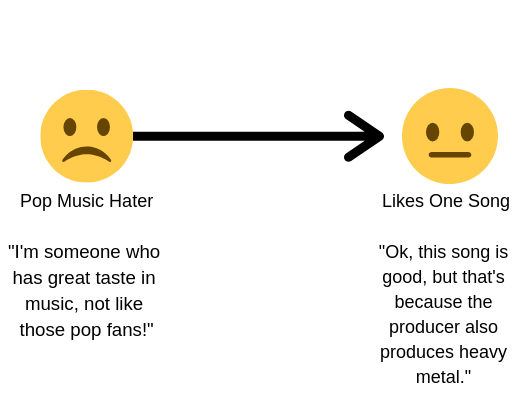

By thinking of persuasion as offering your audience a new role to play, you can see persuasion as an active process. Let’s say that you have a friend named Ahmed who is a heavy metal fan and who considers himself too much of a music snob to listen to pop music. Even the most well-reasoned argument will probably not turn Ahmed into a pop music fan overnight because he’s currently playing the role of Heavy Metal Fan Who Looks Down on Pop. It’s part of his identity.

If you want to convince him to play a new role, you’re going to think about the journey he will take to get there. You’ll also have to lay out the benefits of thinking in a new way. Maybe you convince Ahmed to listen to a pop song that was produced by a well-respected producer or one that a heavy metal artist has recommended. You’re not asking Ahmed to change his worldview, just showing him that liking this one song still allows him to keep his identity as someone with “good taste in music.” That’s not too big of a leap.

If Ahmed enjoys this one song, he’s seen that it’s possible to like at least a little bit of pop music. That doesn’t mean that he’s going to run to the nearest Taylor Swift concert, but it might mean that he would be open to hearing another pop song, or maybe a whole album. Your persuasive strategy has allowed Ahmed to transition from Heavy Metal Fan Who Looks Down on Pop to Fan of A Wide Range of Music, Which Includes a Little Bit of Pop. He’s seen that liking a wide range of music makes him more cultured, not less. He’s also seen that while there’s plenty of bad pop music out there, he held some stereotypical views about pop. He can be a music snob and a fan of some pop songs at the same time.

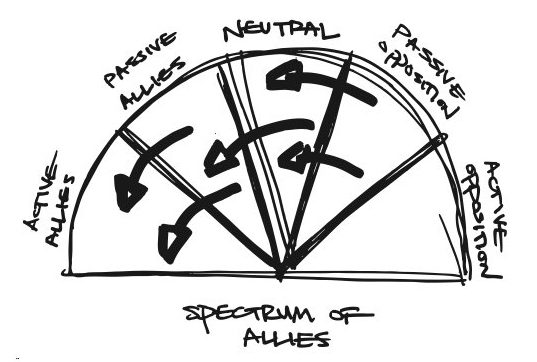

When you begin crafting your persuasive message, it might be helpful to draw a diagram of the role your audience is currently occupying, the role you want them to assume, and the journey you’ll take them on.That’s where the Spectrum of Allies comes in. This is a model that helps activists and community organizers change the public’s opinion on an issue.

Here’s how a spectrum-of-allies analysis works: in each wedge you can place different individuals (be specific: name them!), groups, or institutions. Moving from left to right, identify your active allies: people who agree with you and are fighting alongside you; your passive allies: folks who agree with you but aren’t doing anything about it; neutrals: fence sitters, the unengaged; passive opposition: people who disagree with you but aren’t trying to stop you; and finally your active opposition. Some activist groups only speak or work with those in the first wedge (active allies), building insular, self-referential, marginal subcultures that are incomprehensible to everyone else. Others behave as if everyone is in the last wedge (active opposition), playing out the “story of the righteous few,” acting as if the whole world is against them. Both of these approaches virtually guarantee failure.

For example, in 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a major driver of the civil rights movement in the U.S. South, conducted a “spectrum-of-allies style” analysis. They determined that they had a lot of passive allies who were students in the North: these students were sympathetic, but had no entry point into the movement. They didn’t need to be “educated” or convinced, they needed an invitation to enter. To shift these allies from “passive” to “active,” SNCC sent buses north to bring folks down to participate in the struggle under the banner “Freedom Summer.” Students came in droves, and many were deeply radicalized in the process, witnessing lynching, violent police abuse, and angry white mobs, all simply as a result of black activists trying to vote.Many wrote letters home to their parents, who suddenly had a personal connection to the struggle. This triggered another shift: their families became passive allies, often bringing their workplaces and social networks with them. The students, meanwhile, went back to school in the fall and proceeded to organize their campuses. More shifts. The result: a profound transformation of the political landscape of the U.S. This cascading shift of support, it’s important to emphasize, wasn’t spontaneous; it was part of a deliberate movement strategy that, to this day, carries profound lessons for other movements.

Practice the Spectrum of Allies

Practice the Spectrum of Allies by placing the people below according to what “wedge” they belong in. After you’re done, check your work.

Attribution

“The Spectrum of Allies” from Business Writing For Everyone by Arley Cruthers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.